Chapter 24 Unique Considerations for Foot and Ankle Injuries in the Female Athlete

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction

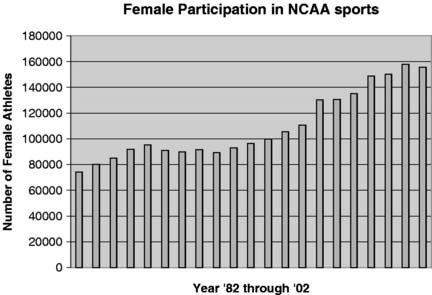

The passage of Title IX* is arguably the most important event in the timeline of women’s participation in U.S. athletic endeavors. By almost any measure, the numbers of female athletes have exploded in multiple sports in the decades since 1972. Before Title IX, approximately 1 in 27 girls participated in sports; that number is now nearly 1 in 3.1 The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) tracks women’s sports participation in its member institutions; the data are self-reported and are useful for evaluating general trends. In 1981, total athletes numbered 74,239. By 1993, the total had risen to 105,532 and then in 2001 to 155,513 (Fig. 24-1). In general, the increase in participation reflects the addition of women’s teams to institutions. The increase also reflects the elevation of previously emerging sports such as ice hockey and water polo to normal status and championship competition. Additional emerging sports, such as synchronized swimming, archery, badminton, equestrian events, squash, and team handball also have increased the numbers of athletes reported.

The increase in the number of women participating in sports and the increase in their level of competition has provided a new opportunity to study the effects of different sports on the athlete. Some sports provide the opportunity to directly compare injury rates for both genders. Other sports are the exclusive domain of the female athlete. There is great interest in identifying preventable injuries, whether they are sport specific or gender specific. The sports identified as causing the highest number of injuries in the female athlete are basketball, volleyball, field hockey, and gymnastics. Sports engendering the fewest injuries are golf, swimming, squash, and archery.2–7 Additional information also has been garnered by the study of female military recruits and their physical performance compared with male peers. Military studies are intriguing because the male and female populations are subjected to the same conditions of training and physical standards.

Their data reveal significant and more rapid improvement in performance over sequential years for women compared with men. The higher injury rates initially reported in women have gradually begun to decline as women have adapted to the rigorous schedule.8 Physiologic differences, particularly in upper body strength in women, may be permanently limiting, although women appear to have comparable or better aerobic capacity.9 Other preliminary studies seemed to indicate a significantly higher rate of injury in the female athlete; however, follow-up studies demonstrated the injury rate to be sport specific. In these studies, proper conditioning resulted in injury rates equivalent to male athletes.

Anthropometric studies provide interesting data concerning anatomic differences between women and men.10 In women, lower extremities constitute 51% of their total height, compared with 56% in men. This difference improves the mechanical advantage for men in activities requiring striking, hitting, or kicking because of the greater force than can be generated by their legs as longer levers. The female has a wider pelvis, greater varus of the hips, and greater genu valgus than the male. As a result, females have a lower center of gravity, and in sports requiring excellent balance, such as gymnastics, females have a distinct advantage. As a result, the balance beam is a required element in competition for female gymnasts and is not included in the competition for male gymnasts. Female gymnasts typically also have better joint mobility, improving their flexibility—another trait valued in gymnastics. The alignment differences at the hip and knee may be one factor, along with the level of conditioning, contributing to higher percentages of overuse syndromes in the lower extremity in female athletes.

Sport-specific disorders

Ballet (Also See Chapter 21)

The female classical ballet dancer is unique in her requirements for the lower extremities.11,12 The dancer uses either a thin-soled slipper or toe shoe. The dancer typically will participate in several classes, rehearsal for performances, and then the performance or performances. The lower extremities are called on to absorb all the force of landings on the wooden dance floor. The consequence of the schedule of training and performance and the type of shoe for the foot leads to chronic injuries such as tendinitis, tendinosis, and impingement syndromes. The most common acute injury is the inversion sprain, usually occurring on landing a jump. Fatigue, improper technique, and anatomic variation from optimal body type all can be factors in acute and chronic injuries. The lower leg, foot, and ankle make up approximately 40% of dance injuries in a sport in which the lifetime incidence of injury is 90%.13

Posterior Ankle Pain (Also See Chapter 2)

Ballet requires extreme plantarflexion of the foot for en pointe work. In this extreme position, soft tissues posterior to the ankle can be compressed and irritated. Any one of the following structures posterior to the ankle can cause symptoms: an os trigonum, a large posterior process of the talus, or a large dorsal process of the calcaneus. Symptomatic flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendinitis can be caused by these impingement scenarios. Diagnosis of this suspected condition can be supported by local tenderness proximal to the sustentaculum tali and pain with resisted plantarflexion of the great toe. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically will demonstrate fluid within the sheath of the tendon and sometimes marked tenosynovitis.14 Preservation of the function of the FHL tendon is paramount in dancers. Treatment should be aimed toward minimizing the inflammatory condition, with surgical intervention timed to allow appropriate recovery. In some instances, simple release of the FHL is adequate; in other cases, excision of the os trigonum or posterior process of the talus may be required. FHL tendon symptoms are most commonly associated with ballet; however, participants in other sports such as soccer increasingly are demonstrating the same entity.

Acute Injuries

Nearly half of reported dance injuries are categorized as acute. The most common injuries occur as the dancer lands with a loss of balance. If the dancer lands in en pointe position, the ankle is more stable, causing a midfoot injury rather than the typical anterior talofibular ligament injury. Radiographs should be obtained in the dancer who cannot walk more than three steps (limping is acceptable) and in whom there is tenderness over important anatomic landmarks. Foot x-rays should be obtained if there is tenderness over the navicular bone or the base of the fifth metatarsal. If there is tenderness over either the fibula or the medial malleolus from the tip to 6 cm proximal to the tip, ankle films should be obtained.15,16

The most commonly overlooked fractures include the talar dome (see Chapter 14), the lateral process of the talus (see Chapter 14), the os trigonum (see Chapter 14), the anterior process of the calcaneus, and the proximal fifth metatarsal. Younger dancers can be more difficult to evaluate, often requiring repetitive x-rays. A high index of suspicion should be maintained, especially in the face of soft-tissue swelling over the physes of ankle or foot bones.

As in other athletes, inversion injuries can cause damage to structures other than the anterior talofibular ligament. Syndesmosis tears, osteochondral lesions of the talus, and subluxation or longitudinal tears of the peroneal tendons all may occur. Dancers also are at risk for subluxation of the cuboid, either associated with an inversion injury to the ankle or from repetitive plantarflexion and dorsiflexion. In this clinical entity, the base of the fourth metatarsal becomes dorsally displaced and the fourth metatarsal head displaces in a plantar direction. Additionally, cuboid dysfunction can interfere with normal function of the peroneal tendons and must be considered in dancers with peroneal tendinitis. Treatment of this unusual condition requires reduction of the cuboid with a squeeze technique after the hindfoot is mobilized and the forefoot is adducted.17

Midfoot injuries in the dancer present a significant treatment dilemma because of the prolonged healing time required for stability of the foot and the difficulty of restoring the mobility required for dancing. Midfoot injuries occur when the dancer lands in full pointe, with the posterior lip of the tibia resting and locked on the calcaneus. In this position the subtalar joint also is locked, and the heel and forefoot both are in varus. Because the ankle joint is relatively stable in full pointe, the forces at landing are transferred to the midfoot. Treatment of these acute injuries requires evaluation of both stability of the involved tarsometatarsal joints and amount of collapse of the longitudinal arch (see Chapter 5). Some diastasis may be acceptable if weight-bearing views do not demonstrate collapse of the longitudinal arch. Workup should include weight-bearing views, comparison weight-bearing views, and computed tomography (CT) scan if necessary.

The fifth metatarsal is a common area of injury for dancers. The most innocuous fracture is that of avulsion of the base of the fifth metatarsal. Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) is recommended only if the fracture fragment involves greater than 30% of the articular surface and is significantly displaced. The most typical fracture involves only the most proximal 1 cm of the bone and usually is associated with an ankle sprain. It can be treated with appropriate immobilization and progressive activity as healing permits. The Jones fracture (see Chapter 4) occurs by the mechanism of adduction of the fifth metatarsal, usually while the foot is plantarflexed. Because of the negative effects of prolonged immobilization, early operative management for these fractures at the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction is preferred.

When dancers perform the demi-pointe position, the foot is twisted and inverted and can incur an oblique or spiral fracture of the mid- to distal portion of the fifth metatarsal. This “dancer’s fracture” now has been shown to heal well with conservative and symptomatic treatment rather than ORIF.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree