Chapter 16 Post-professional Clinical Residency and Fellowship Education

Clinical Residency and Fellowship Education Today

What are Residency and Fellowship Programs?

Overview of Residency and Fellowship Models

Key Components in the Design of Residency Curricula

Development of Clinical Reasoning in Residency and Fellowship Education

Strategies for Linking Academic and Clinical Curriculum Components

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Discuss the history and philosophy of residency and fellowship education for physical therapists in the United States.

2. Identify key components of residency and fellowship curricula.

3. Compare and contrast residencies and fellowships.

4. Describe various models for design of residency and fellowship educational programs.

5. Discuss learning needs of residents and fellows compared with physical therapy students.

6. Design mentoring strategies to facilitate the development of clinical reasoning skills in residents and fellows.

7. Describe residency and fellowship teaching strategies to facilitate the development of efficient, systematic, patient-centered clinical reasoning skills and provide a rationale for their use.

8. Identify resources that can be used in the design of residency and fellowship curricula.

Clinical residency and fellowship education today

In their desire to attain advanced clinical skills, some therapists seek postprofessional clinical doctorates in physical therapy (DPT degrees), but emphasis on advanced clinical training is highly variable in many existing programs. Others turn to certifications or weekend continuing education courses. Physical therapists, frustrated by a piecemeal approach to weekend continuing education courses, are rethinking their professional goals to establish sound, cohesive, professional plans for themselves—plans that will have a major impact on their level of clinical competence over time.1 Postprofessional clinical residency and fellowship education can assist physical therapists to significantly advance their knowledge and skills in a defined area of clinical practice. The educational principles and teaching strategies presented in this chapter and the resources outlined in Appendix 16-A can assist educational institutions and health care organizations in the design of residency and fellowship curricula and in the development of effective mentoring strategies. The concepts presented are also applicable to aspects of physical therapy professional curricula. Potential applicants to residency and fellowship programs may also use the concepts in this chapter to determine whether the scope and intensity of residency and fellowship education meet their career objectives and may also be used to assess the quality of the programs to which they may wish to apply.

What are residency and fellowship programs?

Mission and philosophy of residency and fellowship education

Although it is difficult to articulate a single mission statement or philosophy that can cross many clinical specialty areas and include a broad range of models, individual residency and fellowship programs should compose a mission statement that fits with their umbrella organization’s mission and the specific program’s core philosophical approach.2,3 In addition, key program outcome objectives should be carefully constructed to help guide the curriculum and to choose effective teaching strategies. Residency and fellowship education is directed toward the development of a therapist’s ability to link theory and practice through a combination of didactic and clinical coursework and through supervised and unsupervised clinical practice. In this chapter, didactic coursework will refer to instruction in the basic and applied sciences (e.g., anatomy, neurophysiology, biomechanics, research methods), whereas clinical coursework will refer to instruction in patient-centered topics and the development of psychomotor skill (e.g., lab practice, case discussion, clinical seminars). Beyond instruction in these areas and refinement of advanced intervention strategies, the core of residency and fellowship curricula is the development of a systematic clinical reasoning process.

Residency and fellowship education is founded on the premise that the development of advanced clinical practice requires a significant commitment of time and practice over an extended period of time. It is also based on the tenet that clinical mentoring involving ongoing, constructive critique and feedback is necessary for the development and refinement of advanced examination and management skills.4–6 Residency and fellowship programs also seek to educate clinicians who will be able to critically review current literature and to creatively integrate relevant evidence into clinical practice. Some programs seek to have their graduates contribute to literature through research. At the foundation of residency and fellowship curricula is the goal to develop clinicians who will substantially advance the practice of physical therapy, provide expertise to the patients they serve, and make lasting contributions to their professional communities through clinical practice, teaching, consultation, and community service.

Residencies versus fellowships

Physical therapists interested in formal postprofessional clinical training with overarching goals of specialization and the development of expertise have two primary options supported by a credentialing process: clinical residencies and clinical fellowships. Neither of these experiences is considered to be synonymous with the term clinical internship, which may refer to any supervised clinical experience. The American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education (ABPTRFE), which determines requirements, policies, and procedures for the credentialing process, proposes the following definition of clinical residencies: “A clinical residency is a planned program of post-professional clinical and didactic education for physical therapists that is designed to significantly advance the physical therapist resident’s preparation as a provider of patient care services in a defined area of clinical practice. It combines opportunity for ongoing clinical supervision and mentoring with a theoretical basis for advanced practice and scientific inquiry.”6

Whereas residency programs are designed to foster initial development of expertise in one of the primary areas of physical therapy practice, fellowships train professionals to advance their skills in a subspecialty area. The primary specialty areas for residency training tend to coincide with the eight board certification areas offered through the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties (ABPTS) (Box 16-1). Because residency training is not required for entry into a fellowship, some individuals may elect to go directly into a fellowship after achieving the experience and coursework required by a particular program. ABPTRFE’s definition of a clinical fellowship is: “… a planned program of post-professional clinical and didactic education for physical therapists who demonstrate clinical expertise, prior to commencing the program, in a learning experience in an area of clinical practice related to the practice focus of the fellowship. (Fellows are frequently post-residency prepared or board-certified specialists).”6

Box 16-1 Primary Physical Therapy Practice Specialty Areas*

Data from American Board of Physical Therapy Specialities: www.abpts.org.

Clinical residencies and fellowships are similar in many respects, including training models that include a didactic curriculum, clinical curriculum, and one-on-one clinical mentoring, but they differ in focus and in the background of their participants. ABPTRFE credentialing requirements and program outcomes also differ somewhat. The important similarities and differences between clinical residencies and fellowships are summarized in Table 16-1.6 For the remainder of this chapter, unless specifically stated, for simplicity the term residency will be used to refer to both types of post-professional training. Similarly, the term resident will refer to the learning needs of a resident or fellow unless otherwise stated.

Table 16-1 Residency and Fellowship Comparison

| Residencies | Fellowships | |

|---|---|---|

| Content area | Physical therapy specialty area (e.g., pediatrics, sports) | Physical therapy subspecialty area (e.g., neonatal care, Division I athletics) |

| Participant characteristics | Typically entry-level or recent graduates; pre-ABPTS board certification | Two to six years of practice experiences7; may be ABPTS board certified and/or residency trained |

| Curricular focus | Based on DSP in specialty area | Based on practice analysis in specialty area (e.g., DASP for OMPT) |

| Credentialing requirements | 1500 total hours Didactic training (minimum, 75 hr) One-on-one clinical mentoring (minimum, 150 hr) | 1000 total hours Didactic training (minimum, 50 hr) One-on-one clinical mentoring (minimum, 100 hr) |

| Length | Minimum, 9 mo (typical range, 9-18 mo) | Minimum, 6 mo (typical range, 6-36 mo) |

| Outcomes | Advanced clinical practice in specialty area; ABPTS certification | Advanced clinical practice in subspecialty area |

ABPTS, American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties; DSP, Description of Specialty Practice; DASP for OMPT, Description of Advanced Specialty Practice for Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapy.

From American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education. Application for Credentialing of Residency and Fellowship Programs. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association Residency and Fellowship Credentialing, 2010.

The credentialing process

In addition to medicine,8 which has had ambulatory care residencies since the early 1870 s, psychology,9 podiatry,10 optometry,11 and pharmacy12 are among the many professions that have recognized the knowledge, clinical competence, and confidence that can be attained through residency education for entry into the profession and for specialization. Each of these professions has established an accreditation or credentialing process for clinical residencies. For physical therapy, the concept of residency training dates back to the 1960s, with the development of the University Affiliated Programs that incorporated formalized, interdisciplinary, long-term training in pediatrics.13 In the late 1970s, the lack of opportunities for advanced training in manual therapy in the United States led some American physical therapists to travel to such countries as Norway and Australia to receive long-term mentoring and advanced coursework.1

In 1993, the American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT) created the Standards for Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapy Residency Education14 and a formal recognition process to assess manual therapy programs. APTA developed a credentialing process for post-professional clinical residencies in 1998 and for fellowship programs in 2000.2,15 The APTA credentialing process merged with the AAOMPT recognition process in 2002 and with the Sports Medicine Section’s process for credentialing sports physical therapy residencies in 2004.2

Since 2000, the number of credentialed residency and fellowship programs in the United States has expanded rapidly. There are now credentialed residency programs in the specialty areas of orthopedics, neurology, pediatrics, sports, geriatrics, women’s health, and cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy. Credentialed fellowship programs now exist in orthopedic manual therapy, hand therapy, movement science, and Division I athletics. In response to demand from the growing number of programs requesting credentialing, support, and continued assessment, in 2009, APTA established the ABPTRFE and the related Credentialing Services Council and Program Services Council.2 The Credentialing Services Council conducts the review of programs, oversees site team visits, and implements training for reviewers and onsite visitors. The Program Services Council promotes the development of additional residency and fellowship programs by developing resources and marketing plans to increase awareness of residency and fellowship education.2

The credentialing process for new residency and fellowship programs ensures a level of consistency among programs and guarantees a high-quality experience for participants. The process requires programs to submit a formal application and receive an onsite visit by residency education experts. Among other elements, the application requires programs to develop a program mission statement, outcome objectives, formal didactic and clinical curricula, a clinical mentoring plan, and formal assessment plan for participants. During the site visit, the program’s director, faculty, clinical facilities, and other resources are examined. APTA offers extensive supporting material and short courses to support individuals and facilities who are either in the credentialing process or considering development of a residency or fellowship. Refer to Appendix 16-A for a compilation of resources.

Overview of residency and fellowship models

A variety of residency models exist in the United States today, which can all meet the requirements of credentialing. Some of the options, which are highlighted in Table 16-2, include the following:

• Employment offered through the sponsoring organization or tuition based

• Affiliated with a university or residing in a hospital system or private practice

Table 16-2 Overview of Common Residency and Fellowship Models

| Characteristic | Options (Any Combination of Characteristics Is Possible) | |

|---|---|---|

| Full vs. part time | Full-time: Curriculum is continuous, linear Typically 9-18 months Patient care 20-30 hr/wk within normal work week Participants reside at program’s home location | Part-time: Curriculum may be blocked in short segments May take longer to complete Participants probably not employed by sponsoring institution Participants may travel for instruction and mentoring |

| Employment | Employment through sponsoring institution: Compensation based on hourly rate for patient care or percentage of regular starting salary | Tuition based: Participants pay program for instruction provided and continue to work outside of program |

| Affiliation | University affiliated: Program housed in university setting where entry-level physical therapy education program exists Graduate credit may be offered toward post-professional clinical doctorate or other graduate degree | Hospital system or private practice affiliated Program housed in hospital system or private practice Programs may contract with universities to provide some didactic content to residents |

Full-time versus part-time models

In a full-time model, residents complete the residency in a continuous, linear fashion, working and learning around a normal work week. In contrast, part-time models often allow residents to live at a distance from the program’s home location. The resident must then travel regularly to a designated residency clinic during weekdays, evenings, or weekends to receive instruction, provide patient care, and receive one-on-one clinical mentoring. As a result of the less linear structure, part-time residencies are highly variable in duration. In either format, ABPTRFE requires that both residency and fellowship programs be completed in a maximum of 36 months.2

Key components in the design of residency curricula

Descriptions of specialty practice

The APTA credentialing process requires residency programs to demonstrate that curricula reflect practice dimensions identified through a valid and reliable practice analysis.2 All of the clinical practice areas for which residencies or fellowships have been developed are based on a document called the Description of Specialty Practice (DSP), Description of Advanced Clinical Practice (DACP), or Description of Advanced Specialty Practice (DASP). The document is used to both guide the curriculum and ground the credentialing process. Resources for obtaining existing DSPs are included in Appendix 16-A. The DSP of the specialty area should provide the framework for determining the major curricular components of the program (e.g., examination, evaluation, diagnosis). Practice dimensions of the DSP, which are stated in behavioral terms, can be used to define the performance outcomes of the program and instructional objectives in individual courses.

Curricular structure

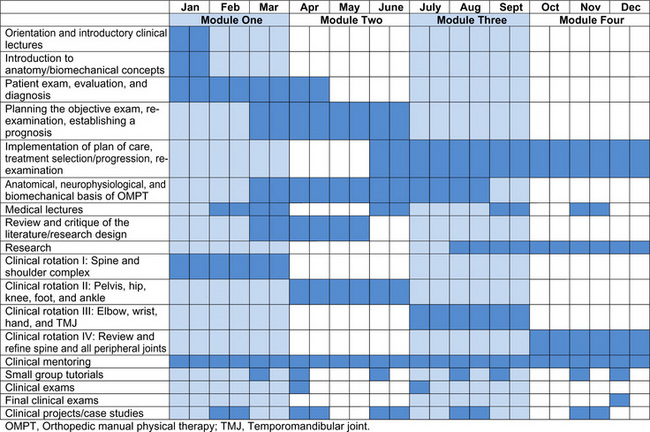

The grid presented in Figure 16-1 provides a temporal illustration of the curriculum of a year-long, full-time fellowship program in Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapy (OMPT) based in a hospital system. Although the actual content would differ, the curriculum components and design in this example can apply to other clinical specialty areas.

The program is divided into four teaching modules, which are reflected in Figure 16-1. OMPT clinical lectures and laboratory instruction are presented during a 1-week introductory intensive to establish a foundation for examination and treatment in the clinic. Selected anatomy and biomechanical lectures are also presented during the initial week and during periodic lectures over the first 4 months of the program, from January through April. Clinical coursework and laboratory instruction occur about 2 to 3 weekends each month and cover the major curricular topics shown in Figure 16-1 (e.g., planning the objective examination, re-examination, implementation of plan of care, and medical lectures). Clinical practice in an outpatient clinic and clinical supervision begin the second week of the program and continue throughout the program. Small group tutorials focused on refinement of clinical reasoning concepts, review and critique of the literature, case study review, and handling skills are held about every 3 weeks during nonclinic days. Clinical examinations occur at the end of every module.

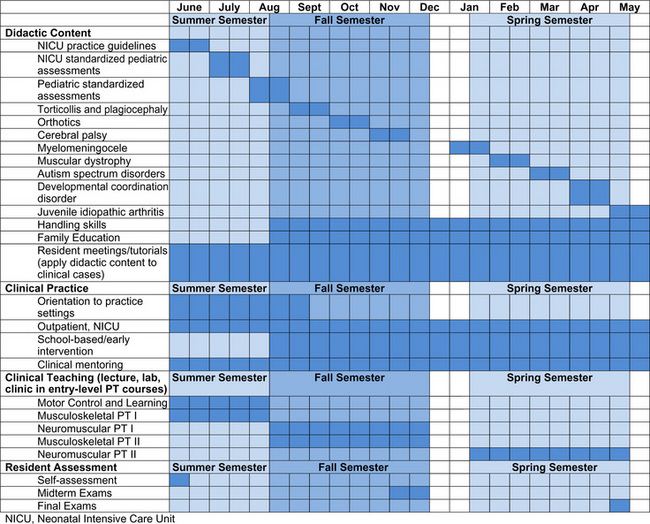

An example of the curricular layout for a year-long, full-time pediatric residency program housed in a university setting is provided in Figure 16-2. The concepts described previously for the OMPT curriculum still apply, but note the differences in content and in structure with a program using a university calendar as its basis. The clinical teaching component is also different, giving the resident opportunities to learn through preparation and execution of teaching experiences. The resident’s responsibilities for teaching gradually build throughout the year from primarily assisting faculty early on to eventually planning and leading class sessions and laboratories at the end of the year.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree