Muscles of the Pelvis and Thigh

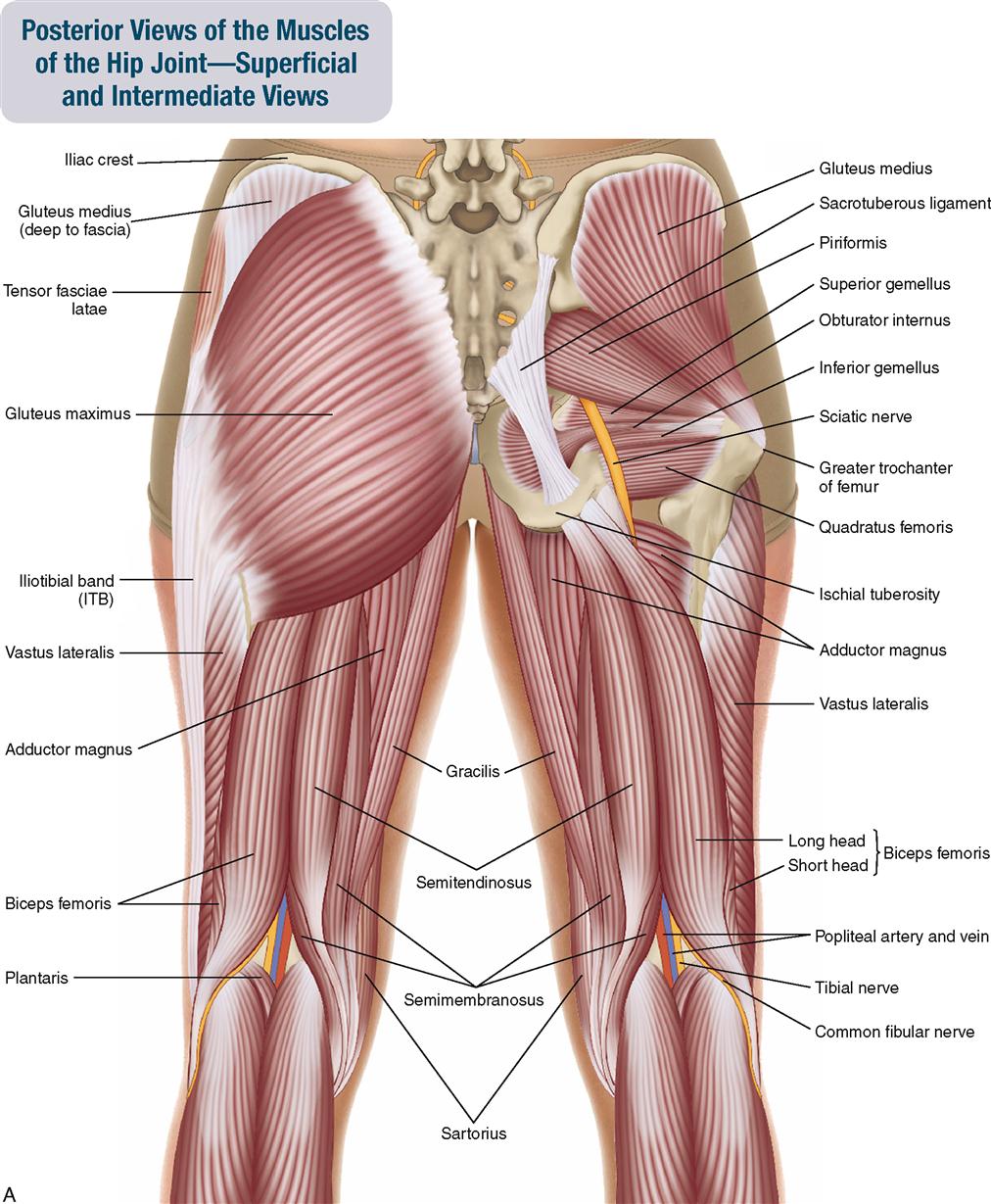

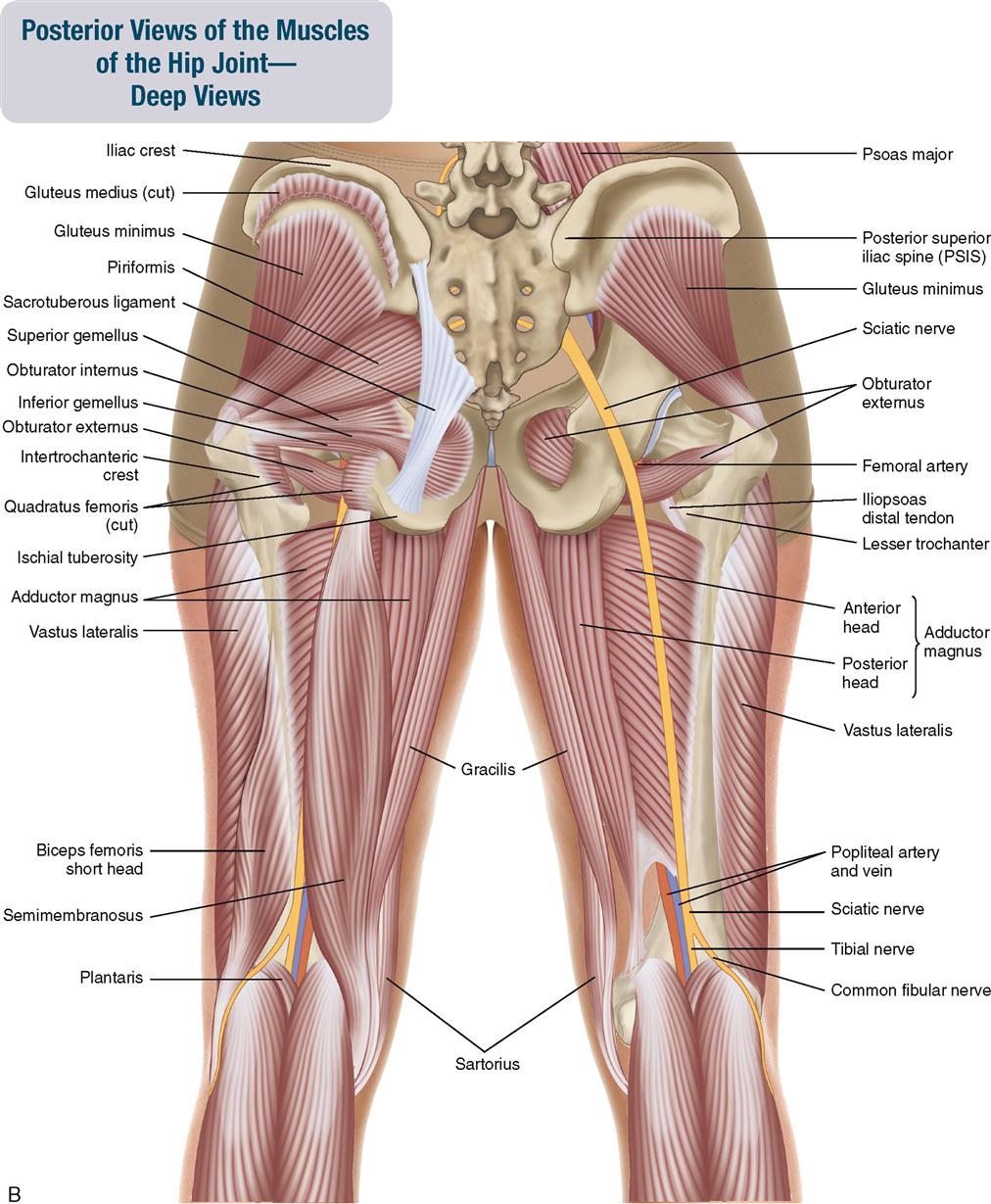

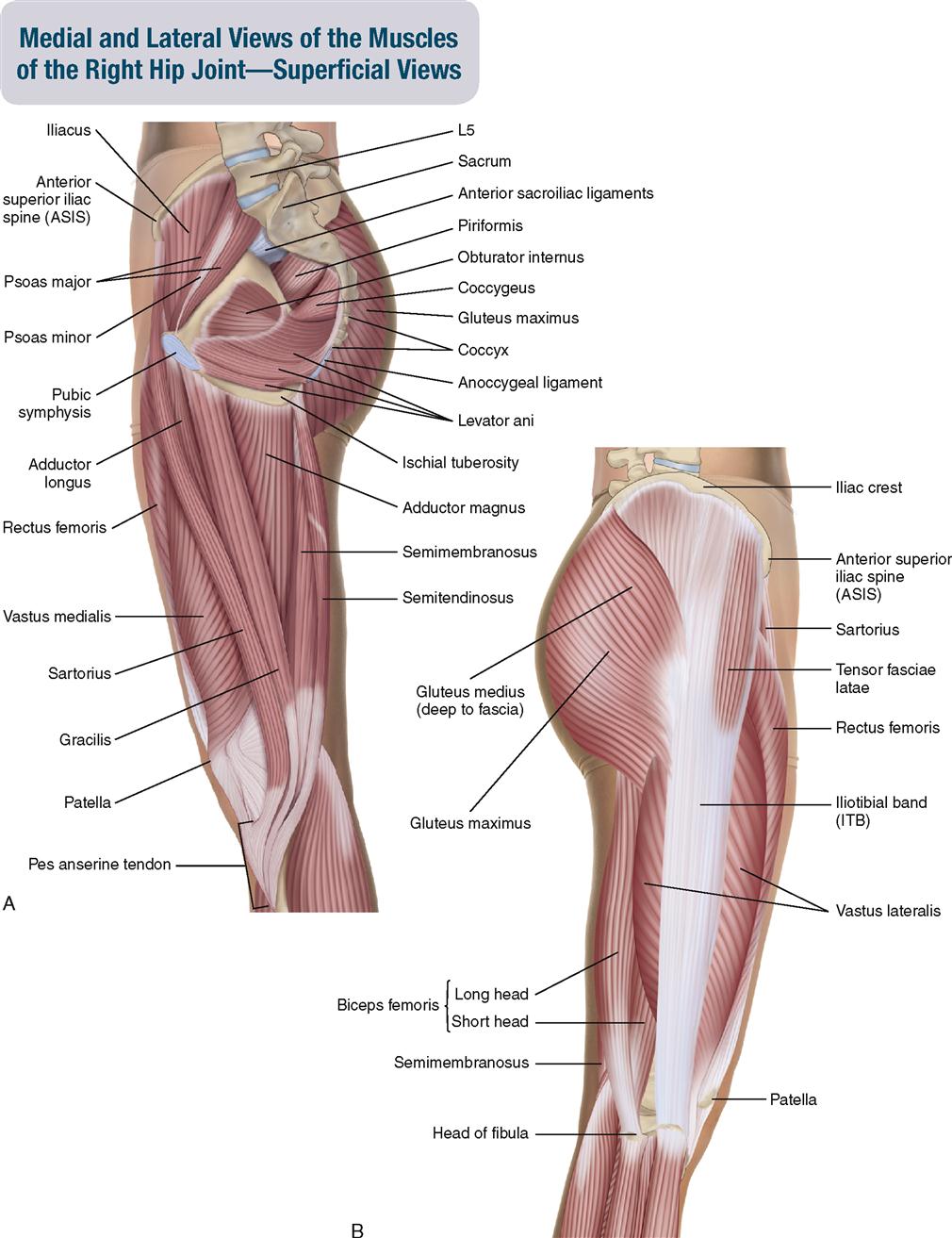

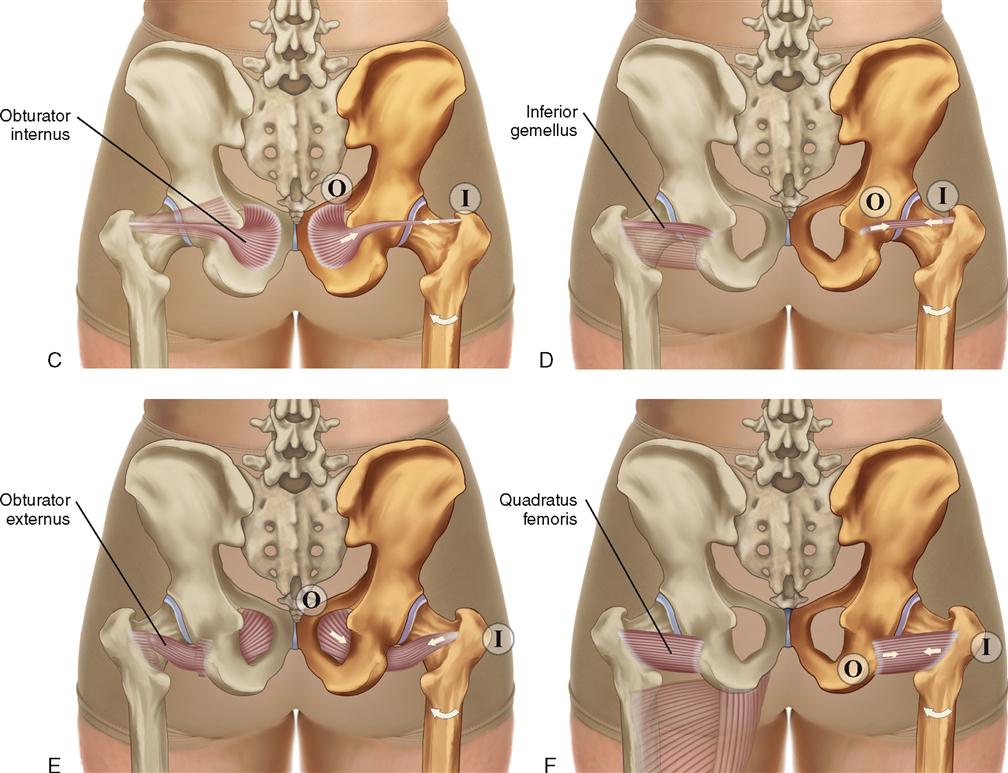

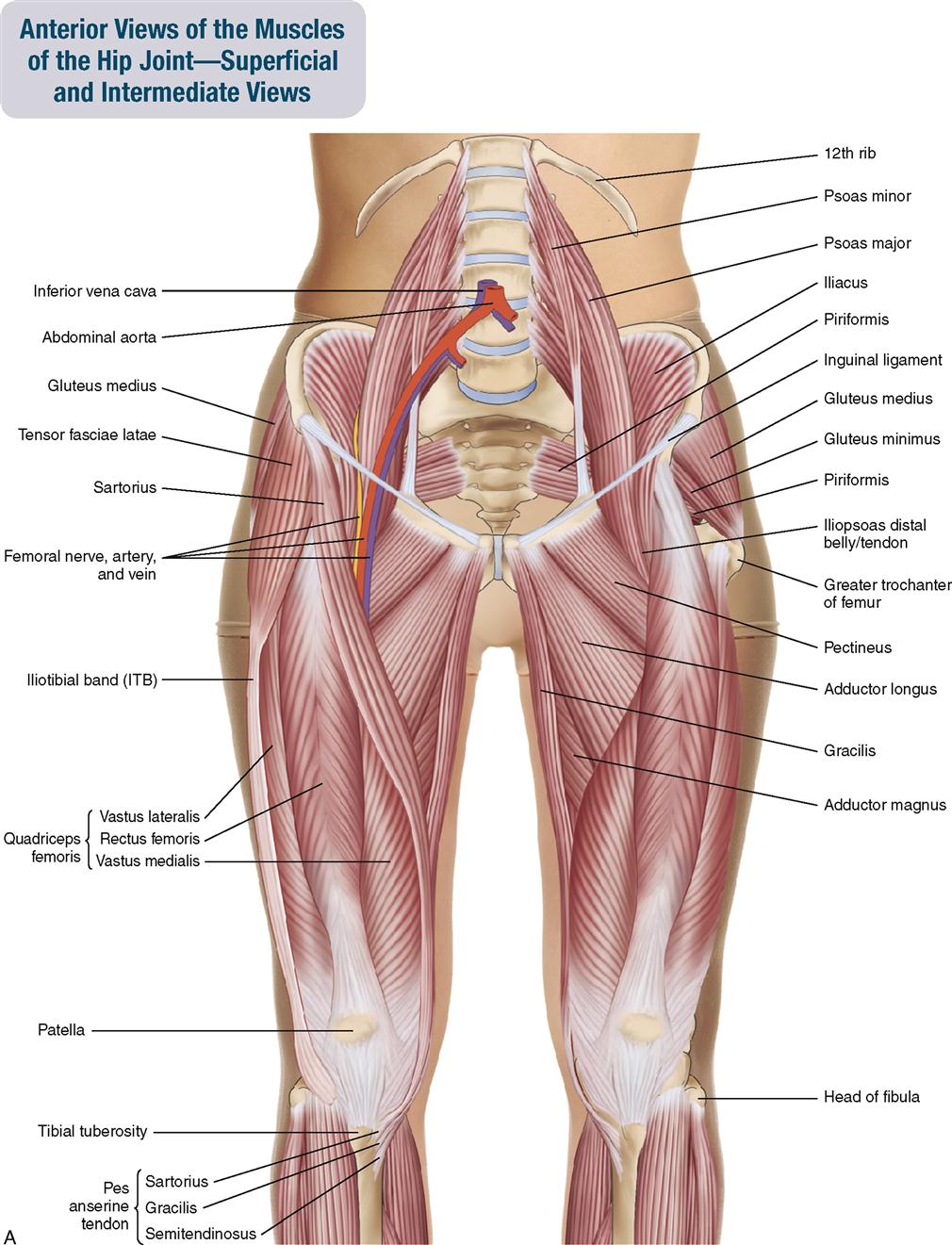

The muscles of this chapter are involved with motions of the thigh or pelvis at the hip joint and/or motions of the leg or thigh at the knee joint. The psoas major also crosses the lumbar vertebral joints and can therefore move the spine. The bellies of the gluteal and deep lateral rotator groups and the iliacus are located on the pelvis. The bellies of the psoas major and minor are located in the abdomen. The bellies of the adductor, quadriceps femoris, and hamstring groups, as well as the tensor fasciae latae and sartorius, are located in the thigh.

As a general rule, muscles that move the hip joint have their origin (proximal attachment) on the pelvis and their insertion (distal attachment) on the thigh (or leg). These muscles move the thigh relative to the pelvis or the pelvis relative to the thigh. Muscles that move the knee joint have their origin (proximal attachment) on the pelvis or thigh and their insertion (distal attachment) on the leg. These muscles move the leg relative to the thigh or the thigh relative to the leg.

The companion CD at the back of this book allows you to examine Chapter 10 muscles, layer by layer, and individual muscle palpation technique videos are available in the Chapter 10 folder on the Evolve website. Furthermore, if you want to read updated books and articles about muscles of the pelvis and thigh everyday, you should download Clinical Tree app on your phone. It is easy to save articles or books for offline access, which is ideal for preparing for exams, presentations, or patient consultations.

OVERVIEW OF FUNCTION: MUSCLES OF THE HIP JOINT

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for the functional groups of muscles of the hip joint:

If a muscle crosses the hip joint anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the anterior surface of the thigh toward the anterior surface of the pelvis; or it can anteriorly tilt the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the anterior surface of the pelvis toward the anterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the anterior surface of the thigh toward the anterior surface of the pelvis; or it can anteriorly tilt the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the anterior surface of the pelvis toward the anterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the posterior surface of the thigh toward the posterior surface of the pelvis; or it can posteriorly tilt the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the posterior surface of the pelvis toward the posterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the posterior surface of the thigh toward the posterior surface of the pelvis; or it can posteriorly tilt the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the posterior surface of the pelvis toward the posterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint laterally with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can abduct the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the lateral surface of the thigh toward the lateral surface of the pelvis; or it can depress (laterally tilt) the same-side pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the lateral surface of the pelvis toward the lateral surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint laterally with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can abduct the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) by moving the lateral surface of the thigh toward the lateral surface of the pelvis; or it can depress (laterally tilt) the same-side pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the lateral surface of the pelvis toward the lateral surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint medially, it can adduct the thigh at the hip joint by moving the medial surface of the thigh toward the medial surface of the pelvis (standard action); or it can elevate the same-side pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the medial surface of the pelvis toward the medial surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the hip joint medially, it can adduct the thigh at the hip joint by moving the medial surface of the thigh toward the medial surface of the pelvis (standard action); or it can elevate the same-side pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action) by moving the medial surface of the pelvis toward the medial surface of the thigh.

Medial rotators of the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) wrap around the femur from medial to lateral, anterior to the hip joint. They can also ipsilaterally rotate the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action).

Medial rotators of the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) wrap around the femur from medial to lateral, anterior to the hip joint. They can also ipsilaterally rotate the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action).

Lateral rotators of the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) wrap around the femur from medial to lateral, posterior to the hip joint. They can also contralaterally rotate the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action).

Lateral rotators of the thigh at the hip joint (standard action) wrap around the femur from medial to lateral, posterior to the hip joint. They can also contralaterally rotate the pelvis at the hip joint (reverse action).

Reverse actions are common at the hip joint and tend to occur when the foot is planted on the ground, which causes the distal attachment to be fixed and therefore the proximal attachment to be mobile and move toward the distal attachment. The reverse actions wherein the pelvis moves at the hip joint are often as important as, if not more important than, the typically thought of standard mover actions of the thigh at the hip joint.

Reverse actions are common at the hip joint and tend to occur when the foot is planted on the ground, which causes the distal attachment to be fixed and therefore the proximal attachment to be mobile and move toward the distal attachment. The reverse actions wherein the pelvis moves at the hip joint are often as important as, if not more important than, the typically thought of standard mover actions of the thigh at the hip joint.

OVERVIEW OF FUNCTION: MUSCLES OF THE SPINAL JOINTS

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for the functional groups of muscles of the spinal joints:

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment (insertion) down toward the inferior attachment (origin) in front.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment (insertion) down toward the inferior attachment (origin) in front.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment down toward the inferior attachment in back.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment down toward the inferior attachment in back.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints laterally, it can perform same-side lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment down toward the inferior attachment on that side of the body.

If a muscle crosses the spinal joints laterally, it can perform same-side lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and/or head at the spinal joints by moving the superior attachment down toward the inferior attachment on that side of the body.

Reverse actions occur by moving the pelvic or lower spine attachment (origin) toward the upper spine attachment (insertion). This movement usually occurs when a person is lying down.

Reverse actions occur by moving the pelvic or lower spine attachment (origin) toward the upper spine attachment (insertion). This movement usually occurs when a person is lying down.

OVERVIEW OF FUNCTION: MUSCLES OF THE KNEE JOINT

The following general rules regarding actions can be stated for the functional groups of muscles of the knee joint:

If a muscle crosses the knee joint anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the leg at the knee joint by moving the anterior surface of the leg toward the anterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the knee joint anteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can extend the leg at the knee joint by moving the anterior surface of the leg toward the anterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the knee joint posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the leg at the knee joint by moving the posterior surface of the leg toward the posterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle crosses the knee joint posteriorly with a vertical direction to its fibers, it can flex the leg at the knee joint by moving the posterior surface of the leg toward the posterior surface of the thigh.

If a muscle wraps around the knee joint, it can rotate the knee joint (the knee joint can only rotate if it is first flexed). Medial rotators attach to the medial side of the leg. The biceps femoris is the only lateral rotator and attaches to the lateral side of the leg.

If a muscle wraps around the knee joint, it can rotate the knee joint (the knee joint can only rotate if it is first flexed). Medial rotators attach to the medial side of the leg. The biceps femoris is the only lateral rotator and attaches to the lateral side of the leg.

Reverse actions are common at the knee joint and tend to occur when the foot is planted on the ground, causing the distal attachment to be fixed and therefore the proximal attachment (the thigh) to be mobile and move toward the distal attachment (the leg).

Reverse actions are common at the knee joint and tend to occur when the foot is planted on the ground, causing the distal attachment to be fixed and therefore the proximal attachment (the thigh) to be mobile and move toward the distal attachment (the leg).

The reverse action of extension of the leg at the knee joint is extension of the thigh at the knee joint in which the anterior surface of the thigh moves toward the anterior surface of the leg.

The reverse action of extension of the leg at the knee joint is extension of the thigh at the knee joint in which the anterior surface of the thigh moves toward the anterior surface of the leg.

The reverse action of flexion of the leg at the knee joint is flexion of the thigh at the knee joint in which the posterior surface of the thigh moves toward the posterior surface of the leg.

The reverse action of flexion of the leg at the knee joint is flexion of the thigh at the knee joint in which the posterior surface of the thigh moves toward the posterior surface of the leg.

The reverse action of medial rotation of the leg at the knee joint is lateral rotation of the thigh at the knee joint; the reverse action of lateral rotation of the leg at the knee joint is medial rotation of the thigh at the knee joint.

The reverse action of medial rotation of the leg at the knee joint is lateral rotation of the thigh at the knee joint; the reverse action of lateral rotation of the leg at the knee joint is medial rotation of the thigh at the knee joint.

ATTACHMENTS

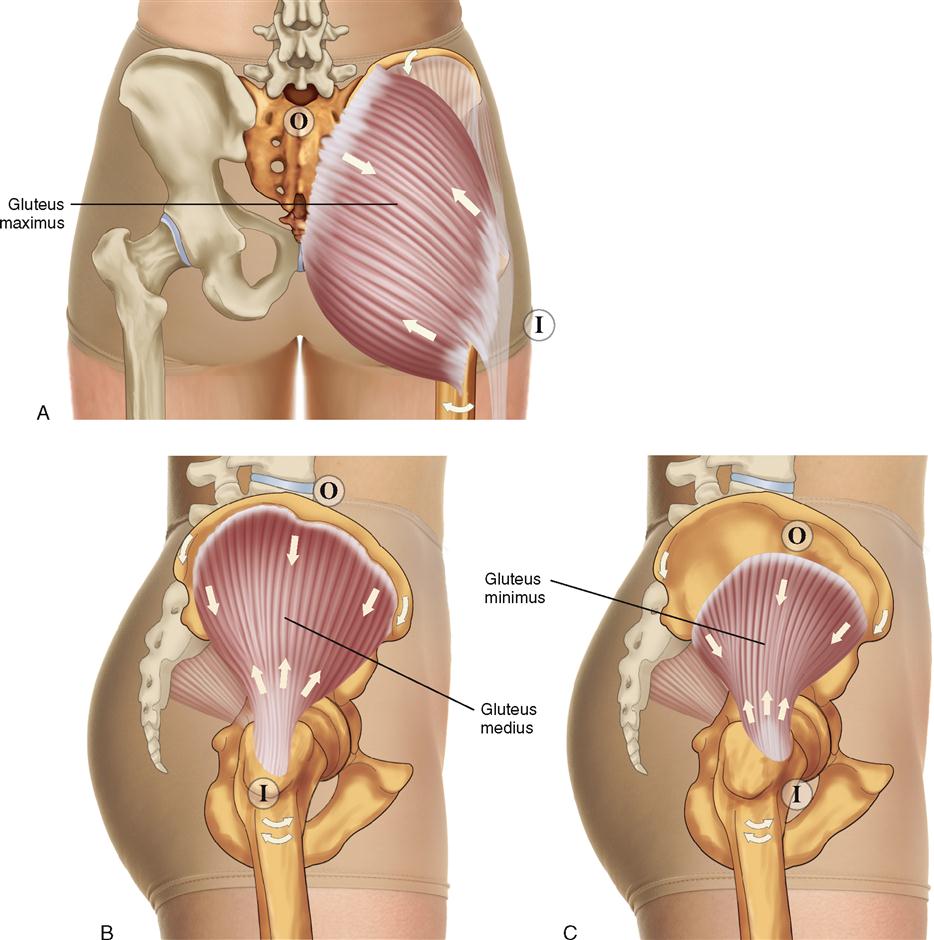

Gluteus Maximus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Gluteus Medius and Minimus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

ACTIONS

All of the actions listed for the gluteal muscles occur at the hip joint. The standard actions (insertion/distal attachment moving toward origin/proximal attachment) move the thigh at the hip joint; the reverse actions (origin/proximal attachment moving toward insertion/distal attachment) move the pelvis at the hip joint.

Gluteus Maximus

Gluteus Medius and Minimus

Extend the thigh (posterior fibers only).

Extend the thigh (posterior fibers only).

Flex the thigh (anterior fibers only).

Flex the thigh (anterior fibers only).

Laterally rotate the thigh (posterior fibers only).

Laterally rotate the thigh (posterior fibers only).

STABILIZATION

Stabilizes the thigh and pelvis at the hip joint.

INNERVATION

PALPATION

Gluteus Maximus

1. The client is prone. Place your palpating finger pads lateral to the sacrum. Place your resistance hand on the distal posterior thigh (if resistance is needed).

2. Ask the client to laterally rotate the thigh at the hip joint and then extend the laterally rotated thigh. Feel for the contraction of the gluteus maximus (Figure 10-5). Resistance can be added, if necessary.

3. With the muscle contracted, strum perpendicular to the fibers to discern the borders of the muscle.

4. Continue palpating the gluteus maximus laterally and inferiorly (distally) to its insertion (distal attachments) by strumming perpendicular to its fibers.

Gluteus Medius and Minimus

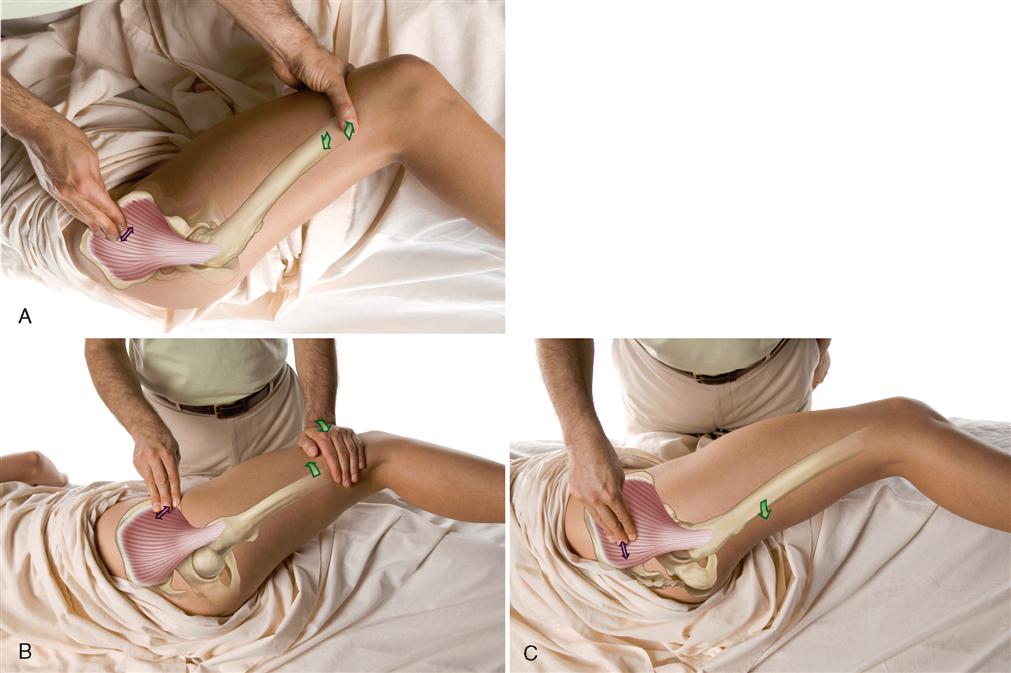

1. The client is side lying. Place your palpating finger pads just distal to the middle of the iliac crest, between the iliac crest and the greater trochanter of the femur. Place your resistance hand on the lateral surface of the distal thigh (if resistance is needed).

2. Palpating just distal to the middle of the iliac crest, ask the client to abduct the thigh at the hip joint. Feel for the contraction of the middle fibers of the gluteus medius (Figure 10-6, A). If desired, resistance can be added to the client’s thigh abduction with the resistance hand.

3. Strum perpendicular to the fibers, palpating the middle fibers of the gluteus medius distally toward the greater trochanter.

4. To palpate the anterior fibers, place your palpating hand immediately distal and posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and ask the client to gently flex and medially rotate the thigh at the hip joint. Feel for the contraction of the anterior fibers of the gluteus medius (Figure 10-6, B). Discerning the anterior fibers from the more superficial tensor fasciae latae is difficult.

5. To palpate the posterior fibers, place your palpating hand over the posterior portion of the gluteus medius, and ask the client to gently extend and laterally rotate the thigh at the hip joint. Feel for the contraction of the posterior fibers of the gluteus medius (Figure 10-6, C). Discerning the posterior fibers from the more superficial gluteus maximus is difficult.

6. Palpating and discerning the gluteus minimus deep to the gluteus medius is difficult. The gluteus minimus is thickest anteriorly. To palpate the gluteus minimus, follow the same procedure as for the gluteus medius, and try to palpate deeper for the gluteus minimus.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Thinking of the gluteus maximus as the speed skater’s muscle can be helpful. The gluteus maximus is powerful in extending, abducting, and laterally rotating the thigh at the hip joint, which are all actions that are necessary when speed skating.

Thinking of the gluteus maximus as the speed skater’s muscle can be helpful. The gluteus maximus is powerful in extending, abducting, and laterally rotating the thigh at the hip joint, which are all actions that are necessary when speed skating.

Usually a thick layer of fascia, called the gluteal fascia or the gluteal aponeurosis, overlies the gluteus medius muscle.

Usually a thick layer of fascia, called the gluteal fascia or the gluteal aponeurosis, overlies the gluteus medius muscle.

Lateral rotation of the thigh at the hip joint by the gluteal muscles acts to prevent medial rotation of the thigh and entire lower extremity, including the talus at the subtalar joint. This lateral rotation can stabilize the subtalar joint and prevent excessive pronation (dropping of the arch) of the foot.

Lateral rotation of the thigh at the hip joint by the gluteal muscles acts to prevent medial rotation of the thigh and entire lower extremity, including the talus at the subtalar joint. This lateral rotation can stabilize the subtalar joint and prevent excessive pronation (dropping of the arch) of the foot.

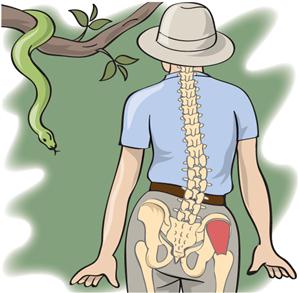

When the gluteus medius is tight, it pulls on and depresses the pelvis to- ward the thigh on that side. This results in a functional short leg (as opposed to a structural short leg wherein the femur and/or the tibia on one side is actually shorter than on the other side). Further, depressing the pelvis on one side creates an unlevel sacrum for the spine to sit on, and a compensatory scoliosis must occur to return the head to a level position.

When the gluteus medius is tight, it pulls on and depresses the pelvis to- ward the thigh on that side. This results in a functional short leg (as opposed to a structural short leg wherein the femur and/or the tibia on one side is actually shorter than on the other side). Further, depressing the pelvis on one side creates an unlevel sacrum for the spine to sit on, and a compensatory scoliosis must occur to return the head to a level position.

When one foot is lifted off the floor, the pelvis should fall to that side because it is now unsupported. However, the gluteus medius and minimus on the support-limb (opposite) side, which contract and create a force of same-side depression of the pelvis, prevent the pelvis from falling to that side. Therefore the pelvis remains level. With every step a person takes, contraction of the gluteus medius on the support side occurs. You can easily feel this when walking or even walking in place.

When one foot is lifted off the floor, the pelvis should fall to that side because it is now unsupported. However, the gluteus medius and minimus on the support-limb (opposite) side, which contract and create a force of same-side depression of the pelvis, prevent the pelvis from falling to that side. Therefore the pelvis remains level. With every step a person takes, contraction of the gluteus medius on the support side occurs. You can easily feel this when walking or even walking in place.

The gluteus medius and minimus contract to create a force of same-side pelvic depression when weight is simply shifted to one foot. Therefore the habitual practice of standing with all or most of the body weight on one side tends to cause the gluteus medius and minimus on that side to become overused and tight.

The gluteus medius and minimus contract to create a force of same-side pelvic depression when weight is simply shifted to one foot. Therefore the habitual practice of standing with all or most of the body weight on one side tends to cause the gluteus medius and minimus on that side to become overused and tight.

The gluteus medius can be thought of as the “deltoid of the hip joint” because it performs all the same actions to the thigh at the hip joint as the deltoid does to the arm at the glenohumeral joint.

The gluteus medius can be thought of as the “deltoid of the hip joint” because it performs all the same actions to the thigh at the hip joint as the deltoid does to the arm at the glenohumeral joint.

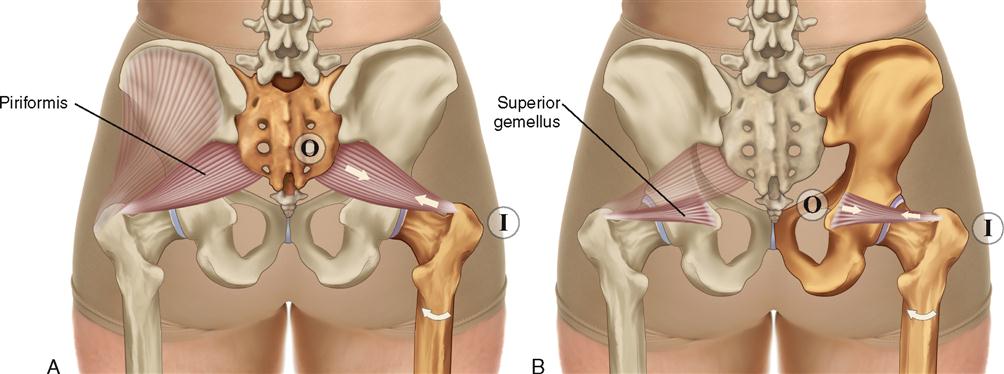

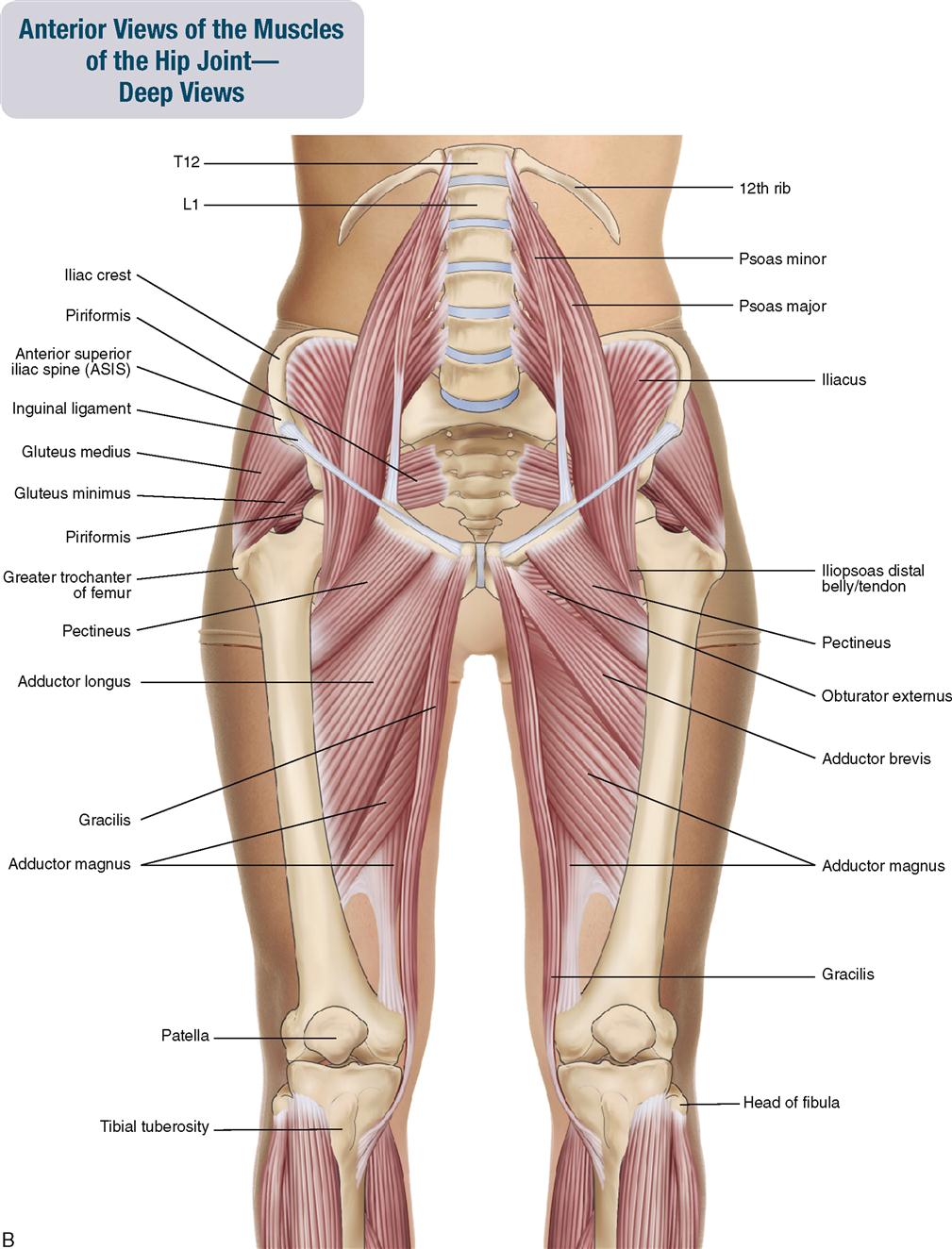

MUSCLES OF THE PELVIS AND THIGH: Deep Lateral Rotator Group

Piriformis; Superior Gemellus; Obturator Internus; Inferior Gemellus; Obturator Externus; Quadratus Femoris

Pronunciation pi-ri-FOR-mis • su-PEE-ree-or jee-MEL-us • ob-too-RAY-tor in-TER-nus • in-FEE-ree-or jee-MEL-us • ob-too-RAY-tor ex-TER-nus • kwod-RATE-us FEM-o-ris

ATTACHMENTS

Piriformis

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Superior Gemellus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Obturator Internus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Inferior Gemellus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Obturator Externus

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

Quadratus Femoris

Origin (Proximal Attachment)

Insertion (Distal Attachment)

ACTIONS

The standard actions (insertion/distal attachment moving toward origin/proximal attachment) move the thigh at the hip joint.

The reverse actions (origin/proximal attachment moving toward insertion/distal attachment) move the pelvis at the hip joint.

Piriformis

Superior Gemellus, Obturator Internus, Inferior Gemellus, Obturator Externus, Quadratus Femoris

STABILIZATION

INNERVATION

Piriformis

Superior Gemellus, Obturator Internus

Inferior Gemellus, Quadratus Femoris

Obturator Externus

PALPATION

1. The client is prone with the leg flexed to 90 degrees at the knee joint. Place your palpating finger pads just lateral to the sacrum, halfway between the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the apex of the sacrum. Place the support/resistance hand on the medial surface of the distal leg, just proximal to the ankle joint.

2. Gently resist the client from laterally rotating the thigh at the hip joint, and feel for the contraction of the piriformis (Figure 10-8).

3. Continue palpating the piriformis laterally toward the superior border of the greater trochanter of the femur by strumming perpendicular to the fibers as the client alternately contracts (against resistance) and relaxes the piriformis.

4. To palpate the quadratus femoris, place your palpating finger pads just lateral to the lateral border of the ischial tuberosity, and place your support/resistance hand on the medial surface of the distal leg, just proximal to the ankle joint. Follow the same procedure as for the piriformis, and feel for the contraction of the quadratus femoris (Figure 10-9).

5. Continue palpating the quadratus femoris laterally toward the intertrochanteric crest by strumming perpendicular to the fibers as the client alternately contracts (against resistance) and relaxes the quadratus femoris.

6. To palpate the other deep lateral rotators, either find the piriformis and palpate inferior to it, or find the quadratus femoris and palpate superior to it. Follow the same procedure used to palpate the piriformis and quadratus femoris by giving gentle resistance to the client’s lateral rotation of the thigh at the hip joint (Figure 10-10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree