11 Evaluating exercise and fitness training after stroke

outcome assessment

Introduction

Previous chapters discussed the preparation, design and delivery of exercise programmes for stroke survivors. In this chapter, we will focus on outcome assessment to determine the impact of such programmes. Some of the measures used in outcome assessment may be similar to those used for screening stroke survivors prior to referral for exercise (chapter 9), but the purpose of using measures for outcome assessment is distinctly different.

Defining measurement and assessment

First of all, we need to define what we mean by ‘assessment’ and another term with which it is often used interchangeably, i.e. ‘measurement’ (Wade 1992). There are many definitions of both terms. Kondraske (1989) proposed the following:

Let’s take the example of the Timed Up-and-Go (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991), a test that measures how long it takes to rise from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn round and sit down (see Table 11.1). Determining the time taken to complete the test involves actual measurement, whereas deciding how the result compares with healthy people of the same age and sex involves assessment. Thus, according to the definitions above, the process of assessment involves an additional element of judgement.

Assessment: why?

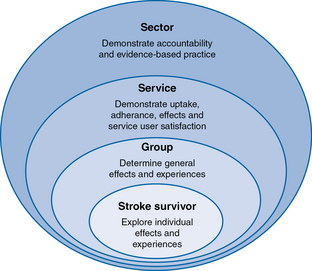

As mentioned in the Introduction, outcome assessment is undertaken to provide feedback to stroke survivors, exercise professionals, service managers and commissioners, about the impact of the service. Outcome assessment can be considered at different levels of analysis, as illustrated in Figure 11.1:

• At the level of the individual stroke survivor: outcome assessment may involve collecting quantitative information on the effects of exercise. This may include indicators of improved fitness and function, reduced pain or fatigue, the extent to which personal goals have been achieved, and/or qualitative information about their experiences of the service. Information about fitness improvements may well serve to motivate the stroke survivor to continue to exercise and encourage self-management of exercise, as explained in chapter 6.

• At the level of a group of stroke survivors: data can be compiled from individuals to yield information on changes between the start and end of an exercise programme for a whole cohort.

• At the level of a local exercise service: outcome assessment could comprise information on uptake and adherence, effects and adverse events, stroke survivor satisfaction, as well as data on the costs of running the service. Such information demonstrates the impact of the service and may be crucial in justifying the need for the service and hence for funding.

• At the level of a whole service sector: data from local services could be compiled to yield information about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an entire service sector for a particular region, country or organisation (e.g. national charity organisation) – provided that standardised assessment procedures are used. This information can also be used by the sector to demonstrate accountability and evidence-based practice, and the extent to which the service meets user needs.

Assessment: what?

Relevance

Before choosing an outcome measure, it is important to clarify what one wants to know. In principle, it is possible to gather a plethora of information, as Table 11.1 suggests, but just collecting data for its own sake is unethical. One should always start by asking ‘What do I need to know?’, ‘What does this information tell me?’ and ‘What am I going to do with the data?’ In other words: What is the question?

If the purpose of outcome assessment is to assess the extent to which an individual stroke survivor has attained their exercise goals, we need to have a clear understanding of what these goals are and how to measure them. Chapter 10 explained that the general aims of health-related exercise and fitness training after stroke are to improve cardiovascular/cardiorespiratory endurance, muscle strength and endurance, as well as flexibility, motor skills and coordination. In addition, the individual stroke survivor is likely to have their own goals. It may be useful to bear in mind that stroke survivors are more likely to formulate their goals in terms of activities of daily living (e.g. wanting to get up from a chair more easily), general function (e.g. wanting to feel less tired when shopping), or even in more general terms (e.g. wanting to get back to normal) than in terms of specific impairments (e.g. muscle weakness or maximum oxygen uptake) (Lawler et al. 1999). The challenge for the exercise professional is to analyse the stroke survivor’s goals and judiciously choose one or more outcome measures that reflect these goals, while bearing in mind that the measures also need to be scientifically robust.

The International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) as a framework

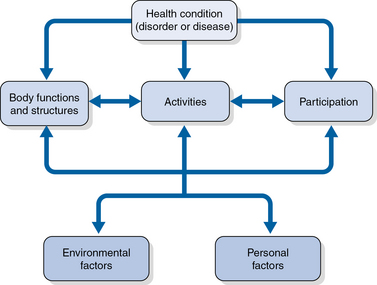

How does an exercise professional decide which outcome measure to use? A framework that may help to clarify matters is the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, or ICF (WHO 2001). The ICF is an international scientific framework that describes and explains different aspects of health and factors that influence health. It can also be used to identify and categorise measures that capture different aspects of a health condition.

Let us use ‘stroke’ as an example of a health condition to explain the ICF model, which is presented in Figure 11.2.

Fig 11.2 Diagrammatic overview of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO 2001). See text for details.

Body functions, structures and impairments

Body structures are anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components, such as joints, muscles and nerves. Impairments are defined as problems in body function or structure such as a significant deviation or loss. Chapter 3 described how a stroke can impair a wide range of functions, e.g. muscle activation or sensation of the affected side of the body, visual perception and attention. The corresponding impairments are paresis, reduced sensation, visual agnosia and hemi-inattention, respectively. As described in chapter 4, many stroke survivors also have a number of fitness-related impairments, including reduced cardiovascular and muscle endurance, muscle power and strength.

Environmental and personal factors

Environmental factors make up the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live. For example, attitudes towards disability at work are likely to influence a stroke survivor’s opportunities for returning to work. Lack of accessible transport may make it difficult for stroke survivors to attend community leisure services (Rimmer et al. 2008).

Personal factors are related to the particular background of an individual’s life (e.g. age, race, education, coping styles). For example, one study suggested that greater use of avoidance coping strategies (e.g. sleeping more than usual or refusing to believe that one has had a stroke) early after stroke was predictive of post-stroke depression (King et al. 2002).

Having presented an outline of the ICF, let us explore how this framework may assist in clarifying the domains represented by outcome measures in the context of exercise after stroke. Table 11.1 lists the various fitness components as categorised by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM 2010), as well as other constructs that may be relevant for assessing the effects of exercise after stroke. These are tabled alongside examples of possible outcome measures and their corresponding ICF domain(s). It is important to emphasise that this table is not exhaustive but rather an overview of a range of options for outcome assessment. From this, one could choose one or more measures that are relevant and appropriate to the individual(s) and the context in which the assessment is to take place.

Table 11.1 Examples of outcome measures for evaluating the effects of exercise and fitness training after stroke and their corresponding ICF domain(s)

| Fitness component | Example of outcome measure | ICF domain |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular endurance | (Maximum) cycling work rate Gait economy Maximum VO2 uptake Respiratory exchange ratio | Body structure and function |

| Body composition | Body mass index Body circumference Skinfold measures | Body structure and function |

| Muscle strength | Upper limb: grip and pinch force Lower limb: isometric or dynamic ankle, knee and hip flexor and extensor force | Body structure and function |

| Endurance | 6-minute walk test (Eng et al. 2002, Fitts and Guthrie 1995, Guyatt 1985, Steffen 2002, Wade 1992, Willenheimer and Erhardt 2000) | Body structure and function |

| Flexibility | Passive and/or active joint range of movement | Body structure and function |

| Agility | Biomechanical gait parameters (e.g. stride length, stance symmetry, contact time, maximum vertical ground reaction force) Timed up-and-go (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991, Steffen et al. 2002) | Body structure and function |

| Coordination | Fugl-Meyer test of physical performance after stroke (Fugl-Meyer et al. 1975) | Body structure and function Activity |

| Balance | Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al. 1989) Tinetti (Tinetti et al. 1986) | Activity |

| Power | Explosive lower limb extensor power | Body structure and function |

| Reaction time | Dependent on the task: time between a cue to a specific action and the start of the action | Body structure and function Activity |

| Speed | 10-minute walk test (Duncan et al. 2007, Wade 1992) | Body structure and function Activity |

| Construct | Example of outcome measure | ICF domain |

| Goal attainment | Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al. 1998) Goal Attainment Scaling (Turner-Stokes 2009) | Body structure and function Activity Participation, depending on the goal |

| Independence in self-care and mobility | Barthel Index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965) | Activity |

| Independence in physical functioning | Functional Independence Measure (Granger et al. 1993), comprising function (i.e. self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication and social cognition) and cognition (i.e. social interaction, problem-solving and memory) Functional Ambulation Category (Collen et al. 1990, Holden et al. 1984, 1986) | Activity Participation |

| Self-reported stroke impact | Stroke Impact Scale (Duncan et al. 2003a,b), comprising physical strength, hand function, activities of daily living, mobility, mood and control of emotions, thinking and memory, communication, participation, stroke recovery | Body structure and function Activity Participation |

| Health status | Medical Outcomes Study Short Form SF-36 (Ware and Sherbourne 1992), comprising physical functioning, role limitations –physical, bodily pain, social functioning, general mental health, role limitations – emotional, vitality, and general health perceptions | Body structure and function Activity Participation |

| Pain | Visual Analogue Scale (Bond and Pilowsky 1996, Price et al. 1999) | Body structure and function Activity Participation, depending on the aspect of pain being examined |

| Mood: anxiety and depression | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith 1983) | Personal factor |

VO2, oxygen utilisation.

Chapter 9 mentioned exercise testing in the context of pre-exercise assessment. Exercise testing with open circuit spirometry may also be used to evaluate fitness outcomes over the course of an exercise programme (Ivey et al. 2011). It is important that the risks involved with exercise testing on a treadmill or bicycle are carefully assessed, as many stroke survivors do not have the required balance or strength for conventional treadmill testing. For an overview of validated protocols for exercise testing, readers are referred to Ivey et al. (2011). Further detailed information about stroke-related outcome measures can be found in Salter et al. (2010) while fitness-related outcome measures are described in the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines (ACSM 2010).

Table 11.1 might suggest that outcome measures neatly fit into distinct ICF domains. In reality, however, the boundaries between different ICF domains may be blurred. For example, the construct of ‘walking’ (e.g. crossing the road) can be seen as a functional activity and therefore difficulties with walking could be interpreted as an activity limitation. However, when we measure walking in terms of biomechanical parameters (e.g. joint displacement or muscle activation), are we still measuring an activity or have we shifted to body function and structure? One could argue that each gait parameter represents a specific body function or structure, and that, by focusing on these, we have lost sight of the functional context in which the ‘walking’ takes place. This example illustrates that there are cases where the same construct may be viewed from different perspectives.

Additionally, some outcome measures comprise items from more than one domain. For example, most items in the Fugl-Meyer test (Fugl-Meyer et al. 1975) evaluate joint movement in specific patterns that have no explicit functional goal, but some items evaluate functional activity (e.g. holding an object). Thus, the majority of the Fugl-Meyer is impairment-orientated, while a small proportion is activity limitation-orientated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree