The Skeletal System

THE SKELETON

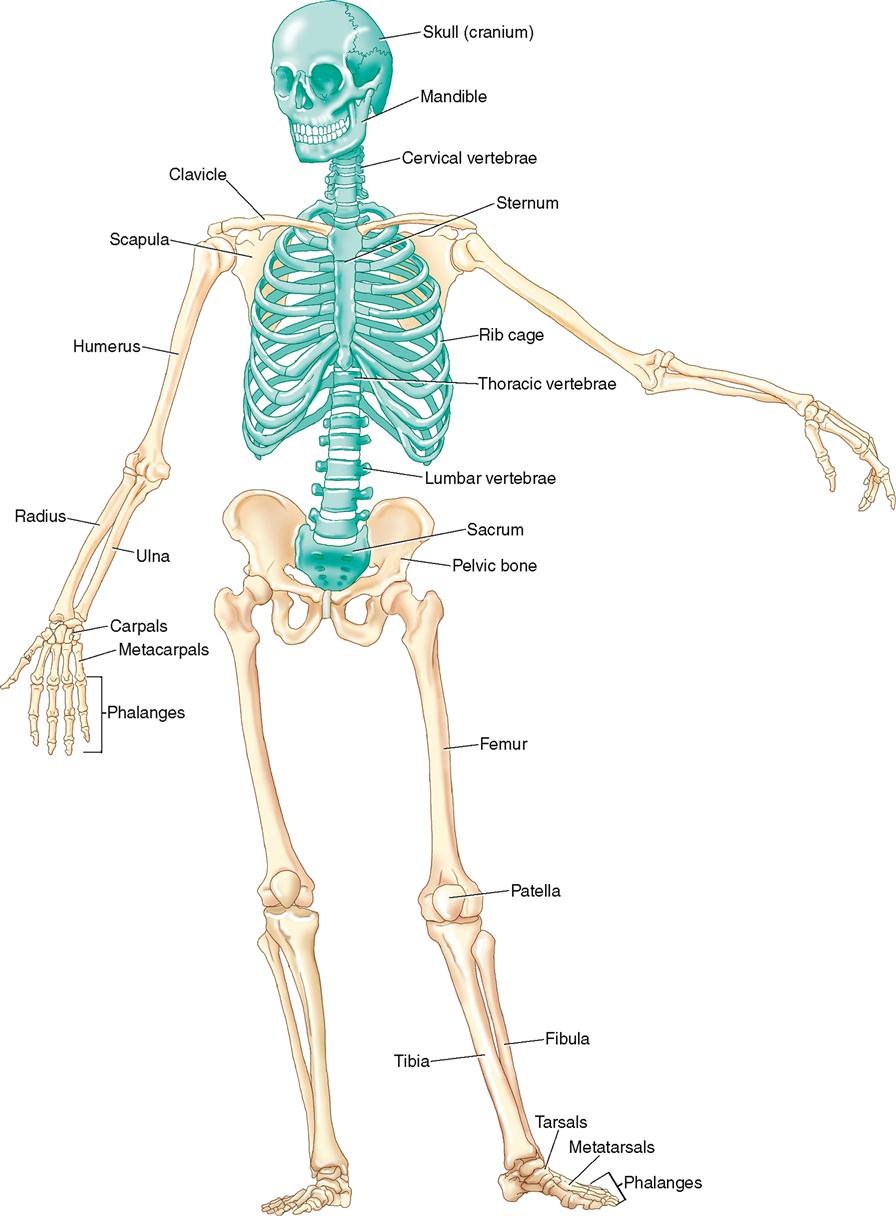

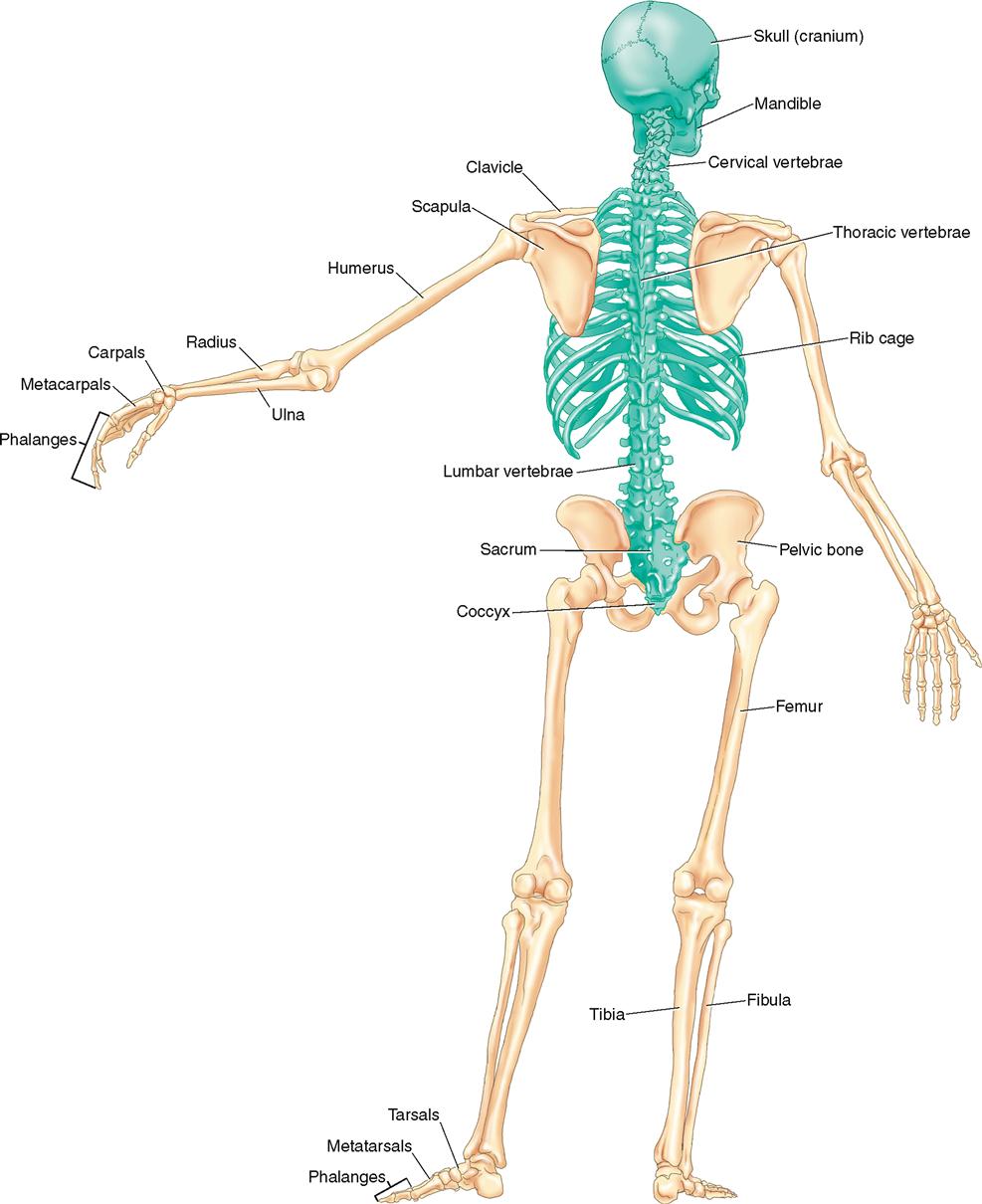

The skeletal system is composed of approximately 206 bones and can be divided into bones of the axial body and bones of the appendicular body. Figure 2-1 is an anterior view of the full skeleton. Figure 2-2 is a posterior view.

JOINTS

Wherever two or more bones come together, in other words, join, a joint is formed.

Structural Classification of Joints

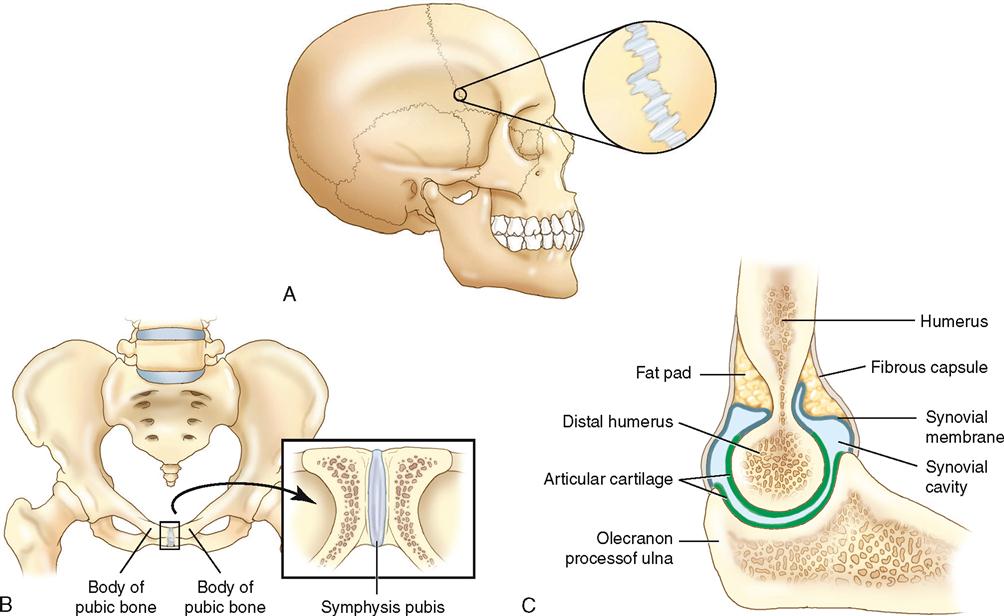

Structurally, the definition of a joint is having the two (or more) bones united by a soft tissue. There are three structural classifications of joints: (1) fibrous, (2) cartilaginous, and (3) synovial (Figure 2-3 on page 44). Fibrous joints are united by dense fibrous fascial tissue, cartilaginous joints are united by fibrocartilage, and synovial joints are united by a thin fibrous capsule that is lined internally by a synovial membrane, enclosing a joint cavity that contains synovial fluid. Only synovial joints possess a joint cavity and have articular cartilage that covers the joint surfaces of the bones.

Functional Classification of Joints

Functionally, a joint is defined by its ability to allow motion between two (or more) bones. There are three functional classifications of joints: (1) synarthrotic, (2) amphiarthrotic, and (3) diarthrotic. Synarthrotic joints permit very little motion; amphiarthrotic joints allow limited-to-moderate motion; and diarthrotic joints allow a great deal of motion.

Generally, a correlation exists between the structural and functional classifications of joints. Fibrous joints are usually classified as synarthrotic because they allow very little motion; cartilaginous joints are usually classified as amphiarthrotic because they allow a limited-to-moderate amount of motion; and synovial joints are usually classified as diarthrotic because they allow a great deal of motion.

Types of Synovial Joints

Diarthrotic synovial joints can be subdivided based on the number of axes around which they permit motion to occur. The four categories are (1) uniaxial, (2) biaxial, (3) triaxial, and (4) nonaxial. These categories can be further subdivided based on the shapes of the bones of the joint.

Uniaxial Joints

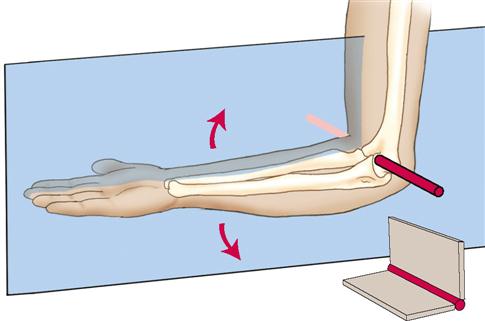

There are two types of synovial uniaxial joints: (1) hinge and (2) pivot. Hinge joints act similar to the hinge of a door. One surface is concave and the other is shaped similar to a spool. Flexion and extension are allowed in the sagittal plane around a mediolateral axis. The humeroulnar (elbow) joint is a classic example of a hinge joint (Figure 2-4 on page 44).

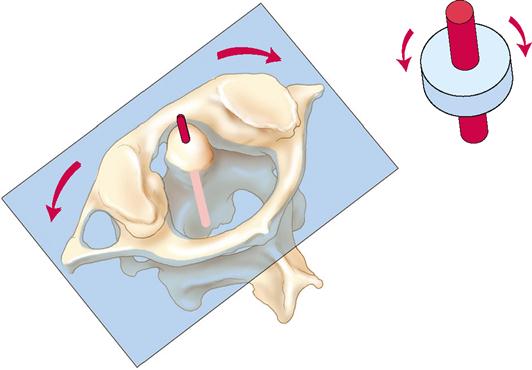

The pivot joint is another type of synovial uniaxial joint. A pivot joint allows only rotation (pivot) motions in the transverse plane around a vertical axis. The atlantoaxial joint of the spine is a classic example of a uniaxial pivot joint (Figure 2-5 on page 45).

Biaxial Joints

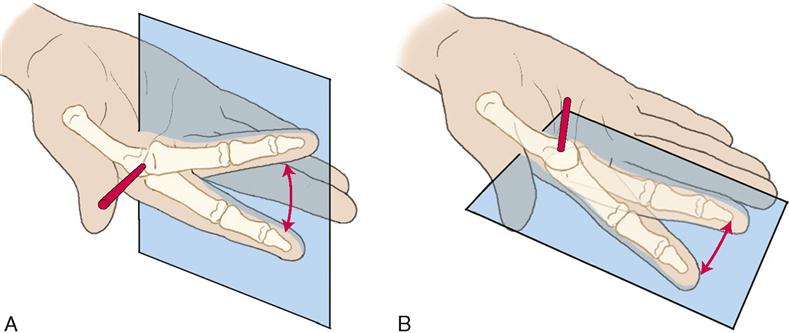

There are two types of synovial biaxial joints: (1) condyloid and (2) saddle. A condyloid joint has one bone whose surface is concave, and the other bone’s surface is convex. The convex surface of one bone fits into the concave surface of the other. Flexion and extension are allowed within the sagittal plane around a mediolateral axis, and abduction and adduction are allowed within the frontal plane around an anteroposterior axis. The metacarpophalangeal joint of the hand is an example of a condyloid joint (Figure 2-6).

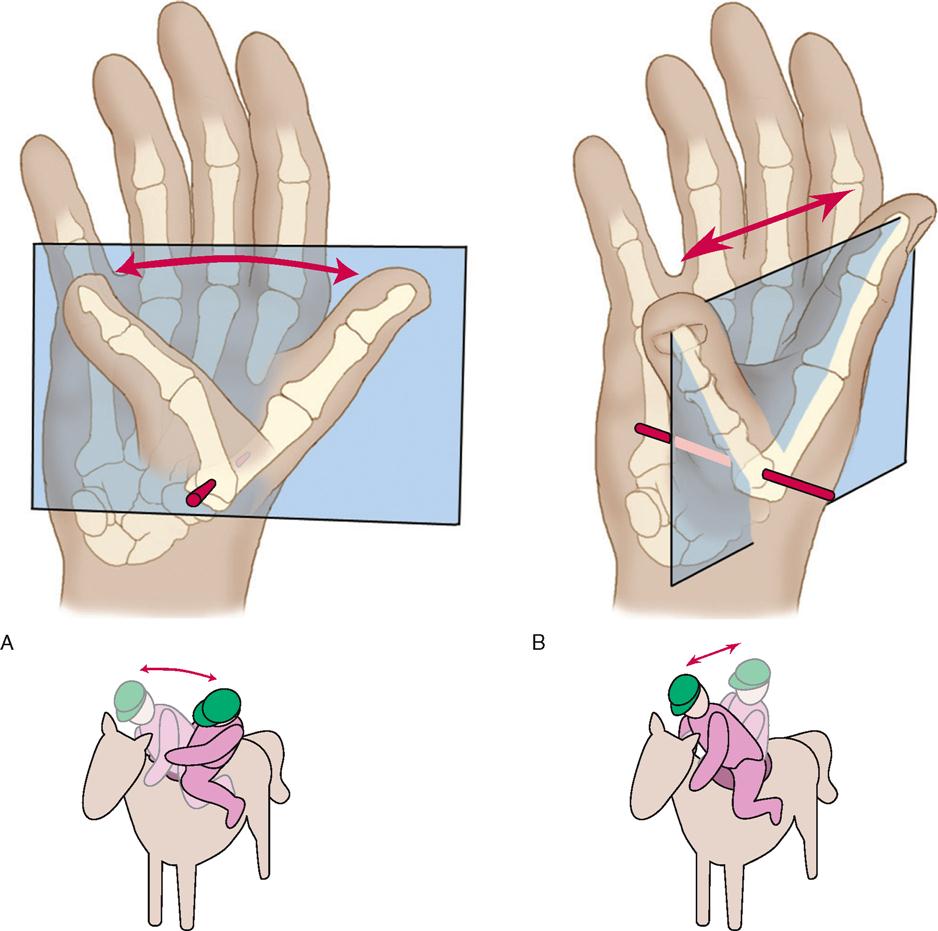

The other type of synovial biaxial joint is the saddle joint. Both bones of a saddle joint have a convex and concave shape. The convexity of one bone fits into the concavity of the other and vice versa. Flexion and extension are allowed in one plane, and abduction and adduction are allowed in a second plane. Interestingly, a saddle joint also allows medial rotation and lateral rotation to occur in the third plane; therefore some might consider a saddle joint to be triaxial. However, because these rotation actions cannot be actively isolated, a saddle joint is still considered to be biaxial. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb is a classic example of a saddle joint (Figure 2-7).

Triaxial Joints

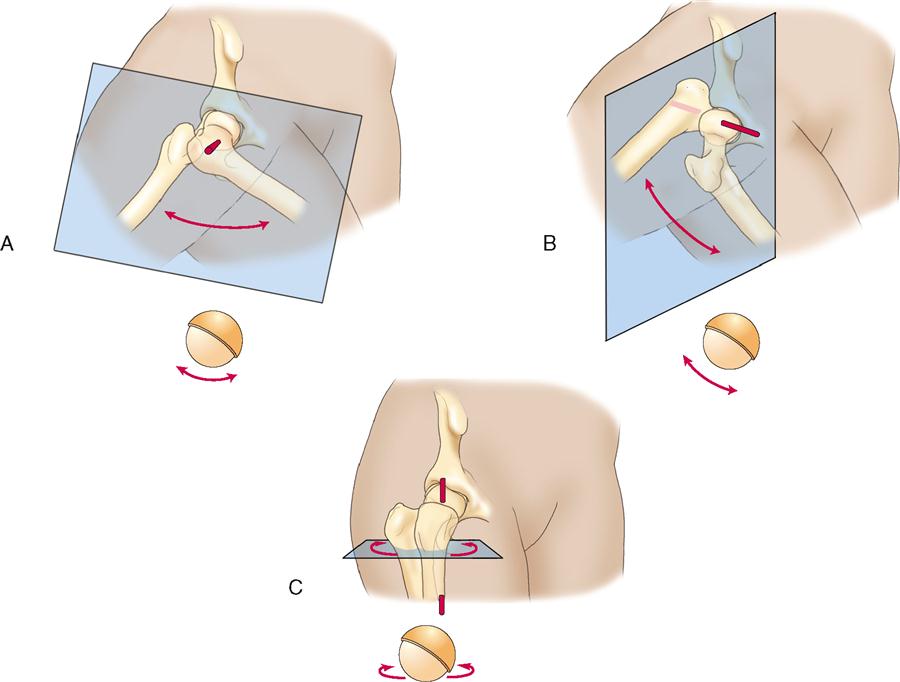

There is only one major type of synovial triaxial joint: ball-and-socket. As its name implies, one bone is shaped like a ball and fits into the socket shape of the other bone. A ball-and-socket joint allows the following motions: flexion and extension in the sagittal plane around a mediolateral axis; abduction and adduction in the frontal plane around an anteroposterior axis; and medial rotation and lateral rotation in the transverse plane around a vertical axis. The hip joint is a classic example of a ball-and-socket joint (Figure 2-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree