Chapter 99 Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

A European Perspective

Isolated unicompartmental knee arthritis remains a challenging problem. Surgical management of unicompartmental knee arthritis includes conservative treatment such as arthroscopic débridement or high tibial osteotomy (HTO) and nonconservative treatment such as unicompartmental arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty (TKA).8,16 These procedures, however, have a finite lifespan in young and active patients and some concerns such as functional recovery and the possibility of returning to athletic activities should be considered.26,29 During the last decade, enthusiasm for the use of HTO has declined.2 It has been demonstrated that HTO remains an attractive conservative procedure to avoid knee prosthesis for patients younger than 50 years with a low-grade unicompartmental osteoarthritis and a varus knee. However, the HTO risk of failure increased dramatically for patients with osteoarthritis rated as Ahlback1 grade 2 or higher. In these cases, nonconservative treatment should be considered, even in younger patients. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), which has been performed since the 1970s, may provide better physiologic function and quicker recovery compared with total knee arthroplasty and preserves the bone stock in a patient in whom only one compartment of the knee is affected.11,12,21,32,40 Furthermore, patient satisfaction is greater because the knee feels more natural.

UKA has specific modes of failure, such as progression of the disease in the remaining compartments and polyethylene wear. In a recent survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons,10 UKA was the preferred procedure by 11.4% of surgeons for a 45-year-old active man and by 29.5% of surgeons for a 45-year-old active woman to manage a medial compartment arthritis, assuming a mechanical axis of 7 degrees of varus with an intact cruciate and mild patellofemoral symptoms. Improper patient selection combined with limited instrumentation and suboptimal designs may explain the less than satisfactory results originally published for UKA and the subsequent decreased interest, especially in the United States. Interest in UKA has been maintained in Europe since the first experience in the 1970s, and different new designs were developed in the 1980s.15,18,35,37 Since the early 1990s, new implant designs have been introduced, with reliable instrumentation, which makes the procedure as reliable as TKA. With proper patient selection and a more reliable surgical technique, the 10-year results of modern UKA are now available and show survivorship greater than 90% after 10 years of follow-up. The other potential advantage over tricompartmental replacement is preservation of the bone stock in the remaining compartment and preservation of the ligaments.4 Thus, modern UKA, as a conservative resurfacing arthroplasty of the knee, can preserve the cruciate mechanism, acting as a four-bar linkage guiding femorotibial movements.4 In vivo kinematics studies performed in patients implanted with a UKA have shown a femorotibial pattern similar to that observed in the normal knee.

The most important evolution in UKA during the last decade is so-called mini-invasive surgery (MIS).3,33 In regard to UKA, MIS is defined as the ability to implant components without an incision in the quadriceps tendon or the vastus medialis or lateralis, depending on the compartment to be replaced, and without everting the patella. Minimizing the trauma of the extensor mechanism should allow earlier walking and active muscle exercises. Repicci and Eberle34 proposed this mini-incision for the implantation of unicompartmental components as a resurfacing procedure using limited instrumentation. With the advances in instrumentation over the last 5 years, it is possible to perform partial knee arthroplasty with cutting guides fixed only on the replaced compartment, thus preserving the integrity of the unaffected tibiofemoral compartment. New worldwide interest in UKA is the result of the possibilities of fast recovery and minimal surgical morbidity permitted by MIS and improvement in UKA design allowing greater and safer motion capabilities, especially for active patients who are candidates for a UKA.8,9

Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: The European Experience

After the initial experience of Marmor in the United States in 1972, many variations of the Marmor Modular Knee were introduced in Europe at that time. Marmor published his own experience later, in the mid-1980s, but the concept of resurfacing the tibial and femoral sides of one femorotibial compartment gained great attention in several European countries.25 The principles of these resurfacing systems were to minimize saw cuts by adapting the femoral component to the condyle and using an polyethylene tibial component inlay cemented in the subchondral tibial bone while preserving the cortical rim. The St. Georges Sled, mostly used in northern Europe, was based on the same concept. The second generation of Marmor-like designs introduced a metal backing of the tibia to bring modularity to the procedure and distribute the weight-bearing forces more uniformly on the cut surface of the plateau. Although the initial results seemed satisfactory in terms of a more friendly surgical technique, wear failure of the tibial plateau was attributed mainly to the use of 6-mm-thick polyethylene. It is now recognized that the minimum thickness should be 8 mm for flat-bearing designs.6 Meanwhile, the Unicondylar Knee Prosthesis was used in the United States and Europe as an alternative to the Polycentric Knee or the Duocondylar design.21 Resurfacing both tibiofemoral compartments of the knee while preserving the cruciate ligaments represented the first form of the Oxford mobile-bearing system developed by Goodfellow and O’Connor in 1978.32 The concept was used for unicompartmental arthroplasty. It is based on a fully congruent mobile articulating surface, which aims to increase the area of contact and then reduce polyethylene wear. Measurement of retrieved bearings has shown a mean linear wear rate of 0.03 mm/yr or less (0.001 mm/yr) after normal function of the knee.5

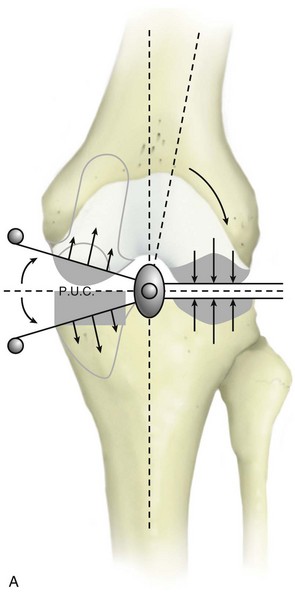

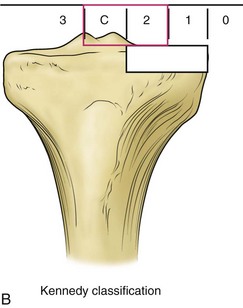

In France, Cartier and Cheaib12,13 introduced instrumentation specifically dedicated to UKA, promoting the concept that UKA was not a half-TKA and that the same type of persistent undercorrection of the deformity was suitable in opposition to the principle of TKA (Fig. 99-1A). These principles have been emphasized and accurately described by Kennedy and White22 in their paper describing the postoperative targets in terms of angles restoration after UKA (see Fig. 99-1B).

Figure 99-1 A, Diagram showing the mechanism of overcorrection leading to progression of osteoarthritis in the unreplaced compartment after UKA. B, These principles have been emphasized and accurately described by Kennedy and White22 in their paper describing postoperative targets in terms of angles restoration after UKA.

The cutting jig systems brought the same type of instrumentation as that used for TKA, with posterior and chamfer cuts of the femoral condyle based on intramedullary instruments. The advantage of this type of instrumentation was to provide a reproducible surgical technique, allowing the component to be placed perpendicular to the mechanical axis as previously determined on preoperative radiographs. Most of these designs have been used widely in Europe and the United States since the late 1980s, and long-term follow-up of the Brigham, Duracon, PFC Uni, and Miller-Galante is now available through the Swedish Registry.38 Independent publications also have reported survivorship comparable to that reported for TKA.2,11,15,27,40 Most of this experience was realized using cemented components, which remain the current standard for UKA in Europe. The first reported use of porous-coated designs was not encouraging, but hydroxyapatite coating has gained limited acceptance in some European centers.

Patient Selection

The indications for UKA are painful osteoarthritis (OA) or osteonecrosis limited to one compartment of the knee associated with a significant loss of joint space on radiographs.2,9,28,29 Results after UKA for osteonecrosis limited to one compartment of the knee (i.e., idiopathic or post-traumatic osteonecrosis) was comparable to those observed for OA at a mean of 12 years. Any type of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, is recognized as a formal contraindication for UKA because this can be a cause of rapid degeneration of the unreplaced compartments. Mild chondrocalcinosis, which is mostly a radiographic finding, may be accepted as an indication to perform UKA, in contrast to the productive chondrocalcinosis often associated with cyclic effusion of the knee.

Age and Weight

Age and weight may still represent debatable issues as indications for UKA because the procedure is often presented as an alternative to osteotomy or TKA. As noted, and according to the results of previously published series, we do consider the HTO as an attractive and efficient conservative procedure for patient younger than 50 years with a low-grade unicompartmental osteoarthritis and a varus knee.16 However, the HTO risk of failure increases dramatically for patients with osteoarthritis rated Ahlback grade 2 or higher, which is why in those cases we do consider UKA, even in younger patients.31 Regarding age and based on the comparative results at 10 years of UKA and TKA, Scott and associates40 considered that UKA now might assume a role in two groups of patients—middle-aged osteoarthritic patients (especially women undergoing a first arthroplasty) and osteoarthritic patients in their 80s octogenarians who are having their first and last arthroplasty. With survivorship studies of modern UKA comparable to those of TKA after the first decade, the selection process must be reconsidered; patients in their 60s and 70s would seem to have a greater chance of living out their lives with a TKA or UKA, which in any case would be easier to revise.8,14 We recently reported very good survivorship in the younger than 50 years, despite greater polyethylene wear than for older patients as observed also after TKA.29

Early reports of UKA considered obesity as a relative contraindication for UKA, but more recent studies have found no correlation between weight and outcomes. We agree with the idea that wear related is more to activity than to weight.6 Obesity itself is consequently not a contraindication.

Clinical Evaluation

The clinical examination of the knee before choosing UKA as a treatment option needs to focus on range of motion, with a minimum range of knee flexion of 100 degrees. A femoral contraction may be improved by only a few degrees after UKA and this should be recognized preoperatively. The clinical evaluation of the patellofemoral joint is also mandatory to seek out any type of anterior knee pain described by the patient during stair climbing and descending or during squatting. The stability of the joint must be evaluated carefully in the sagittal plane for the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and in the frontal plane using the results of specific tests. The unicompartmental implant fills the gap left by the worn cartilage, bringing the collateral ligament back to normal tension after the procedure. The clinical results of UKA using mobile-bearing meniscal or fixed-bearing prostheses and in vivo kinematics have highlighted the importance of a functional ACL for unicondylar knee replacement.4 The clinical outcomes for sedentary patients with a probable secondary distention of the ACL have confirmed that proper clinical function of the knee may be achieved in these low-demand patients using fixed bearings, despite ACL deficiency. For these patients, we concur with the findings of Hernigou and Deschamps,20 who studied the effects of posterior tibial slope on the outcome of UKA; they recommended avoiding a posterior slope more than 7 degrees when the ACL is absent at the time of implantation. For younger patients, a combined ACL-UKA surgery can be considered with good results in terms of pain and stability but with more limited range of motion as compared with isolated UKA (Fig. 99-2).

Radiologic Evaluation

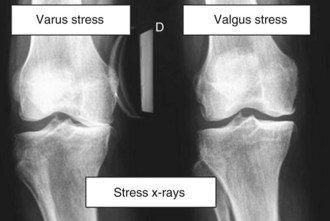

Our radiologic analysis systematically includes anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) views of the knee, full-length x-rays in bipedal and single-leg stance, varus and valgus stress radiographs, and skyline views at 30, 60, and 90 degrees of knee flexion.17 On full-length x-rays, the angle between the mechanical and anatomic axes of the femur can be calculated and reproduced during the procedure at the time of the distal femoral cut. This also evaluates any extra-articular bony deformity that cannot be corrected by the unicompartmental implant and searches for any femoral long hip stem that might require the use of a shorter intramedullary road or an extramedullary rod. Kozinn and Scott23 first, and later others, suggested that UKA should be limited to preoperative varus or valgus deformity of the lower limb less than 15 degrees and that greater deformities might represent a contraindication for UKA, because the correction of such deformities may require collateral ligament release, which should not be performed when doing UKA because that could lead to frontal femorotibial subluxation. It is also important to consider any important metaphyseal varus deformity of the proximal tibia (>7 degrees) because, in these rare cases, combined or staged HTO-UKA surgery can be considered (Fig. 99-3).

Varus and valgus stress x-rays, performed with the patient supine using a dedicated knee stress system, are important—first to assess the presence of full-thickness articular cartilage in the uninvolved compartment and second to confirm the full correction of the deformity to neutral (Fig. 99-4).17 In case of absence of insufficient or overcorrection of the deformity, this view indicates the need for soft tissue management and therefore the use of TKA. The lateral view of the joint confirms the absence of anterior tibial more than 10 mm, referencing the posterior edge of the tibial plateau, and shows that tibial erosion is limited to anterior and midportions of the tibial plateau. The height of the patella should also be analyzed because a patella baja will limit the exposure during MIS procedures.9

The radiographic analysis should ensure that there is no patellofemoral loss of joint space on skyline views at 30, 60, and 90 degrees of flexion. The presence of periarticular osteophytes may not be a contraindication for unicondylar replacement, and these osteophytes can be removed, even through a minimally invasive incision. Although the status of the patellofemoral joint is not a criterion of suitability for some, we now consider that the full loss of patellofemoral cartilage is a contraindication for performing a unicondylar remplacement. In these cases of associated wear in the medial and patellofemoral compartments, bicompartmental arthroplasty combining medial UKA and patellofemoral arthroplasty can be considered during the same procedure (Fig. 99-5).30 When there is a question regarding the status of the ACL following the clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful to confirm that the ACL is intact.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree