Chapter 4 Physical Therapy Education In The Digital Age

Leveraging Technologies to Promote Learning

The Educational Environment in the Digital Age: The Contemporary Student

National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers and Administrators

Learning Research and its Implications for Educational Technology

Educational Technology Integration: Selection, Implementation, and Evaluation

Privacy and Digital Citizenship

Scholarly Investigation of Technology Integration

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe a framework for selection of educational technology resources to facilitate and inspire student learning.

2. Describe processes for implementation of educational technologies in the face-to-face and virtual teaching environments.

3. Discuss the benefits and limitations of educational technologies in promoting student learning.

4. Discuss implications of cognitive load theory, situated learning, and learning engagement research for the use of educational technologies.

5. Describe the components of digital citizenship and the importance of including digital citizenship as part of health professions education.

6. Describe contemporary educational technologies and alignment with desired learning activities.

7. Describe opportunities for developing scholarship investigating student learning and the use of educational technologies.

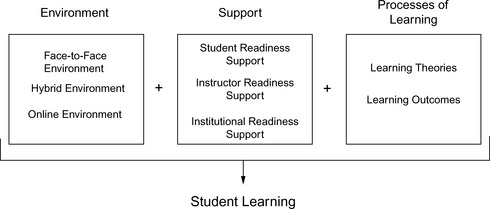

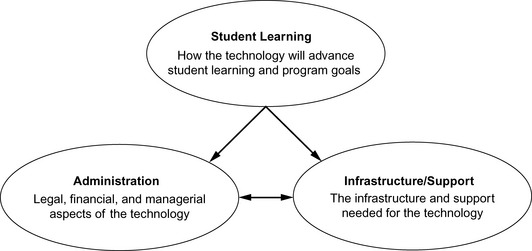

The purpose of this chapter is to provide some theoretical foundation and practical advice for the selection, implementation, and evaluation of educational technologies within the context of traditional face-to-face, blended (combining face-to-face and online teaching), and online physical therapy education. Although the degree of technology integration varies across these learning environments, the core elements required to achieve student learning do not change. To engage the technology in a meaningful way, the use of technology must be shaped by learning theory and learning outcomes and supported by readiness on the part of the students, instructor, and institution (Figure 4-1). Implementing technology without these critical elements results in superficial use of technology, wasting the time, talent, and treasure of students, instructors, and the institution.

In the 10-plus years since the release of the second edition of The Handbook of Teaching for Physical Therapists, significant changes have occurred in the educational technology landscape. What was then new, innovative, and exciting is now part of the smorgasbord of learning resources expected by students. Digital presentation slides, posting of course materials online for 24 × 7 access, and the ability to use mobile devices inside and outside of class to access learning resources are part of the tapestry of teaching and learning tools students expect to be available.1 Electronic books, new mobile devices, augmented reality, game-based learning, gesture-based computing, and learning analytics are some of the near-term and longer-term technologies expected to play a role in the educational setting.2 To keep pace with these changes, the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) has rewritten its definition for educational technology. For the purposes of this chapter, AECT’s updated definition will be used, “Educational technology is the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technologic processes and resources.”3

The educational environment in the digital age: the contemporary student

A visit to any campus in the United States illustrates students’ frequent use of technology. The omnipresence of cell phones, mobile computers, and iPod devices demonstrates the degree to which students have integrated technology into the routines of daily life. The most recent survey of student technology use conducted by the Educause Center for Applied Research (ECAR)2 paints a profile of contemporary student use of technology for personal and educational purposes. Of the nearly 37,000 respondents, 89% indicated they own a laptop, nearly 63% have an Internet-capable handheld device, 94% use a library website regularly, and almost 80% use a learning management system at least weekly.

Regarding students’ perceptions of educational technology, most students report using technology makes completion of course activities more convenient and positively impacts their learning; however, less than third believe the use of technology leads to more active engagement in courses.2 Although students’ use of technology in their personal lives seems to be ever present, they prefer a moderate amount of technology use in course activities. Perhaps this dichotomy is explained by students’ perceptions of faculty’s ability to use technology effectively. Forty-seven percent of students believe faculty use technology effectively, 49% think faculty have adequate preparation for using technology, and students report only 38% of faculty members provide adequate preparation for students to use course technology.2,4

Much has been written about factors that determine faculty adoption of educational technologies. Availability of support personnel, incentive structure, workload, technology and infrastructure reliability, training, and peer experiences are factors generally cited as determinates of adoption.5,6 A key variable underpinning all these factors is the notion of digital natives and digital immigrants.7 Students are generally digital natives, individuals who have grown up using technology; technology was present when they were born and they have used a variety of technology in many aspects of their lives. On the other hand, faculty tend to fall within the category of digital immigrants—those who were born in the predigital technology era and have assimilated into the digital teaching and learning landscape. Does this difference in digital status explain the variances in technology use rate between students and faculty? To what degree should use of technology be part of the physical therapy curricula? These questions are explored further in the following sections of this chapter.

National educational technology standards for teachers and administrators

The importance of technology fluency for faculty and students in the current educational environment is evident. To maximize the time, talent, and treasure invested in the use of technology, instructors and administrators must be prepared to make informed decisions in the selection and use of digital learning resources. Created by the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), the National Educational Technology Standards (NETS) are intended to serve as a guide for professional development of teachers and administrators in the use of educational technology.8 NETS for teachersa are designed to provide a framework for the effective use of technology to advance student learning. NETS for administratorsb are designed to define what administrators need to know and be able to do in order to fulfil their responsibility as leaders in the effective use of technology in educational settings. Faculty members and administrators are encouraged to incorporate the NETS into annual professional development plans as a means to keep student learning as the centerpiece of all instructional activities while adopting technology-rich educational environments. A listing of the NETS are found in Appendices 4-A (teachers) and 4-B (administrators).

Learning research and its implications for educational technology

Technology and student learning

The ability of technology use to directly impact student learning has been debated for decades. Some researchers argue that any change in student learning accompanying the introduction of technology can be attributed to the changes in instructional methods that occurred as a result of the introduction of technology, the novelty of the technology and therefore increased student interest, or more thoughtful design of the instruction.9–11 Others suggest that, if the interactive nature of learning is taken into consideration, the use of technology can affect how something is learned. Therefore, the use of technology can, to some degree, have a direct connection to student learning.12–15 As the debate continues among educational researchers, most acknowledge that technology is a permanent and ever-changing fixture in the teaching and learning environment; therefore, employing instructional design principles to ensure the effective integration of technology-infused instructional methods is crucial. Revisiting Dr. Carter’s and Dr. Martinez’s course may serve as an example.

Cognitive load and multimedia learning

Human working memory serves as a temporary storage and processing facility for new information. The capacity of working memory is limited to managing about seven elements of information at any given time. As information is processed and moved into long-term memory, it is filed away for permanent storage and on-demand retrieval. Learning complex information or tasks can be improved by employing instructional design strategies, which effectively manage working memory and long-term memory capabilities.16

Cognitive load theory focuses on the capacity and role of working memory in processing information.16 This theory suggests that cognitive load, or mental processing, is affected by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic cognitive load occurs as a result of the nature of the information being presented. For example, a problem requiring students to simultaneously process several elements would result in a high demand on working memory. Extrinsic cognitive load is determined by the way in which information is presented—the learning environment, instructional strategies, and design and quality of instructional materials. Using both text and images and placing them on separate pages requiring learners to constantly shift their focus between the text and images is an example of extrinsic cognitive load. Embedding the text directly in the image decreases extrinsic cognitive load and therefore expands working memory resources for other tasks.

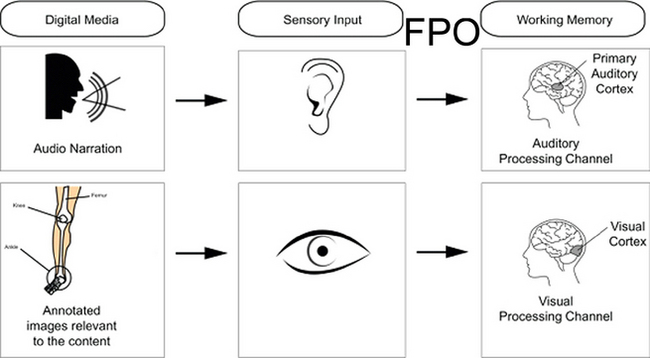

The limited processing capacity of working memory is further explicated by the notion of separate channels for processing of auditory and visual information.17 Each channel is limited in the amount of information that can be processed at any given moment (Figure 4-2); therefore, presenting the same information both visually and verbally does not make effective use of working memory—both channels are processing the same information. Learning can be increased by presenting complementary information visually and auditory.

The cognitive theory of multimedia learning was developed by applying cognitive load theory and the notion of dual channel processing to the use of digital media in educational environments.18,19 This theory suggests instruction should be designed such that:

1. Only a single input of information per working memory channel (auditory or visual) is used,

2. Only relevant information is included, avoiding the use of decorative images and extraneous information, and

3. Words and graphics are included in the instructional materials.

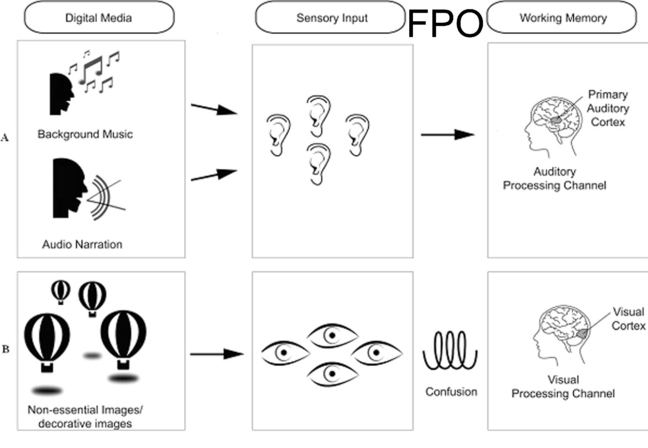

Including unrelated information in one sensory channel is an inefficient manner of teaching; it can confuse the learner (Figure 4-3).

In summary, when designing digital media to support student learning:

• Use graphics and words to present information.

• Use only graphics and words essential for student learning.

• Place explanatory text directly next to or embedded in the graphic.

• Use audio to explain animations.

• Avoid extraneous sounds (e.g., background music).

• Avoid extraneous images (e.g., “fun” or decorative pictures not essential to understanding the content).

Student engagement and the use of educational technologies

Chickering and Gamson’s Seven Principles for Good Undergraduate Education,20 first published in 1987 and based on decades of research about student learning, provides a basic set of guidelines for engaging students in the learning process. Although originally proposed for undergraduate education, the principles apply equally well to graduate and professional education. The availability of educational technologies provides opportunities to operationalize the seven principles in new and different ways.21 Table 4–1 summarizes these principles and provides examples of ways in which technologies can be used to implement the principles.

Table 4–1 Using Technology to Implement the Seven Principles

| Principle: Summary | Potential Benefit of Using Technology | Examples of Activities and Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Engage students reluctant to speak during class. Increase access to faculty members. Ease communication for non-native English speakers. | Increase access to the instructor outside of class via the use of e-mail, text chat, or discussion boards. Use web conferencing to offer tutoring sessions during times convenient for students and instructors without requiring travel to campus. | |

| Increase time available for collaboration. Ease communication for non-native English speakers. | Study groups and project collaboration can be accomplished by using electronic white boards contained in web-conferencing solutions or via virtual collaborative work spaces such as Google Docs. E-mail, discussion boards, text chat, and social networking tools can also provide avenues for collaboration. | |

| Increase opportunities for learning by doing and synchronous or asynchronous interactions. | Search for information using electronic databases available online via libraries or other resources. Increase access to experts in the profession through the use of web conferencing and discussion boards. Use virtual simulation environments to practice the application of new knowledge or skills. Provide opportunities for practice and formative feedback via self-grading electronic quizzes and practice examinations. | |

| Increase timeliness and frequency of feedback opportunities. Increase ease of providing feedback. | Electronic submission of assignments and use of electronic portfolios increase the flexibility of time and space for practice (students) and feedback (instructor). Video captures of students’ performance and use of video-commenting tools can provide opportunities for the student to review his/her own performance, for others to review and provide feedback, and for longitudinal review of performance. Screen-capture software provides the opportunity to quickly create mini tutorials and easily distribute them to multiple students. | |

| Increase efficiency of studying and ease of access to learning materials. | Recording lectures, tutorials, and instructional resources using lecture capture or podcasting and posting them online allows students to decrease the time spent commuting to campus, gives them the ability to review the materials when needed, and affords them the opportunity to shape their study time in a manner most beneficial to their learning needs. Shifting time and space for lectures and first exposure to information to outside of the classroom by recording lectures increases class time available for focused engagement in learning activities. Increase efficiency of study time by providing online access to study materials via the library or through the learning management system. | |

| Increases ease of providing formative feedback on drafts of assignment responses. Increases ability to provide multiple examples of high-quality work. | Collaborative work spaces such as Google Docs allow instructors or peers to provide feedback on draft of papers and presentations. Exemplars of completed assignments posted in the learning management system provide students examples of high-quality work. | |

| Increases ability for students to represent their knowledge and skill in multiple formats. Provides multiple practice opportunities for students. | Multiple practice opportunities can be made available by posting lectures in the learning management system, creating practice quizzes and exams with automated feedback, using electronic flashcards. Using presentation software, inexpensive and easy-to-use video recorders, and freely available graphic creation and editing software presents the opportunity for students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills in a variety of ways. |

Data from Allen IE, Seaman J. Class differences: online education in the United States 2010. Available at: http://sloanconsortium.org/sites/default/files/class_differences.pdf; Accessed 22.05.2011.

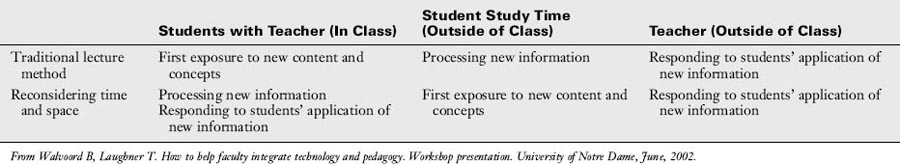

Educational technologies afford instructors the opportunity to apply the seven principles as well as to reconsider the configuration of time and space for teaching and learning and increase student engagement.22 Traditionally, students’ first exposure to instructional content is in the classroom in the form of a lecture. Although students are often assigned readings to complete before class, the reality is that many (if not most) do not complete the readings, or do so at a very superficial level. Therefore, instructors find themselves spending class time lecturing, time they had planned to devote to learning activities. Technology allows us to shift the first exposure to content and concepts from inside to outside of the classroom, holding students accountable for completing the first exposure activities and thus allowing more in class time for applying the new information. Therefore, the application of new concepts occurs in the presence of the expert, the instructor, instead of outside of class, when students are separated by time and space from the content expert. Table 4–2 illustrates this notion of reconceptualizing the time and space for teaching and learning.

Revisiting Dr. Martinez’s plans for Dr. Carter’s course serves to illustrate this notion of shifting time and space. Her plans to combine prerecorded mini lectures and assigned readings for students to complete before class will prepare students for applying the information during in class discussions and learning activities. By adding a quiz or assigning a short summary of the key points to be completed before class, or at the beginning of class, Dr. Martinez’s students are held accountable for completing the preclass activities. These accountability activities will also highlight gaps in students’ understanding of the content, which Dr. Carter can address with a mini lecture or short discussion during class. As a result most class time can be spent helping students apply the new concepts. Sometimes referred to as just-in-time teaching,22 this model of leveraging technology increases the time students have with the content expert to process new information.

Educational technology integration: selection, implementation, and evaluation

Selection

Employing an intentional and outcomes-driven process to select technology can increase the chances of finding the right solution that is strategic and focused on supporting instructional methods to advance student learning. Resources for purchasing and supporting educational technologies should only be expended if they help to achieve the program’s goals and objectives. Fragmented, inefficient, and ineffective efforts, wasting the time and energy of instructors and students, may result if factors other than learning outcomes drive technology selection. Figure 4-4 summarizes the key elements of educational technology selection.23

Six basic steps are employed to ensure that each technology selection element is considered (Table 4–3):

• Step 1: Identify instructional needs

• Step 2: Identify stakeholders

• Step 3: Develop selection criteria

• Step 4: Identify potential technologies

• Step 5: Determine the total cost of ownership (TCO)

Table 4–3 Basic Steps When Considering Technology Selection

| Step | Process |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Identify instructional needs | Define the instructional activity or method and associated learning outcome or program goal the technology is expected to support. Describe what you as an instructor need to do that you cannot do without the technology or can do better with technology. |

| Step 2: Identify stakeholders | Include stakeholders to represent each of the three elements of educational technology selection: Student learning: Faculty colleagues, clinical preceptors, students, instructional support personnel Administration: Finance/budget personnel, representation from legal services Infrastructure/support: Help-desk, network, and infrastructure support representative |

| Step 3: Develop selection criteria | Selection criteria can be categorized as related to each of the three elements: Student learning: How well the technology appears to support the instructional activities, student learning outcomes, or program goals. How the technology affects cognitive load. How the technology helps facilitate good educational practices (see Table 4-1) Administration: Amount of training and support required for students, instructors, and support personnel; legal terms and conditions; alignment with the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and other relevant regulations. Infrastructure/support: The technology’s ability to run on multiple computing technology platforms (PC or Mac, different versions of operating systems, etc.) and on an average computer, network infrastructure requirements to use the technology, compatibility with existing technology used in the program or on campus, physical environment requirements (space, electrical power, etc.), reported reliability and maintenance time requirements |

| Step 4: Identify potential technologies | The instructor and stakeholders identify solutions to be evaluated using the criteria developed in step 3. |

| Step 5: Determine the total cost of ownership (TCO) | The TCO is calculated for each viable technology solution identified in step 4. TCO includes all costs associated with the implementation of a particular technology, including initial implementation costs and ongoing expenses. TCO calculations typically include: Licensing fees (initial fees and annual renewal if applicable) Maintenance and support fees Hardware and software required to host and run the technology Time spent to train faculty, students, and support personnel Time required to conduct the initial implementation Expected time required to maintain and support the technology |

| Step 6: Select the technology | Using the selection criteria and total cost of ownership information, stakeholders evaluate each of the technology solutions and select the technology that best fits the selection criteria. |

Implementation

As with most endeavors, planning leads to a greater chance for success. Using technology in the educational process is no different. Technology often exists on the periphery of an institution’s instructional programming. Implementation conducted in a piecemeal fashion, perhaps when year-end “extra monies” are available, with little or no long-range plan; is a recipe for disaster. Following the four Cs of implementation maximizes the likelihood of successful technology integration.24

The Four C’s of Implementation

Successful implementation of technology requires four Cs:

1. Comprehensive approach to planning

2. Commitment (of all stakeholders)

3. Collaboration (of all stakeholders)