Use of a Varus-Valgus Constrained but Nonhinged Prosthesis for Ligament Insufficiency in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty

Paul F. Lachiewicz

INDICATIONS

The prevention and management of instability after primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are important issues. Instability is a common mechanism of failure and need for revision after primary TKA. In one series of 440 revisions, 63% failed within 5 years, and instability was the reason for failure in 27% (1). In another study of 212 revisions, instability was the mechanism of failure in 21% of cases (2). Instability was the second most common mode of early failure and the third most common mode of late failure (2). Instability may be categorized as flexion instability, varus-valgus instability in extension, and global instability. Flexion instability may be a result of attenuation, rupture, or overrelease of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) with PCL-retaining prosthetic components (3). It may also occur with posterior cruciate substituting, rotating, bearing, and so-called deep-dish prostheses caused by improper gap balancing in flexion, undersizing of the femoral component, excessive posterolateral corner and lateral soft tissue releases, or poor design of the tibial spine (4).

FIGURE 15-1 Preoperative photograph of the legs of an 86-year-old woman with instability of the left knee. |

FIGURE 15-2 Preoperative radiograph measures 34 degrees of anatomical valgus alignment. There is medial gapping, suggesting incompetence of the medial collateral ligament. |

There are numerous indications for the use of varus-valgus constrained (nonhinged) components in primary TKA. The most common indication is the arthritic knee, usually in an elderly, osteopenic female patient, with severe valgus deformity and attenuation or functional absence of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) (Fig. 15-1) (5). These knees usually have a valgus deformity of 20 degrees or greater (Fig. 15-2). In all patients with a preoperative valgus deformity, the author’s primary goal is a balanced, stable knee in 4 to 6 degrees valgus alignment. In knees with fixed deformities, ligament balancing, with release of contracted structures on the concave side of the deformity, is performed (6). The author routinely uses a posterior cruciate substituting prosthesis for primary TKA. Spacer bars are used to check varus-valgus stability after bone resection and appropriate ligament release. The author implants the varus-valgus constrained components only if the MCL cannot be tensioned properly. The author has no experience with MCL advancement or grafting in primary TKA (7,8). The presence of a screw or staple at the origin or insertion of the MCL on preoperative radiographs should raise the surgeon’s suspicion that this ligament may be incompetent once the bone resections are performed. Iatrogenic damage transection of the MCL or lateral collateral ligament can infrequently occur during primary TKA. The collateral ligaments may be especially vulnerable during proximal tibial or posterior femoral condylar resections. It has been reported that primary repair of the MCL can be successful in knees with retention of the PCL (9). The author, however, uses a varus-valgus constrained component in this clinical situation as, in his opinion, suture repair of the collateral ligament is unreliable and avoids the need for postoperative bracing. The other disorders and diagnoses for which a varus-valgus constrained component may be necessary are listed in Table 15-1 (Figs. 15-3 and 15-4).

In these clinical situations, the author initially attempts to perform a posterior cruciate-substituting prosthesis if at all possible. If one or both collateral ligaments appear incompetent, however, the author proceeds with the varus-valgus constrained components rather than prolonged postoperative immobilization or bracing.

TABLE 15-1. Possible Indications for Varus-Valgus Constrained Components | |

|---|---|

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Varus-valgus constrained components should not be implanted if the MCL and lateral collateral ligaments are intact and the knee is able to be balanced in both flexion and extension. With certain implant systems, however, a posterior stabilized (rather than constrained) tibial polyethylene liner may be used if the constrained condylar components are deemed necessary because of bone deficiencies of the distal femur or proximal tibia. The major contraindication to the use of these components is complete absence of either collateral ligament or deficiency of the medial epicondyle or medial femoral condyle, such that even a constrained condylar component will not provide stability. In such cases, a hinged-linked prosthesis may be required (10,11). However, this situation should be very unusual in primary TKA.

TECHNIQUE

Patients with ligament insufficiency and a knee deformity that will require a varus-valgus constrained TKA are generally not candidates for a “mini-incision” approach. A thigh tourniquet set at 100 mm Hg above systolic blood pressure is routinely used. The author uses a 15- to 18-cm midline skin incision and a medial parapatellar capsular approach.

FIGURE 15-5 After exposure of the knee, the medullary canal of the distal femur is entered using an anterior referencing jig. |

FIGURE 15-6 Line representing Whiteside’s lines indicating the anteroposterior axis. The epicondylar axis of the distal femur is marked, and the initial anterior femoral resection is performed. |

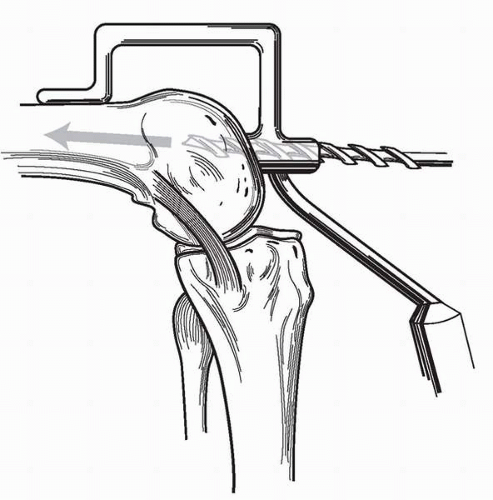

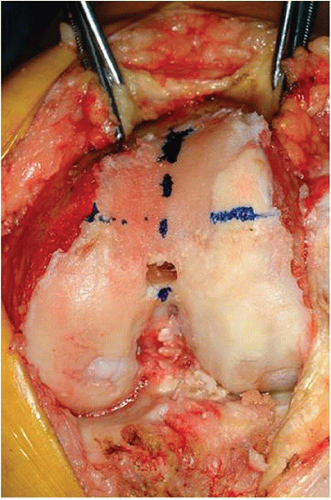

After exposure of the knee and removal of periarticular osteophytes, the surgeon drills the medullary canal of the distal femur using an anterior referencing jig (Fig. 15-5). Using the so-called Whiteside’s line, the correct rotational alignment for the femoral component (epicondylar axis) is marked with methylene blue (Fig. 15-6) (12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree