Chapter 78 Hand Infections

General Approach to Hand Infections

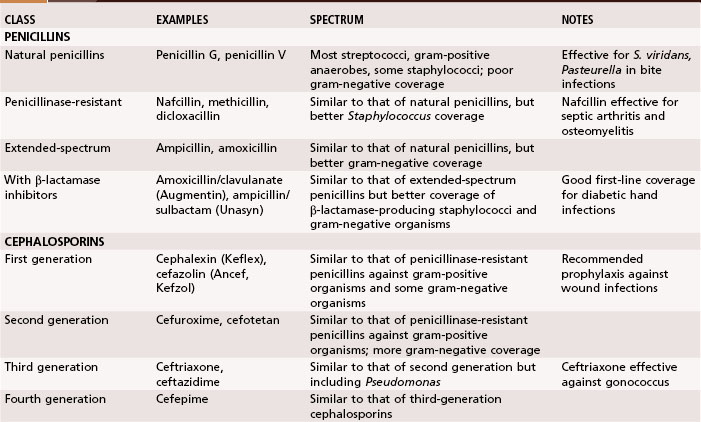

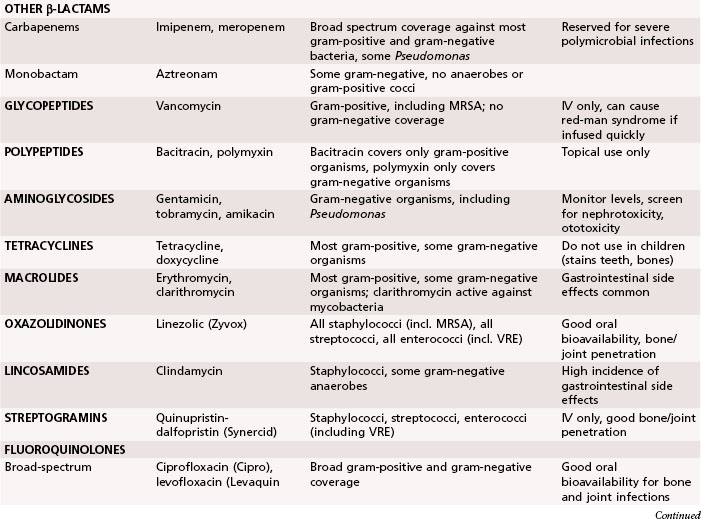

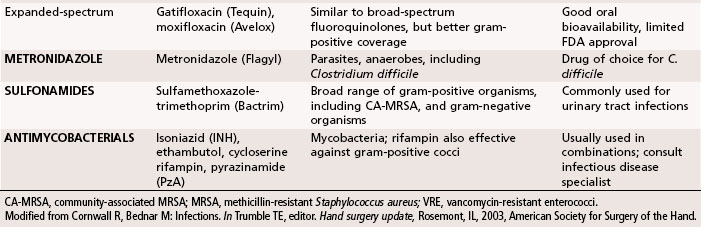

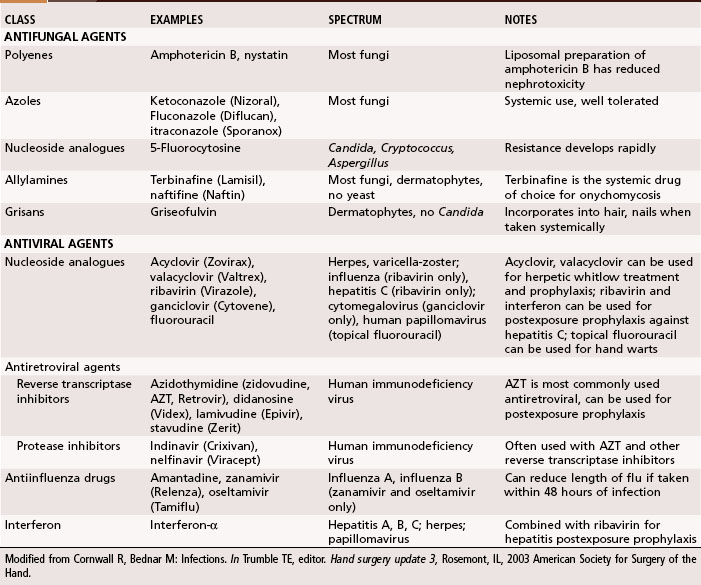

Antibiotics traditionally recommended for hand infections include a penicillinase-resistant penicillin or cephalosporin. When selecting antibiotics, it is important to be aware of the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which is growing in prevalence in hand infections. Antibiotic resistance is seen in up to 65% of Staphylococcus cultures. Vancomycin is effective against the gram-positive organisms, whereas ciprofloxacin is most effective against the gram-negative organisms. The addition of antibiotics effective against gram-negative organisms has been recommended for high-risk situations, such as infections in intravenous drug users and contaminated outdoor or farm injuries. In Tables 78-1 and 78-2 a summary is provided of the appropriate use of antibiotics, antifungal agents, and antiviral agents. Because of the constantly changing inventory of antibiotics and the variations in patient populations and wound flora, antibiotic selection should be based on a variety of considerations and include the assistance of an infectious disease specialist when needed.

Incision and Drainage of Hand Infection

Use a general anesthetic or distant regional block because a local anesthetic may not function in the septic environment, may spread the infection, and adds to an already swollen part.

Use a general anesthetic or distant regional block because a local anesthetic may not function in the septic environment, may spread the infection, and adds to an already swollen part.

Use a tourniquet, but before inflating it elevate the hand for 3 to 6 minutes to avoid limb exsanguination with an elastic wrap and the potential for proximal spread of the infection.

Use a tourniquet, but before inflating it elevate the hand for 3 to 6 minutes to avoid limb exsanguination with an elastic wrap and the potential for proximal spread of the infection.

After properly preparing and draping the area, make the incision for drainage as described for specific infections.

After properly preparing and draping the area, make the incision for drainage as described for specific infections.

After making the skin incision, always spread the deeper structures with blunt dissection to avoid injury to important nerves, vessels, and tendons.

After making the skin incision, always spread the deeper structures with blunt dissection to avoid injury to important nerves, vessels, and tendons.

Although an incision for drainage relieves pain and reduces the spread of infection, it also creates an open infected wound subject to further contamination. Copious irrigation with a pulsatile irrigator is an effective way to decrease contamination. Although wound closure after abscess drainage has been advocated, it probably is safer to return to the operating room in 3 to 5 days and close the wound secondarily, if the condition of the wound permits. If joints or flexor tendons have been exposed by skin necrosis, however, cover them at once to preserve their vital functions. In most instances, leave the wound open. Infections involving the tendon sheaths and joints usually result in some loss of function. Such loss of function is seen less often in superficial infections, unless surgical scars have adhered to adjacent structures, such as nerves or tendons.

Although an incision for drainage relieves pain and reduces the spread of infection, it also creates an open infected wound subject to further contamination. Copious irrigation with a pulsatile irrigator is an effective way to decrease contamination. Although wound closure after abscess drainage has been advocated, it probably is safer to return to the operating room in 3 to 5 days and close the wound secondarily, if the condition of the wound permits. If joints or flexor tendons have been exposed by skin necrosis, however, cover them at once to preserve their vital functions. In most instances, leave the wound open. Infections involving the tendon sheaths and joints usually result in some loss of function. Such loss of function is seen less often in superficial infections, unless surgical scars have adhered to adjacent structures, such as nerves or tendons.

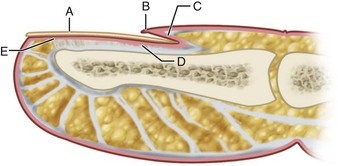

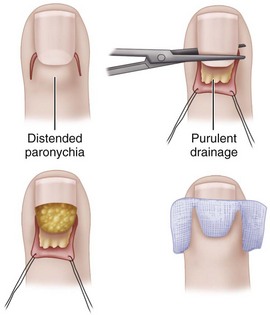

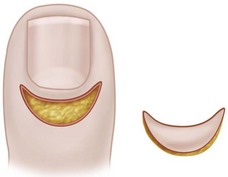

Paronychia

A paronychia (“runaround”) infection usually is caused by the introduction of S. aureus into the soft tissue fold around the fingernail (eponychium) associated with a hangnail or poor nail hygiene (Fig. 78-1). When an abscess forms in the eponychial or paronychial fold, it is known as a paronychia. It usually begins at one corner of the horny nail and travels under either the eponychium or the nail toward the opposite side. If an abscess is on one side only, it should be incised, angling the knife away from the nail to avoid cutting the nail bed, which would cause a ridge later. If the abscess is under one corner of the nail root, this corner should be removed. If it has already migrated to the opposite side and under the nail, a second incision should be made there, the skin folded back proximally, and the proximal one third of the nail excised. The wound is loosely packed with iodoform gauze for 48 hours for drainage (Fig. 78-2).

Chronic Paronychia

Eponychial Marsupialization

(BEDNAR AND LANE; KEYSER AND EATON)

After administering a digital block anesthetic, cleanse the finger with antiseptic and drape it appropriately.

After administering a digital block anesthetic, cleanse the finger with antiseptic and drape it appropriately.

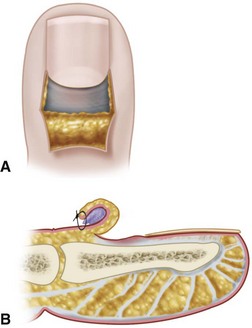

Excise a crescent of skin 3 mm wide parallel to the eponychium and extending from the radial to the ulnar borders (Fig. 78-3).

Excise a crescent of skin 3 mm wide parallel to the eponychium and extending from the radial to the ulnar borders (Fig. 78-3).

When using the Keyser and Eaton technique, remove all thickened tissue from the skin. Bednar and Lane leave the subcutaneous fat intact.

When using the Keyser and Eaton technique, remove all thickened tissue from the skin. Bednar and Lane leave the subcutaneous fat intact.

If nail irregularities are present, remove the nail.

If nail irregularities are present, remove the nail.

Cover the wound with petroleum/bismuth tribromophenate–impregnated gauze (Xeroform). If the nail is removed, place this gauze beneath the nail fold.

Cover the wound with petroleum/bismuth tribromophenate–impregnated gauze (Xeroform). If the nail is removed, place this gauze beneath the nail fold.

FIGURE 78-3 Eponychial marsupialization for treatment of paronychia. Symmetrical, crescent-shaped segment of skin is excised from dorsum of distal phalanx, leaving adequate bridge of skin and cuticle. SEE TECHNIQUE 78-2.

Pabari et al. described a “Swiss roll” technique for treatment of both acute and chronic paronychia in which the nail fold is elevated and reflected proximally over a nonadherent dressing and secured to the skin with a nonabsorbable suture (Fig. 78-4). Cited advantages of this technique are retention of the nail plate, rapid healing, and avoidance of a skin defect in the finger.

Felon

Incision and Drainage of Felons

When the abscess points volarward, causing necrosis of the overlying skin, drain it by excising the necrotic skin.

When the abscess points volarward, causing necrosis of the overlying skin, drain it by excising the necrotic skin.

When the abscess is in the distal pulp area pointing volarward toward the whorl of the fingerprint, it is best drained by a vertical incision begun distal to the skin crease and placed precisely in the midline to avoid the lateral branches of the digital nerve and to allow healing with minimal scar (Fig. 78-5).

When the abscess is in the distal pulp area pointing volarward toward the whorl of the fingerprint, it is best drained by a vertical incision begun distal to the skin crease and placed precisely in the midline to avoid the lateral branches of the digital nerve and to allow healing with minimal scar (Fig. 78-5).

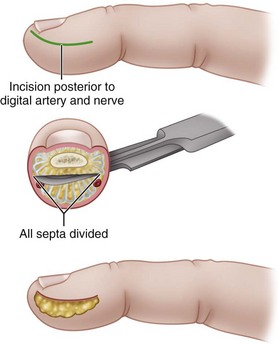

If the abscess is deep and is partitioned by the septa, make a longitudinal incision, usually away from the contact area of the finger, cutting through the partitions (Fig. 78-6).

If the abscess is deep and is partitioned by the septa, make a longitudinal incision, usually away from the contact area of the finger, cutting through the partitions (Fig. 78-6).

This incision must be accurate. Make the incision dorsal to the tactile surface of the finger and not more than 3 mm from the distal free edge of the nail; otherwise, the ends of the digital nerve would be painfully damaged. Blunt dissection with the tip of a small scissors or a mosquito hemostat avoids sharp injury to nerve endings, allowing disruption of the fibrous septa and adequate drainage. A J-shaped incision is sufficient; a fishmouth incision around the whole fingertip is slow to heal and can result in painful scarring, especially if it is placed too far palmar.

This incision must be accurate. Make the incision dorsal to the tactile surface of the finger and not more than 3 mm from the distal free edge of the nail; otherwise, the ends of the digital nerve would be painfully damaged. Blunt dissection with the tip of a small scissors or a mosquito hemostat avoids sharp injury to nerve endings, allowing disruption of the fibrous septa and adequate drainage. A J-shaped incision is sufficient; a fishmouth incision around the whole fingertip is slow to heal and can result in painful scarring, especially if it is placed too far palmar.

Irrigate the wound copiously, and pack it with iodoform gauze or sterile gauze bandage.

Irrigate the wound copiously, and pack it with iodoform gauze or sterile gauze bandage.

FIGURE 78-5 Midline vertical incision for drainage of abscess pointing volarward in distal pulp of finger. SEE TECHNIQUE 78-3.

Subfascial Space Infections

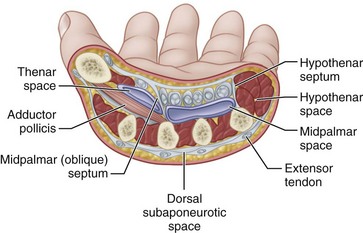

The potential spaces in the subfascial and deeper layers of the hand are infrequently infected. A high level of suspicion should lead to their detection and treatment. The recognized deep spaces of the hand include the interdigital web spaces, the midpalmar space, the thenar space, a less well-defined hypothenar space, the Parona space, and the dorsal subaponeurotic space (Fig. 78-7).

Web Space Infection (Collar Button Abscess)

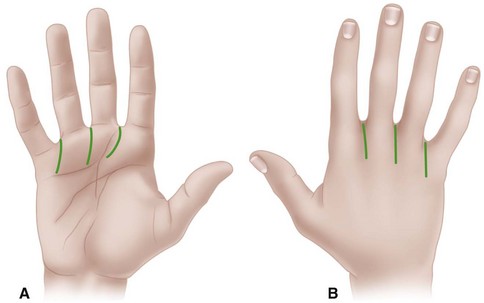

Web space infection usually localizes in one of the three fat-filled interdigital spaces just proximal to the superficial transverse ligament at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joints. Typically, the infection begins beneath palmar calluses in laborers. It may begin near the palmar surface, but because the skin and fascia here are less yielding, it may localize to drain dorsally. Here the tissue becomes obviously swollen, but the significant amount of the abscess remains nearer the palm. This may be the more dangerous part because, unless drained, it may spread through the lumbrical canal into the middle palmar space. Two longitudinal incisions usually are necessary for drainage: one on the dorsal surface between the metacarpal heads and the other on the palm, beginning distal to the distal palmar crease and curving proximally. Crossing the palmar creases at right angles to the crease should be avoided (Fig. 78-8). The web should not be incised.

Deep Fascial Space Infections

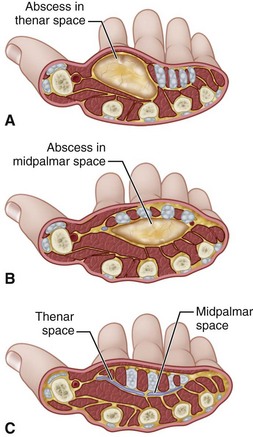

The palmar fascial space lies between the fascia covering the metacarpals and their contiguous muscles and the fascia dorsal to the flexor tendons. Its ulnar border is the fascia of the hypothenar muscles, and its radial border is the fascia of the adductor and other thenar muscles. This space is divided into a middle palmar space and a thenar space by a fascial membrane that passes obliquely from the third metacarpal shaft to the fascia dorsal to the flexor tendons of the index finger (Fig. 78-9). The hypothenar space has as its boundaries: the hypothenar septum laterally, the fifth metacarpal dorsally, and the hypothenar muscle fascia medially and palmar. The space of Parona is bordered by the pronator quadratus dorsally, the flexor pollicis longus laterally, the flexor carpi ulnaris medially, and the flexor tendons on the palmar aspect; it rarely is the site of abscess formation. Infections in these spaces are now rare because less extensive infections nearby usually are controlled by antibiotics before they spread. Abscesses in these spaces usually result from the spread of infection from other parts of the hand, typically from purulent flexor tenosynovial infections.

Incision and Drainage of Deep Fascial Space Infection

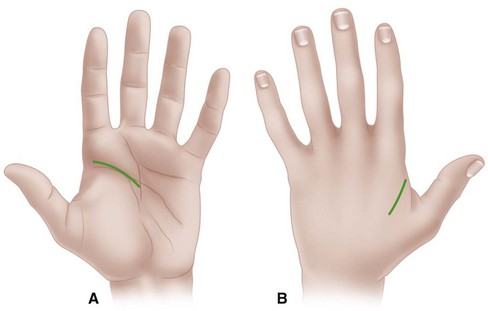

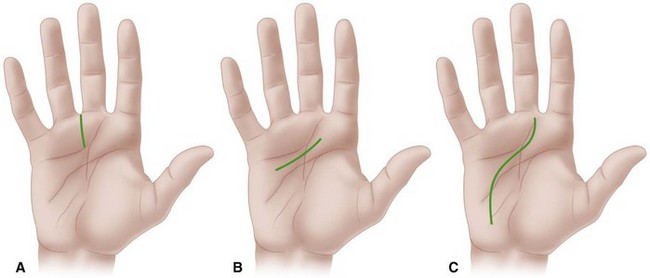

Drain the middle palmar space through a curved incision beginning at the level of the distal palmar crease, in line with the long finger and extending ulnarward to just inside the hypothenar eminence (Fig. 78-10). Other options include the longitudinal distal palm incision and the transverse palm incision.

Drain the middle palmar space through a curved incision beginning at the level of the distal palmar crease, in line with the long finger and extending ulnarward to just inside the hypothenar eminence (Fig. 78-10). Other options include the longitudinal distal palm incision and the transverse palm incision.

Enter the space on either side of the long flexor tendon of the ring finger with a blunt instrument, such as a hemostat, to avoid injury to neurovascular structures. Leave a drain in place if needed.

Enter the space on either side of the long flexor tendon of the ring finger with a blunt instrument, such as a hemostat, to avoid injury to neurovascular structures. Leave a drain in place if needed.

Drain the thenar space through a curved incision in the thumb web parallel to the border of the first dorsal interosseous muscle or along the medial side of the thenar crease (Fig. 78-11). Avoid the recurrent branch of the median nerve at the proximal end of this crease. Avoid sharp, deep dissection, using blunt dissection to delineate the extent of the abscess.

Drain the thenar space through a curved incision in the thumb web parallel to the border of the first dorsal interosseous muscle or along the medial side of the thenar crease (Fig. 78-11). Avoid the recurrent branch of the median nerve at the proximal end of this crease. Avoid sharp, deep dissection, using blunt dissection to delineate the extent of the abscess.

Drain Parona space infections through a straight or curved incision on the palmar forearm. Begin the incision just proximal to the wrist flexion crease, slightly medial to the midaxial line. Extend the incision proximally sufficiently to allow exposure of the flexor tendons and median nerve that lie immediately beneath the fascia.

Drain Parona space infections through a straight or curved incision on the palmar forearm. Begin the incision just proximal to the wrist flexion crease, slightly medial to the midaxial line. Extend the incision proximally sufficiently to allow exposure of the flexor tendons and median nerve that lie immediately beneath the fascia.

Retract the flexor tendons and median nerve, protecting them.

Retract the flexor tendons and median nerve, protecting them.

Drain the abscess, and irrigate the wound. If needed, place a Penrose drain or tube for irrigation in the wound.

Drain the abscess, and irrigate the wound. If needed, place a Penrose drain or tube for irrigation in the wound.

Apply a nonadherent gauze and bulky absorbent dressing. Splint the wrist in a position to allow functional motion of the fingers.

Apply a nonadherent gauze and bulky absorbent dressing. Splint the wrist in a position to allow functional motion of the fingers.

Change the bandage frequently, irrigating as needed. Usually, healing by secondary intention is satisfactory. If the infection and drainage can be controlled rapidly, secondary closure or skin grafting may be appropriate.

Change the bandage frequently, irrigating as needed. Usually, healing by secondary intention is satisfactory. If the infection and drainage can be controlled rapidly, secondary closure or skin grafting may be appropriate.

If the infection and drainage cannot be controlled rapidly, healing by secondary intention is preferred.

If the infection and drainage cannot be controlled rapidly, healing by secondary intention is preferred.

FIGURE 78-10 A, Distal longitudinal palmar incision. B, Transverse palmar incision. C, Extended longitudinal palmar incision. SEE TECHNIQUE 78-4.

Tenosynovitis

Postoperative Closed Irrigation

With the patient under suitable anesthesia and after appropriately preparing and draping the hand and arm, inflate a pneumatic tourniquet; however, to reduce the risk of spreading the infection, do not wrap the limb.

With the patient under suitable anesthesia and after appropriately preparing and draping the hand and arm, inflate a pneumatic tourniquet; however, to reduce the risk of spreading the infection, do not wrap the limb.

Expose the proximal end of the flexor sheath in the region of the A1 pulley by a straight transverse incision parallel to the distal palmar crease or by a zigzag incision in this area (Fig. 78-12). Expect to see serosanguineous or purulent fluid in the sheath.

Expose the proximal end of the flexor sheath in the region of the A1 pulley by a straight transverse incision parallel to the distal palmar crease or by a zigzag incision in this area (Fig. 78-12). Expect to see serosanguineous or purulent fluid in the sheath.

Open the sheath proximal to the A1 pulley, and swab the fluid to send for cultures.

Open the sheath proximal to the A1 pulley, and swab the fluid to send for cultures.

Make a second incision in the midaxial line on either side of the finger in the distal portion of the middle segment of the digit.

Make a second incision in the midaxial line on either side of the finger in the distal portion of the middle segment of the digit.

As an alternative, carefully make a transverse incision over the distal flexion crease.

As an alternative, carefully make a transverse incision over the distal flexion crease.

Open the flexor sheath distal to the A4 pulley.

Open the flexor sheath distal to the A4 pulley.

Using smooth forceps or hemostats, pass a 16-gauge or 18-gauge polyethylene catheter beneath the A1 pulley from proximal to distal in the flexor sheath for 1.5 to 2 cm. Distally place a small piece of rubber drain beneath the A4 pulley, and bring it out through the skin incision. Irrigate the sheath from proximal to distal with saline.

Using smooth forceps or hemostats, pass a 16-gauge or 18-gauge polyethylene catheter beneath the A1 pulley from proximal to distal in the flexor sheath for 1.5 to 2 cm. Distally place a small piece of rubber drain beneath the A4 pulley, and bring it out through the skin incision. Irrigate the sheath from proximal to distal with saline.

Close the wounds around the catheter and the rubber drain, leaving the distal wound sufficiently loose to allow fluid to drain. Suture the catheter to the palmar skin. Test the system for patency by irrigating freely with saline.

Close the wounds around the catheter and the rubber drain, leaving the distal wound sufficiently loose to allow fluid to drain. Suture the catheter to the palmar skin. Test the system for patency by irrigating freely with saline.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree