Diagnostic ultrasound has been and is becoming an increasingly valuable tool for the orthopedic surgeon in the evaluation of the musculoskeletal system. Ultrasound has been found to be an extremely important tool in the effective evaluation and efficient management of rotator cuff disorders. It helps to educate surgeons regarding a patient’s shoulder, patients regarding their own shoulder, and surgeons regarding the shoulder in general. All of the principles acquired through shoulder ultrasound can be applied to the entire musculoskeletal system.

Orthopedic surgeons have used the findings of diagnostic ultrasound to help in the evaluation and management of a wide variety of musculoskeletal disorders for many years. Studies report ultrasound diagnosis of problems in the shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand, hip, knee, calf, ankle, and foot and the use of ultrasound to help in the injection of multiple joints. Internationally, ultrasound has been used by orthopedic surgeons for some time. More recently in the United States, ultrasound has found its way into the orthopedist’s office. Much of the use has involved the shoulder and evaluation of the rotator cuff; however, any of the previously described joints can be evaluated by the orthopedic surgeon. Lessons learned from the shoulder can easily be translated to these other anatomic structures.

E. A. Codman, in the early 1900s, recognized the importance of the efficient and effective evaluation and management of shoulder disorders to society and industry. In fact, he felt that 100 neglected rotator cuff tears cost more to society than the cost of his schooling and medical education, his inheritance, and all of his professional fees combined. He compared an acute tear of the rotator cuff to an acute appendicitis and stated that the purpose of his classic 1934 monograph regarding the shoulder was to “…teach physicians how to recognize rotator cuff tears immediately and rush the patient to a competent surgeon as promptly as if the patient had a fractured arm.” In-office diagnostic ultrasound offers the kind of efficient and effective evaluation of the rotator cuff that Codman believed was so valuable. These diagnostic principles again can be applied to other anatomic structures and clinical problems.

Although recognizing the importance of the rotator cuff to the patient and society, and Codman’s call for urgent diagnosis, the authors have found the use of ultrasound in the office to greatly enhance the effective and efficient approach to the evaluation and management of rotator cuff disorders. Furthermore, ultrasound of the shoulder has enhanced the authors’ overall practice of orthopedics in multiple ways. Ultrasound is integrated as seamlessly as possible into the clinic setting when used as an extension of the physical examination. As a diagnostic tool it educates surgeons regarding the anatomic details of a patient’s shoulder. It is also very important in educating patients about their shoulder and involves patients in their own care.

Ultrasound evaluation

The authors’ approach to the shoulder and all other clinical presentations focuses on the principles of Matsen and colleagues, who advocate proper evaluation of the disorder followed by appropriate management, as opposed to specific “diagnosis and treatment.” Diagnostic ultrasound is an excellent modality to incorporate into the overall evaluation of the shoulder. The normal shoulder has excellent strength and stability through a large range of smooth motion. Therefore, evaluation of a shoulder disorder includes a determination of whether the patient is experiencing shoulder stiffness, weakness, roughness, instability, or some combination of these symptoms.

This evaluation begins with simple observation, viewing the patient from the front and the back, looking for any evidence of asymmetry. Shoulders are also compared during active forward elevation to evaluate scapulothoracic kinematics. Both shoulders are always examined starting with the less-symptomatic one first. Motion should then be documented with attention to how the motion relates to the capsule of the shoulder. This assessment includes not only the maximum level of shoulder elevation but also external rotation with the arm adducted (anterior/superior capsule), external rotation in abduction (anterior/inferior capsule), internal rotation in abduction (posterior/inferior capsule), cross-body adduction (posterior capsule), and internal rotation behind the back (posterior/superior capsule). The smoothness of the glenohumeral joint and the subacromial space is then evaluated. Strength of three heads of the deltoid is tested, as is external rotation at the side (infraspinatus), internal rotation with the arm adducted (pectoralis major), abdominal press test (subscapularis), and supraspinatus testing with the arm away from the body. Stability is also evaluated.

After the physical examination, radiographs are obtained, with specific images ordered based on the problem presented, but always including orthogonal views. After this evaluation, a management plan is formulated with the patient’s input. If appropriate nonoperative management failed to resolve the problems and the rotator cuff is an area of concern, then documentation of rotator cuff integrity is indicated. Current options for this evaluation include arthrogram, CT arthrogram, MRI (with or without arthrogram), and ultrasonography. Arthrogram and CT arthrogram are invasive and not optimal for imaging the rotator cuff, especially in the presence of a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear.

Generally, MRI is considered the gold standard for soft tissue imaging, including the rotator cuff. Early studies have noted 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity for complete tears. With the preponderance of MRI scanners, the examination and accuracy of the report certainly has a wide range in quality. Subscapularis tears are notoriously evaluated poorly by MRI. Ultrasound was shown early to give excellent specificity and sensitivity when evaluating the rotator cuff. It allows for a bilateral, dynamic evaluation of the patient’s shoulders and is much less expensive than MRI. However, not everyone has been able to reproduce these results, with wide variability reported ( Table 1 ). To have consistent results, orthopedists must have a real dedication to the modality and adherence to a rigorous protocol. The authors have been able to reproduce the results of Mack and colleagues and others by integrating ultrasound into their orthopedic clinic. It is integrated in patient evaluation as an extension of the physical examination.

| Author | Year | No. of Patients | Verification | Full-Thickness Tears | Partial-Thickness Tears |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farrar et al | 1983 | 48 | 91%; 76% | ||

| Mack et al | 1985 | 72 | Arthrography | 93%; 97% | |

| Mack et al | 1985 | 47 | Surgery | 91%; 100% | |

| Middleton et al | 1985 | 39 | Arthrography | 93%; 83% | |

| Middleton et al | 1986 | 106 | Arthrography | 91%; 91% | |

| Brandt et al | 1989 | 62 | Arthrography | 68%; 90% | |

| Brandt et al | 1989 | 38 | Surgery | 57%; 76% | |

| Soble et al | 1989 | 75 | Arthrography | 92%; 84% | |

| Soble et al | 1989 | 30 | Surgery | 93%; 73% | |

| Miller et al | 1989 | 57 | 58%; 93% | ||

| Burk et al | 1989 | 10 | Surgery | 63%; 50% | |

| Vick & Bell | 1990 | 81 | Arthrography (79); surgery (2) | 67%; 93% | |

| Drakeford et al | 1990 | 50 | Arthrography | 92%; 95% | |

| Kurol et al | 1991 | 58 | Surgery | 67%; 74% | |

| Hedtmann & Fett | 1995 | 1227 | Surgery | 97.3%; 94.6% | 91%; 94.6% |

| Van Holsbeeck et al | 1995 | 52 | Surgery | 93%; 94% | |

| Van Moppes et al | 1995 | 41 | Arthrography & surgery | 86%; 91% | |

| Chiou et al | 1996 | 157 | Arthrography | 92%; 97.2% | |

| Alasaarela et al | 1998 | 20 | Surgery | 83%; 57% | |

| Read & Perko | 1998 | 42 | Surgery | 100%; 97% | 46%; 97% |

| Fabis & Synder | 1999 | 74 | Surgery | 98.2%; 90% | 50%; 96.3% |

| Roberts et al | 2001 | 24 | Surgery | 80%, 100% | 71%, 100% |

The authors’ protocol includes a thorough history, physical examination (bilateral shoulder examination), plain radiographs, and, if the indications are present (ie, objective findings of rotator cuff pathology on physical examination in a patient for whom appropriate nonoperative management failed), ultrasonic evaluation of the shoulder. The technique is a modification of that described by Mack and colleagues. It is a dynamic examination in six planes using active muscle contraction against resistance, and functional evaluation of shoulder elevation. Bilateral examinations are always performed, evaluating the less symptomatic shoulder first to define the anatomy and allow patients to experience the examination and realize what normal pressure of the probe should feel like. Furthermore, it educates patients on the anatomy of their own shoulder. Examinations are performed within the flow of the normal clinic day and can be completed in approximately 10 minutes (not including postexamination consultation).

The examiner and patient are positioned on rolling/rotating stools, with the examiner sitting at an angled position from the patient so that both can visualize the screen ( Fig. 1 ). Positions are switched when evaluating the opposite shoulder. The sequence of the examination is based on efficiency and convenience and is always followed with an assistant present to enter data directly into the database ( Box 1 ).

- •

Transverse view of the biceps tendon

- •

Longitudinal view of the subscapularis (recording tendon thickness and evaluating the dynamic movement of the tendon under the coracoid process)

- •

Transverse view of the supraspinatus tendon (recording tendon thickness)

- •

Longitudinal view of the infraspinatus tendon (recording tendon thickness), posterior glenoid, and labrum

- •

Longitudinal view of the infraspinatus muscle belly (recording thickness and evaluating contractility)

- •

Longitudinal view of the biceps tendon

- •

Transverse view of the subscapularis tendon

- •

Longitudinal view of the supraspinatus tendon with the arm at the side (static and dynamic evaluation with elevation, grading the clearance of the greater tuberosity under the acromion)

- •

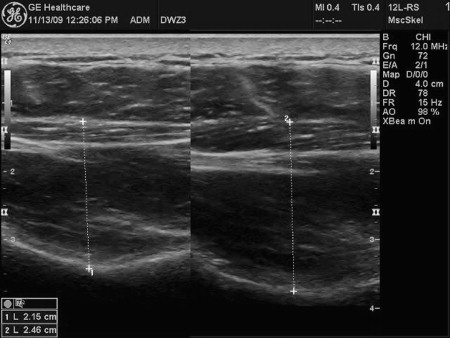

Longitudinal view of the supraspinatus muscle belly (recording belly thickness at rest and with contraction) (see Fig. 2 )

- •

Longitudinal view of the supraspinatus with the arm in internal rotation and extension, and transverse view of the supraspinatus with the arm in internal rotation (recording tendon thickness)

Throughout the examination patients are encouraged to provide feedback about any tenderness they may experience, especially compared with the asymptomatic or less symptomatic shoulder. This disclosure is important when ruling out an entity such as biceps tendonitis or if specific tenderness is present when imaging directly over an abnormality in a rotator cuff tendon. When evaluating the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscle bellies, the quality of the muscle is noted and can easily be compared with that of the overlying deltoid and trapezius muscles, respectfully. The potential space available for the individual muscle is measured, and as the muscle is loaded the amount of tissue that is actually contracting is observed. The thickness of this contractile tissue is then measured both at rest and during contraction ( Fig. 2 ). Therefore, both qualitative and quantitative data on the muscle bellies are recorded. Comparison with the less-symptomatic shoulder allows atrophy of the muscle and the contractility of the remaining atrophic tissue to be determined.

Criteria used for determining partial- and full-thickness rotator cuff tears are based on previously reported criteria and observations made during ultrasounds and confirmed at surgery. Criteria for full-thickness tears include

A focal thinning of the rotator cuff tendon and complete nonvisualization of the rotator cuff tendon

Focal discontinuity in homogenous echogenicity of the rotator cuff tendon without focal thinning

Inversion of the superficial bursal contour and hyperechoic material in the tendon location that fails to move with the humeral head during real-time dynamic imaging.

Criteria for partial-thickness rotator cuff tears include

A hypoechoic discontinuity within the tendon with the lesion involving either the bursal or articular side of the tendon or a mixed hyperechoic/hypoechoic region within the tendon caused by separation of the torn edge from the rest of the tendon

Confirmation of the symptomatic nature of partial- and full-thickness rotator cuff tears is enhanced by patient reports of tenderness when imaging over the sonographically defined defect.

Another criterion the authors use to determine rotator cuff tendon pathology involves the limitation associated with pain or roughness on clearance of the greater tuberosity under the acromion during active glenohumeral elevation. This criterion has been found to be highly specific in determining rotator cuff tendon pathology, although not as sensitive as other criteria. The authors also adhere to the two-criteria model described by Hedtmann and Fett, in which a defect is only diagnosed if a criterion is reproducible in different joint or transducer positions. Diagnosis is also confirmed if a second type of criterion (eg, static and dynamic criterion) is present in the same position.

By using the above criteria and adhering to the described rigorous protocol of patient evaluation (history, physical examination, and plain radiographs) combined with proper indications, the authors have had excellent success using ultrasound to evaluate the integrity of the rotator cuff.

Understanding the potential pitfalls that can lead to suboptimal results is also important. One of the most common pitfalls involves the misinterpretation of normal anatomy, which can occur in older patients in whom the echogeneity of the rotator cuff is similar to that of the overlying deltoid muscle. Anterior to the supraspinatus, the hyperechoic biceps tendon and the hypoechoic area just posterior to it may be misinterpreted as an abnormality. Other examples include the normal thinning of the posterior supraspinatus and the mild inhomogeneity of the rotator cuff tendons. Soft tissue abnormalities such as the inferior subluxarion of the humeral head in a patient with deltoid dysfunction can lead to difficulties in sonographic shoulder evaluation, as can bony abnormalities (eg, calcific nodules). Technical limitations of ultrasound, as shown through inability to image the supraspinatus because of the overlying acromion, also leads to difficulty in imaging the rotator cuff and a potential for misinterpretation. The impact of an overlying acromion varies among patients and can be accentuated in the face of capsular tightness.

Awareness of these potential pitfalls is the first step in avoiding them and maximizing the effectiveness of shoulder ultrasound. This strategy can also be applied to the imaging of other anatomic structures. Most important in maximizing imaging and avoiding pitfalls is the examiner having an excellent three-dimensional understanding of the anatomy being imaged. No one has a better understanding of shoulder anatomy than a physician/surgeon who is either examining or performing surgery on the shoulder consistently. Also important is proficiency at imaging with ultrasound, which is something gained through performing hundreds of examinations.

Imaging the shoulder with ultrasound is very similar in principle to arthroscopic examination of the shoulder. In arthroscopy, as with ultrasound, a specific protocol of examination should be followed, with all structures evaluated in a specific sequence. Basically the image can be altered and potentially enhanced in three ways: (1) changing the position and angle of the scope, (2) rotating the angle of view of the arthroscope, and (3) altering the position of the shoulder. These techniques are similar to those that can be used in ultrasound, in which the position of the probe or its angle of imaging can be changed, the probe can be rotated to image either transversely or longitudinally, or the position of the shoulder itself can be modified. When learning to perform shoulder arthroscopy, surgeons can use the biceps tendon as a structure of orientation. If at any time during the procedure the surgeon is confused or seems “lost,” the biceps tendon can easily be “found” and the surgeon reoriented. Similarly, with ultrasound of the shoulder, the transverse view of the biceps tendon can always be found relatively easily, providing an opportunity for the examiner to become reoriented.

Another tactic for avoiding pitfalls is using the asymptomatic or less-symptomatic shoulder as a control. This technique helps with individual variations in the echogeneity of the rotator cuff and surrounding structures. Reviewing plain films before ultrasonic examination is mandatory and helps avoid problems associated with bony abnormalities and inferior humeral head subluxation. The position of the shoulder must be maximized to enhance optimal visualization of the rotator cuff tendon. Specifically, the shoulder is placed in internal rotation and extension to pull the supraspinatus attachment out from under the overlying acromion. This positioning also places tension on the supraspinatus, pulling it out to length and thus accentuating any potential defects at its attachment.

One of the major strengths of ultrasound is that the interpreter is performing the examination and the patient is awake and alert during the examination, and therefore capable of following commands. This fact is extremely important given the dynamic nature of ultrasound. The patient’s shoulder can be evaluated during both passive and active motion. The patient can also perform muscle contraction against resistance, allowing the muscle bellies and tendons to be visualized. The patient can provide feedback regarding any tenderness when imaging over areas of abnormalities, and if any question arises, a structure can be reimaged from a different position and the opposite shoulder can be reimaged for comparison. All of these strategies can be used to maximize the effectiveness of the ultrasound examination and minimize pitfalls leading to misinterpretations. Although the shoulder has been specifically discussed, these strategies can be applied to any anatomic structure visualized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree