Unicameral Bone Cyst

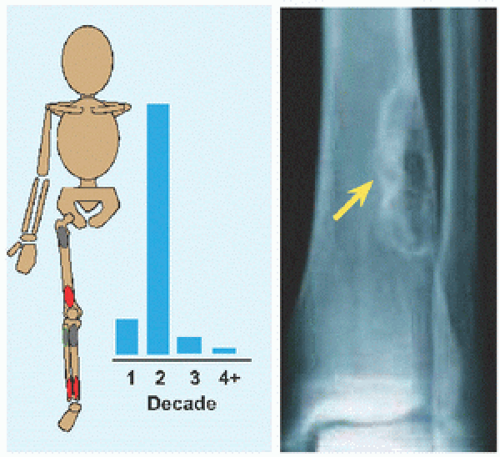

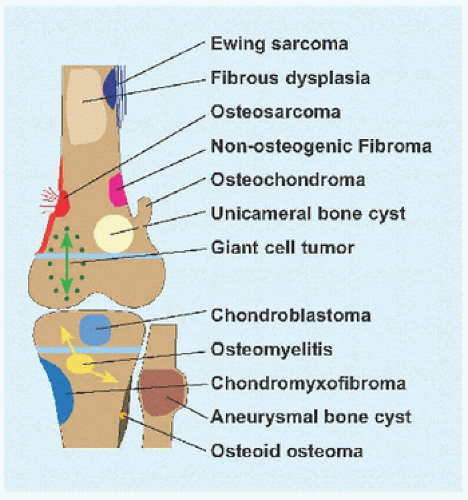

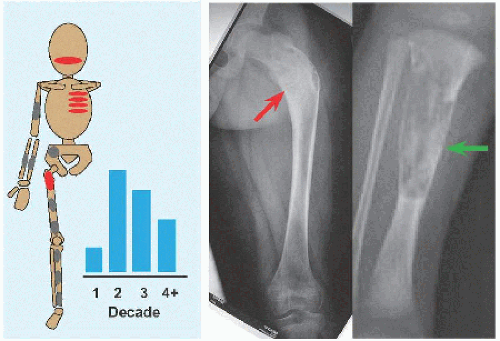

The name implies a “single chamber” (Latin camera = Greek καµαρα: “vaulted chamber”) without loculation, although some have septæ. This most commonly occurs in the humerus and femur. Cause is unknown. The cysts are filled with yellow fluid and lined with a fibrous capsule.

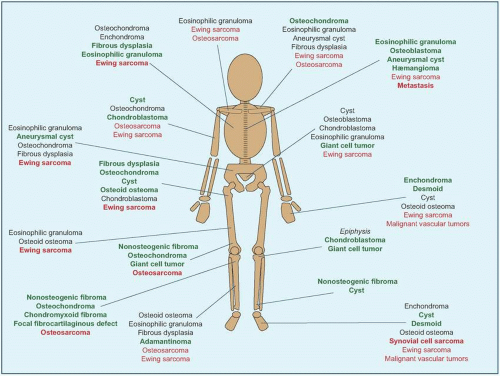

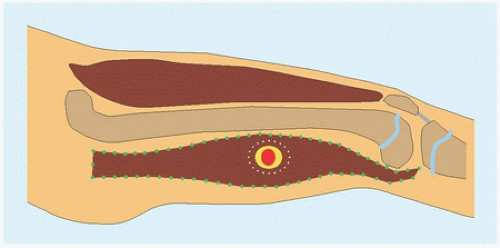

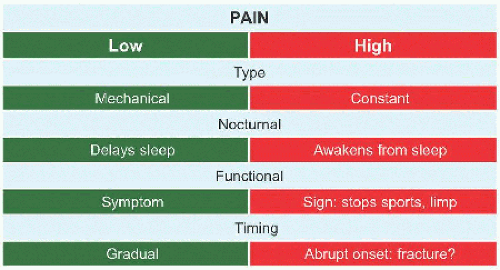

Evaluation These may be incidental or may present with pain. They are metaphysial and travel toward the diaphysis with growth. Incidental findings are assessed for fracture risk [A]. Pain indicates bending under load or fracture and may be severe enough to interfere with function. Lesions in the proximal femur are high risk because of concentration of the force of weight bearing and the grave anatomic consequences of fracture in this region.

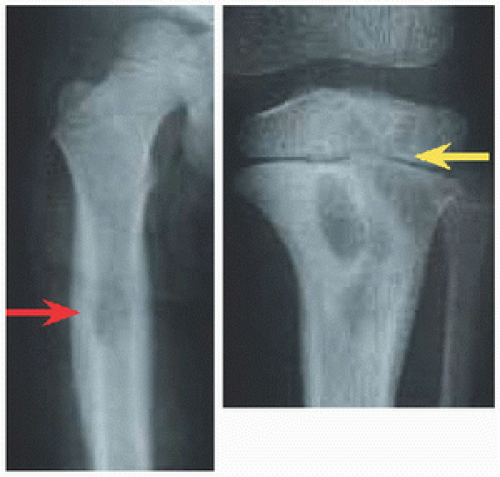

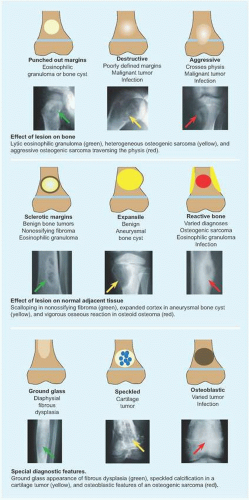

RÖNTGENOGRAMME The lesion is central, nonexpansile, geographic with a sclerotic margin, and lytic. It may have septæ and an osseous fragment may float in its midst, known as “fallen leaf sign.”

Management The natural history is spontaneous resolution of cysts by maturity in most cases. Latent cysts may be observed. Active cysts, which abut the physis, grow inexorably, and may fracture, tend to be treated surgically. Age, location, and fracture risk and consequences guide treatment.

LOW RISK EXCEPT FEMUR Observe. A humeral cyst that is small, asymptomatic, or acceptably painful may be managed conservatively, such as activity modification and nonnarcotic analgesics, and may resolve with maturity.

LOW RISK PROXIMAL FEMUR Observe or treat surgically because of concerns regarding load at, and fracture of, the hip.

HIGH RISK Observe if patient is very young and humerus is involved, or treat surgically. The proximal femur trumps age: consider fixation even in the very young.

FRACTURE EXCEPT FEMUR Treat by closed methods as long as alignment is acceptable. Healing of the fracture may partially heal cyst, potentially converting a cyst that is high risk by size into one that is low risk due to filling in with new bone.

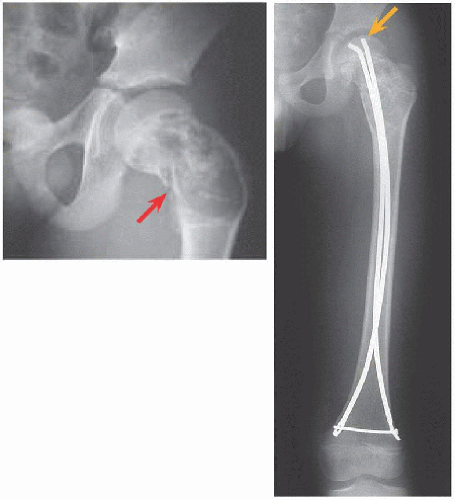

FRACTURE FEMUR Treat surgically. Immobilization, for example, in hip spica cast, is associated with residual deformity, in particular coxa vara, due to intrinsic instability of the fracture and incomplete healing. For the proximal femur, improved alignment with surgical fixation may reduce complications of fracture such as malunion and osteonecrosis.

Surgical treatment may be divided into cases.

PERCUTANEOUS WITHOUT FIXATION This began as injection of steroid (Scaglietti), for its angiostatic and fibroblastic inhibitory effects. The method has evolved in multiple directions such that there is no consensus on best practice. It is preferred for the upper limb and lower risk lower limb lesions.

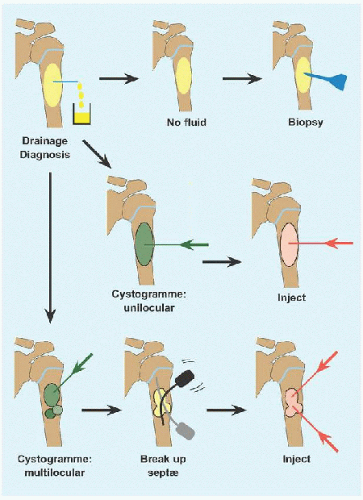

The cyst is drained. If it is solid, reconsider diagnosis and perform an incisional biopsy.

A cystogramme determines whether the cyst is uni- or multilocular. If the former, inject with steroid or other adjuvant. Bone marrow aspirate may bring mesenchymal stem cells that will promote bone ingrowth and healing. Calcitonin inhibits osteoclasts. Calcium sulfate cement is osteoconductive. Proprietary fibrosing agents have been promoted.

If the latter, break up septæ to form a unilocular cyst. In the process, perforate the cyst to create channels of communication with the medulla, based upon the rationale that altered hæmodynamics with venous obstruction may be a causative factor, and to allow access to the cyst by bone stem cells.

Repeat for recurrence.

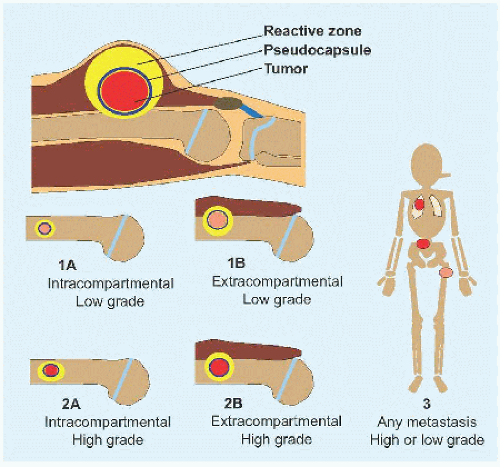

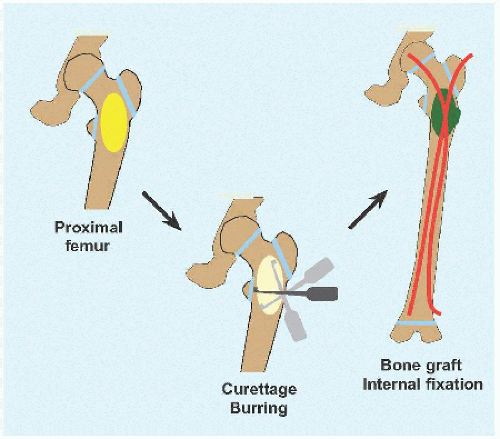

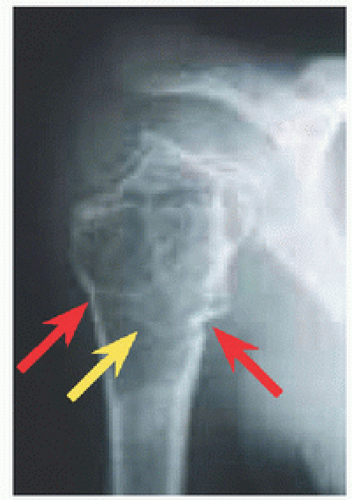

OPEN WITH FIXATION This is indicated for high-risk lesions, such as proximal femur [D], or where open access is simple, for example, calcaneus.

Create an ovoid window to avoid stress concentration at an angle. The cyst may dictate location of this at the eroded cortex.

Débride the wall to remove all cells, manually or with power.

Consider adjuvant intralesional therapy to kill residual cells, for example, liquid nitrogen (freezing), phenol (chemical), argon laser (coagulation), or hydrogen peroxide. For liquid nitrogen, leave in cavity until it evaporates; for other chemicals, let sit for 2 to 3 minutes. Cycle thrice. Reduce application hazard by controlling the agent within the osseous cavity in order to minimize injury to surrounding soft tissue. These augment but do not substitute for complete débridement.

Pack the cyst with graft, allogenous or autogenous, or with a substitute. There are no robust data suggesting anything is better than bone, and allogenous bone avoids the morbidity of harvesting bone, in particular because much may be needed to fully fill a large cyst.

If the bone is stable, apply a cast. If internal fixation is indicated, for example, proximal femur, medullary implants will load share and thereby be more durable in the event of recurrence. In the immature child, elastic medullary nails may be inserted antegradely or retrogradely. They provide stability even in proximal lesions because they may be anchored in the unaffected and hard proximal epiphysis: no physial arrest will occur given their smooth surface and small fractional cross-sectional area [E].

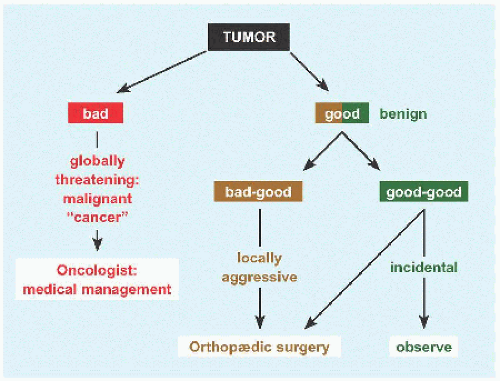

Complications While bone cyst is a benign or “good” tumor, it is a “bad-good” tumor because outcomes can be vexing.

Recurrence. Some factors cannot be controlled, such as abutment against a physis. The principal factor that is controllable is débridement; hence the recommendation to use a burr, to be methodical, to proceed until healthy bleeding bone, and to leave only periosteum in places (so long as the bone is not unreasonably destabilized or resected).

Growth disturbance. This may be iatrogenic or related to activity of cyst. The former may be minimized by avoiding physis during operation. The latter is a reflection of duration and aggressiveness of cyst.

Malunion. This is most common in the proximal femur. Likelihood increases with closed management.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

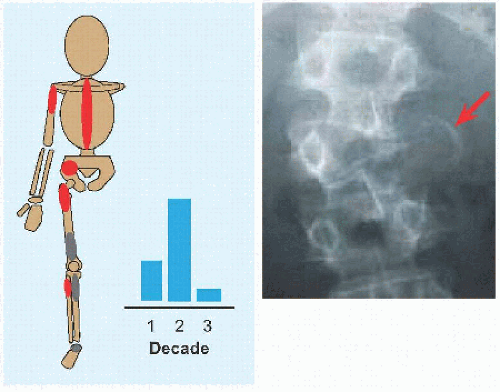

As the name implies, this is vascular and expansile. Cause is unknown, although vascular malformation is most subject to speculation. Evaluation and management principles overlap with unicameral cyst, with key distinctions. Aneurysmal cyst is more aggressive:

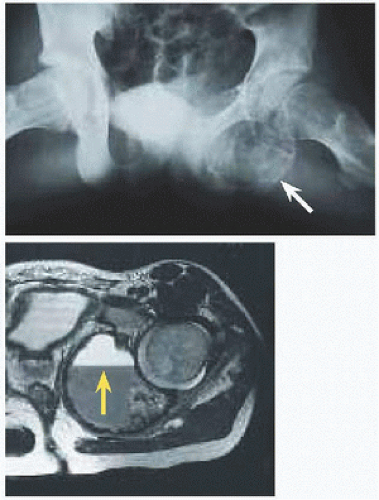

Location. 1/4 arise in the axial skeleton, including posterior elements of the spine and the periacetabular region of the pelvis [F]. Consequences are greater morbidity of disease, for example, neural compromise, and of treatment, including more invasive dissection and more complex reconstruction.

Recurrence. Correct surgical technique has reduced a formerly universal rate. Recurrence occurs within 2 years of operation, although children must be followed until maturity.

Association with other tumors, including giant cell and osteosarcoma, in which it may represent the cystic component of a primary tumor.

Evaluation On röntgenogramme, it is eccentrically expansile, lytic, and multiloculated, giving a “soap-bubble” appearance. The thin margin has been likened to an “eggshell.” The radiographic appearance may raise concern and prompt further imaging. Scintigramme may show a “halo” of increased uptake surrounding a central cold region. MRI will show blood-fluid levels [G] and define soft tissue extension.

Management This tends to be open and has the additional considerations:

Preoperative angiography and selective embolization before surgical treatment of large lesions, in particular in the pelvis, will decrease hæmorrhage and may shrink the lesion to decrease recurrence where complete resection is unrealistic.

Entry into a cyst will return blood. Include soft tissue within, or the lining of, the cyst for biopsy, which will show proliferative fibroblasts, spindle cells, osteoid, and multinucleated giant cells.

Break up all septæ to define the entire cyst wall, which may be interrupted.

Consider an en bloc resection with reconstruction where feasible to reduce recurrence.

In the spine, excision may result in instability necessitating reconstruction, including bone grafting, fusion, and internal fixation.