Chapter 13

Wheelchair seating

This chapter outlines some of the key features of wheelchairs and cushions which need to be considered when this equipment is selected and adjusted for patients. The first section provides an overview of wheelchair cushions with particular emphasis on the effects of upright sitting on pressure distribution. The second section summarizes different types of wheelchairs and the effects of wheelchair set-up on mobility, stability and pressure. Those who require more information are well advised to refer to the excellent books solely devoted to this topic.1–3

Wheelchair cushions

It is important that patients sit on appropriate cushions to prevent pressure ulcers. A poorly fitted, maintained or prescribed cushion or a cushion placed upside down or around the wrong way can cause debilitating pressure ulcers necessitating months of bedrest. The soft tissues overlying the ischial tuberosities are most vulnerable to damage from sitting and cushions are primarily designed to protect these areas (see Chapter 1 for discussion on causes and management of pressure ulcers).

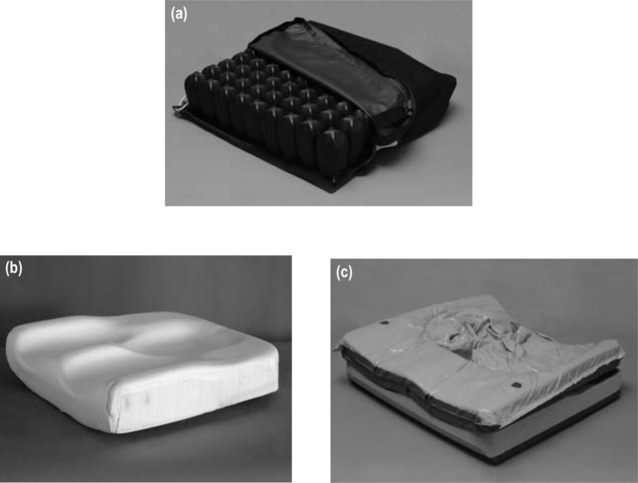

Most of the commercially-available cushions are air-, foam- or gel-based (see Figure 13.1a–c).4 A recent Cochrane systematic review found insufficient evidence to recommend one type of cushion over another, suggesting that decisions about appropriate cushions for patients need to be based on rationale and clinical reasoning and cannot yet be based on good quality evidence.5 Often a cushion which provides adequate pressure relief for one patient will be inappropriate for another. This is partly because the pressure-relieving features of cushions are influenced by many factors, including the wheelchair and its set-up, and patients’ mobility, skin integrity, nutrition and weight. Cushions need to be prescribed on a case-by-case basis after examining their effects on pressure distribution.

The pressure-relieving qualities of cushions need to be assessed every time a new cushion is trialled. This can be done using simple or sophisticated equipment to measure skin-interface pressures.4,6–8 These pressures are measured with patients sitting on their cushions in their wheelchairs. However, there is not one critical pressure below which patients will be safe from skin damage and above which they will not. The appropriate pressure is determined by patients’ susceptibility to pressure ulcers and their ability to relieve pressure.2 However, as a general rule, peak pressures over vulnerable sites should be kept well below 60 mm Hg.4,7,9,10

The pressure-relieving qualities of cushions should also be assessed by examining skin integrity immediately after patients return to bed following a period of sitting in their wheelchairs. When a new cushion is trialled, patients should only sit for between 30 minutes and 1 hour. The length of time spent sitting can be gradually increased but the skin should continue to be checked after patients return to bed and always checked at least once a day. If the skin looks red and does not blanch with localized pressure, the cushion is not providing adequate protection.5 Either the cushion needs to be modified or changed, or the length of time spent sitting needs to be reduced. Alternatively, pressure needs to be more effectively or frequently relieved when sitting, or the set-up of the wheelchair needs to be changed.

Air-based cushions

Air-based cushions relieve pressure by distributing air from pockets of high pressure to pockets of low pressure. In this way, they mould to the shape of patients and distribute pressure over a larger surface area.5 The ischial tuberosities should submerge into the cushion but should not press hard up against the seat of the wheelchair. The effectiveness of air-based cushions is dependent on appropriate inflation. An under-inflated cushion provides little or no protection because the ischial tuberosities bury through the cushion onto the hard seat of the wheelchair. An over-inflated cushion prevents submersion and mimics the effects of sitting on a hard seat. Therapists can use their fingers to crudely check the inflation of air-based cushions by ensuring there is enough room to slide two fingers between the ischial tuberosities and seat. Insufficient space for the fingers indicates that the cushion is under-inflated.

Some air-based cushions are power operated, cycling air between different compartments. They constantly vary pressure, avoiding long periods of high pressure in any one spot.5 These types of cushions are primarily used for patients in power wheelchairs with ongoing pressure problems.

Gel-based cushions

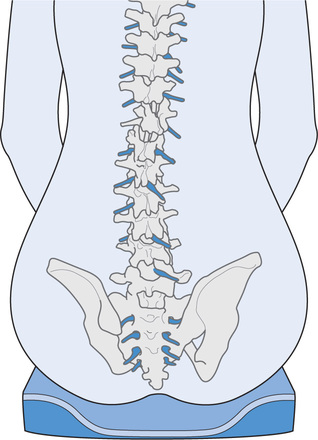

Gel-based cushions work on a similar principle to air-based cushions. They dissipate pressure by allowing gel to move from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. Most have a contoured foam base upon which the gel sits.4 The foam base has a specially-designed hollow or ‘well’ for the ischial tuberosities (see Figure 13.2). This helps ensure that most pressure is borne by the soft tissues over the lateral aspect of the thighs, leaving the ischial tuberosities free to submerge within the gel-filled well. Needless to say, if the well is too wide both the lateral thighs and ischial tuberosities fall into it with a high risk of the ischial tuberosities burying through the gel, pressing up hard against the base of the cushion or wheelchair.

Other considerations

Ease of maintenance

Effect on seating stability, mobility and posture

The choice of an appropriate cushion is also determined by its effect on stability, mobility and posture.11 Some patients feel unstable on air-based cushions and prefer the rigidity provided by foam- or gel-based cushions. More rigid cushions are also easier to transfer from because the cushion does not compress under the hands and patients do not lose height on the vertical lift of the transfer. Transferring from cushions with deep wells can be difficult if patients struggle to get their buttocks up and out of the well.

Cushions also influence seating posture.11 For example, foam can be strategically placed on cushions to prevent legs falling into abduction or sweeping to one side. Similarly, foam can be used to lift one side of the pelvis for patients with a tendency to sit asymmetrically. However, it can be difficult to attain optimal seating posture while also ensuring sufficient pressure protection, especially in patients with deformities and complex seating and skin problems. To improve seating posture it is often necessary to increase pressure over vulnerable bony prominences. The solution is the best possible seating posture which provides adequate pressure protection. It is advisable to compromise on posture before compromising on pressure protection. Foam- and gel-based cushions generally provide greater potential to correct posture but air-based cushions provide greater skin protection.

Cost considerations

The cost of cushions is variable but foam-based cushions are usually the cheapest. The cost can be prohibitive, particularly for those in developing countries and those with limited financial resources. In third world countries, cushions can be cheaply made with a sharp knife, an appropriate piece of foam and some initial training.2,12,13 Alternatively, bicycle inner-tubes can be bound together to create an air-based cushion.1 Cushions made in this way are not ideal but they provide some skin protection and are a better option than sitting directly on the hard base of a wheelchair.

Manual wheelchairs

Wheelchair prescription not only involves finding the appropriate product but also ensuring it is appropriately fitted and set up for the patient. For example, a poorly fitted wheelchair which is too narrow for a patient can cause skin breakdown, and an excessively ‘tippy’ wheelchair can cause a backward fall (see Chapter 4).Most wheelchairs have substantial adjustability, although highly specialized sports wheelchairs do not.

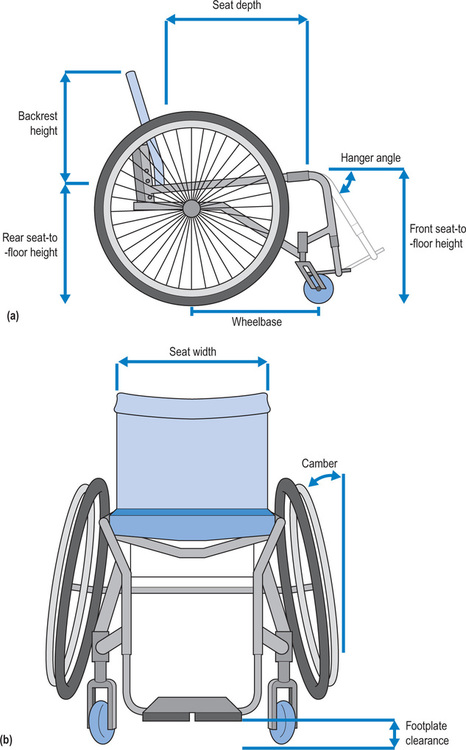

Below is an overview of some of the key issues which need to be considered for fitting, setting up and choosing a manual wheelchair. Several generic issues are equally relevant to power wheelchairs and will be briefly discussed at the end of the chapter.1–3,14,15

Type of frame

There are two types of wheelchair frames, rigid (see Figure 13.3a) or folding (see Figure 13.3b). Rigid frames are primarily prescribed for active patients. They are generally lighter, sturdier, more adjustable and easier to push. Folding fames are better suited to ambulating patients because the footrests can be lifted when standing up. Folding frames are also used by patients who rely on car hoists to stow their wheelchairs on the roofs of cars. However, folding frames are more likely to break and do not always provide a comfortable ride. Some wheelchairs are fitted with suspension to provide a smoother ride; however, suspension is expensive and increases the weight of the wheelchair.

Seat

The seat of a wheelchair can be either flexible (sling) or rigid. Most manual wheelchairs have sling seats because they are lighter and enable the wheelchair to be readily collapsed. However, sling seats often sag with time and, depending on the rigidity of the cushion, can create skin and postural problems. This problem can be overcome by placing a rigid but removable base on a sling seat. Alternatively, the tension of some sling seats can be adjusted, with similar mechanisms used to change the tension of sling backrests (see Figure 13.7).

Seat-to-floor height

The seat-to-floor height determines the overall height of the wheelchair (see Figure 13.4). The back of the seat is usually lower than the front of the seat; consequently, the seat-to-floor height at the rear of the wheelchair is usually less than the seat-to-floor height at the front of the wheelchair. Seat-to-floor height is varied primarily to accommodate heel-to-knee length and to ensure adequate footplate clearance. Taller patients generally require higher seats. However, if the seat is too high, patients are unable to get their knees under tables. They may also have problems with head clearance when sitting in wheelchair-accessible vans. A high seat is also less stable than a low seat, increasing the risk of tipping. In contrast, if patients are short and the seat is low, they cannot comfortably rest and use their arms on the top of a table. A seat which is inappropriately low for a patient raises the knees, concentrating pressure under the pelvis. Patients propelling wheelchairs with their feet require a low seat to enable the feet to touch the ground.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree