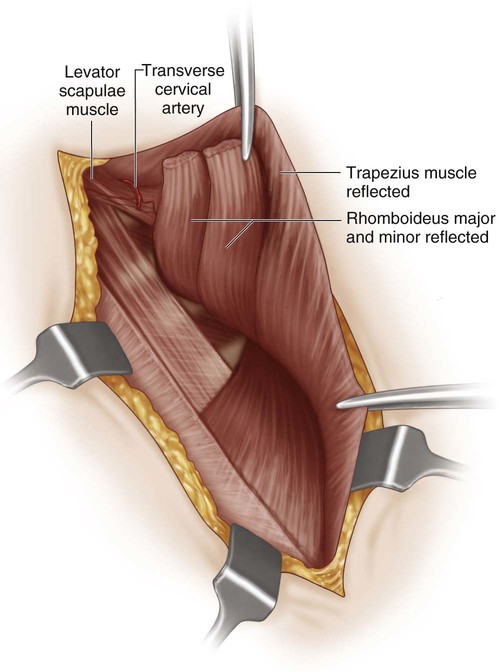

• Grade 1 (very mild): shoulder joints level and deformity invisible when the patient is dressed • Grade 2 (mild): shoulder joints level but deformity visible even when patient is dressed (as a prominence in the neck web) • Grade 3 (moderate): shoulder joint elevated 2–5 cm with deformity easily visible • Grade 4 (severe): shoulder greater than 5 cm elevated with scapula near occiput • The spinal accessory nerve provides innervation to the trapezius muscle and courses longitudinally along its anterior surface with the descending branch of the superficial cervical artery (deep surface when approached from posterior). • Branches of the dorsal scapular nerve innervate the rhomboid muscles. • The transverse cervical artery lies just anterior to the insertion of the levator scapulae and is at risk while releasing this muscle from the superomedial aspect of the scapula (Fig. 6). • Lateral dissection at the proximal scapula should be limited to avoid injury to the suprascapular neurovascular structures, located at the suprascapular notch. • The subclavian vessels are at risk during the clavicular osteotomy; curved Hohmann retractors placed subperiosteally will provide protection.

Modified Woodward Procedure for Sprengel’s Deformity

Indications

Operative intervention is considered in children with functional limitations, including those with decreased shoulder forward flexion and/or abduction. Children with a range of motion of less than 120° in either plane have the greatest potential for improvement after surgery.

Operative intervention is considered in children with functional limitations, including those with decreased shoulder forward flexion and/or abduction. Children with a range of motion of less than 120° in either plane have the greatest potential for improvement after surgery.

Operative intervention is also considered for aesthetic reasons due to the fact that the undescended scapula is quite noticeable.

Operative intervention is also considered for aesthetic reasons due to the fact that the undescended scapula is quite noticeable.

The Cavendish classification of Sprengel’s deformity (Cavendish, 1972) may be helpful in assessing the need for operative intervention based on appearance. A limited intervention such as excision of superomedial scapular prominence may be utilized for grades 1 and 2 whereas a more significant procedure to relocate the scapula, such as the Woodward procedure, may be more appropriate for grades 3 and 4.

The Cavendish classification of Sprengel’s deformity (Cavendish, 1972) may be helpful in assessing the need for operative intervention based on appearance. A limited intervention such as excision of superomedial scapular prominence may be utilized for grades 1 and 2 whereas a more significant procedure to relocate the scapula, such as the Woodward procedure, may be more appropriate for grades 3 and 4.

Age of intervention: The trend in treatment is for earlier intervention as it offers a better chance at functional improvement. Intervention between 3 and 6 years of age is favored, while others advocate intervention as early as 6–9 months. Nonetheless, some surgeons still offer the procedure in later childhood (5–9 years) or adolescence.

Age of intervention: The trend in treatment is for earlier intervention as it offers a better chance at functional improvement. Intervention between 3 and 6 years of age is favored, while others advocate intervention as early as 6–9 months. Nonetheless, some surgeons still offer the procedure in later childhood (5–9 years) or adolescence.

Examination/Imaging

The general appearance of the patient is assessed, with specific attention to the symmetry of the shoulders. The patient is evaluated with the arms at the sides and in various positions of function. When both scapulae are undescended, there is less asymmetry but still a noticeable abnormality. Figure 1 demonstrates the typical appearance of a right-sided unilateral deformity as seen in the anterior clinical view of a 3-year-old patient.

The general appearance of the patient is assessed, with specific attention to the symmetry of the shoulders. The patient is evaluated with the arms at the sides and in various positions of function. When both scapulae are undescended, there is less asymmetry but still a noticeable abnormality. Figure 1 demonstrates the typical appearance of a right-sided unilateral deformity as seen in the anterior clinical view of a 3-year-old patient.

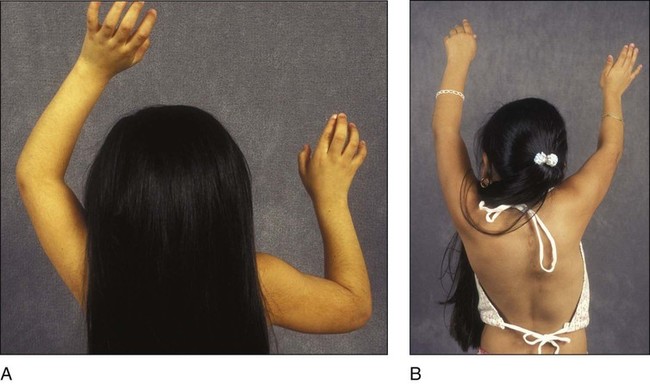

Shoulder range of motion is measured, with particular attention to active forward flexion and abduction. Figure 2 shows posterior clinical views of a 4-year-old patient with deficient right-sided abduction secondary to Sprengel’s deformity preoperatively (Fig. 2A) and postoperatively (Fig. 2B). Passive glenohumeral abduction and rotation are typically normal, whereas scapulothoracic motion is most severely affected. Additionally, upper extremity strength may be decreased.

Shoulder range of motion is measured, with particular attention to active forward flexion and abduction. Figure 2 shows posterior clinical views of a 4-year-old patient with deficient right-sided abduction secondary to Sprengel’s deformity preoperatively (Fig. 2A) and postoperatively (Fig. 2B). Passive glenohumeral abduction and rotation are typically normal, whereas scapulothoracic motion is most severely affected. Additionally, upper extremity strength may be decreased.

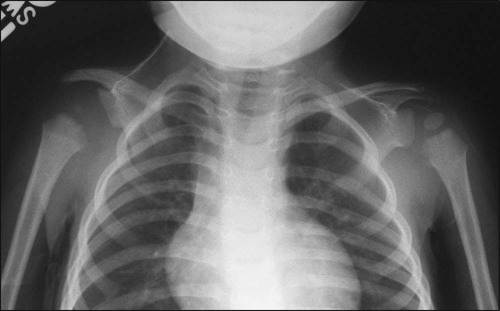

An anteroposterior radiograph to include both shoulders and centered on the clavicles is recommended to allow side-to-side comparison of the bony anatomy. The bilateral shoulder radiograph in Figure 3 demonstrates a typical hypoplastic, undescended, and rotated right scapula in the 3-year-old patient with right-sided deformity seen in Figure 1.

An anteroposterior radiograph to include both shoulders and centered on the clavicles is recommended to allow side-to-side comparison of the bony anatomy. The bilateral shoulder radiograph in Figure 3 demonstrates a typical hypoplastic, undescended, and rotated right scapula in the 3-year-old patient with right-sided deformity seen in Figure 1.

Computed tomography of both shoulders, including a three dimensional assessment, may be considered as it will provide a more detailed understanding of the anatomy.

Computed tomography of both shoulders, including a three dimensional assessment, may be considered as it will provide a more detailed understanding of the anatomy.

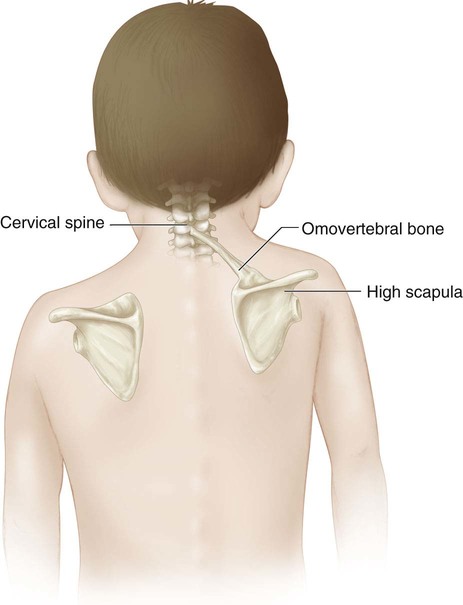

The physician should clinically evaluate for an accessory omovertebral bone connecting the superomedial aspect of the scapula to the mid- to lower cervical spinous process (Fig. 4); oblique shoulder radiographs and/or computed tomography scan may also be obtained.

The physician should clinically evaluate for an accessory omovertebral bone connecting the superomedial aspect of the scapula to the mid- to lower cervical spinous process (Fig. 4); oblique shoulder radiographs and/or computed tomography scan may also be obtained.

The patient is evaluated for the most common associated abnormalities, including cervical vertebral deformities, such as Klippel-Feil syndrome (30%), congenital scoliosis (25%), chest wall defects/hypoplasia (25%), and renal/genitourinary disorders (10%). Other associated anomalies include diastematomyelia, long bone deficits, and ray abnormalities of the hand or foot. Renal ultrasound and cervical spine computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be considered (Ross and Cruess, 1977).

The patient is evaluated for the most common associated abnormalities, including cervical vertebral deformities, such as Klippel-Feil syndrome (30%), congenital scoliosis (25%), chest wall defects/hypoplasia (25%), and renal/genitourinary disorders (10%). Other associated anomalies include diastematomyelia, long bone deficits, and ray abnormalities of the hand or foot. Renal ultrasound and cervical spine computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be considered (Ross and Cruess, 1977).

Consultations from spine and/or plastic surgeons are obtained prior to intervention to allow treatment of associated spine or chest wall deformities as needed.

Consultations from spine and/or plastic surgeons are obtained prior to intervention to allow treatment of associated spine or chest wall deformities as needed.

Surgical Anatomy

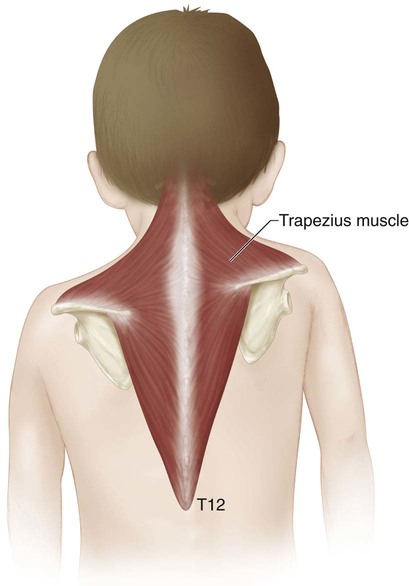

The trapezius, one of the primary muscles released during the Woodward procedure, has a very broad origin from the occiput to the T12 spinous processes (Fig. 5).

The trapezius, one of the primary muscles released during the Woodward procedure, has a very broad origin from the occiput to the T12 spinous processes (Fig. 5).

Thirty percent of patients will have an osseous or cartilaginous omovertebral bone linking the superior-medial angle of the scapula to the cervical spine (see Fig. 4). This is resected to allow for correction.

Thirty percent of patients will have an osseous or cartilaginous omovertebral bone linking the superior-medial angle of the scapula to the cervical spine (see Fig. 4). This is resected to allow for correction.

Neurovascular structures to be protected:

Neurovascular structures to be protected:

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine