1 What is a stroke?

Definition of a stroke

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is suddenly interrupted, thus depriving the affected part of the brain of oxygen and glucose which are both vital for its normal functioning. This may cause wide-ranging neurological deficits (see also chapter 3).

Stroke is defined as ‘a clinical syndrome characterised by rapidly developing clinical symptoms and/or signs of focal, and at times, global (applied to patients in deep coma and those with subarachnoid haemorrhage), loss of cerebral function with symptoms lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin’ (Hatano 1976):

• ‘Focal loss of cerebral function’ means that a specific area of the brain has been affected. ‘Global’ applies to patients in deep coma and those with subarachnoid haemorrhage.

• ‘With no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin’ means that other conditions mimicking stroke have been excluded or are not thought to be likely.

Types of stroke

Ischaemic stroke

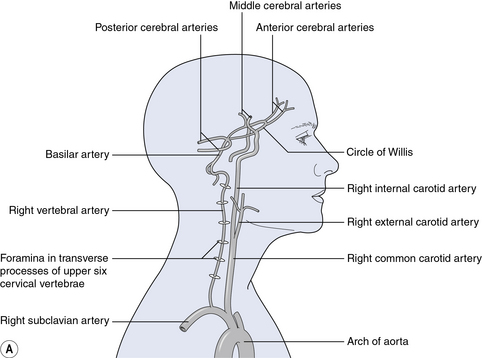

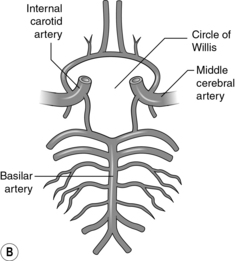

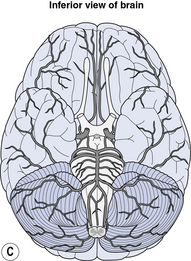

Ischaemic strokes account for about 80% of strokes and are due to a blockage or reduction in the blood supply to part of the brain. (See Figure 1.1 for detailed diagrams showing the blood supply to the brain). There are several mechanisms:

• Thrombosis formation on larger intracranial vessels, e.g. middle cerebral artery

• Embolism of a blood clot in the heart, aortic arch and carotid, i.e. a blood clot ‘travels’ to the brain and blocks an artery in the brain.

• Intrinsic small vessel disease (which usually affects the small deep arteries in the brain)

• Haemodynamic causes, e.g. hypotension may cause cerebral hypoperfusion (decreased blood flow to the brain) and this may lead to so-called ‘watershed infarcts’

• Other less common causes, e.g. vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels), intravenous drug abuse, carotid artery or vertebral artery dissection (a tear in the artery which allows blood to enter the wall of the artery and split its layers), coagulopathy (any defect in the blood’s clotting process), venous infarction (caused by blockage of a vein in the brain), migraine.

Haemorrhagic stroke

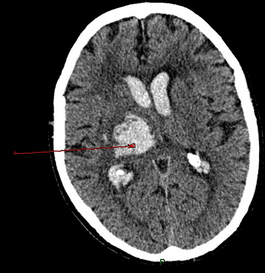

Haemorrhagic strokes account for about 15% of strokes and are due to bleeding in the brain. Sometimes the bleeding is from an anatomically abnormal blood vessel in the brain, e.g. arteriovenous malformation, intracranial aneurysm, or from a tumour. Sometimes the cause of bleeding is uncertain and the bleeding is attributed to presumed abnormalities in smaller blood vessels, e.g. hypertensive vessel disease, amyloid angiopathy (where amyloid, a sort of protein, forms in a blood vessel wall in the brain). Patients with abnormal blood clotting, including those taking anticoagulants such as warfarin, are also more likely to suffer haemorrhagic strokes. Determining the underlying cause of haemorrhage in individual patients can be difficult, and is a subject of ongoing research. An example of an intracerebral bleed is shown in Figure 1.2.

Differentiating between ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke

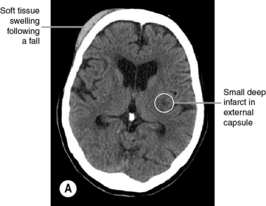

It is essential to differentiate ischaemic from haemorrhagic stroke as this dictates treatment. For example, in the acute phase, thrombolysis (‘clot busting’) and aspirin can be administered to patients with ischaemic (but not haemorrhagic) strokes. The only reliable method to differentiate between the two main types of stroke is to perform brain imaging. On brain computed tomography (CT), acute haemorrhages always show up as a white area (Fig. 1.2), though over the subsequent few days the haemorrhage gradually darkens and may become indistinguishable from a cerebral infarct (Wardlaw et al. 2003). Signs of ischaemic stroke on CT include brain swelling, hypodensity (darker area) and occasionally a blood clot in one of the cerebral arteries. Some patients with ischaemic stroke have a normal CT scan, particularly if they are scanned very early after onset of symptoms.

The scans shown in Figure 1.3 are typical from patients with ischaemic stroke. When interpreting a scan, one has to imagine looking up from the feet, so the left side of the brain is on the right hand side of the image. The front part of the brain is at the top of the image, and the back of the brain is at the bottom of the image. The scanner moves from the top of the head down to the cervical spine, and creates a series of ‘slices‘of brain images.

Transient ischaemic attacks

Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) are defined as ’sudden onset of focal neurological disturbance, assumed to be vascular in origin’ lasting for less than 24 hours (Hatano 1976). In practice, most TIAs last for less than an hour. They are almost always due to short-lived episodes of cerebral ischaemia which resolve spontaneously. The risk factors for TIAs are very similar to the risk factors for ischaemic strokes. A TIA is a ‘warning’ sign that the person is at high risk from a stroke, and needs to be referred for urgent medical assessment.

Impact of stroke

Stroke is the third most common cause of death and the commonest cause of disability. In the UK, there are 150 000 new strokes per year (Office of National Statistics 2001).

Incidence

‘Incidence’ is a measure of the risk of developing some new condition within a specified period of time. Stroke incidence has been falling in recent years, at least in the developed world. In Oxfordshire in the early 1980s, the incidence of stroke was around 2 in 1000 people per year (Bamford et al. 1988). Twenty years later, the incidence of stroke had fallen by 29% (Rothwell et al. 2004). This was attributed to better prevention of a first-ever stroke, e.g. by the more widespread use of blood pressure lowering medication (for high blood pressure) and statins (to reduce cholesterol) and is in spite of an increase in the number of older people in the population.

Stroke is a global problem. Estimates of the incidence of stroke in different parts of the world vary depending on how ‘cases’ of stroke are identified (Feigin 2007). It is clear, though, that stroke incidence increases with age; in a review of 15 stroke incidence studies in the developed world, the rate of stroke in those aged <45 years ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 per 1000 person-years, whilst for those aged 75–84 years, the range was 12 to 20 per 1000 person-years. In terms of premature deaths and years of life lost, stroke is a greater problem in low-income and middle-income countries (Strong et al. 2007).

Prevalence

Prevalence is a measure of the total number of cases of disease in a population. The prevalence of stroke increases with age. For people over the age of 65, the number with a stroke ranges from 46 to 73 per 1000 population; in other words, around 1 in 20 people over the age of 65 may be living with the effects of stroke (Feigin et al. 2003). This represents the number of people who could potentially benefit from the provision of Exercise after Stroke services.

Cost of stroke to the nation

A recent UK study estimated that the cost of treatment and loss of productivity arising from stroke amounted to a total societal cost of £8.9 billion a year, with treatment costs accounting for approximately 5% of total UK National Health Service costs (Saka et al. 2009). The financial cost of stroke includes many different components; the main ones in the first year of stroke are the costs of acute hospitalisation, inpatient rehabilitation and nursing home care (Dewey et al. 2001). Indirect costs, which were defined as the time lost from productive activity, made up 6% of the costs. Other costs include the cost of re-hospitalisation for recurrent stroke, medication, community rehabilitation, respite care and investigations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree