Chapter 5 Assessing and Improving the Teaching and Learning Processes in Academic Settings

Did you ever express or hear comments like these?

Well, you have to be careful about putting too much time into your teaching. Good teaching takes time away from the things you need to do to get tenure and promotion at this institution. What really matters are research, grant writing, and publications.

Isn’t program assessment the function of the curriculum committee? Besides, I was hired as a neuroscientist, not an educator. I know what the students need to know; that’s why I need one more semester hour in my course to cover the material. Whatever you do, don’t volunteer for the self-study task force; leave those accreditation activities to the educators. Sure, I evaluate my course. All students fill out an evaluation form the last day of class. I have good assessment data for my teaching, just look at my final student grades. They all achieved the learning outcomes as demonstrated by their grades.

Assessment techniques are used to assess one’s teaching with the goal of improving student learning (curriculum) and the overall program. Essentially, there are two types of assessments: student learning outcomes and program effectiveness.1 Assessment helps answer the question, How well do we do what we say we’re going to do? Classroom educators purposefully focus on designing, evaluating, and revising the particular courses they teach. Intent on the subject matter they teach, educators often disconnect their teaching roles from the ongoing assessment and thoughtful scholarship of how their teaching actually influences student knowledge, understanding, attitudes, values, and behaviors. In this chapter, we explore practical mechanisms and tools that all educator-scholars can use for assessment and improvement of their teaching and resultant improvement in student learning.

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define and give examples of the three main learning problems that students experience: amnesia, fantasia, and inertia.

2. Distinguish between assessment and evaluation.

3. Describe the relationships between assessment and student learning across educational settings, including classroom, program, and institution.

4. Identify the four pillars of transformative assessment and describe how and why they undergird program assessment activities.

5. Articulate principles of best practice for assessing student learning, including didactic and clinical student learning and performance, professional behaviors, and clinical reasoning.

6. Recognize the utility of the Teaching Goals Inventory and its relationship with the preactive teaching grid. (See Appendix 5-A.)

7. Describe processes that are intended to improve teaching: classroom assessment techniques (CATs), small group instructional diagnosis (SGID), quality circles, peer coaching, and end of course student ratings.

8. Describe how curriculum mapping can provide an alignment structure for the assessment process.

9. Distinguish between scholarly teaching and scholarship of teaching.

Assessment

The terms evaluation and assessment are often used interchangeably. However, for the purposes of this chapter, we make the following distinction: Evaluation refers to an end point, determining whether an action is right or wrong (e.g., answers to questions on a classroom examination). Assessment refers to looking closely at teaching events with a central emphasis on student learning and considerations of how to improve student outcomes.2

The assessment movement in education has been stimulated at the federal level by both institutional and specialized (professional) accreditation agencies. This movement is having a powerful influence on higher education. The central focus is on accountability of the educational program related to student learning outcomes.2–4 The Association for the Assessment of Learning in Higher Education (AALHE; http://www.aalhe.org) is an organization that focuses on using effective assessment practice for purposes of improving student learning. AALHE offers members opportunities to join in discussions about assessment practices and hosts an annual assessment conference. Publications from the Council on Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA;http://www.chea.org) should be regular reading in physical therapy and physical therapist assistant programs for those interested in assessment. Why is ongoing educational assessment, which helps us determine ways to improve our teaching and resultant student outcomes, so important to physical therapy educators that we allocate an entire chapter to address it? The answer lies in the learning problems students bring with them when they enter physical therapy programs.

Student learning problems

Students come to our physical therapy programs with well-ingrained learning problems that hinder both the acquisition and retention of information. Lee Shulman5 identifies three of these common problems as amnesia, fantasia, and inertia. For those of us teaching the next generation of health care professionals, these problems with student learning are an anathema.

Pillars for transformative learning

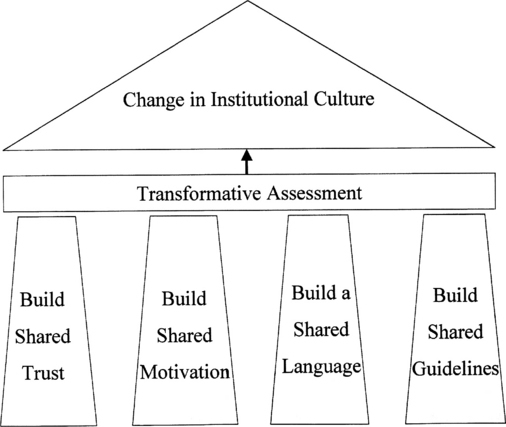

Angelo states, “[D]o assessment as if learning matters most.”6 Assessment affects all levels of education, from individual classrooms and laboratories to programs and the institution in which the programs reside. Angelo argues that there are four essential components, or pillars, for transformative assessment (Figure 5-1). The term transformative is used with specific intent. It means that something actually will happen within an institution that leads to a change in the institutional culture. This change is facilitated through individuals who share common beliefs and values, work together to develop guidelines, and act on those guidelines. An example of transformative change in higher education is the current emphasis on student learning, which is visible in many venues (e.g., highlighted in conference topics, discussed and debated in the research literature, and emphasized in accreditation documents).

Figure 5-1 Angelo’s four pillars of transformative assessment.

(Adapted from Angelo T. Doing academic development as though we value learning most: transformative guidelines from research and practice. In James R, Milton J, Gabb R. Research and Development in Higher Education 22. Melbourne, Victoria: HERDSA, 2000.)

The four pillars for transformative assessment are as follows:

1. Build shared trust. This is done through the faculty’s building a productive learning community in which the faculty involved in assessment trust one another. All persons must feel respected, valued, and safe to share their experiences.

2. Build shared motivation. There have to be collective goals worth working toward and problems worth solving. This means a shift for some faculty because faculty often focus on what they will teach rather than on what students will learn; students, in turn, often focus on getting through the program.

3. Build a shared language. Faculty need to develop a collective understanding of new concepts needed for transformative changes. Although assessment may mean only student course evaluations or standardized testing—and time wasted to some faculty members—a collaborative model would focus on assisting the entire faculty to see the broader conception of assessment that focuses on formative assessments and student learning and successful achievement of program outcomes.

4. Build shared guidelines. Faculty will benefit from a short list of research-based guidelines that can be used for assessment to promote student learning. An example of a research-based guideline in physical therapy or physical therapist assistant education might include gathering formative assessment data on the ability of students to demonstrate critical professional behaviors or ability-based outcomes. For example, do students demonstrate empathy across the curriculum? What evidence do students provide in support of their clinical decision-making skills?

Nine principles of good practice for assessing student learning (Box 5–1) serve as a good starting point for thinking about your current assessment activities.7(p 23) You might want to examine these nine principles and see which of them are included in the assessment activities in your classroom, program, or institution. For example, do your assessment activities attend equally to the teaching-learning experience and the learning outcomes?

Box 5–1 Nine Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning

1. Assessment of student learning begins with educational values.

2. Assessment is most effective when it reflects an understanding of learning as multidimensional, integrated, and revealed in performance over time.

3. Assessment works best when the program has clearly, explicitly stated purposes.

4. Assessment requires equal attention to outcomes and to the experiences that lead to those outcomes.

5. Assessment works best when it is ongoing and not episodic.

6. Assessment fosters wider improvement when representatives from across the educational community are involved.

7. Assessment makes a difference when it begins with issues of use and illuminates questions that people really care about.

8. Assessment is most likely to lead to improvement when it is part of a larger set of conditions that promote change.

9. Through assessment, educators meet responsibilities to students and to the public.

Adapted from AAHE Assessment Forum. Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning. In Maki PL. Assessing for Learning: Building a Sustainable Commitment Across the Institution. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2004.

Assessment of student learning

Classroom Assessment

All of us in higher education, regardless of whether we are in a professional school or a graduate department, aim to produce graduates who achieve the highest possible quality of learning. As educators, our greatest reward is the success of our graduates. As we teach, we are constantly engaged in an “informal” process of classroom assessment—that is, determining what students know, do not know, need to learn, do, and become.9 To do this, we ask students questions, observe and react to body language that depicts confusion or boredom, and listen carefully to students’ comments. In response to this input, we may speed up, slow down, review material, or change in other ways to react to student learning needs.

Angelo and Cross’s well-known classic book on classroom assessment techniques is an excellent resource for faculty.8 This book is a practical guide for designing and implementing classroom assessment techniques for any faculty member, regardless of his or her background. Their model of classroom assessment is built on the following assumptions about teaching and learning: The quality of student learning is directly (not exclusively) related to the quality of the teaching. One of the most promising ways to improve learning is to improve teaching.4,8,9 To improve effectiveness, teachers first must make their goals and objectives explicit and then obtain feedback to determine the extent to which students are achieving such goals. (See the preactive teaching grid in Chapter 2.)

• To improve learning, students need to receive appropriate and focused feedback early and often. They also need to learn how to assess their own learning.

• The type of assessment most likely to lead to improvement of teaching and learning is that conducted by faculty themselves, in which they formulate the questions specific to their own teaching concerns.

• The processes of systematic inquiry are an intellectual challenge and an important source of motivation for faculty. Classroom assessment provides this kind of challenge.

• Classroom assessment does not require specialized training. It can be carried out by any dedicated teacher within any discipline.

• Through collaborating with colleagues and actively involving students in classroom assessment efforts, faculty can enhance learning and personal satisfaction.

Teaching Goals Inventory

A useful way to initiate classroom assessment planning is for each faculty member to complete the Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI).8 The TGI is a questionnaire designed to assist faculty in identifying and ranking the relative importance of their teaching goals for any class. With one particular class in mind, the faculty member rates the importance of 52 teaching goals across six clustered areas: higher-order thinking skills, basic academic success skills, discipline-specific knowledge and skills, liberal arts and academic values, work and career preparation, and personal development. The complete TGI is available in Appendix 5-A. You will see that there are many parallels between the TGI and the philosophical orientations to curriculum discussed in Chapter 2.

Classroom Assessment Techniques

CATs, as proposed by Angelo and Cross, have the following characteristics8:

• The focus is on observing and improving learning rather than on observing and improving teaching.

• The individual teacher decides what and how to assess and how to respond to the information. Autonomy and professional judgment are respected because the teacher is not obligated to share the results of her or his CATs with anyone else.

• Faculty improve their teaching by constantly asking themselves three questions: “What are the essential skills, knowledge and values I am trying to teach? How can I find out whether students are learning these skills? and How can I help students learn better?”9(p 5)

• Student learning is reinforced by doing CATs, as students are asked to reflect on what they are learning, give examples of how to use the information, and indicate points of confusion that can be clarified long before a midterm or final examination.

• As formative assessments with the purpose of improving the quality of student learning, CATs are usually anonymous as well as ungraded. Thus, students can focus on and provide honest feedback about what and how they are learning rather than searching for “the right answer.” Students as well as teachers learn to enjoy CATs as both an intriguing and an intellectual process.

• Each class of students presents with a unique and diverse mix of student backgrounds, learning attitudes and skills, and learning problems, and as such, each class develops a unique microculture. Thus, CATs need to be used sensitively and specifically with each different class being taught. A CAT that is successful for one teacher in one class with one group of students at one time of the year will not necessarily be similarly successful if any one of these variables changes.

• Use of classroom assessments is an ongoing process throughout the semester.

• Minute paper (also known as the “one-minute paper” or “half-sheet response”). Stop your class a few minutes early and have students respond to two questions: (1) What was the most important concept you learned during this class? (2) What important question remains unanswered for you?

• Muddiest point. At the end of class, have students write a brief response to the question, What was the muddiest point in this lecture today?

• Modeling. At any point in the class, have students draw a model that demonstrates the basic relationships among concepts. Have students discuss their models with each other and field their questions.

• Metaphors. Ask students to write a metaphor followed by a one- or two-sentence explanation. This is easily done as a fill-in-the-blank question. For example, the question is “Doing research is like ____________.” The answers—for example, “walking through molasses,” “a puzzle,” “going to the dentist,” and “an adventure”—are very telling.

• Defining features matrix. The purpose of this exercise is to assess students’ skills in categorizing information using a given set of critical defining features. Faculty can then do a quick check of how well students can distinguish between similar concepts and make critical distinctions. This assessment technique is particularly good for helping learners make critical distinctions between apparently similar concepts. Table 5–1 provides an example from a course on health education and an assessment of health behaviors.10

• Documented problem solutions. The aim of this assessment technique is to determine how students solve problems and how they understand and express their problem-solving strategies. This technique is particularly good in helping students to explicate their thought processes and approaches to solving problems. For example, in a biomechanics course, you could divide the class into groups and give each group a problem. Have the groups solve the problem and document each step of the problem-solving process. Then have the groups do a show-and-tell presentation on their problem solution approaches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree