Chapter 10 What Makes a Good Clinical Teacher?

[There are] two situations from my own clinical experience as a student: we had two clinical experiences back to back. [In] the first one I went to my clinical instructor was wonderful, top-notch; [in] the second one I did not enjoy [the] clinical instructor. I learned from both of them, things I want to do [as a CI] and things I try not to do.1(p 5)

It wasn’t necessarily her clinical skills that made me think she was such a good clinical instructor. I do think she had very good clinical skills but [they weren’t] the key; it was more her personal skills. She treated me as a peer. She found learning opportunities for me, but she treated me as a peer in front of patients, in front of other staff members, in front of physicians, nurses, other team players. She gave me feedback and the confidence to continue with what I was doing [during an evaluation]. She had a lot of qualities … she was very thorough and she was very dedicated to her patients; she was a strong patient advocate. So some of those skills have affected me in positive ways as a clinician, but you also need those skills with a student. She was dedicated to my learning and she was very thorough and thoughtful with my own learning.1(p 6)

That experience was in contrast to her less-positive memories of the second CI:

She also shared a particularly uncomfortable event that occurred when she was working with this CI:

We were in front of a patient, dealing with an upper extremity [problem] of some sort, and he asked me what I thought was a very strange question: “What is the key to the upper extremity?” And it was just a very strange question in my mind. I didn’t know the answer so he said: “Well, you better go home and think about that.” [It was] in front of the patient and [it] kind of made me feel like I don’t know what I’m doing. The answer he was looking for was the clavicle because it’s the only bony connection to the upper extremities, but it was just his choice of wording and [the fact that] he didn’t rephrase the question. He didn’t offer any additional information; he just kind of left it that vague. Again, in front of the patient.1(p 7)

On my first day my CI welcomed me and gave me a very good impression. After having my last CI it made me appreciate it even more because it was completely opposite. She was just really—she made me feel relaxed right away. Then we started going over some things: the whole environment was completely foreign to me so I had no idea about anything. [She] helped me with that. She sat down with me and went through all that we needed to know in little bits and … let me know that I wasn’t going to learn it all in one day, that it was going to take some time. She was a confidence booster right away. She’s like “I know you’re going to be great. I know you’re going to be fine. So don’t even worry about it.” She had a really good attitude about everything and that just kind of set the theme for the rest of the clinical. Right away I felt comfortable with her. I knew I could ask questions, I knew she wasn’t going to make me feel stupid or anything like that. [It] was really good from the start.2(p 2)

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe some characteristics and attributes of clinical instructors who have been identified as outstanding clinical teachers by their students and colleagues.

2. Discuss the relationships between a CI’s teaching philosophy, teaching “style,” and teaching behaviors and techniques.

3. Identify one exemplar that was a pivotal moment in the reader’s own development as a CI or student and share the exemplar in a narrative form with a colleague.

4. Explore and clarify the reader’s own beliefs about teaching and student learning in clinical environments; begin to articulate the reader’s own clinical teaching philosophy based on those beliefs.

5. Craft a personal vision of what it means to be a good clinical teacher and develop a plan to assist the reader in achieving that vision.

Introduction

As the authors of several chapters in this handbook have clearly indicated, clinical education is a critical component of professional preparation and education for physical therapists at both the entry-level and postprofessional level (see Chapters 8, 9, 11, and 16). In the United States, the clinical education portion of the curriculum currently comprises more than 20% of the professional preparation program on average, and the trend has been toward increasing the length and amount of clinical education experience over the past few years.3 Central to learning in clinical environments are the relationship and interaction between the student physical therapist or physical therapist assistant and the clinical instructor (CI) (or instructors) who provide supervision and guidance during clinical experiences. Although many studies4–13 and several documents14–16 have suggested desirable characteristics, attributes, professional behaviors, and teaching and clinical skills of physical therapy clinical instructors, only a handful have sought to describe expert or exemplary clinic instruction using qualitative approaches to inquiry17–25 and exploring the perspectives and contextualized stories of both CIs and students.

In my own experience as a Director of Clinical Education for decades, there has been ample evidence of a wide variation in student experiences with clinical instructors; many students report tremendously positive experiences with CIs who facilitated their learning and development as future therapists, whereas others report experiences with CIs that were detrimental to their learning. Of greatest interest to me for the study I share in this chapter was the profound and positive impact on learning and development that students who have worked with exceptional CIs report. The landmark work of Jensen and colleagues26–28 on expertise in physical therapy practice and some of my own inquiry into clinical mastery29,30 spurred my interest in further exploring expertise in clinical instruction through the perspectives and voices of outstanding clinical instructors and physical therapist students with whom they have worked.

The broad purposes of the investigation were to undertake the following:

• Explore the professional learning and development of physical therapists who have been recognized as outstanding clinical teachers.

• Elucidate the nature and sources of their beliefs about teaching and learning in clinical settings.

• Describe the characteristics, attributes, and instructional practices of exceptional CIs from the perspective of those instructors and their students.

• Generate rich narrative descriptions of clinical teaching and learning to guide development of preliminary theory about expertise in clinical teaching and student learning in physical therapy clinical settings.

Some guiding questions for this investigation are shown in Box 10-1.

Box 10-1 Guiding Questions for the Investigation of Good Clinical Teaching Practices

Findings: the voice of outstanding clinical instructors

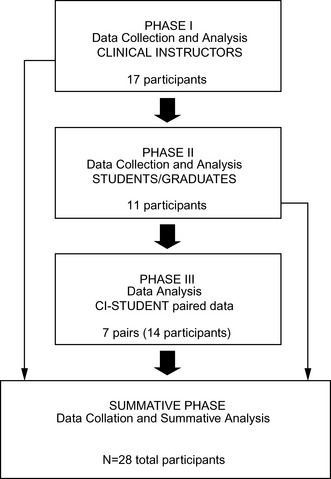

The findings from phase 1 of the study (Figure 10-1) are discussed in the following section through the words and stories of these exemplary clinical teachers. (Please refer to Appendices 10–A to 10–C and Tables A2–1 and A2–2 for further detail about the study design, methods and participants.31–38 The results have been broken down into two broad categories according to the type of data collection method involved:

Resume sort

Most Influential Activities

Professional Memberships and Activities

One of the CIs described what he hoped to instill in his students:

[T]hat it’s not a matter of just coming to work and being a physical therapist, it’s being involved in your Association and the importance [it] has on our profession. With respect to being a clinical instructor, it’s trying to pass that on to students and helping them to value being a member, exposing them to different aspects of membership.39(p 3)

The CI went on to describe how he had traveled to a state legislative committee meeting the previous evening with one of his students so that they could “see the, not just social aspects of it, but the professional benefits too. Just getting everyone else’s perspectives and things like that. I hope that what she saw there was how exciting it is to be able to network with people outside of your direct work environment.”39(p 3)

Formal Educational Preparation

That was one of the most foundational points for me and I think it’s a multi-faceted sort of reason for it. [That’s] where I had my identity as a student. I remember working with both good CIs and CIs that I didn’t think were so good…. I’ve never felt like I ever lost that feeling that I had the first time I went into a clinic…. I realize this is a real critical time in developing into a professional when you are a student. And I think it had lasting implications for me.40(p 1)

Work Experiences

Two CIs explain how their professional work experiences helped them develop professionally:

• I’ve had the pleasure of working with people that have had a significant amount of clinical experience and you can’t help but absorb their most valuable types of treatments, their ways of educating patients, their ways of educating students. I think it’s really accelerated my learning being around skilled clinicians.41(p 2)

• The other thing that I thought was a significant … piece of the puzzle is the environment that I work in because I get support from the manager and from the staff to implement [student] programs and to take time to do it. Without it I couldn’t do what I do now with clinical education.40(p 2)

Somewhat Influential Activities

Continuing Education

The activities identified as “somewhat influential” were a variety of continuing education activities that most CIs saw as essential to keeping current for their practice but not as most influential in their learning and development as a CI. Thus, these CIs suggested that their knowledge of practice, what in the literature on knowledge in teaching might be called “subject matter or content knowledge,”42 was important, but it was only one of several dimensions or domains of knowledge that contributed to good teaching.

Community Service and Honors and Awards

• You try to do the best job you can, but then when you get something like this, it’s like WOW! I’ve been recognized for something you really like to do and that makes you strive to do even better.43(p 2)

• It’s the recognition…. I take away some sense of giving back and helping people through their education (by being a CI.) But … it was nice to be recognized for my efforts being that I do care about these future PTs and the profession.41(p 3)

Clinical instructor interviews

Exemplars

Description of exemplars as an interview strategy has been used in several studies of expertise.26,28,31–33 The CIs in this study were asked to share one or two exemplars; they were urged to “tell me the story” or to “replay the video” of that event (see Appendix 10-B.). As forecast earlier, by far the most frequently shared exemplars were descriptions of experiences as physical therapy students working with CIs. In roughly half of the cases, the experiences were positive, and the CIs purposely sought to emulate the characteristics, commitments, and behaviors of that CI in their own clinical teaching. The negative experiences, which made up the other half of the experiences reported, defined what the CIs did not want to be (or become) for their students.

I had a situation when I was a student where this CI, I think, was on a mission to flunk me. It was strange I don’t know where it was coming from…. She just wasn’t open. If she had a concern it was all top secret you know. She wasn’t really telling me what she was looking for or what the problems were. It was sort of like a CIA kind of thing. I never knew. I was always walking on eggshells and when you’re a student your confidence is kind of flighty and she was harming that for sure. Maybe that was just her method, but I wasn’t responding well to it. So I never forgot it.44(p 9)

Luckily one of the other therapists there saved me. She saw what was happening and took me over and I never forgot that. She realized that what was happening was not kosher. So that experience has stayed with me.44(p 9)

These experiences have been translated into the CI’s current teaching style. This instructor felt it was important “to have it [expectations] all on the table. My goal is to be an advocate and to create a great experience but also to meet expectations that are there from the school and from our facility … but to be helpful and to gently pull people to a higher level.44(p 9)

A more positive experience with a CI was described by another participant:

It was my first rotation in my final year. My CI believed very heavily in education; [she] would take me aside and we would go through a lab in a sense—a practice lab—of what was coming up with the next patient. She was very, very energetic, a lot of fun, and I enjoyed [the labs] because it took the pressure off…. She was never condescending to me; it was always ‘well, yeah, that will work [the way the student suggested], but maybe try this.’ [She was] letting me choose and letting me make my mistakes without jumping on me.45(p 5)

The CI speaking here has purposefully attempted to emulate the enthusiasm for teaching, the respect for students, and the scaffolding for learning that was demonstrated by his memorable CI many years prior.

In one instance, a CI described an experience with her most difficult student:

When I think about my whole career being a CI and having students, there’s one student that comes to mind … it was the most difficult student I had and one in which the student did not succeed. It was a real challenge for me…. But I was determined to make this work. As a CI I thought, I can do this. I have a challenging student and that’s okay. And what do I need to do to make this work. And so for me it was a good experience.46(p 5)

For this CI, working with this student who didn’t succeed was a “good experience” because she was forced to re-examine approaches to teaching and strategies that had previously worked for her with other students. She explored the student’s learning needs and tried to adapt her teaching to best meet those needs. And, despite the fact that the student was not successful in the end, she felt the kind of deliberate reflection she engaged in about the student’s learning and her teaching had transformed her as a teacher. She felt she had expanded the repertoire of approaches that she could employ for the variety of students she might encounter in her continued work as a CI.

The exemplars described by this sample of CIs are consistent with the findings of David Irby years ago in his studies of distinguished medical educators.47,48 As Irby writes of his excellent clinical teachers: “They acquired their knowledge of teaching primarily from the experience of being a learner (the apprenticeship of observation of good and bad examples) and a teacher (reflecting on what worked and did not work).”49(p 339) In a later study of clinical teachers in medicine, Pinsky and Irby49 found that good teachers used the experience of failure to improve their teaching. They did so by using failure as a catalyst for several forms of reflection:

• Reflection on action involved assessing their teaching after a perceived failure.

• Reflection for action (anticipatory reflection) involved planning for future teaching in light of past experience.

• Reflection in action involved assessing and trying to adapt teaching in the moment in the context of a teaching/learning activity that did not seem to be going well.

Similar forms of reflection were also reported by Buccieri and associates18 based on a study with a small sample of expert physical therapist clinical instructors. These findings also resonate with a large body of research on teacher thinking summarized by Clark and Peterson50 and Clark.51 The experienced teachers those authors describe engage in intentional, interactive, improvisational and reflective thinking about their teaching: “They reflect on and analyze the apparent effects of their own teaching and apply the results of these reflections to their future plans and actions. In short, they have become researchers on their own teaching effectiveness.”50(p 292)

Influential People

Teachers and Professional Colleagues

In the category of teachers, 11 participants identified academic faculty members who served as professional role models for them as both clinicians and clinical educators. These academic faculty members were almost universally described, as shown in Box 10-2.

Box 10-2 Characteristics, Attributes, and Behaviors of Individuals with Positive Influence

One CI described how an academic faculty member influenced his approaches to clinical teaching:

He influenced … how I think, how I critically analyze. If I go to a course, I’m not going to believe it just because they tell me [it is correct]. Same thing with a research article … just because it’s there, I’m going to look for the flaws in it and how that might influence whether I can use that [information] clinically or not. He modeled evidence-based practice long before it became cliché.52(p 7)

Thus, the CI today reports a commitment to assisting his students to incorporate this type of critical analysis into their learning experience with him: “I want them to know why they are doing a particular technique, not just [do it] because it was shown to them.”52(p 8)

As discussed earlier, other teachers who were very influential in the learning and development of these CIs were clinical faculty members: their CIs when they were students. The characteristics, attributes, and behaviors of CIs that were viewed as positive influences for the CIs who participated in the study are shown in Box 10-2. Most of the CIs indicated that they seek to emulate many of these attributes and behaviors in their work with students.

• CIs not sharing or making expectations clear

• Supervision at the shoulder during the entire experience

• A disrespectful or condescending attitude toward the student

• Public humiliation of the student (in front of patients caregivers or colleagues)

I had an instructor who would not leave me ever, ever, to the point where they would sit right next to me and write things down as I was doing things. I even had to say once, ‘Do you have to be right there?’ ‘Well, yeah.’ And so I said I would never make my students that uncomfortable…. I said that I would never, ever be that way with my students.43(p 4)

Eleven of the 17 CIs also identified professional colleagues as powerful role models and mentors for them as both clinicians and CIs in their respective communities of practice.20,53,54 As you might expect, and as has been borne out by these findings, the professional identities of “clinician” and “clinical educator” are interwoven in the view of the CIs in this sample. The most frequently described characteristics, attributes, and behaviors of these professional colleagues and mentors are listed in Box 10-2 and mimic those in the previous two categories of clinicians.

One CI describing two colleagues who had been mentors to her put it this way: “They showed me that you didn’t have to be an 8 to 5 PT. There was much more to it than managing your caseload. There is that personal side. That’s how I practice. I don’t practice by the numbers and things like that; I practice by the people.”43(p 5)

Students

The students themselves were influential for the CIs involved in the study. All of the CIs reported that they learned something from every student they had worked with, from excellent students to very challenging students. The common refrain was “the experience works both ways” or “it’s just a great two way street.”55(p 8) Here is one description from a CI who has worked with numerous students for more than 12 years: “Every student is a teacher. I learn something from every student that I have. It sort of all molds together … the more students I have, the more I learn about them and teaching.40(p 8) This same CI went on to report that the students he learns most from are those that provide him with honest feedback on his performance as a CI, which he genuinely appreciated. He also remarked on how the wide spectrum and diversity of students he has worked with require him to constantly “reconfigure my (his) approach” according to the student’s learning needs.

I think a lot of my students bring as much to the clinical as what I can give back to them … and I always make it a point to say that to them. ‘Don’t be afraid to express or inform us of those things that you’ve learned along the way because I feel the clinical education experience works both ways. You don’t come here and I just give you all this knowledge and then you leave. I like to see the interaction back and forth because there are always things that you can teach me. I’m not the all-knowing wise one here. I know what I know, but you also know what you know, so it works both ways.56(p 8)

Patients

Finally, influential people for these CIs included the patients they have worked with throughout their careers. They saw their relationship with patients as similar to that with students in some ways; that is, the relationship is one that involves reciprocal teaching and learning, partnering, mutual respect, and mutual responsibility. As one CI stated: “As therapists we are teachers … and healing and learning are joint efforts.”45(p 8) The CIs reported that they translate the lessons learned from their patients over the years into their encounters and teaching with students. Such lessons included the importance of respectful interaction, using people first language, treating the patient as a person as a whole versus a body part, obtaining informed consent, being an active listener, and being patient: “I want the student to be respectful to every patient they see and know that they are not a body part or a problem; they’re a person. I want them to evaluate the whole body, the whole person, not just a knee.”52(p 9)

I treated an English professor years ago. He kept overhearing PTs refer to their patients as the ‘shoulder lady’ or the ‘guy with the knee.’ He was recovering from a tibial fracture and wanted to be referred to as the ‘guy who will ski again’ rather than a ‘tibial fracture.’ What this taught me is that how we label patients could have a substantial effect on their view of themselves, how we treat them, and perhaps their outcomes.57(p11)

Beliefs about Student Learning and Clinical Teaching

When asked about how they felt students learn best, the CI’s responses merged with another question about the type of environment that enhances learning. The recurring themes in response to these questions are shown in Box 10-3.

Box 10-3 Facilitators and Impediments to Student Learning from Clinical Instructors’ Perspective

One quote from a CI captures many of the facilitative elements mentioned in Box 10-3:

I think the best environment for a student is one where they are kept busy but not overly busy … where they have that hands-on experience but with support. Where they have an opportunity and a comfort zone to talk to the CI frequently if need be and not feel like they are left out on a limb to struggle…. I don’t want to come across as a know-it-all because I’m not. I want to make them feel like it’s okay for them to come and talk to me—that it’s not a bother for me. That’s why I’m there working with them.45(p 10)

As you might expect, when CIs were asked to share their beliefs about what factors might impede or constrain student learning, their descriptions tended to be on the opposite end of the continuum from those factors identified earlier in this section. Impediments or barriers to learning included, first and foremost, student fear and discomfort in the view of these CIs. The sources of fear and discomfort could be from the environment itself (the demands of today’s health care system), the CI, other staff, or the student (see Box 10-3). Note how they contrast with perceived facilitators of student learning.

I will ask questions of the student, but if they don’t look like they are on the same page, I’ll hold most of our discussion until we are in a private setting…. I’m not a drill sergeant-type of clinical instructor. If they are right on with their responses, then the questions will continue. And if they’re drawing a blank, I’ll bring them out of the treatment setting and we’ll talk about it…. I won’t continue to grill them if they’re just not there. Maybe change the direction of the questioning, but definitely not continue to fluster them. You hate to have them come up with the wrong answers in front of the patient. That just isn’t good for either party.58(pp 7, 9)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree