The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured bone of the carpals (Rizzo and Shin 2006), the mechanism of injury occurring from a compression of the wrist while in extension, as during a block or fall. Blood flow can also become disrupted, leading to complications in wound healing. Dislocations of the capitate with the lunate may also occur as a result of scaphoid fractures, termed a ‘perilunate dislocation’ (Bathala and Murray 2007). Here injury is as a result of forced extension, coupled with axial loading, and compression of the wrist.

Joints

The joints of the wrist and hand can be classified by their anatomical location and articulation with one another, to make up the radiocarpal joint (RC), midcarpal joint (MC), carpometacarpal joint (CMC), metacarpalphalangeal joint (MP), and interphalangeal joint (IP).

Radiocarpal joint

The radiocarpal joint of the wrist, which is formed by articulation of the radius with the scaphoid and lunate, and the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), with the lunate and triquetral, is often referred to as the common site for high intensive and chronic overuse injuries in sport (Bencardino and Rosenberg 2006; Tagliafico et al 2009). The triangular fibrocartilage is particularly susceptible to injury by way of forced extension and pronation, giving rise to issues of joint instability, disc degeneration and force distribution between the distal radial and ulnar joints (Melone and Nathan 1992). Several ligaments also aid in strengthening the radiocarpal joint (collateral, palmar and dorsal), allowing for movement in flexion, extension, abduction and adduction.

Midcarpal joint

The midcarpal joint is formed by two rows of carpals, the proximal row (scaphoid, lunate, triquetral and pisiform) and the distal row (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate and hamate). The carpal bones are closely packed together by intercarpal ligaments (dorsal, palmar and interosseous). As a result, flexion and abduction of the wrist occur more at the midcarpal joint, with extension and adduction greater at the radiocarpal joint.

Carpometacarpal joint

The carpometacarpal joints of the hand are formed by close articulation with the distal row of carpals and the five metacarpal bones, with the first carpometacarpal joint, being that of the thumb, classed as separate. The carpometacarpal joints are held together by dorsal and palmar ligaments, which allow for only a small degree of movement in joint glide. The thumb also has a lateral ligament, and due to its anatomical configuration, allows for a greater range of movement than the opposing fingers; allowing flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, opposition and reposition.

Metacarpalphalangeal joints

The metacarpalphalageal joints are where the fingers begin to become distinct from the hand. These are comprised of the five metacarpal bones articulating with the five proximal phalanges. The deep transverse metacarpal ligament holds all the MP joints together, allowing for flexion, extension, abduction and adduction. The second and third MP joints are quite rigid, making up the major stabiliser for the hand, whereas the fourth and fifth joints become increasingly mobile, in order to initiate the action that permits the closed grip of the hand.

The first metacarpalphalangeal joint of the thumb is separate from the other MP joints, to allow for greater abduction and adduction. In addition, the collateral ligament complex also provides stability, allowing for the thumb to adopt any position on the palmar aspect of the hand, and to provide a precision grip to the distal phalanges. An injury to the collateral ligament is particularly common in sports where the thumb is exposed, resulting in trauma from forced abduction and hyperextension, often from a direct contact with an opponent. In traumatic circumstances such as this, the stability of the joint can become compromised, leading to the need for medical intervention and wound repair.

Interphalangeal joints

The interphalangeal joints of the fingers are expressed as the proximal PIP and distal DIP interphalangeal joints, the DIP being furthest away from the hand. The interphalangeal joints are held closely together by collateral ligaments, which remain taught in both flexion and extension, unlike the collateral ligaments of the metacarpalphalageal joints, which are loose in extension. The collateral ligaments of the fingers are a common injury sustained in physical activity (Chomiak et al. 2000; Shewring and Matthewson 1993), occurring mainly in field and contact sports such as football and rugby.

Muscles

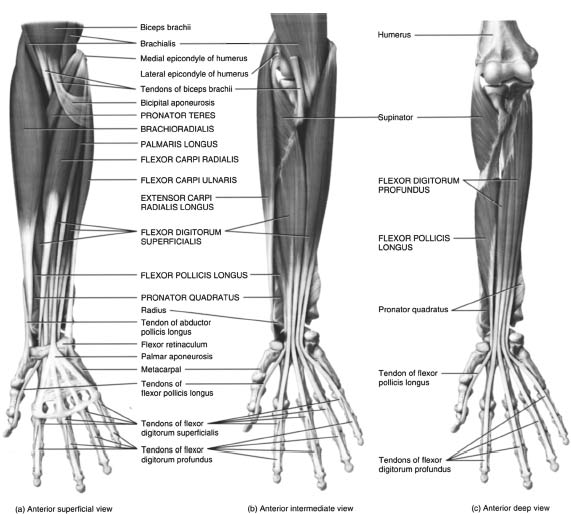

There are five muscles that act on the wrist joint. These are the flexor group; flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus and flexor carpi ulnaris, and the extensor group; extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi ulnaris (Figure 19.2). It is worth noting that a small percentage of individuals do not possess the palmaris longus, which aids to tighten the palmar fascia (Saied and Karamoozian 2009).

Figure 19.2 Extrinsic muscles of the wrist and hand (example). Reproduced, with permission, from Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, (11th ed). Tortora, G.J., & Derrickson, B., (2006).

There are several intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the hand, which co-exist to produce movement for the thumb and fingers. Three extrinsic muscles act on all four fingers. These include flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus and extensor digitorum. Two smaller muscles also help to assist with extension of the index finger and fifth finger, respectively. These are extensor indicis and extensor digiti minimi. Disruption of the finger flexor tendon pulley is one of the most frequently occurring injuries in rock climbing, due to bowstringing of the tendon during the closed ‘crimp-hand’ position (Schöffl and Schöffl 2006). Considerable friction has also been shown to be apparent in a study by Moora, Nagya, Snedekera and Schweizer (2009), reporting that the fingers, particularly at 90-degree flexion, stress the PIP joint.

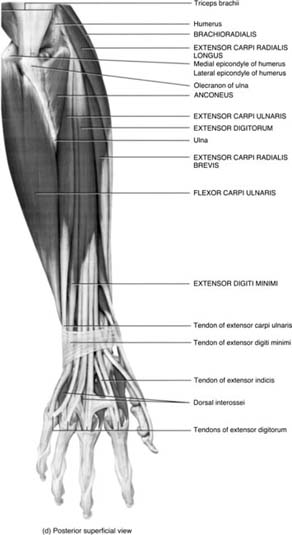

There are a total of 11 intrinsic muscles in the hand that act upon the proximal phalanges and middle and distal phalanges. These muscles include 4 lumbricales, 4 dorsal and 3 palmar interrossei muscles that lie between the metacarpal bones (Figure 19.3). The muscles most commonly injured within the hand are the interossei, usually by overstretching the fingers. Pain and swelling are often localised, and restriction in movement occurring in either abduction (dorsal interossei) or adduction (plantar interossei).

Figure 19.3 Intrinsic muscles of the hand (example). Reproduced, with permission, from Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, (11th ed). Tortora, G.J., & Derrickson, B., (2006).

Eight muscles co-exist to produce the movements of the thumb. These include the extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, abductor pollicis longus, and flexor pollicis longus, which are extrinsic in origin, and the flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, abductor pollicis brevis and the adductor pollicis, which converge to form the thenar eminence. Three more intrinsic muscles of the hand also act on the little finger, including the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis and opponens digiti minimi, which converge on the medial aspect of the hand to form the hypothenar eminence.

Assessment and management of wrist and hand injuries

Clinical examination of the wrist and hand is necessary in order to delineate injured structures and to assess the need for referral. The protocol of assessment most commonly recognised in the UK for sports rehabilitation is SOAP (Brown et al. 2007), the acronym for subjective, objective, assessment and prognosis. After completion of the subjective portion of the assessment, which includes detailing both personal details and medical history, the rehabilitator should now begin to conduct the objective portion, which involves the physical assessment.

Objective assessment

Palpation

Palpation should occur with the athlete seated, with the forearm, wrist and hand in a relaxed position. Because of the superficial nature and complexity of the wrist and hand, a thorough knowledge of structural and functional anatomy should be gained beforehand in order to understand the extent of any musculoskeletal injury

Range of motion

Wrist and hand motions occur in a variety of different planes, which can often be thought of as corresponding to the joint actions of the elbow and the shoulder. Testing includes active and passive movements for the wrist in flexion, extension, radial and ulnar deviation, MCP joints in flexion, extension, abduction and adduction, and interphalangeal joints in flexion and extension. The thumb is also included in flexion and extension, and also abduction, adduction and circumduction. The purpose of range of motion assessment is to assess physiological and accessory motion, to differentiate injury between anatomical structures, and to assess end feel for abnormal movement.

Special testing

Special tests of the wrist and hand extend to physiological, neurological and also vascular examinations, to conclude or exclude pathology. These tests include examinations to both soft tissue and bony articulations, for the presence of acute and chronic inflammation, stress fractures and underlying medical conditions.

Functional assessment

Functional assessment is a component that is often overlooked during injury assessment, as it is important to gauge the physical capabilities of the athlete. Several exercises can be used here to assess functional capacity of the wrist and hand, which include sports-specific activities already performed by the athlete. In turn this will help assess motion, stability, strength, balance and coordination.

The rehabilitator may also perform an individualised approach towards injury assessment, through the use of a differential diagnosis. Here the assessment of other closely affected structures of the wrist and hand, namely the head, neck, shoulder and elbow, are conducted to measure the extent of those injuries. In addition, testing should also always be conducted in comparison to the unaffected limb, to gain a comparable sign of what appears to be normal to the athlete.

Common UK sporting wrist and hand injuries

Research has shown that there are a number of common wrist and hand injuries that readily occur within UK sports (Rettig 2004). The bulk of these injuries sustained from the very nature of participating in these sports. For the purposes of review, the most common injuries will be discussed, together with assessment and conservative management, according to scope of practice for GRSs, who operate exclusively within the UK. The full list of injuries, however, can be seen illustrated as they are presented according to each sport (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1 UK sports and associated injuries (Rettig 2003, 2004)

| Sport | Associated injuries | Occurrence |

| Rugby Union and Rugby League | Mallet finger DeQuervain’s tenosynovitis Metacarpal fractures Scaphoid fractures Trigger finger/thumb Jersey finger | Direct trauma from player contact |

| American Football | Hyper extension wrist injury Flexor digitorum profundus ruptures Perilunate dislocation CMC and PIP joint injuries: collateral ligament tears, dislocations, fractures and volar plate injuries Intra-articular tears | Direct trauma and deviation forces |

| Boxing | Extensor tendon injury: Boxer’s knuckle | Repetitive trauma |

| Tennis (other racquet sports such as squash and badminton) | Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) dysfunction Carpal tunnel syndrome Ulnar wrist pain Hook of hamate fracture Kienbock’s disease | Repetitive and overuse injury |

| Golf | Wrist flexor tendonitis | Overuse injury |

| Basketball | Sprained wrist Boutonniere deformity Finger fractures Gamekeeper’s thumb | Direct trauma and falling |

| Gymnastics | Distal radius fractures Avascular necrosis of the capitate Ulnocarpal abutment syndrome Dorsal impingement | Repetitive loading and axial compression |

| Rock climbing | Pulley disruption | Falling |

| Hockey | Gamekeeper’s thumb Hand/finger fractures Finger tendon and ligament sprains | Direct trauma and player contact |

| Cricket | Bennett’s fracture Carpal tunnel Mallet finger Wrist arthritis | Repetitive trauma and overuse injury |

| Cycling | Guyon’s canal syndrome | Repetitive loading and compression |

| Weightlifting | Subluxation of the ECU Intersection syndrome | Overuse syndrome |

Acute soft tissue injuries

Athletes participating in high intensive and contact sports will no doubt be affected by acute soft tissue injuries. The role of the sports rehabilitator, therefore, is to work on minimising those risks, while focusing on rehabilitating those injuries. The classification of acute soft tissue injuries can be subdivided into sprains, strains and contusions.

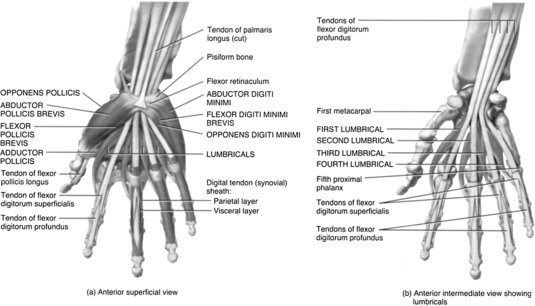

Gamekeeper’s thumb

A common injury sustained by players in football and hockey, the gamekeeper’s thumb is a sprain of the ulnar collateral ligament, also termed the ‘skier’s thumb’, for the mechanism in which the injury is sustained (Figure 19.4).

Figure 19.4 Skier’s thumb (example). Reproduced, with permission, from Clinical Practice of Sports Injury Prevention and Care: Olympic Encyclopaedia of Sports Medicine, Volume V. Renstrom, P.A., F., H., (1994).

Signs and symptoms

An athlete with gamekeeper’s thumb will present with pain and swelling on the palmar aspect of the thumb joint, between the web space of the thumb and the hand. Palpation will show a palpable defect in the instance of full rupture, with instability evident on bilateral comparison, with the thumb in abduction. Partial ruptures will elicit moderate joint laxity with a definite end feel. Further investigation by imaging can also confirm suspicion of tendon avulsions.

Management

In the immediate instance of injury to the ulnar collateral ligament, ice packs and compression are the best forms of treatment (Janoff 1999). Ultrasound can also be effective in the early stages to diagnose injury (Chuter et al. 2009; Malik et al. 2009), followed by massage and mobilisation, to aid in ligament repair and restore function (Alexy and De Carlo 1998). Thumb strength and dexterity can also be improved by using hand therapy balls and therapeutic putty (Alexy and De Carlo 1998; Shafer-Crane 2006; Wilson et al. 2008), whereas grip and thumb strengthening devices may be useful in restoring normal hand and thumb motion.

Complications in healing

Where there is a complete rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament, further medical intervention may be necessary. As in some cases the ruptured ligament may have become entangled in the soft tissue at the base of the thumb, known as a “Stener lesion”, which will further complicate the procedure for conservative management and present a delay in wound healing (Ebrahim et al. 2006). Although, ruptured ulnar collateral ligaments without Stener lesions, have a good capacity to heal without complication. Following successful rehabilitation, return to sporting activities is possible. Returning to full sport is considered once the athlete has regained full functional ROM, with 90% strength of the unaffected part, and pain and swelling are minimal (Stracciolini et al. 2007).

Injury prevention

For football (soccer) goalkeepers and rugby players, preventative taping can be effective in aiding thumb joint stability and preventing further injury, and in sports where no catching is required, a thumb brace can also provide an alternative means to a permanent wrist support (Alexy and De Carlo 1998)

Mallet finger

Another common injury sustained in field and contact sports is mallet finger. Mallet finger is sustained from forceful flexion of an extended distal DIP joint, such as when a player has mistimed a shot or catching the ball.

Signs and symptoms

An athlete with mallet finger will present with pain at the dorsal DIP joint, with an inability to actively extend the joint, demonstrating a characteristic flexion deformity. If the tendon is only partially stretched, then movement may be restricted by 15–20 degrees extension. However, if a full rupture is present, then movement will be limited by 30–40 degrees extension, although full passive motion is typically preserved (Micheo 2003).

Management

The majority of mallet finger injuries are treated conservatively with rehabilitation. Ice packs can be useful to relieve pain in the early stages. The terminal interphalangeal joint (the joint in the finger closest to its tip) should be splinted in slight hyperextension (an overly straightened position), without immobilising any of the other joints of the injured finger (Janoff 1999). This position can then be maintained to allow time for wound healing.

Treatment

Treatment includes active DIP flexion exercises (making a full fist) that act to regain strength and mobility of the injured finger. This should be practised without the splint for 10 minutes every hour for the first two weeks (Teoh and Lee 2007), followed by several weeks of DIP flexion exercises with an extended PIP joint (Walshaw 2004).

Complications in healing

It is important to isolate the DIP joint during evaluation to ensure extension is from the extensor tendon and not the central slip, the absence of full passive extension possibly indicating a bony or soft tissue entrapment (Bach 1999; Lee and Montgomery 2002). Furthermore, bony avulsion fractures are present in one-third of patients with mallet finger, (Lairmore and Engber 1998; Palmer 1998).

Injury prevention

In sports such as basketball, cricket, and rugby it may be sensible to tape the fingers to provide further support to the joints. In individuals with a previous history, it is wise to wear a finger splint as protection.

Jersey finger

A disruption of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon, also known as jersey finger, commonly occurs when an athlete’s finger catches on another player’s clothing, usually while playing a team sport such as football or rugby. As the athlete pulls away, the finger is forcibly straightened while the profundus flexor tendon continues to contract. The ring finger is the weakest digit of the four fingers, accounting for 75% of all reported cases (Hankins and Peel 1990).

Signs and symptoms

An athlete with jersey finger will present with pain and swelling at the volar aspect of the DIP joint, and will be unable to bend the tip of the affected finger. Tenderness may also felt elsewhere along the finger or hand, if the profundus tendon has become retracted. The digitorum profundus tendon can be evaluated by holding the affected finger’s MCP and PIP joints in extension while the rest remain in flexion, and performing a concentric contraction of the affected DIP joint (Hankins and Peel 1990). A positive sign for rupture to the digitorum profundus tendon is that the DIP joint should not move.

Management

Immediate management of jersey finger includes diagnostic imaging to confirm suspicion of an avulsion fracture, as complications can quickly arise in the case of tendon retractions (Mastey et al. 1997). Athletes with confirmed or suspected jersey finger should also be referred for medical consultation. Following medical intervention, rehabilitation should consist of passive range of motion exercises followed by a return to normal activity only after a period of several weeks, during which time movement is restricted in order to promote wound repair.

Boutonnière deformity

A common injury to the central slip extensor tendon (boutonnière deformity) occurs when the PIP joint is forcibly flexed while actively extended. It is a common injury among basketball players. Volar dislocation of the PIP joint can also cause central slip tendon ruptures (Perron et al. 2001).

Sign and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of boutonnière deformity include pain and localised swelling to the PIP joint. The PIP joint should be evaluated by holding the joint in a position of 15–30 degrees of flexion. If the PIP joint is injured, then the athlete will be unable to actively extend the joint, however, passive extension will be possible. Tenderness over the dorsal aspect of the middle phalanx will also be present.

Management

The PIP joint should be splinted in full extension for the first six weeks of healing, and in cases where no avulsion has taken place, or the avulsion involves less than one third of the joint. All available splints can be used to treat PIP injuries, except for the stack splint, which is used only for DIP injuries. As with mallet finger, extension of the PIP joint must be maintained continuously. If full passive extension is not possible, then the rehabilitator should refer the athlete.

Complications in healing

If an avulsion fracture is present on imaging then medical intervention may be necessary to prevent future complications, as a delay in the proper treatment may cause permanent deformity. A boutonnière deformity usually develops over a period of several weeks, as the intact lateral bands of the extensor tendon slip inferiorly. However, a boutonnière deformity will also occur more acutely.

Injury prevention

In sports such as basketball, cricket, and rugby it may be sensible to tape the fingers to provide further support to the joints. Athletes with PIP joint injuries may also continue to participate in athletic events during the splinting period, although some sports are difficult to play with a fully extended PIP joints.

Extensor pollicis longus rupture

A tendon rupture of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) is a recognised complication of distal radial fractures and their fixation with dorsal radial plates and pins. A number of other conditions including internal fixation of wrist fractures and inflammatory arthropathies have also been reported as aetiological factors of EPL tendon rupture (Ansede et al. 2009).

Management

The EPL tendon is complex and if a rupture occurs then medical intervention may be necessary. The standard procedure for this type of injury is to use the extensor indicis proprius (EIP) tendon. The tendon is then transferred from its normal location to replace the function of the EPL. There however some disadvantages to using the EIP, as Bullon (2007) states that the EPL may not have sufficient tendons, therefore using the accessory abductor pollicis longus (AAPL) is preferred, as transference can then be conducted without affecting the function of the APL.

Complications in healing

Not all people have this tendon, as it is present in approximately 85% of the general population. However, Bullon (2007) states that the AAPL could be used successfully in restoring function of the ruptured EPL, as everyday newer surgical procedures are being conducted, which have many advantages over other tendon transfers for this type of injury. Wimsey, Kurian and Jeffery (2006) also state that there is a conservative approach to this condition, which would be to immobilise the wrist joint in a mallet splint for 12 weeks. However, this approach would only be advocated to the younger population, as complications can occur from immobilisation of the joints, such as muscle atrophy and weakness, which will hinder effective management.

Other acute soft tissue injuries

Triangular fibrocartilage complex tears

The triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) sits between the distal end of the ulna and the triquetrum and part of the lunate. It consists of the triangular fibrocartilage, the ulnar meniscus homolog, the ulnar collateral ligament, carpal ligaments and the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon sheath. Testing for the TFCC is to place the wrist in extension and ulnar deviation and then rotate. This movement, as in the forehand volley, relates to overloading of the complex.

The integrity of the TFCC is closely bound up with the stability of the distal radio-ulnar joint (DRUJ). In a study by Adlercreutz, Aspenberg and Lindau (2000), it was shown that a complete tear of the TFCC is almost always associated with instability of the DRUJ. Instability of the DRUJ is also associated with generalised capsuloligamentous laxity. Often pain on the ulnar side of the wrist is multifactorial and stability-related. Another underlying cause of compression injuries to the TFCC is ulnar variance.

Collateral ligament sprains

Collateral ligament injuries of the MCP, PIP and IP joints can occur in many types of sport. Injuries of the collateral ligaments of the MCP joints are seldom but instability can present if the tear is complete. Injury to the PIP joint is quite common in athletes and team sports such as volleyball, basketball and rugby. The majority of collateral ligament injuries can be treated by splinting or taping the affected part to the adjacent fingers, known as ‘buddy taping’, in order to provide additional support (Sennet 2004). The IP joint of the thumb is similar to the PIP joint of the fingers, and as such, should be treated in much the same way.

Wrist sprains

Wrist sprains typically occur after a trip or fall, resulting in stretching or tearing of the ligaments of the wrist. Common causes of wrist sprain include falls during team sports, such as when a basketball player is tackled during a jump shot, or a rugby player barged from the side. Moreover, if the tissues are inflexible and weak, the risk of injury increases. However, the majority of these injuries can be treated conservatively, and seldom result in prolonged loss of sporting activity.

Contusions

Contusions of the wrist and hand are a common injury, because of the many superficial tendons and bony prominences that are exposed. Contusions are rarely serious, and can be treated conservatively over time. However, care must be taken not to rule out more serious injury, such as ligament sprains, tendon injuries and joint fractures.

Chronic and overuse injuries

Repetitive actions can take their toll in team and action sports, resulting in chronic inflammatory issues and degenerative pathologies. The repetitive cycle of injury that can occur from an acute injury that is poorly managed is also a source of chronic instability, resulting in faulty recruitment from scar tissue, chronic inflammation and irritation from repetitive forces. In sports such as tennis, gymnastics and rock climbing, the wrists are exposed to a greater frequency of joint irritation, from the dissipation of load through the upper extremity. Therefore, the role of the sports rehabilitator is to work on breaking the cycle of injury and promote effective wound healing, and in the instances where injuries are idiopathic in nature, to work on minimising those risks to aid in ensuring longevity for the athlete and their sport.

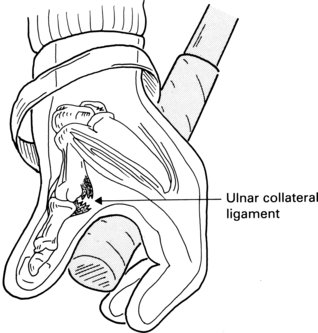

De Quervain’s disease

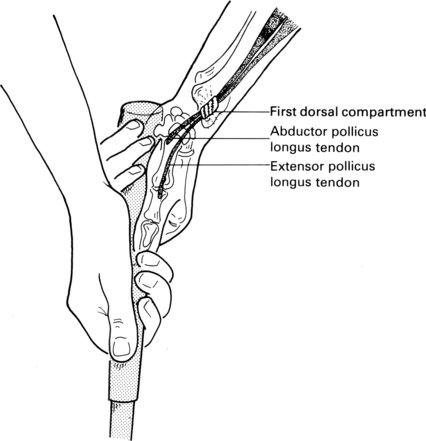

De Quervain’s disease (also known as Hoffmann’s disease) is an inflammation and thickening of the synovial lining of the common sheath of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons (Figure 19.5).

Figure 19.5 De Quervain’s disease (example). Reproduced, with permission, from Clinical Practice of Sports Injury Prevention and Care: Olympic Encyclopaedia of Sports Medicine, Volume V. Renstrom, P.A., F., H., (1994).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree