2.5 Visceral Mobilization

The mobilization of three organs in particular can have an impact on the functionality of the pelvic floor—the bladder, uterus, and rectum. The prostate gland also deserves attention. All of these organs have their own support systems and their own dynamics. When they are in equilibrium with their surroundings, they do not put any strain on each other or on the pelvic floor. Rather, they “stay in place” without outside support. The arterial and venous flow is optimal, and afferent and efferent neural activity is normal, keeping each organ in good health.

In disease or imbalance, the blood flow is altered. Natural defense mechanisms come into play, with an increase in hemodynamic activity. Lymphocytes are drawn to the area to neutralize the aggressor cells. Waste materials have to be carried away by the venous return. This results in local swelling, causing varying degrees of discomfort.

Manipulation of the Bladder

Manipulation of the Bladder

Causes of Imbalance

Arterial. Arterial flow to any organ may be impaired. This can be due to obstruction of the artery, or to an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system that controls the diameter of the blood supplying arteries. The target organ does not receive sufficient nutrients and oxygen. In such a situation, it either does not develop normally, or hydrostatic pressure is insufficient to ensure the necessary tone in the organ and to ensure the correct rhythmic dynamics for proper functioning of the target organs.

Venous. When venous return is impeded, the organ becomes congested. Not only is there insufficient disposal of waste materials, but the size and weight of the organ also change. Eventually, the intrinsic regulatory mechanisms of the organ become insufficient. The organ loses its dynamics and independence. It then depends on support from the surrounding structures and organs. With its weight, it places extra strain on them, which can be compensated for a time, but sooner or later creates a chain reaction. The result is a shift of the organ and maybe even an alteration in its structure and that of the surrounding viscera.

Lymphatic. If the lymphatic system is impaired, the environment of the affected viscera is altered. If the area remains congested for a longer period, the function and dynamics of the organs will also be impaired. Again, swelling will occur, with the consequences described above.

Nervous. Irritation of the autonomic nervous system may result in either stimulation or inhibition. The cause may lie anywhere in the pathway of the affected nerves. The results may be more or less permanent: contraction or dilation of the muscular layer, or hypersecretion or a lack of secretion by the mucous layer (endometrium).

Endocrine. Imbalances in the endocrine system can lead to excessive stimulation of the mucous layer of the uterus. Depending on the viscera concerned, the consequences will have an impact on the pelvic floor muscles. For instance, a proliferation of the mucous layer of the uterus (endometrium) will considerably increase its size and weight. If the situation persists, the intrinsic regulatory mechanisms, as well as the ligamentous support systems, will be impaired. The uterus rests more and more heavily on the bladder. The bladder leans on the vagina, and its anterior wall can be destabilized, resulting in a cystocele, a lowering of the cervix and, possibly, destabilization of the bladder.

General Guidelines for Manipulation of the Pelvic Viscera

General Guidelines for Manipulation of the Pelvic Viscera

The viscera of the pelvis need to be very flexible to adapt to the daily filling and emptying of the bladder and rectum and to the monthly changes in the endometrium, as well as to the enormous changes that take place in pregnancy. Manipulation of the pelvic viscera not only has the goal of repositioning the organ in its proper location, but also, more importantly, to stimulate the arterial and venous blood supply, restore the inner tone of the organ, and return it to its proper, independent functioning.

Initially, it is necessary to discover the nature of the destabilization, and in particular whether the dysfunction is primary or secondary. Depending on the origin of the dysfunction, the focus of treatment is directed to the organ or to the surrounding area.

In primary dysfunctions, the organ loses its intrinsic regulatory capability. It loses its tension and the ability to adapt to its environment. This can have an impact on the tension of its ligaments.

If the disorder starts with a destabilization of the structures surrounding the organ, it can lead to a secondary lesion in the affected organ. This is often caused by scar tissue or adhesions following surgery, or conditions such as endometriosis.

The area immediately surrounding the organ has to be checked first—the bony pelvis (the ilium on both sides, sacrum, and coccyx); the fascia surrounding the organ and the abdominal viscera need to be in equilibrium. If the area surrounding the target organ is not in good condition, it is impossible to restore its balance.

If the symptoms point to congestion, stimulation of the visceral part of the hypogastric plexus, which contains numerous arterial venous and nervous structures, is indicated. Working on this fascia stimulates the structure and has an enormous impact on the autonomic system, inducing changes that last beyond the manipulation.

One must evaluate any abnormal tension in the ligaments to determine whether it is limiting the possibility of physiological movement of the organ. Any tense ligaments could alter the normal position of the viscera and prevent their adaptation to changes in the environment. The organ loses its tension and may destabilize the adjoining organs.

It is only after such conditions have been brought into equilibrium that it is useful to reposition the affected viscera. Once they are in place, stimulating their structure can allow them to recover their proper mobility, motility, and independence. Finally, it is important to check whether the organ is integrated properly with all the pelvic contents specifically, as well as within the craniosacral mechanism and the rest of the body globally.

Manipulation of the Bladder

Manipulation of the Bladder

Access for Manipulations of the Bladder

Access for Manipulations of the Bladder

The bladder can be reached from three different areas:

- By stretching the urachal ligament through the hypogastric area, the resistance of the umbilicovesical fascia can be evaluated (Fig. 2.58).

- Through the obturator membrane, contact can be made with the umbilicovesical fasciae as well as with the lateral surfaces of the bladder.

- The trigone of the bladder and the urethra can be reached through the anterior wall of the vagina.

Description of the Accessible Structures

Description of the Accessible Structures

Abdominal Structures

The bladder, when empty, is a pyramidal organ, hidden behind the symphysis pubis. The top of the pyramid extends into the median umbilical fold (urachus) to the navel. The superior part of this loses its embryological functions, but remains as a ligamentous structure, the urachal ligament. This ligament is situated in the midline, directly under the tendinous linea alba, where the layers of the abdominal muscles join in the midline.

An umbilical artery runs along each lateral border of the upper surface of the bladder. The right and left umbilical arteries meet the urachus at its top. They are embedded in fascial sheaths, the umbilicovesical fascia.

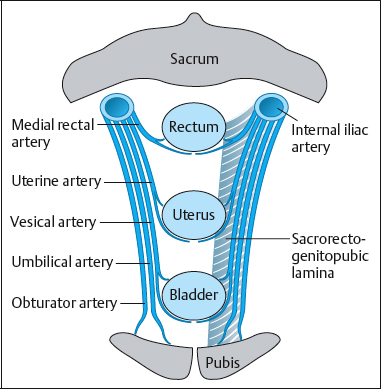

Every large artery originating from the internal iliac artery is accompanied by the mesenchyme in which it developed. This mesenchymal proliferation is projected forward and forms the sacrogenitopubic lamina, which is the visceral part of the hypogastric plexus that extends between the sacrum and pubic bone. The left and right plexus components join precisely in front of or behind these organs, forming supportive retinacula. These stabilizing structures give support to those organs that have to be able to withstand considerable changesinposition andweight. The umbilicovesical fascia is the part of this fascia, which runs forward toward the front of the bladder.

The fibers of the umbilicovesical fascia lose themselves in the parietal pelvic fascia lining the superior surface of the levator ani muscles (Fig. 2.58). These fibers also cover the pelvic surface of the internal obturator and piriformis muscles, both external rotators of the hips. This may explain gait adaptations of internal or external rotation in cystalgia or incontinence. Indeed, internal rotation releases the tone of the muscles concerned and thus the tension in the umbilicovesical fascia. External rotation increases this tension and helps in controlling continence. Hence, if this fascia is drawn upward, the bladder and the levator muscles also move cranially.

The umbilicovesical fascia is also connected to the pubovesical ligaments. These two ligaments are a continuation of the longitudinal muscle fibers of the bladder, and are inserted into the posterior wall of the pubic bone.

Obturator Membrane

The obturator membrane is another way of approaching the bladder and surrounding tissues. This membrane forms a musculotendinous link between the hip joint and the bladder. Regulation of endopelvic pressure is possible through mobilization of the legs. The ligament of the head of the femur (the ligamentum capitis femoris) and the transverse ligament of the acetabulum are fused. The pubofemoral ligament is inserted into this structure. This ligament is attached to the external surface of the obturator membrane and receives the insertion of the external obturator muscle. The internal obturator muscle, also an external rotator, originates from the internal surface of the obturator membrane. Simultaneous contraction of both obturator muscles pulls on the membrane from two directions and enhances the functioning of the structures running through the obturator canal. It also modulates intrapelvic pressure [Croibier 1993].

By greatly enhancing the tone of the obturator muscles, it is also possible to use tension in the obturator membrane as a compensatory mechanism to create intrapelvic support for a destabilized bladder.

Internal Examination

The posterior wall of the bladder can be accessed by internal manipulation.

Female patients: vaginal exploration. During vaginal exploration, it is possible to feel the urethra through the anterior wall. Moving higher, the bony pubic symphysis can be palpated. The trigone of the bladder can be felt here. This is the small triangle in the posterior wall of the bladder between the two incoming ureters and the outlet to the urethra. If the tissue feels dense and thickened, the triangle is fibrosed, often as a result of recurrent cystitis.

This small triangle has a different embryological origin from that of the rest of the bladder. It is of mesonephric origin, and develops in close relationship with the (paramesonephric) gonads [Williams and Warwick 1980]. It contains cells that are sensitive to hormonal changes. Hormonal imbalance can be a source of frequent cystitis. As it forms part of the septum between the bladder and the vagina, this tissue can influence both structures.

If the exploration is directed to the anterior vaginal wall, one can feel whether this wall has a normal tone. A cystocele can sometimes be found, with destabilization of these structures. The suspension system of the uterus should keep the anterior vaginal wall in place, aided by the uterosacral ligaments that run between the cervix (with some high vaginal fibers) and the sacrum (segments S2–S4). There is also a transverse suspension system in the uterus— the broad ligament and Mackenrodt’s ligament, which are embedded in the parametrium and attach the upper vaginal wall to the lateral pelvic wall, where they meet the pelvic fascia. Its fibers accompany the uterine and vaginal arteries.

Destabilization of the suspensory system of the uterus or loss of its inherent tension are common causes of cystocele. When the uterus loses its inherent tension, it may lean more heavily on the bladder (anteversion), or may start to descend into the vaginal cavity (prolapse). In the case of first-degree or second-degree anteversion of the uterus, there is mostly excessive tension of one or both of the uterosacral ligaments. In the case of a first-degree uterine prolapse, the position of the uterus is somewhat vertical, and at the same time there is a lack of muscle tone in the pelvic floor muscles. The muscular strength of the bulbospongiosus, the transversus perinei, and the levator ani should be evaluated.

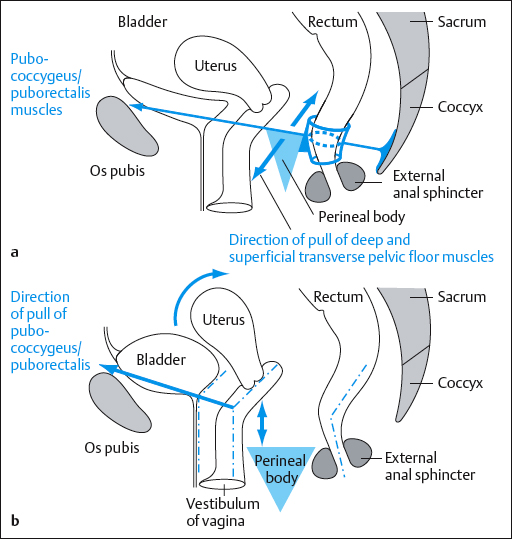

In a normal situation, the deep and superficial transverse pelvic floor muscles aid in fixing the perineal body. Helped by contraction of the pub-ococcygeus, the posterior vaginal wall is drawn forward. A virtual angle formed in the vagina supports the cervix when needed (for instance, when the bladder is full) (Fig. 2.59).

If the transverse pelvic floor muscles are too weak, they do not exert back-to-front pressure on the vagina and bladder. The virtual angle straightens out, and the natural barrier to the descent of the uterus disappears.

Male patient: rectal exploration. In the male, the posterior wall of the bladder can similarly be felt by rectal exploration (provided the gluteal muscles are not too well developed). In the prone position, the trigone of the bladder can be palpated just anterior to and above the prostate. This procedure makes it possible to evaluate the quality of the rectovesical septum of Denonvilliers. Of course, the prostate gland is also evaluated: How big is it? Can the two lobes be distinguished, and are they symmetrical? Are there nodules? Is there congestion of one or both lobes? The muscle strength of the levator ani muscles should also be evaluated.

Testing and Manipulating the Bladder

Testing and Manipulating the Bladder

Stretching the Urachal Ligament and Lifting the Bladder

The patient sits on the treatment table, with the feet on the floor. The therapist stands behind the patient and applies the fingertips of both hands just above the pubic bone. Inducing a slight flexion of the thorax helps release tension in the abdominal wall. Reaching deep inside, slightly behind the pubic bone, the therapist then very gradually starts pulling the tissue upward, “listening” to the tension of the structure. The therapist can evaluate whether there is more tension on the right or the left, which may indicate an imbalance of the fascia or the bladder on that particular side (Fig. 2.60). The treatment is a continuation of the examination: the therapist firmly but gently pulls the tissue upward as far as possible. The therapist can also ask the patient to lean toward one side to apply more tension to the contralateral part of the fascia. The procedure is completed by pushing the patient’s thoracic spine forward, to stretch it. The whole sequence is repeated several times.

Procedure in the supine position. The patient lies with flexed legs to release tension in the abdominal wall and with a pillow under the head. The therapist stands next to the patient’s knees, facing them. Placing both thumbs on the area above the pubic bone, the therapist pushes down behind it as far as possible, to make contact with the bladder. For testing, the therapist first gently pulls on the prevesical fascia with both thumbs, to evaluate whether one side is more tense than the other. For treatment, the therapist pulls as much as possible on the tissue, firmly but gently (Fig. 2.61). Pulling slightly sideways, the impact is greater on the prevesical fascia on the contralateral side [Barral and Mercier 1987].

Testing and Treating the Urachus and Medial Umbilical Ligaments

The patient lies in the supine position, prepared for a vaginal examination. The therapist stands on the right side of the patient, with one knee on the treatment table. The patient puts the right foot on the therapist’s thigh. The therapist enters the vagina with two fingers, with the hand in pronation. The therapist gives a slight prestretch into the levator ani muscles and then asks for a voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. The patient should be able to hold this contraction for several seconds. The therapist evaluates the muscular strength and any left–right imbalance. If muscular strength is sufficient, the therapist does not need to proceed any further. If there is a problem, however, the therapist puts his/her thumb on the middle of the urachus. With firm pressure in order to remain in contact with the fascia, he or she pulls the urachus (as well as prevesical fascia and bladder) upward. When the contraction is repeated by the patient, the response will be much better (Fig. 2.62).

If one side is limited, the medial umbilical artery on that side can be lifted during a voluntary contraction. This enhances the muscle contraction. Sometimes a better contraction can be obtained by working on the medial umbilical artery from the opposite side. This exercise can be repeated a few times. It may be important to search for the exact spot on the ligaments at which the technique is most effective. After several stimulations, the patient is usually able to perform much better and contracts the pelvic floor muscles satisfactorily without help. The result of this procedure is immediate, but it should be repeated periodically over several sessions [Barral 1993, pp. 99–101].

This technique can also be applied effectively in male patients, using rectal palpation. The palpating index finger is moved slightly to the left or right to evaluate the muscle strength of the levator ani. The technique can also be used to restore muscle strength in the pelvic floor muscles.

Obturator Membrane

The patient is in the supine position. The therapist stands on the right side of the treatment table, with the right knee on the treatment table. The patient places the right leg over the therapist’s knee, in slight abduction. The therapist brings his or her right thumb behind the adductor muscles, as far up as possible. The obturator membrane can be found automatically using this maneuver. If the thumb slides a little more medially, the finding can be confirmed by feeling the bony ramus of the pubic bone (Fig. 2.63). The therapist evaluates the tension in the membrane. The therapist places the radial surface of the left thumb lateral to the contents of the abdomen, just behind the right pubic ramus. Now the therapist tries to shift the bladder with the thumb to the left. If there is normal tension of the membrane and the bladder yields, the right thumb will penetrate deeper into the membrane. The bladder should yield and then come back easily. If not, it means that the bladder is adherent. If it remains in its induced position, tension must be impacting on the bladder from the opposite side.

The following technique is applied to restore normal tension to the obturator membrane: the patient is still supine, and the therapist is on his or her right side. The therapist brings the right arm from medial to lateral under the patient’s bent knee (Fig. 2.64). The desired degree of flexion, internal rotation, and slight adduction can be induced in this way. External rotation of the hip is then requested, while resisting the movement for 5s. This procedure is repeated two or three times. This is not a hold–release technique. The therapist keeps the leg in the same position throughout the exercise. The contraction is repeated three or four times before retesting the membrane [Barral 1993, pp. 26–7].

Manipulation of the Prostate

Manipulation of the Prostate

Examining the Prostate

Examining the Prostate

Examining the Median Umbilical Fold (Urachus)

The patient lies supine, with the knees bent. The therapist stands behind the patient’s head. The therapist places his or her fingertips on the skin just above the pubic bone, while both thumbs keep the small intestines away from the bladder. The therapist draws the fingertips toward the thumbs and evaluates whether there is any tension resisting this movement. This tension can be unilateral, and may be caused by adhesions on the anterior surface of the prostate [Barral 1993, p. 261] (Fig. 2.65).

Examining the Pelvic Floor Muscles

Examining the Pelvic Floor Muscles

The patient bends over the treatment table and rests their head on their arms. The therapist stands behind the patient. With the thumbs, the therapist evaluates the tension in the ischioanal fossa. This is the area between the lateral angle of the coccyx and the ischial tuberosity. Pushing the thumbs inward in order to put tension on the perineum, the therapist then asks the patient to inhale deeply, to enhance contact with the perineum. During expiration, the therapist evaluates the quality of the withdrawal (Barral 1993, p. 263] (Fig. 2.66).

Examining the Prostate

Examining the Prostate

The patient lies prone. The bladder, and if possible the rectum, should be emptied before the treatment. The therapist finds the prostate by rectal palpation before reaching the bony structure of the pubic symphysis. With better developed gluteal muscles, it becomes more difficult to reach the prostate.

A therapist trained in osteopathic treatment and/or visceral mobilization can check whether the gland has two distinct lobes and whether the lobes are of normal consistency. A congested lobe can be caused by excessive tension in the visceral part of the hypogastric plexus. If there is tension in this visceral pelvic fascia, several consecutive stretches by the index finger—slow and prolonged (reaching the end range, but not aggressively)—on the affected side will have an enormous impact, not only with regard to tension in this fascia but also by stimulating perfusion. Stretching the arteries improves the blood flow velocity and may also result in an autonomic response that will take hours to subside.

As often in osteopathic treatment, the examination and treatment are very closely linked.

Manipulating the Prostate

Manipulating the Prostate

Stretching the Umbilicovesical Fascia and the Rectovesical Septum

The patient is in prone position. The therapist stands on the left side of the treatment table. With the right index finger, the therapist performs rectal palpation. The supinated left fist is placed under the patient’s lower abdomen, in the hypogastric region. The rectal finger finds the tissue between the prostate and the anus. As this tissue is grasped between the index finger and the thumb from the outside, the transverse pelvic floor muscles are held between these two digits. The therapist applies gentle traction, simultaneously bending his or her left hand toward the wrist. The knuckles of this hand are in contact with the prevesical fascia, stretching it. The whole musculofascial system is stretched between the two fixed points, releasing the tension they might exert on the prostate [Barral 1993, p. 277] (Fig. 2.67).

Working on the Visceral Part of the Hypogastric Plexus

External technique. This procedure can be carried out just before or after the above technique, since the patient must be prone and with the therapist’s left supinated fist under the patient’s abdomen.

With the ulnar side of the right arm, the therapist applies dorsoventral pressure (in the direction of the treatment table) on the lateral side of the sacrum (Fig. 2.68a). The pressure should be firm, while the left wrist in the hypogastric region tries to elevate the bladder (Fig. 2.68b). This reduces tension in the puborectalis muscle, which is closely linked to the sacrorectogenitopubic lamina. The therapist builds up pressure and releases it again consecutively a few times. After the last time, the therapist can choose to release the contact very suddenly, thus providing additional stimulation [Barral 1993, pp. 272–3].

Internal technique. The patient is in the prone position. The therapist carries out a rectal exploration. By applying pressure laterally, he or she ensures that the sacrorectogenitopubic lamina on that side is stretched. By working slowly, repeatedly building pressure and letting go, the therapist releases tension in this fascia (which contains some muscle fibers).

Direct technique for the prostate. After all the structures around the prostate are sufficiently balanced, the therapist can apply a procedure directly to the prostate. With the index finger in the rectum, the therapist palpates the lobe that appears to be more swollen, vibrating it [Weischenck 1982, p. 215]. If tension previously existed in the fascia and if the reason for the swelling was congestion, the volume will change immediately. The procedure is next applied to the other lobe.

Manipulation of the Uterus

Manipulation of the Uterus

The uterus is an organ that takes on a variety of shapes and positions. A different shape or position may not cause a problem, so long as the uterus adapts to its surroundings. After all, the uterus changes during the monthly cycle and during pregnancy, usually without causing any difficulties.

Fixations occur mostly due to abnormal tension of the uterine ligaments. They are responsible for a large number of complaints. Most of them result in congestion of the pelvic area, and eventually in pelvic floor problems.

Positions of the Uterus

Positions of the Uterus

The normal position of the uterus is in the center of the pelvis, with the body of the uterus tilted forward. The body of the uterus is situated on a line drawn from the umbilicus to the tip of the coccyx. The uterus lies above a line drawn between the upper rim of the pubic bone and the sacrococcygeal joint. If the uterus is in its normal position, the cervix extends into the upper part of the anterior wall of the vagina, at an angle of about 90 h. At the isthmus, the cervix makes a slight angle with the body of the uterus. This angle, facing down, is between 120 h and 140 h . The uterus may be malpositioned in a number of ways, as discussed below.

Anteposition, Retroposition, Lateroposition, Prolapse

In these positions, the uterus is tilted correctly, the angulation at the isthmus is normal, but the uterus in its totality is pulled forward, backward, or to the side of the pelvis. Prolapse is present when the uterus is situated too low in the pelvis—a very common malposition. Elevation of the uterus is less common. When present, it is usually the result of a tumor.

Anteversion, Retroversion, Lateroversion

In these conditions, the uterus lies in the center of the pelvic cavity. However, the uterus as a whole has tilted forward, backward, or sideways. The angulation at the isthmus is within normal range.

Torsion

This is the result of simultaneous pulling of one uterosacral ligament on the cervix and of the round ligament on the same side or the broad ligament on the opposite side on the fundus. This combination results in twisting of the body of the uterus on the cervix. Once the strain caused by these ligaments is released, the torsion disappears. It does not cause structural change in the uterus.

Structural Changes in the Uterus Itself

Structural Changes in the Uterus Itself

Anteflexion, Retroflexion, Lateroflexion

The uterus is situated in the center of the pelvis, but the angle between cervix and body of the uterus is either too small (anteflexion), or too large (retroflexion), or the uterus is deviating sideways (lateroflexion). The cervix or body may or may not be in its normal position. Barral [1993] states that osteopathic treatment would have little effect in these conditions. However, other authors [Richard 1992, Woodall 1983] describe normalization techniques for deviations of flexion. These techniques are described here, although one must be aware that it may not be possible to make radical changes in an organ that has evolved abnormally because of a situation that has often been present from the time the organ was developing. The author believes that this situation should be corrected if possible, and that all the ligaments should be in a normotensive state, even if the organ is malformed. If its ligaments are in a normotensive state, the organ may adapt to its surroundings and the malformation will not generate a series of consequences for the pelvic floor muscles, unless the volume of the uterus is greatly changed.

Myoma, Fibroma

These benign growths can lead to misdiagnosis. Anteflexion of the uterus may be considered when in fact there may be a myoma on the anterior side of the fundus. It is also true that a myoma can cause flexion in the uterus.

Osteopathic treatment will not make the fibroma subside, but will improve overall mobility and the blood supply and tone in the uterus and surrounding tissues. The area will be better balanced, and this provides the best possible chances for symptom reduction.

Stabilizing and Orienting the Structures of the Uterus

Stabilizing and Orienting the Structures of the Uterus

Different ligaments have a stabilizing or orienting effect on the uterus.

Uterosacral Ligament

This ligament stretches from the posterior aspect of the cervix, next to the lateral angle of the isthmus, to the anterior surface of the sacrum, medial to the sacral foramina [Perlemuter and Waligora 1975]. It contains smooth-muscle fibers and can therefore contract. It is interesting to note that this ligament also contains fibers of the hypogastric plexus, since its fibers are mingled with the superior borders of the visceral part of the hypogastric plexus (sacrorectogenitopubic lamina) The uterosacral ligament is responsible for most of the lesions in which the cervix is pulled toward the sacrum, including anteflexion and torsion.

Round Ligament

This ligament starts at the lateral superior angle of the uterus. It travels forward, dives into the inguinal canal, appears again on the anterior surface of the pubic bone, and travels down toward the labia major, where it is attached. Near the uterus, it contains much nonstriated muscle, but the terminal part is purely fibrous. This long ligament serves merely for orientation. It is usually not a leading factor in destabilizing the uterus, but once the uterus is destabilized, the round ligament may maintain the destabilized position.

Broad Ligament

This ligament has a different structure from that of the ligaments described above. It consists of a peritoneal fold over the uterine tube, and passes from the side of the uterus to the lateral wall of the pelvis, where it continues into the pelvic fascia. Unlike the ligaments described above, this one contains neither muscle fibers nor fibers that are part of a neurovascular plexus. Strain on this ligament is caused by disorders of either the tube or the ovary, as this ligament also contains the ovarian ligament, or (most often) by traction arising from the peritoneum or the pelvic fascia. The latter can be caused by adhesions or scar tissue, following trauma, surgery, or inflammatory processes. Tension in these ligaments causes malpositioning of the uterus in a lateral plane.

The transverse cervical ligament of Mackenrodt is situated in the parametrium and attaches to the side of the cervix and the lateral fornix of the vagina. This ligament contains the vessels supplying the uterus and vagina.

Puborectalis Muscle

This muscle is responsible for anterior traction on the cervix, by which it may cause retroversion or anteposition. The visceral part of the hypogastric plexus is also in continuity with this muscle. Contraction of this muscle stimulates all of the pelvic content.

Muscle training of the puborectalis not only helps support the pelvic viscera correctly, but also helps drain the pelvis and its organs. This creates a better balance, which may explain why the bowel often also functions better—a secondary gain resulting from treatment of the pelvic floor muscles.

Diagnostic Tests for Lesions of the Uterus

Diagnostic Tests for Lesions of the Uterus

Observing the Patient in the Standing Position

Observation of the patient’s posture can provide some indication of the existence of compensatory patterns. The observation can point toward a degree of imbalance that may or may not be confirmed by the examination outlined below.

The patient may have either normal or exaggerated lumbar lordosis, or perhaps even lumbar kyphosis or a flat back [Busquet 1992, pp. 158– 64].

Exaggerated lumbar lordosis. This posture may be a defense mechanism to avoid too much pressure on the pelvic viscera. This can be of abdominal or of pelvic origin. With a normal posture, the contractions of the pulmonary diaphragm whilst breathing affect the hypogastric region. The pyramidalis muscle provides additional strength to this area. In a posture with normal lordosis, the pubic bone receives the weight of the abdominal contents and there is no load on the pelvic organs. If the abdominal volume is large, or in abdominal pain or discomfort, or in pelvic disorders, tilting the pelvis forward can provide relief, because it reduces the abdominal and pelvic compression. This results in lumbar lordosis, perhaps accompanied by an opening of the superior parts of the ilia in the frontal plane. With flare-out, there is drawing in of the ischial tuberosities and a decrease in the normal tension of the transverse fibers of the pelvic floor muscles. In such cases, the sphincter has to do more work.

Exaggerated kyphosis. Reduced abdominal volume (abdominal ptosis) or pain relieved by compression may be compensated for by lumbar kyphosis. Also, in cases of pelvic pain, the pelvic cavity may be compressed by anterior flexion of the coccyx, retroversion of the sacrum, and tension on the transverse fibers of the pelvic floor muscles, bringing the ischial tuberosities closer together. In this case, the weight of the viscera will no longer be carried by the pubic bone, but will act on the uterine fundus and/or the bladder. More work will be required of the sphincter muscles, and in the long run their effectiveness is impaired.

Locating the Uterine Fundus in Supine Position

First step. The patient lies supine, with the legs straight. The therapist stands on the right side of the treatment table, facing the patient, and places the base of his or her hand on the abdomen, a few centimeters above the pubic bone. The uterine fundus normally lies under the peritoneal sac. This is where the hand makes contact with the abdomen—just under the curvature. Light compression toward the back normally encounters the uterine fundus.

If the fundus is not there, the hand sinks further down, without meeting significant resistance. This is the case if the uterus is retroverted. If there is no resistance to indicate the position of the fundus, it may be situated just above the pubic bone (first-degree anteversion) or more laterally (lateroversion, lateroflexion, or lateroposition). Attention is needed to avoid mistaking a distended bowel for a laterally placed fundus.

Second step. The patient bends her legs. The therapist presses deeply into the abdomen at the point described above, using the front of the fingertips. The other hand can help to push aside the small intestines. The fundus can be recognized as a somewhat rounded and firm mass. It may be located behind the pubic symphysis.

Locating the Cervix by Internal Palpation

The therapist stands on the patient’s right side, with the right knee on the treatment table. The patient lies supine, with the right leg bent and placed over the therapist’s knee.

The cervix is normally found on the anterior wall of the vagina, where it is felt as a cylindrical protrusion. If the cervix cannot be reached because it is positioned higher in the vagina, the finger presses the anterior wall of the vagina downward in the direction of the pubic bone. This draws the cervix closer. If this maneuver does not locate the cervix, evaluation of the density of the tissue in front of the finger is indicated. The uterus may lie between the pubic symphysis and the finger. If the uterus is not in this location, the cervix or uterus may be found in the posterior or lateral walls of the vagina.

It is important to locate the ostium in order to confirm that the cervix has actually been found. The direction of the cervical canal needs to be assessed. This provides information about the exact position of the cervix and the probable position of the uterus, which can then be confirmed by external palpation.

Evaluating the Tension in the Ligaments by External Palpation

Round ligament. If there is tension in the round ligament, it can be felt like a cable running almost vertically across the ramus pubis, between the pubic tubercle and the midline. This ligament is too tense when the fundus is inclined too far laterally, or is drawn backward.

This can be checked with the patient in the supine position, starting the palpation with the fingertips from just lateral to the pubic tubercle, to the midline and back. If there is a “cable,” this maneuver stretches it and it then “jumps back” into place. In the course of the examination, the tension in the ligament subsides. Thus, the first movements are the most significant.

Broad ligament. The patient lies on her left side, with both knees bent. The therapist stands behind the patient, facing her back. With the fingers of both hands, the therapist finds the way lateral and posterior to the colon, and reaches as far down into the left pelvic cavity as possible. Pulling the fingers back, the therapist tries to lift the uterus toward the right side of the pelvis. This evaluates the tension in the left broad ligament. The patient now turns to the other side, and the sequence is repeated. The tension on the two sides is compared.

Evaluating the Tension in the Ligaments by Internal Palpation

Broad ligament. Excessive tension of the broad ligament will cause complete lateral deviation or lateroversion of the uterus. Vaginal exploration will reveal a malposition of the cervix: it will be placed more laterally in the vagina, and/or one of the lateral fornices will be closed while the other will be wide open. Trying to move the cervix in a frontal plane, the side of a tense broad ligament does not stretch easily.

Uterosacral ligament. Moving the cervix forward detects any tension in the uterosacral ligaments. Under normal conditions, the cervix can be moved, but springs back into place with a degree of elasticity. If one of these ligaments is excessively tense the cervix cannot be mobilized, or it will be pulled back too quickly after its mobilization. Where there is tension of only one uterosacral ligament the position of the uterus will be found to be asymmetrical.

Puborectalis muscle. When this muscle is too tight, the cervix is drawn forward. Either mobilization of the cervix backward in the sagittal plane will be difficult, or the cervix returns to its initial (anterior) position too quickly.

Normalization of the Uterus

Normalization of the Uterus

In most cases, osteopathic treatment of the uterus deals with excessive tension in its ligaments. When a problem is detected during a diagnostic examination, it is treated immediately. The affected ligament is stretched by pulling in the direction of the resistance to lengthen it, or by applying pressure or pulling in a plane at right angles to the tense ligament. If this does not help, one can try to relax it by approximating the origin and insertion. In most cases, corrections are done with the patient supine, since the examination is also carried out in this position.

Anteversion

Usually, there is excessive tension in both uterosacral ligaments. Anteversion of the uterus will also be found more often when the weight of the abdominal viscera is supported by the uterus instead of the pubic bone. The condition of the viscera therefore has to be checked first.

To correct an anteversion, the therapist can use one or two fingers. The goal is to relax the posterior ligaments so that the cervix can be moved forward and the fundus upward. If the therapist uses one finger, the index finger is placed behind the cervix (Fig. 2.69). If the index and middle finger are used, the middle finger presses backward against the posterior wall of the vagina, while the index finger, resting against the posterior side of the cervix, moves the cervix forward (Fig. 2.70). At the same time, the therapist tries to insert the fingers of the left hand on the abdomen between the pubic bone and the fundus, trying to reach the fundus and lift it up.

The cervix is often found high in the vagina, so that the fingers cannot reach behind it. When pressure is applied to the anterior fornix, it may be possible to draw the cervix closer toward the pubic bone (Fig. 2.71).

If the patient turns onto her right side, facing the therapist, the therapist can reach more deeply into the vagina. In this position, the patient’s left leg can easily be mobilized and the hip completely flexed, making deeper penetration possible [Barral 1993, pp. 160–1].

The tension in the uterosacral ligaments can sometimes not be relaxed, and the cervix will not come closer. When lateral pressure is applied high inside the vagina, the visceral part of the hypogastric plexus is stretched. An autonomic reaction is elicited, often resulting in relaxation of the uterosacral ligament.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree