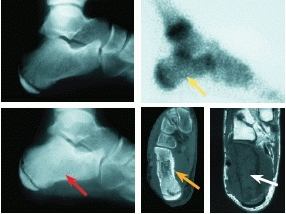

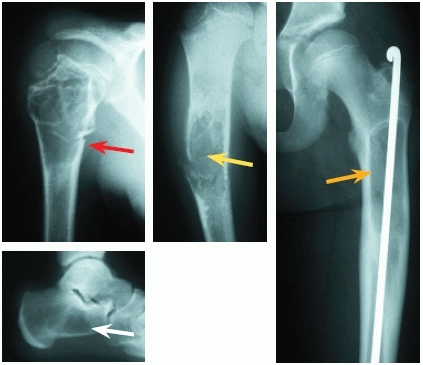

A Presentations of tumors in children The common modes of presentation are with a mass, as in osteochondroma (green arrow); with pain, as in osteoid osteoma (orange arrow); with a pathologic fracture, as in osteosarcoma (red arrow); or as an incidental finding, such as this small nonossifying fibroma (yellow arrow).

History

Tumors usually present as a soft tissue mass, produce pain, or cause disability. How long a mass has been present is often difficult to determine from a history. Frequently, a large lesion, such as a slow-growing osteochondroma, is not noticed until shortly before the consultation. The family may incorrectly conclude that the tumor had grown quickly.

Pain

is a more reliable indicator of the time of onset of a tumor. Inquire about the onset, progression, severity, and character of the pain. Night pain is common for both malignant tumors and some benign lesions, such as osteoid osteoma. Malignant lesions produce pain that increases over a period of weeks or months. Night pain in the adolescent is especially worrisome and should be evaluated first with a conventional radiograph. An abrupt onset of pain is usually due to a pathologic fracture. Such fractures most commonly occur through bone cysts typically found in the humerus and femur.

Age

of the patient is helpful. A bone lesion in a child under age 5 years is likely to be due to an infection or eosinophilic granuloma. Giant cell tumors and osteoblastomas occur in the late teen period.

Race

is notable, as blacks seldom develop Ewing sarcoma.

Examination

The initial examination is usually performed for a mass or pain. Some lesions, such as osteochondromas, are usually multiple. Look for asymmetry, deformity, or swelling. Palpate for masses. If a mass is present, measure its size, assess for tenderness, and note any associated inflammation. Malignant tumors are typically firm, are nontender, and may produce signs of inflammation.

Imaging

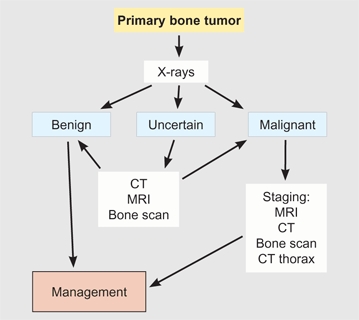

Order imaging studies with a plan in mind [A]. Start with good-quality radiographs. Conventional radiographs remain the basic tool for diagnosis. Consider several features in assessment.

A Flowchart for imaging primary bone tumors

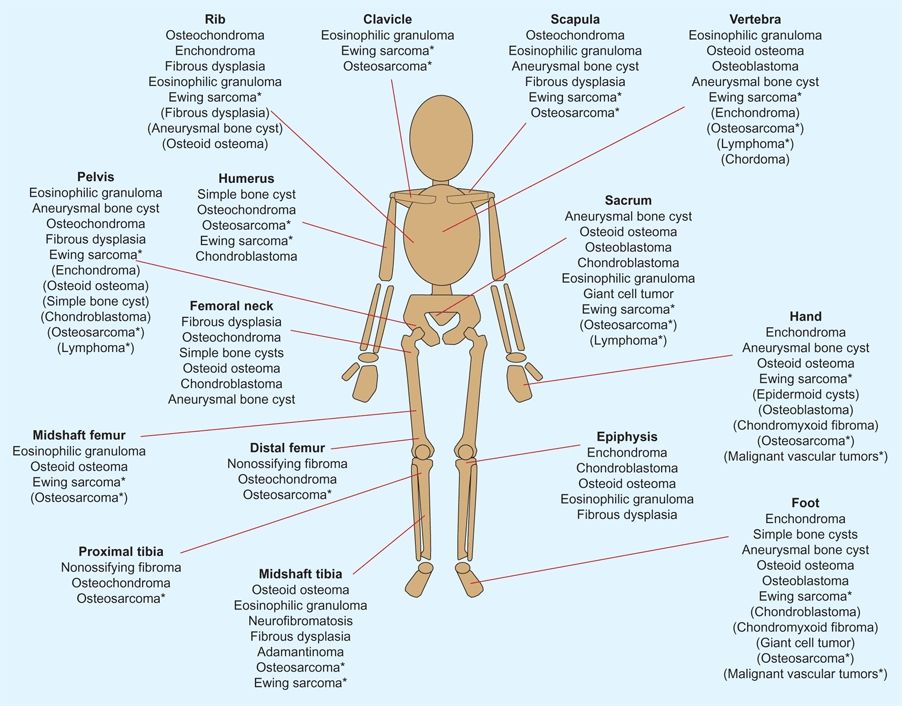

Location

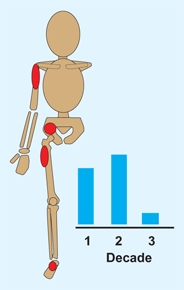

Lesions tend to occur in typical locations both with respect to the bone involved [B] and the position in the bone [A, next page].

B Tumor types per site Less common tumors at each site are in parentheses. Asterisks (*) indicate malignant tumors. Based on Adler and Kozlowski (1993).

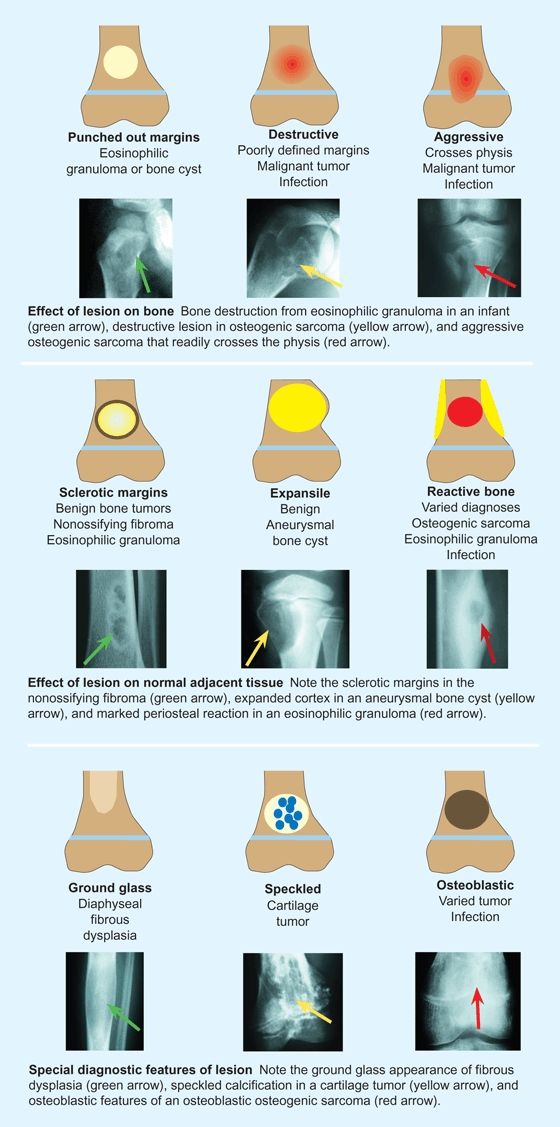

Effect of lesion

Note the lesion’s effect on the surrounding tissue [C, next page].

Effect of lesion on bone

Sharply punched out lesions are typical of eosinophilic granuloma. Osteolytic lesions are typical of most tumors; few are osteogenic on radiographs.

Effect on normal adjacent bone

is useful in determining the invasiveness of the lesion. An irregular, moth-eaten appearance suggests a malignant lesion or an infection. A lesion that expands the adjacent cortex is usually benign and typical for aneurysmal bone cysts.

Diagnostic features

suggest the aggressiveness of the lesion. Sclerotic margination suggests that the lesion is long-standing and benign. Periosteal reaction suggests a malignant, traumatic, or infectious etiology.

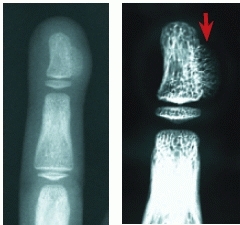

Special imaging

Consider special types of conventional radiographs, such as for soft tissue or bone detail [B, next page].

A Typical locations for various tumors Note the location in the epiphysis, metaphysis, or diaphysis.

C Diagnostic features by conventional radiography Note the effect of the lesions on bone (top), the effect on normal adjacent tissues (middle), and special diagnostic features (bottom).

B High-resolution radiographs Compared to conventional radiography (left), note the increased bony detail shown by the high-resolution radiograph (red arrow).

Special studies

may be essential to establish the diagnosis [A].

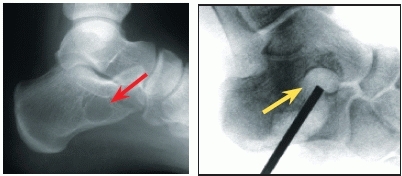

A Evaluation by imaging This child had foot pain and a negative radiograph (upper left). A month later, the patient was seen again because of increasing night pain. At that time, a bone scan showed increased uptake (yellow arrow), the radiograph showed increased density of the calcaneus (red arrow), a CT scan showed erosion of the calcaneus (orange arrow), and MRI showed extensive marrow involvement (white arrow). Ewing sarcoma was suspected by these findings.

CT scans

are useful in assessing lesions of the spine or pelvis. Whole lung CT studies are highly sensitive for pulmonary metastases.

MRI

is the most expensive diagnostic tool and is limited in young children due to the need for sedation or anesthesia. However, it is the most sensitive in making an early diagnosis and excellent for tissue characterization and staging of tumors, so it should be made of all malignant soft tissue and bone tumors.

Bone scans

are the next most useful diagnostic tools. These scans are helpful in determining whether a lesion is solitary or other lesions are present. The uptake of the lesion is important to note. A cool or cold scan suggests that the lesion is inactive, and only observation may be necessary. Warm scans are common in benign lesions. Hot scans suggest that the lesion is very active and that it may be either a malignant or benign lesion, such as an osteoid osteoma. Biopsy or excision is required.

Positive emission tomography

PET scans are expensive but useful in evaluating malignant soft tissue and bone tumors, and especially in assessing the response to chemotherapy.

Laboratory

Complete blood count

(CBC) is useful as a general screening battery and helpful in the diagnosis of leukemia.

C-reactive protein

(CRP) is elevated in inflammatory conditions.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

(ESR) is often elevated in Ewing sarcoma, leukemia, lymphomas, eosinophilic granuloma, and infection.ESR values rise more slowly and elevations persist for longer durations than CRP values.

Alkaline phosphatase

(AP) values may be elevated in osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, lymphoma, and metastatic bone tumors. The value of the study is limited because of the natural elevation of this value during growth, especially in the adolescent.

Biopsy

A biopsy is a critical step in management and should be performed thoughtfully by an experienced surgeon. In most cases, an open biopsy is appropriate. Needle biopsy is indicated for lesions located at inaccessible sites and for special circumstances. The biopsy should provide an adequate sample of involved tissue, and the tissue should be cultured unless the lesion is clearly neoplastic. The biopsy procedure should not compromise subsequent reconstructive procedures.

Biopsies can be incisional, excisional, or compartmental in type. Excisional biopsy is appropriate for benign lesions such as osteoid osteoma or for other lesions when the diagnosis is known before the procedure and the lesion can be totally resected.

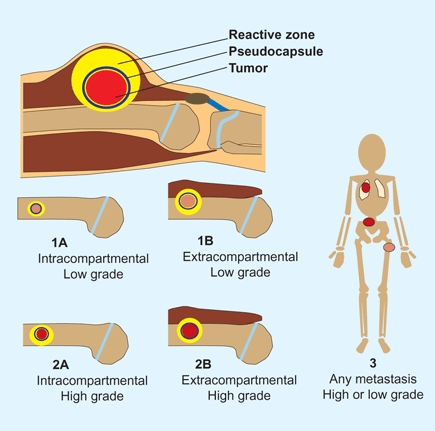

Staging

Staging of malignant tumors provides a means of establishing a prognosis. Prognosis depends on the grade of the lesion (potential for metastases), the extent and size of the lesion, and the response to chemotherapy. The extent of the lesion is categorized by whether the lesion is extracompartmental or intracompartmental [B] and whether any distant metastases are present. A knowledge of the response to chemotherapy helps the surgeon to determine the appropriateness of limb salvage procedures and how wide the surgical margins must be to avoid local recurrence following resection.

B Staging of musculoskeletal tumors Staging is determined by the grade and extent of the lesion. Intracompartmental lesions are those within a fascial compartment between deep fascia and bone; intraarticular lesions and those within bone. Based on Wolf and Enneking (1996).

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating myositis ossificans

Differentiating bone tumors from myositis ossificans (MO) is sometimes difficult. MO lesions have reactive bone that is most active on the margins. MRI studies are rarely necessary, but will show an inflammatory lesion with a tumor core.

Differentiating neoplasms, infection, and trauma

Sometimes a child presents with pain and tenderness over a long bone (usually the tibia or femur). The radiographs may be negative or show only slight periosteal elevation. The differential diagnosis often includes osteomyelitis, a stress fracture, or Ewing sarcoma. The evaluation usually requires a careful physical examination, radiographs, a bone scan, MRI, and a determination of the ESR and CRP.

Unicameral Bone Cysts

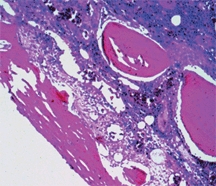

Simple, solitary, or unicameral bone cysts (UBCs) are common lesions of unknown cause that generally occur in the upper humerus or femur [A]. Theories of etiology include a defect in enchondral bone formation or altered hemodynamics with venous obstruction, causing increased interosseous pressure and cyst formation. The cysts are filled with yellow fluid and lined with a fibrous capsule [B].

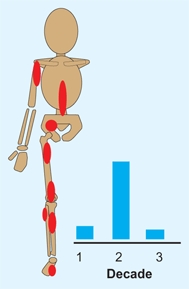

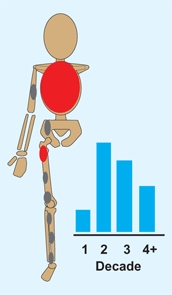

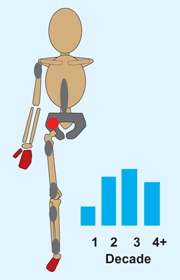

A Unicameral bone cysts Common locations (red) and age pattern of involvement (blue) are shown.

B Unicameral bone cyst lining This shows the synovial lining of a cyst wall.

Diagnosis

UBCs are most often first diagnosed when complicated by pain or a pathologic fracture [C]. Their radiographic appearance is usually characteristic. The lesions are usually metaphyseal, expand the bone, have well-defined margins, evoke little reaction, and appear cystic with irregular septa. Sometimes a fragment of cortical bone (called fallen leaf sign) can be seen in the bottom of the cavity.

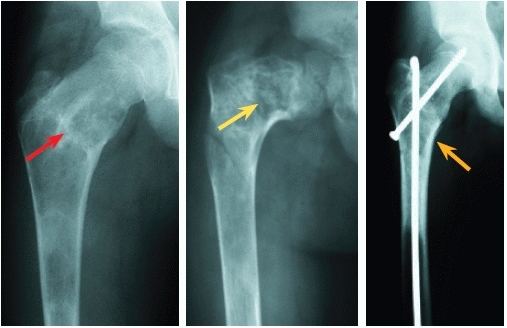

C Unicameral bone cysts in varied locations Note the typical active (red arrow) and inactive (yellow arrow) cysts with fractures. Flexible intramedullary rod fixation of an upper femoral cyst (orange arrow) is shown. A calcaneal cyst is an additional common site (white arrow).

Active cysts

abut the growth plate and occur in children less than 10 to 12 years of age. They are more likely to recur after treatment and are associated with growth arrest that may follow a fracture.

Inactive cysts

are separated from the plate by normal bone and usually occur in adolescents over 12 years of age.

Fractures

are usually the presenting complaint. Sometimes the fracture line is difficult to separate.

Management Principles

Management is complicated by recurrence. The usual natural history of these cysts is to become asymptomatic following skeletal maturation. The objective of treatment is to minimize the disability when cysts are likely to fracture. These lesions are not precancerous.

Humeral cysts

Place the child in a sling to allow the fracture to heal and to reestablish stability. Seldom does the effect of the trauma result in permanent healing of the cyst. Plan to manage the cyst by a series of injections [D] with steroid, bone marrow, or bone matrix. Some doctors recommend breaking up the adhesion by forceful injections or perforating the septa with a trochar. Recurrence can be managed by repeated injections or curettage and grafting with autogenous or bank bone. Opinions differ regarding how aggressively recurrence is managed.

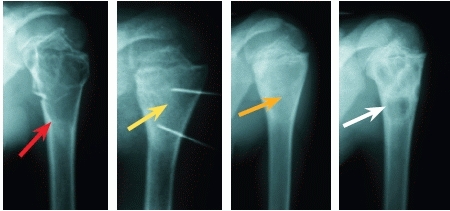

D Steroid injection treatment This is the classic location for a unicameral bone cyst. This 12-year-old boy developed pain in the right upper arm; a radiograph showed the typical cyst with a pathologic fracture (red arrow). The lesion was treated by steroid injection (yellow arrow) with satisfactory healing (orange arrow). A year later, the cyst recurred (white arrow), but not to a degree that required additional treatment.

Femoral cysts

are much more difficult to manage because of the load carried by the femur. Plan to curette and graft the cyst and stabilize the fracture with flexible intramedullary fixation. Complications include malunion with coxa vara and avascular necrosis with displaced neck fractures. This fixation is permanent and may prevent additional fractures even if some recurrent cyst formation occurs. An alternative approach is injection followed by spica cast protection for 6 weeks.

Calcaneal cysts

asymptomatic cysts may be managed by observation. Symptomatic or expanding cysts may do better by curettage and bone grafting. Small lesions may be treated by injection [E].

E Small calcaneal unicameral bone cyst This 14-year-old complained of pain and demonstrated a limp. X-rays demonstrated a small cystic lesion (red arrow). This was managed by perforating the cortex and septa with a trochar and injecting bone marrow (yellow arrow).

Aneurysmal Bone Cysts

An aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is considered to be a pseudotumor possibly secondary to subperiosteal or interosseous hemorrhage or a transitional lesion secondary to some primary bone tumor.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can usually be established by a combination of the location of the lesion, the age of the patient [A], and the appearance on conventional radiographs [B]. ABCs are eccentric, expansile, cystic lesions with a high recurrence rate. Lesions present in a variety of patterns and are sometimes difficult to differentiate from simple bone cysts [D].

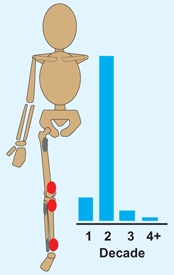

A Aneurysmal bone cysts Common locations (red) and age pattern of involvement (blue) are shown.

B Aneurysmal bone cyst of the vertebral column

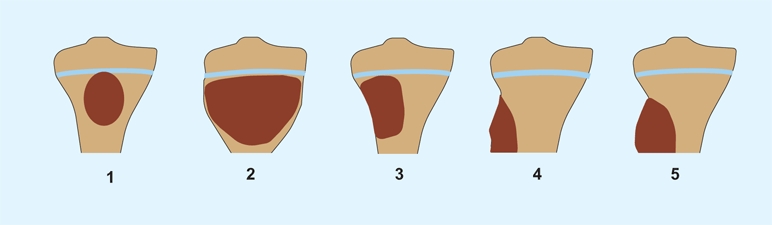

D Classification of aneurysmal bone cysts. Types 1–5 are various common patterns of lesions of long bones. Based on Capanna et al. (1985).

Activity of the lesion

The activity level can also be assessed by the appearance of the lesion’s margins.

Inactive cysts

have intact, well-defined margins.

Active cysts

have incomplete margins but the lesion is well defined.

Aggressive cysts

show little reactive bone formation and poorly defined margins.

Other imaging

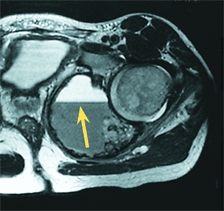

is often necessary, especially in aggressive cysts. Fluid levels are common and can be seen on CT scans and MRI studies [C].

C Aneurysmal bone cyst of the pelvis Note the extensive lesion (red arrow) and the fluid level (yellow arrow) on the MRI.

Management

Manage ABCs on the basis of the patient’s age, as well as the site and size of the lesion.

Spine

About 10–30% of ABC lesions are in the spine. They most commonly occur in the cervical and thoracic levels. Lesions arise in the posterior elements but may extend to involve the body. Study posterior elements with CT and MRI preoperatively. The possible need for a combined approach, complete excision, and stabilization, as well as the risk of recurrence, complicates management.

Long bones

Options include complete excision or saucerization, leaving a cortical segment intact, or curettage with cryotherapy or with a mechanical burr.

Pelvis

Manage most lesions by curettage and bone grafting. Some recommend selective embolization. Be prepared for extensive blood loss.

Complications

Bleeding can pose a significant problem.

Recurrence

may require more aggressive management that might include more extensive excision. Expect a recurrence rate of 20–30% following curettage. Recurrence is 10-60% higher in children under 10 years of age.

Fibrous Tumors

Fibrocortical Defects

Fibrocortical defects (or fibrous metaphyseal defects), fibrous lesions that are the most common bone tumor, occur in normal children, produce no symptoms, resolve spontaneously, and are found incidentally. They occur at the insertion of a tendon or ligament near the epiphyseal growth plate, which may be related to the etiology. They have a characteristic appearance that is eccentric and metaphyseal, with scalloped sclerotic margins. These lesions often cause concern that sometimes leads to inappropriate treatment. Fortunately, the lesions have a characteristic radiographic appearance that is usually diagnostic. They are small, cortical in location, and well-delineated by sclerotic margins. They usually resolve spontaneously over a period of 1 to 2 years.

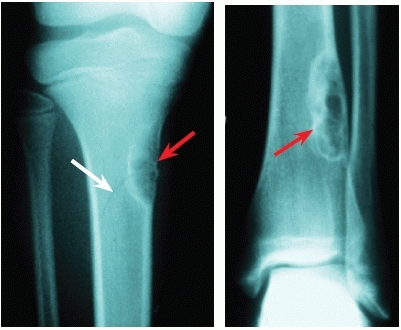

Nonossifying Fibroma

A larger version of the fibrocortical defect is called a nonossifying fibroma. These lesions are present in classic locations and are usually diagnosed during adolescence [A]. They are metaphyseal, eccentric with scalloped sclerotic margins [B and C], and may fracture when large or if present in certain locations. Manage most by cast immobilization. Resolution of the lesion occurs with time. Rarely, curettage and bone grafting are indicated if the lesion is unusually large or if a fracture through the lesion occurs with minimal trauma.

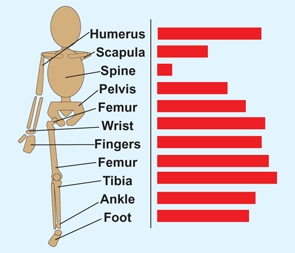

A Nonossifying fibroma Common (red) and less common (gray) locations are shown. Age pattern of involvement is shown in blue.

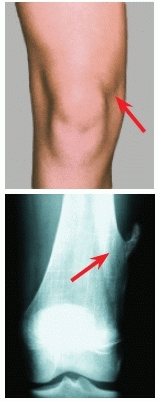

B Nonossifying fibroma of the distal femur

C Typical nonossifying fibroma These are typical features and locations (red arrows). Note the fracture line (white arrow) through the proximal tibia, with its origin in the fibroma.

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia includes a spectrum of disorders characterized by a common bony lesion. The neoplastic fibrosis replaces and weakens bone, causing fractures and often a progressive deformity. Ribs and the proximal femur are common sites, and the lesions are most common in adolescents [D].

D Fibrous dysplasia Common (red) and less common (gray) locations are shown. Age pattern of involvement is shown in blue.

Fibrous dysplasia can be monostotic or polystotic. The polystotic form is more severe and is more likely to cause deformity. This deformity is often most pronounced in the femur, where a “shepherd’s crook” deformity is sometimes seen [E], and may show extensive involvement of the femoral diaphysis. Rarely, fibrous dysplasia is associated with café-au-lait skin lesions and precocious puberty, as described with Albright syndrome.

E Fibrous dysplasia of proximal femur These patients show a femur at risk for deformity (red arrow), varus deformity (yellow arrow), and intramedullary fixation to prevent deformity (orange arrow).

Medical management using drugs that inhibit osteoclastic activity have not been widely used in children but offer an alternative to surgical management.

Surgical management of fibrous dysplasia involves strengthening weakened bone using flexible intramedullary rods. Leave these rods in place indefinitely to prevent fractures and progressive deformity [E].

Benign Cartilagenous Tumors

Osteochondroma

Osteochondromas (osteocartilagenous exostoses) include solitary [A] and multiple [B] lesions. The multiple form is inherited but thought to be due to a loss or mutation of two tumor suppressor EXT 1 and 2 genes. Lesions sometimes develop after chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Most tumors develop by enchondral ossification under a cartilage cap.

A Common locations of solitary osteochondromas

B Multiple familial osteochondromas Note the widespread involvement. Based on data by Jesus-Garcia (1996).

Diagnosis

Osteochondromas are usually first noted as masses that are painful when injured during play [C]. These lesions are usually pedunculated but may be sessile. They may grow to a large size. Osteochondromas are so characteristic in appearance that the diagnosis is made by conventional radiographs.

C Typical location for symptomatic lesions Lesions about the knee are frequently irritated and painful (red arrows).

Solitary osteochondromas

These lesions are most common in the metaphyses of long bones. They occur sporadically and present as a mass, often about the knee. Presentations in the spine may be associated with neurologic dysfunction.

Multiple osteochondromas

The common multiple form [D] is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and is more common in boys. Multiple lesions about the wrist and ankle often cause progressive deformity [E]. Others may cause valgus deformities about the knee.

D Multiple osteochondromas This child has multiple lesions (arrows).

E Common deformities that cause disturbed growth These are common about the wrist (red arrow) and ankle (yellow arrow).

Management

depends on the location and size of the tumor.

Pain

is the most common indication for removal [G]. Often several lesions are removed in one operative setting. Complications of excision include peroneal neuropraxia, arterial lacerations, compartment syndromes, and pathologic fracture.

G Removed osteochondroma This resected lesion is large and irregular.

Valgus knee

can be managed by medial femoral or tibial hemistapling [F] in late childhood.

F Deformity correction Correction of knee and ankle valgus by placement of staples and medial malleolus screws.

Limb length inequality

may require correction by an epiphysiodesis.

Wrist deformities

result from growth retardation and bowing of the distal ulna. Management of these deformities is complex and controversial. Studies in adults show surprisingly little pain and functional disability, considering the magnitude of the deformity and the unsightly appearance.

Ankle deformities

result from growth retardation of the distal fibula, producing ankle valgus. Studies in adults show significant disability and suggest that prevention or correction of tibiotalar valgus should be undertaken in late childhood or adolescence. Consider resecting the osteochondroma and performing an opening wedge osteotomy of the distal tibia to correct the valgus. When identified in childhood, consider placing a medial malleolar screw [F] to prevent excessive deformity. Deformities are often complex, and operative correction must be individualized.

Prognosis

Very rarely, malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma occurs during adult life. This transformation is most common in solitary lesions, usually from lesions involving flat bones, and occurs about two decades earlier than primary chondrosarcomas. Most tumors are low grade. Because the transformation is very rare, prophylactic removal of exostoses is not appropriate.

Enchondroma

These cartilage tumors are located within bone. They are common in the phalanges and long bones and increase in frequency during childhood [A]. They produce the classic characteristic of cartilage tumors of speckled calcification within the lesion [B].

A Enchondromas Common (red) and less common (gray) locations are shown. Age pattern of involvement is shown in blue.

B Ollier disease Note the extensive lesions of the distal femur and tibia (red arrows) with shortening and varus deformity.

Types

There are several different types of enchondromas.

Solitary lesions

occur most commonly in the hands [C] and feet. Removal and grafting is indicated if the lesions cause disability.

C Multiple enchondromas Note the extensive involvement of several fingers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree