Recent advances in ultrasound technology are leading physiatrists to new understandings of pain sources, new treatment options, and the ability to guide soft tissue interventions. This article examines the role of imaging ultrasound in diagnosing soft tissue injury and disease that may respond to regenerative medicine techniques (known as prolotherapy) using injectants such as dextrose, morrhuate sodium, or platelet-rich plasma. The current state of ultrasound evidence for these interventions is reviewed. Case examples assist in understanding clinical applications that currently outpace the evidence base. Development of quantitative ultrasound measures to objectively evaluate soft tissue organization is discussed.

Imaging modalities in musculoskeletal medicine assist with diagnosis and ideally lead to an effective course of treatment that improves function at reasonable cost. Adoption of a specific imaging modality often depends on the intervention being considered. For example, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), assists physicians in distinguishing surgical versus nonsurgical lesions. However, MRI may also lead to unnecessary intervention in cases such as degenerative meniscal tears and lumbar disc degeneration. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography (MSKUS) is in its infancy and may be subject to the same type of misapplications. However, MSKUS has several advantages compared with MRI, such as low cost, high patient tolerability, real-time imaging to correlate with symptoms, and superior resolution in soft tissues. Borg-Stein and colleagues recently reviewed new concepts in assessing and treating musculoskeletal sports injury. This article summarized the benefits of MSKUS in evaluating soft tissue injury. The investigators also discussed injection therapies that are proposed to stimulate repair in these same tissues. A brief history may help in understanding the nomenclature of these interventions.

In the 1930s, Schultz reported on an injection technique that successfully induced tightening of loose temporomandibular joints; the solution injected was derived from the psyllium seed. In the 1950s, Hackett named this technique prolotherapy to imply proliferation of fibrous tissue. In his monograph, Hackett described the use of prolotherapy in the treatment of chronic low back pain. In the early 1990s, the monograph was updated with articles on proposed mechanism of action and use of prolotherapy (using other injectants, such as dextrose and morrhuate sodium) in essentially all joints of the body. Since those early reports in the treatment of temporomandibular joint syndrome and low back pain, the clinical use of prolotherapy has outpaced the research evidence for its use. Multiple texts have now been produced with detailed descriptions of prolotherapy technique that usually involves a diffuse pattern of injection and avoidance of antiinflammatory medications during treatment. The rationale for a diffuse injection pattern is based on the interconnected network of soft tissue (ie, fascia) that supports all joint structures. Rather than being a shotgun approach with the hope of injecting the correct structure, this technique is theorized to initiate a more vigorous response from the body to heal these fascial networks. These theories are discussed in more detail later in this article.

More recently, prolotherapy has been defined as the injection of growth factors or growth factor production stimulants, to promote growth and repair of normal cells and tissue. This global definition of prolotherapy is used in this article. A proliferant is any solution injected with the intent of growth or repair. The growth factors produced or provided with proliferant injection are those that are increased during the repair phase in soft tissue of various types, and thus connective tissue is the target for treatment. Linetsky and colleagues proposed the term regenerative injection therapy to describe treatments with this goal.

In the late 1990s, surgeons began adding platelet-rich plasma (PRP) to fibrin glue, forming a gel to place in surgical sites. The goal was to improve healing, anchoring of implantable hardware, and speed of recovery. In the early part of this century, individual physicians began injecting PRP as a prolotherapy agent (Michael Scarpone, MD, personal communication, 2010). The first published, nonsurgical report was a case series published in the podiatry literature. Foster and colleagues recently reviewed the basic science of PRP and its emerging application in surgical and nonsurgical sports medicine. In this article, Foster and colleagues report unpublished data on ultrasound-guided PRP injection of medial collateral ligaments in the knee and acute muscle tears. Crane and Everts believe the clinical use of PRP at this time has been most commonly applied by physicians previously trained in prolotherapy technique. We have a total of greater than 30 years clinical experience with dextrose and other nonautologous agents and 4 years experience using autologous PRP as an injectant.

Since 2005, the Hackett-Hemwall Foundation (a nonprofit organization supporting training and medical missions focused on prolotherapy) and the University of Wisconsin have sponsored an annual research forum focused on regenerative injection treatments. The mode of action for these therapies has been a major focus of discussion. Banks has proposed that the common end point of prolotherapy is formation of new collagen fibers. He believes that this primarily occurs through the induction of inflammation after injection of various substances: osmotic fluids, irritants, particulates, or chemotactic agents. However, growth factor effects can occur with neither an injectant nor inflammation. For example, clinical trials in which needling with injection of normal saline were used as a control have resulted in substantial and sustainable improvement in chronic pain, indicating that the process of needling is likely an active treatment. Growth factor stimulation by lipids released from cell membrane rupture and microbleeding with release of platelets have been proposed as potential mechanisms for such an effect. Not only is needling alone potentially an active treatment but inflammation may not be essential either, in that production of growth factors for soft tissue begins promptly after exposure of a variety of human cells to dextrose at levels of only 0.6%. Presentations at the Wisconsin meetings related to mechanism of action have varied from the original model of inflammation induction of the healing cascade, to focusing on the body’s response to percutaneous needling/tenotomy, perineural injection of hyperosmolar dextrose in fascial planes, sclerosing of abnormal neovessels in tendinopathy, partial neurolysis through the inclusion of phenol in solutions, dextrose-induced release of growth factors, and more direct forms of growth factor injection such as PRP.

Rabago and colleagues discuss many of these proposed mechanisms of action in their review of 4 injection therapies for lateral epicondylosis (LE). They conclude that “there is strong pilot-level evidence supporting the use” of dextrose/sodium morrhuate, polidocanol, autologous whole blood, and PRP injections in the treatment of LE. The common goal of these injection treatments is to stimulate a normal tissue repair cascade resulting in organized collagen fibers, not scar. The evidence base showing regeneration of tissue with these methods is small but growing at this point. Ultrasonography provides a low-cost method of evaluating soft tissue organization, function, and density more objectively. This article focuses on the use of ultrasound to identify soft tissue pathology, then objectively evaluates tissue repair after treatment with prolotherapy as defined earlier. As discussed elsewhere in this issue, abnormal fibrous tissue on ultrasound is generally less echoic, less organized/more heterogeneous (ie, loss of fibrillar pattern on longitudinal imaging), and thicker than normal fibrous tissue. If an intervention results in regeneration of normal tissue, the tissue should progressively return toward normal echogenicity, show return of normal fibrillar pattern, and return toward normal thickness.

The ultrasonography images in this article are from Dr Fullerton’s practice. Protocol for all follow-up imaging includes reproducing exact machine settings from the initial examination, then reproducing the exact slice and probe angulation of the previous examination as closely as possible, using bone landmarks as a guide.

Literature review with ultrasonography case examples

In 1993, Robert Schwartz, MD, a physiatrist, published the first known report using ultrasonography to evaluate tissue changes after prolotherapy. A 32-year-old woman had persistent hand and wrist pain 17 weeks after a fall on her outstretched left wrist. Her symptoms had not resolved with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), watchful waiting, or physical therapy. An ultrasound scan at that time revealed irregularity, discontinuity, and hypoechogenicity at the ulnar collateral and dorsal intercarpal ligaments. She was treated with a solution of 0.5 mL morrhuate sodium and 1 mL of 1% lidocaine injected at ligamentous entheses. Three treatments resulted in 75% long-term improvement and a return to a normal signal on ultrasound. At this time, most ultrasound evidence supporting prolotherapy is in the form of case reports, such as Dr Schwartz’s, or case series focused on specific diagnoses that are reviewed in this article. Large controlled studies using ultrasonography as an outcome measure require development of quantitative ultrasound tools that could be used in a blinded fashion, as discussed later in this article.

Elbow Tendinosis

Since 2001, South Korean researchers have published 21 articles on dextrose prolotherapy, and 3 of these reported use of ultrasonography in conjunction with prolotherapy. Although the full papers are published in Korean only, the abstracts, tables, and figures are available in English. Shin and colleagues reported that 71 of 84 patients with LE of the elbow showed statistically significant reductions in pain measured by visual analog scale (VAS). Forty-nine of these patients underwent MSKUS before treatment. Patients without clear partial tendinous tear on ultrasonography had more significant reduction in pain than those with a tear, indicating a possible predictive benefit of MSKUS. Park and colleagues reported on 12 common extensor tendons in 11 patients with LE of the elbow (tennis elbow). All had partial tears described as anechoic regions within the tendon; 1 was a full thickness but incomplete width tear. All patients were treated with dextrose prolotherapy (2–6 treatments) and had follow-up ultrasound 4.5 to 6.5 months after the initial ultrasound. All patients responded to treatment with reductions in pain on VAS. The most salient evidence of change on ultrasound was reappearance of a fibrillar pattern in the initially anechoic region in all 11 tendons. Kang and colleagues also reported on 12 LE patients with partial tears of the common extensor tendon. All were treated with 5 monthly injections of 15% dextrose. Five of the 12 had tears without evidence of tendinosis before treatment; none of these showed tendinosis on follow-up ultrasonography. Seven of the 12 had tears with tendinosis before treatment; 5/7 of these did not show tendinosis on follow-up examination. All showed appearance of fibrillar pattern in the anechoic regions after treatment. In the English language literature, Louis reported a case of common extensor repair on ultrasound after dextrose prolotherapy.

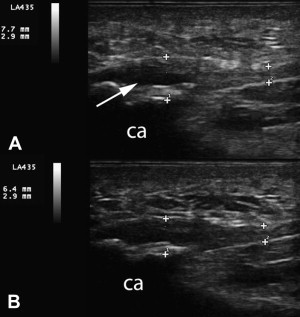

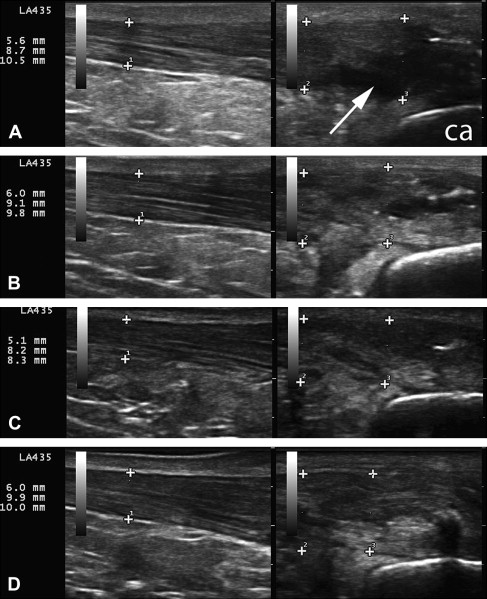

We see similar changes on ultrasonography in our clinics; an example has been published in a sports medicine text. An example of common flexor tendon tear in the elbow is included here ( Fig. 1 ). The patient is a 40-year-old man with 9-year history of medial elbow pain. He retired early from professional baseball after developing problems with throwing accuracy. During his career, he was treated with 4 corticosteroid injections for medial epicondylitis diagnosed by MRI; these were not successful. In our clinic, he received 3 treatments with 15% dextrose to the common flexor tendon and ulnar collateral ligament. The tear reduced significantly in size and developed a fibrillar pattern within the anechoic region. The patient reported significant reduction in pain and returned to weight lifting, which he had not been able to tolerate before treatment.

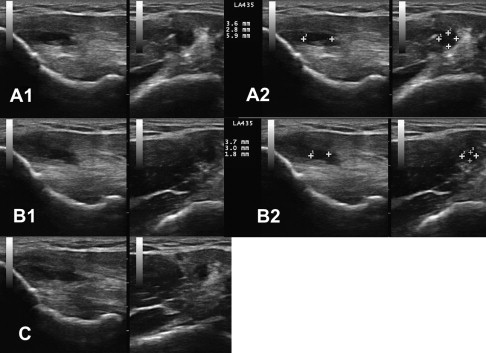

In 2006, Mishra and Pavelko published the first study on the use of PRP injection in chronic tendinopathy. This study is summarized elsewhere in this issue. No imaging before or after treatment was reported and ultrasound guidance was not used. A case of PRP treatment in severe LE is included in Fig. 2 . This 45-year-old man had a history of bilateral chronic LE resulting in surgical tenotomy on the right and multiple steroid injections bilaterally. He was treated with 1 dextrose prolotherapy followed by 2 PRP treatments with almost complete resolution of symptoms; he returned to playing golf for the first time in 2 years. The clinical improvement in this patient has now been maintained for 8 months. Movie 1 shows the first injection of PRP confirming capsular tear as the hyperechoic PRP flows through the tendon into the radiocapitellar joint. Clinical observations such as this illustrate the potential of ultrasonography to expand understanding of pathophysiology in tendinopathy.

Osteitis Pubis

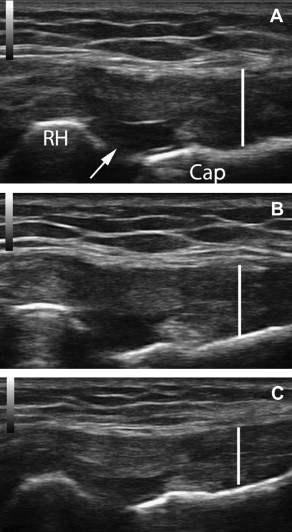

In 2005, Topol and colleagues reported a consecutive case series involving elite Argentinean athletes with chronic groin pain (6–60 months). Athletes were diagnosed with osteitis pubis, abdominal tendinopathy at the pubic bones, and/or hip adductor tendinopathy based on history, clinical examination, and response to lidocaine blockade at the corresponding entheses. Athletes received a mean of 2.8 treatments of 12.5% dextrose with 0.5% lidocaine. Twenty-two of 24 athletes who had been unable to participate in their sport returned to full play; 20/24 had complete resolution of symptoms with full sport. The same investigators extended the case series to 72 athletes by 2008. Sixty-six of 72 returned to unrestricted sports activity with minimum follow-up of 3 years after completion of treatment. No imaging was included in these studies. An example of pre- and posttreatment images of the pubic symphysis is included in Fig. 3 . The patient is a 55-year-old man with a 3-year history of pubic/groin pain and pubic symphysis crepitus after impact between the pubic symphysis and a saddle horn when his horse stumbled. After 3 treatments with dextrose/morrhuate sodium injection at the superior pubic ligament, his VAS reduced from 6 to 0.

Patellar Tendinopathy

In 2008 Volpi and colleagues evaluated a single PRP treatment combined with structured rehabilitation protocol in chronic patellar tendinosis. A total of 10 tendons in 7 athletes were treated and completed follow-up. Ultrasound was used for guidance in the injection of 3 mL of autologous PRP spread between 5 and 8 locations using a 22-gauge needle. Eight of the 10 tendons examined with MRI at follow-up showed “signs of reduced irregularity at the level of the tendon insertion and the preinsertional eodema” compared with pretreatment MRI findings. Ultrasound was not used in pre- or posttreatment evaluation. All subjects completing the study showed a considerable (more than 35-point) improvement in the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment (VISA) score, a measure of function and sports performance.

In 2009, Kon and colleagues published a pilot study using a series of 3 PRP treatments followed by rehabilitation for jumpers knee. Twenty male athletes had pretreatment imaging with MRI or MSKUS to confirm the diagnosis. They received 5 mL of autologous PRP at each treatment with 15 days between each session. At 6-month follow-up, 16/20 (80%) were satisfied with treatment and showed statistically significant improvements in SF-36 parameters and sports activity ( P = .002–0.0005); 4/20 (20%) did not improve.

Ultrasonographic follow-up after prolotherapy for patellar tendinopathy has been reported in 2 case reports; both included pre- and posttreatment ultrasonography. One included MRI confirmation of the improvements on ultrasound (ie, improved fibrillar pattern and echogenicity, reduction in tear, resolution of patellar edema) after treatment with 15% dextrose (×3) and 1 treatment with Ongley solution (phenol, glycerin, glucose). Louis showed significant reduction in neovascularization after injection of 25% dextrose.

Achilles Tendinopathy

In 2005, Lazzara reported repair of an Achilles tendon rupture using dextrose/morrhuate sodium prolotherapy. The 26-year-old female soccer player was initially diagnosed with severe calf sprain and treated with cast in 30° plantar flexion. MRI at day 43 after the injury revealed a complete tear of the Achilles tendon with a 1.1-cm gap. She refused surgical repair and presented to Dr Lazzara requesting a trial of prolotherapy. She received treatment every other week for a total of 8 treatments using dextrose and morrhuate sodium and returned to sports without pain or limitation. Repeat MRI after the sixth treatment showed “no abnormality distal to the musculotendinous junction.” The pre- and posttreatment sagittal MRI images do show improved tendon signal, but do not show the same slice of tendon. The pretreatment ultrasound image does not show a clear tendon tear. Pre- and posttreatment ultrasound images lack scale or bony landmarks to orient the viewer, making the imaging unconvincing.

In 2007, Sanchez and colleagues reported on the use of PRP to facilitate healing after surgical repair of ruptured Achilles tendon. Six athletes underwent open suture repair with addition of a preparation rich in growth factors (PRGF), another term for PRP. Those were compared retrospectively with matched controls (same mechanism of injury, age, gender, activity) undergoing the repair without addition of PRGF. Each group received oral diclofenac as needed after the procedure. Ultrasonographic follow-up was performed on each group. The PRGF group showed less increase in cross-sectional area of the tendon, which indicates more tightly packed collagen fibers. The PRGF group had no wound complications, recovered range of motion earlier, and returned to gentle running and training sooner than the control group.

De Vos and colleagues recently examined the effects of 1 PRP treatment compared with saline injections under ultrasound guidance in 54 patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Both groups improved significantly; however, there were no differences between the 2 groups. Patient selection was a significant limitation of this study. Patients were not required to try standard-of-care treatment (eccentric exercise) before injection; and all patients performed eccentric exercise after injection. Insertional Achilles tendinopathy was excluded; although this type of injury responds well in our experience, as seen in the example discussed later. Ultrasound was also not used to describe the extent of tendinopathy; there are no descriptions of tears, neovascularization, or extent of inhomogeneous regions. The saline injection should not be considered a placebo because it involved multiple intratendinous insertions, and the body responds to needle tenotomy and stretching of fibers from volume injection. The only conclusion from this study is that injections do not need to be given before trying noninvasive, standard-of-care treatment in patients with proximal Achilles tendinopathy.

In 2007, Maxwell and colleagues reported on 36 consecutive patients with chronic Achilles tendinopathy treated with ultrasound-guided injection of hyperosmolar (25%) dextrose. Mean percentage reduction in pain VAS was significant: 88.2% at rest, 84% with daily activity, and 78.1% with sport or other high-level activity. This prolotherapy study is the largest that has included before and after ultrasonography as an outcome measure. The investigators reported a highly significant ( P = .0007) improvement (reduction) in mean tendon thickness, from 11.7 to 11.1 mm, between initial and follow-up ultrasounds. Posttreatment tendons with anechoic clefts or foci reduced by 78%. Neovascularity decreased in 55% of tendons; it was unchanged in 33% of tendons. Four tendons had no neovascularity before or after treatment. Echogenicity was unchanged in 82% of tendons and improved in 18% (this finding is discussed later). Twelve-month phone follow-up (mean) was conducted in 30 available patients: 20 were still asymptomatic, 9 had mild symptoms, and 1 had moderate symptoms.

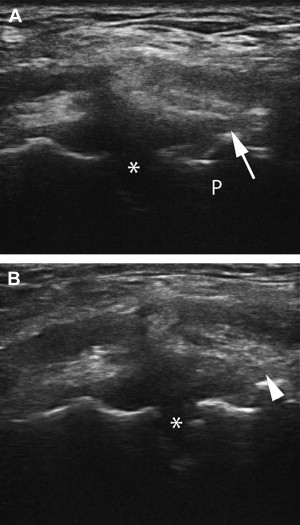

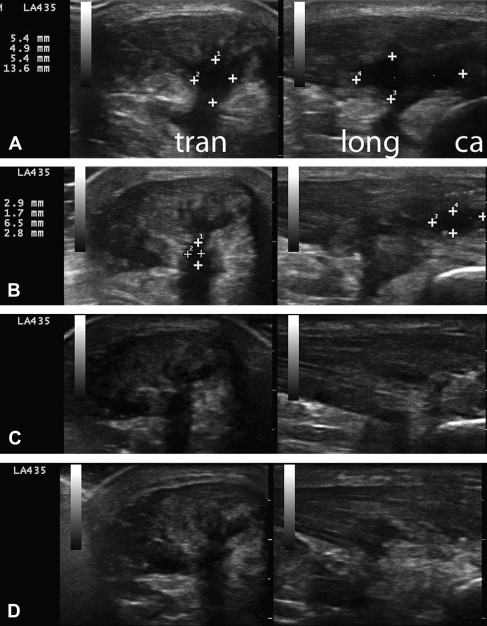

Fig. 4 A to C and Fig. 5 A to C show tissue changes after dextrose prolotherapy in a 67-year-old man with insertional, calcific Achilles tendinopathy and a partial tear. These images show significant, but not complete, repair of a partial tear in the setting of advanced tendinosis using 25% dextrose prolotherapy delivered via a 27-gauge needle. Movie 2 (from the first of 5 dextrose treatments) shows a transverse view of the tendon with injection at the tear. Hyperechoic debris filters from within the intact portion of the tendon through the tear. These images illustrate the importance of imaging in 2 planes. Fig. 4 (longitudinal imaging only) gives the impression that the tear is fully repaired after 3 treatments with 15% dextrose (images A to B). However, these sagittal images through the tendon are not of the same slice. Fig. 5 , which includes transverse images, shows that the tear is reduced, but not completely resolved. Fig. 4 D and Fig. 5 D show additional tissue changes after tenotomy using a 16-gauge needle with injection of PRP. Movie 3 is a longitudinal view at the Achilles insertion, showing the needle tenotomy with injection at regions of calcification. The patient elected for this more aggressive treatment of calcific regions in an attempt to resolve all symptoms. Now, 8 months after percutaneous tenotomy with PRP, he is pain free with all activities.

Plantar Fasciitis/Fasciosis

In 2004, the podiatrists Barrett and Erredge reported a case series of ultrasound-guided, autologous PRP injection for plantar fasciitis. Nine patients with diagnosis of plantar fasciitis (fasciosis) were recruited; all had “significantly thickened and hypoechoic plantar fascia” on MSKUS using high-frequency linear array transducer. Under ultrasound guidance, 3 mL of PRP was injected at the most hypoechoic regions. Sequential ultrasound scans were obtained at 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 3 months. All 9 patients showed improvement on ultrasound with increased signal intensity and an average reduction in thickness of more than 2 mm. Six of the 9 obtained complete resolution of symptoms 2 months after 1 treatment. One of these was dropped from the study after receiving a subsequent steroid injection. Two of the 9 had complete resolution of symptoms after a second treatment with PRP. One of the 9 had occasional pain when walking barefoot.

Louis included an example of plantar fasciitis with partial tear in his review article of musculoskeletal ultrasound intervention. Ultrasound before dextrose prolotherapy shows the classic appearance of plantar fasciitis with partial tear at the deep insertion. The image after treatment shows a thinner plantar fascia with improved echogenicity, improved fibrillar pattern, and almost complete resolution of the tear. This concurs with our clinical experience using dextrose injection to treat plantar fasciopathy. Fig. 6 shows an example of tissue changes in a 58-year-old woman with a 2-year history of symptomatic plantar fasciopathy unresponsive to standard-of-care treatment. After 3 treatments with 25% dextrose, her VAS dropped from 7 to 0 with all activities.