4 Physical fitness and function after stroke

Physical fitness

Physical fitness is defined by a set of physiological attributes which people have or achieve that relate to the ability to perform and tolerate physical activities. Physical activity describes all body movement produced by skeletal muscle and which substantially increases energy expenditure (USDHHS 2008). Physical activities include work performed during occupational, leisure and sporting activities but also walking, activities of daily living and maintenance of posture.

Components of fitness

The cardiorespiratory system and skeletal muscle constitute the most important physiological systems that define and influence physical fitness. The capacity of these systems is at the centre of the physical fitness concept because they interact to generate external work for all physical activities (USDHHS 2008).

This is why, in this book, we shall focus on aerobic fitness, muscle strength and muscle power:

• Cardiorespiratory fitness (sometimes termed ‘aerobic fitness’) is conferred by the central capacity of the circulatory and respiratory systems to supply oxygen, and the peripheral capacity of skeletal muscle to utilise oxygen. It is commonly assessed by measuring the highest rate of oxygen utilisation ( peak) achievable during maximal exercise. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with the ability to perform and tolerate continuous physical activity, e.g. walking.

peak) achievable during maximal exercise. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with the ability to perform and tolerate continuous physical activity, e.g. walking.

• Muscle power output is defined as the greatest rate of work achieved during a single, fast, resisted contraction. Power output is the product of force and speed of movement, usually reported as a power to body mass ratio (W·kg-1). Power differs from strength in that it is a velocity-dependent characteristic. Strength and power are associated with the ability to lift objects or raise body mass, e.g. mounting a step.

Plasticity of fitness

In healthy people, physical fitness parameters show considerable variation and plasticity that is the ability to change and adapt (Fig. 4.1). Key factors in influencing fitness and plasticity are:

• Age and gender. In adults increasing age causes a decline in cardiorespiratory fitness of 1–2% per year, muscle strength of 1–2%, and muscle power of 3–4% per year (Young 2001). The gender difference accompanying this decline means men have the equivalent of around a 20-year fitness advantage over women. Loss of lean body mass is detectable after the age of 45 years; alongside a gender difference, this may partly explain some of the variation and plasticity (Narici and Maffulli 2010).

• Inactivity. Profound physical inactivity (bed rest) causes a substantial decline in cardiorespiratory fitness (12%), muscle strength (13%) and muscle power (14%) in just 10 days (Kortebein et al. 2008). Thus physical inactivity causes a deconditioning effect on fitness far faster than the effect of ageing.

• Chronic disease. The effects of chronic disease may reduce fitness due to inactivity and secondary consequences such as systemic inflammation (Degens and Alway 2006).

• Activity and exercise. All parameters of physical fitness can be improved by increased physical activity and exercise.

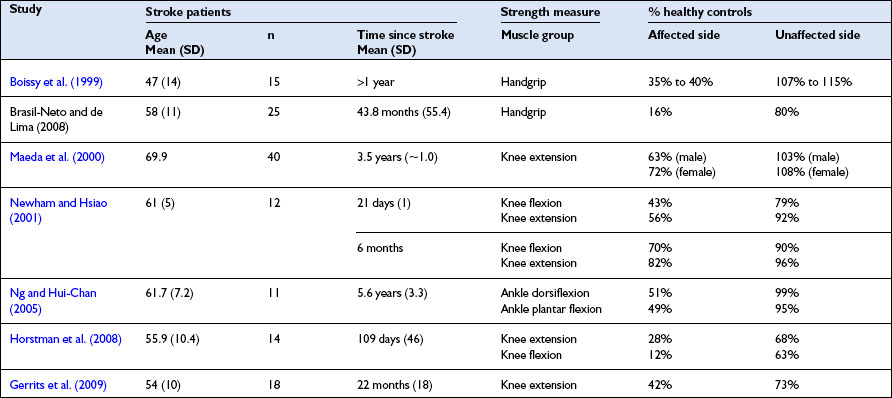

Fig 4.1 Age- and gender-related decline in cardiorespiratory fitness (

l; Shvartz and Reibold 1990) (

l; Shvartz and Reibold 1990) ( *

*

; Malbut et al. 2002) and musculoskeletal fitness (

; Malbut et al. 2002) and musculoskeletal fitness (

l; Skelton et al. 1999) (

l; Skelton et al. 1999) ( *

*

; Skelton et al. 1994) in healthy people aged 50 years and older. Functional thresholds (—) are marked on these data to indicate when low fitness may limit certain activities (Allied Dunbar National Fitness Survey 1992, Ainsworth et al. 2000) or threaten independence (Shephard 2009). Data points are means and error bars represent 2 standard deviations.

; Skelton et al. 1994) in healthy people aged 50 years and older. Functional thresholds (—) are marked on these data to indicate when low fitness may limit certain activities (Allied Dunbar National Fitness Survey 1992, Ainsworth et al. 2000) or threaten independence (Shephard 2009). Data points are means and error bars represent 2 standard deviations.

Functional importance of fitness

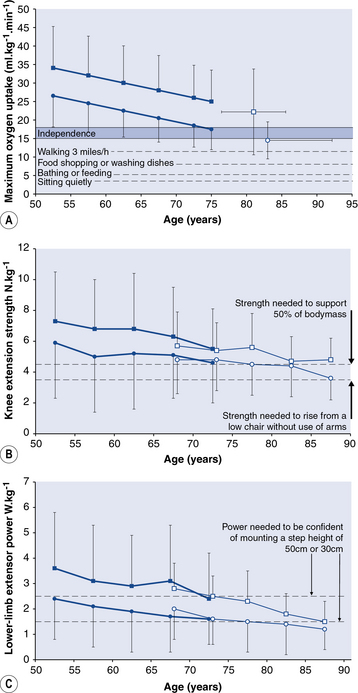

Low physical fitness may be insufficient to meet the energetic demands of certain activities, thus rendering them fatiguing and uncomfortable (Fig. 4.1). For example, muscle strength and power of the lower limbs both predict the ability to perform functional activities such as stair climbing, chair rising and walking speed, but power is the strongest predictor (Cuoco et al. 2004, Puthoff and Nielsen 2007). ‘Thresholds’ exist for physical fitness below which independence is threatened (Fig. 4.2). For example peak values below 15–18 ml · kg-1 · min-1 (Shephard 2009; Fig. 4.1) and muscle strength of the hip flexors strength below 2.3 N · kg-1 (Hasegawa et al. 2008) are both associated with loss of independence. Therefore, as fitness declines (for any reason) the likelihood of activity limitations and loss of independence increases, and individuals are vulnerable to the inevitable effects of further age-related decline.

peak values below 15–18 ml · kg-1 · min-1 (Shephard 2009; Fig. 4.1) and muscle strength of the hip flexors strength below 2.3 N · kg-1 (Hasegawa et al. 2008) are both associated with loss of independence. Therefore, as fitness declines (for any reason) the likelihood of activity limitations and loss of independence increases, and individuals are vulnerable to the inevitable effects of further age-related decline.

Fig 4.2 Physical fitness and function through the lifespan (—) showing the age-related decline seen during adulthood and the implications this may have for loss of independence in later life (Young 1986). The arrows indicate how factors such as gender, health status and physical activity level may influence fitness and function positively (↑) and negatively (↓) and in turn hasten or delay age-related loss of independence.

Physical fitness after stroke

Post-stroke cardiorespiratory fitness

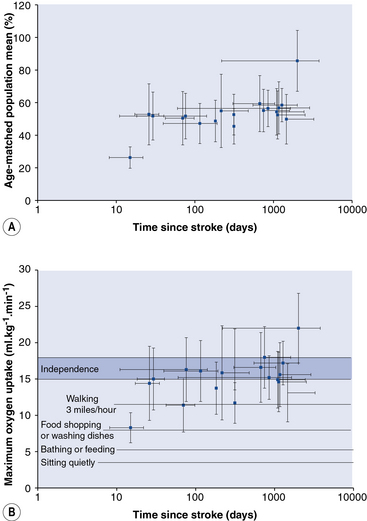

Measures of cardiorespiratory fitness in ambulatory stroke survivors have shown that peak is half (50% to 60%) that expected in healthy people matched for age and gender (Fig. 4.3A). The typical

peak is half (50% to 60%) that expected in healthy people matched for age and gender (Fig. 4.3A). The typical peak observed was ~15 ml · kg-1 · min-1, which corresponds to that implicated in loss of independence in elderly people (15–18 ml · kg-1 · min-1; Shephard 2009). The low values suggest some everyday activities would be difficult to perform since they recruit a high proportion of the

peak observed was ~15 ml · kg-1 · min-1, which corresponds to that implicated in loss of independence in elderly people (15–18 ml · kg-1 · min-1; Shephard 2009). The low values suggest some everyday activities would be difficult to perform since they recruit a high proportion of the peak, resulting in either fatigue or the need to slow down or modify the activity (Fig. 4.3B).

peak, resulting in either fatigue or the need to slow down or modify the activity (Fig. 4.3B).

Fig 4.3 The average peak of stroke patients (19 studies; n=714, not cited) in relation to time since stroke, expressed (A) relative to a healthy, untrained age- and gender-matched population (Shvartz and Reibold 1990), and (B) corrected for body mass in relation to the energetic cost of selected physical activities (Ainsworth et al. 2000) and a proposed boundary in

peak of stroke patients (19 studies; n=714, not cited) in relation to time since stroke, expressed (A) relative to a healthy, untrained age- and gender-matched population (Shvartz and Reibold 1990), and (B) corrected for body mass in relation to the energetic cost of selected physical activities (Ainsworth et al. 2000) and a proposed boundary in (around 15 to 18 ml · kg-1 · min-1) below which a loss of independence is implicated in elderly people (Shephard 2009). Each data point is the mean

(around 15 to 18 ml · kg-1 · min-1) below which a loss of independence is implicated in elderly people (Shephard 2009). Each data point is the mean value reported by each study and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

value reported by each study and the error bars represent the standard deviation.

Abnormal gait and low gait speed are common post-stroke problems caused by factors such as abnormal patterns of movement, use of walking aids, hemiparesis, poor flexibility, contractures, abnormal muscle tone, antagonist coactivation and poor balance. One consequence is an increased energy expenditure which does not contribute to locomotion. Thus the cost per unit distance walked can be several times greater than in healthy people (da Cunha et al. 2002, David et al. 2006, Platts et al. 2006), even after controlling for the confounding effect of a lower gait speed. Peak

cost per unit distance walked can be several times greater than in healthy people (da Cunha et al. 2002, David et al. 2006, Platts et al. 2006), even after controlling for the confounding effect of a lower gait speed. Peak is half that expected in healthy people, yet the

is half that expected in healthy people, yet the cost of walking is typically double. This means that the high cost of even slow walking may involve drawing on a high proportion of the already diminished maximal

cost of walking is typically double. This means that the high cost of even slow walking may involve drawing on a high proportion of the already diminished maximal , leaving little in ‘reserve’. One consequence is that walking is fatiguing and slow and there is little leeway for further deterioration in fitness before walking becomes impossible.

, leaving little in ‘reserve’. One consequence is that walking is fatiguing and slow and there is little leeway for further deterioration in fitness before walking becomes impossible.

Post-stroke muscle strength

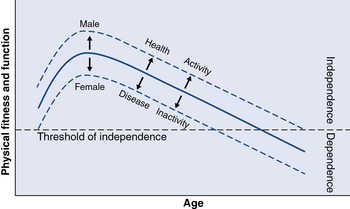

Observational studies comparing the isometric strength of stroke survivors with healthy adults show clear evidence of the muscle weakness, especially on the side of body affected by stroke. This is a defining feature of many types of stroke (Table 4.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree