Fig. 19.1

Levels of foot amputation. Digital amputation (green line), transmetatarsal amputation (orange line), Lisfranc (tarsometatarsal) amputation (red line), and Chopart’s amputation (blue line)

Careful attention to surgical principles specifically designed to optimize healing, preserve foot function, and avoid recurrent wound breakdown is the focus of our TMA and Lisfranc amputation protocols, which are presented in this chapter. The traditional TMA surgical procedure and incision plan continues to be the desired approach for patients with neuropathic forefoot ulcers associated with metatarsal osteomyelitis and for gangrene that is isolated to the digits that is not amenable to isolated ray procedures. Incorporation of advanced podiatric, plastic, and vascular surgical approaches allows success with TMA and Lisfranc amputation for more proximal wounds and infection that would otherwise require leg amputation.

Transmetatarsal Amputation

The obvious biomechanical consequence associated with a TMA is shortening of the lever arm of the foot which impacts balance, gait, and posterior muscle group function. Care is taken to recreate a natural metatarsal parabola while attempting to preserve a functional metatarsal length when possible. Many patients undergoing TMA have pathologic mechanics due to prior surgery, digital deformity, degenerative arthritis, or neuropathic fracture which is often the reason for recurrent wounds and persistent infection. The TMA procedure is intended to improve the mechanics of this pathologic foot type which goes against the commonly held belief that partial foot amputation makes the foot more prone to problems. The ideal zone of resection is at the metatarsal neck just proximal to the metaphyseal flare. Leaving the distal metaphyseal flare predisposes the foot to recurrent tissue breakdown, since the flare is pronounced on the plantar aspect. This diaphyseal level of resection is also preferred since metaphyseal bone resection may encourage heterotopic ossification (HO) (Fig. 19.2) as described in Chap. 17 [8]. Excessive metatarsal shortening should be avoided although the extent and location of open wounds or gangrene ultimately dictate location of metatarsal resection in an effort to transect the metatarsals short enough to achieve soft tissue coverage. Rotational flaps are beneficial in this regard, which are incorporated to provide soft tissue coverage without excessive bone resection. The anticipated extent of osteomyelitis based on preoperative imaging and direct surgical inspection also influences the ideal level of bone resection. A TMA is not expected to produce a clean bone margin in cases of metatarsal osteomyelitis. A metatarsal preservation approach is preferred which combines selective bone debridement with medical treatment of residual osteomyelitis in an effort to maintain optimal postoperative foot function. Advanced surgical techniques including medullary reaming, staged resection, and insertion of antibiotic cement also supports achievement of a clinical cure of metatarsal osteomyelitis without excessive surgical resection.

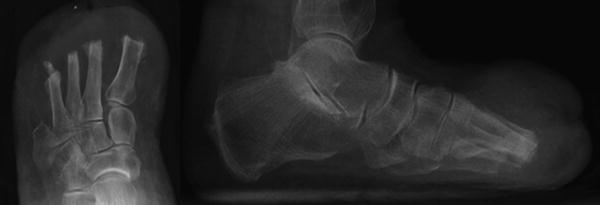

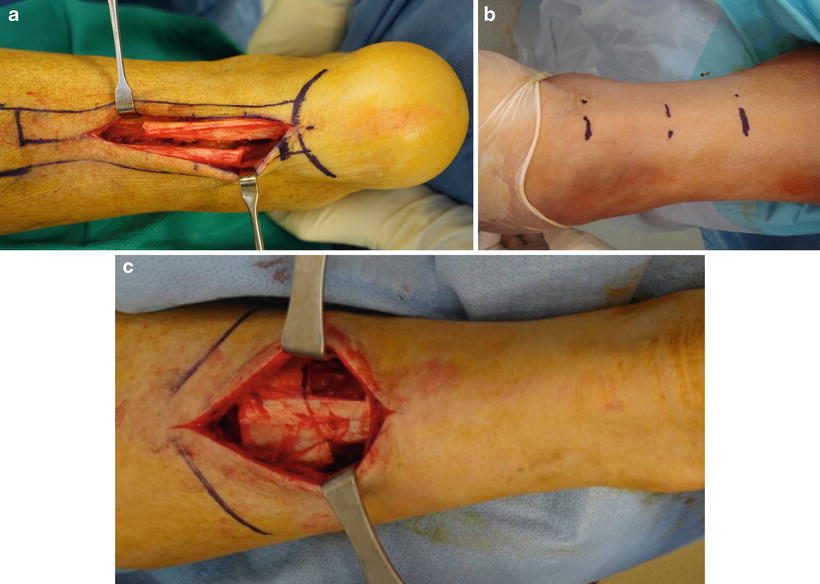

Fig. 19.2

Heterotopic ossification (HO) following transmetatarsal amputation (TMA). AP and lateral radiographs with noted HO formation to the distal metatarsal amputation stumps following TMA increase the risk of recurrent forefoot ulceration. Note massive swelling of the forefoot on the lateral view which is commonly seen with heterotopic bone formation

The outlook for gangrene-related TMA is not as optimistic when compared to osteomyelitis associated with neuropathic ulceration, due to compromised healing potential associated with vascular disease. There is less concern for osteomyelitis with gangrene although dead tissue frequently becomes infected while waiting for demarcation of gangrene. There is a fine line between allowing forefoot gangrene to demarcate and letting dry gangrene turn into infected wet gangrene. A close “wait and watch” approach is reasonable, yet waiting too long is counterproductive as vascular compromise and infection are a dangerous combination. Vascular intervention is common during this waiting period which is ideally performed prior to TMA. Antibiotics are only needed if infection is suspected or confirmed. Once healed, the gangrene-related TMA stump tends to remain durable without the tendency for recurrent ulceration unless there is concomitant peripheral neuropathy or residual deformity.

Posterior muscle group contracture or ankle equinus is a common cause of recurrent ulceration after TMA. Moore and Jolly noted that the gastrocnemius and soleus have little opposition once the extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus have been eliminated and only the tibialis anterior remains to provide dorsiflexion [9]. Many patients with neuropathic ulcers leading to TMA have preexisting equinus, which will need to be addressed if TMA is to be successful. Tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL) or gastrocnemius recession may be performed concomitantly or after complete healing of the TMA site depending on the clinical situation (Fig. 19.3). There is risk of cross-contamination from the infected or contaminated amputation site when clean and dirty procedures are performed in the same setting; however, this is rare due to the effectiveness of isolating the surgical sites. The authors’ preference is to delay the Achilles lengthening procedure to see if it is necessary once the patient is ambulatory. One benefit of delayed posterior lengthening is the ability to rehabilitate and ambulate during the initial 6 weeks of tendon healing without risk of harm to the healing amputation site. Trying to maintain ankle dorsiflexion after concomitant TMA and TAL procedures is difficult as posterior splints can cause pressure sores on the posterior heel or plantar foot. Profound equinus contracture after TMA is more common when open guillotine TMA procedures are left to heal secondarily over the course of many months. Prolonged non-weight bearing with this approach almost assures equinus contracture. Primary closure and flap coverage of the amputation site allows prompt healing and timely return to full ambulation at about 6 weeks postoperative which is the best method to avoid equinus contracture.

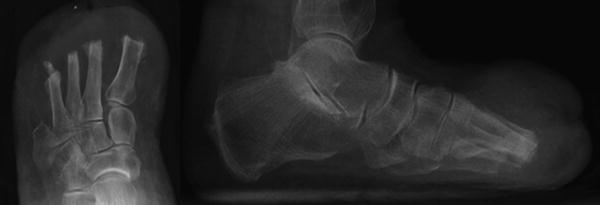

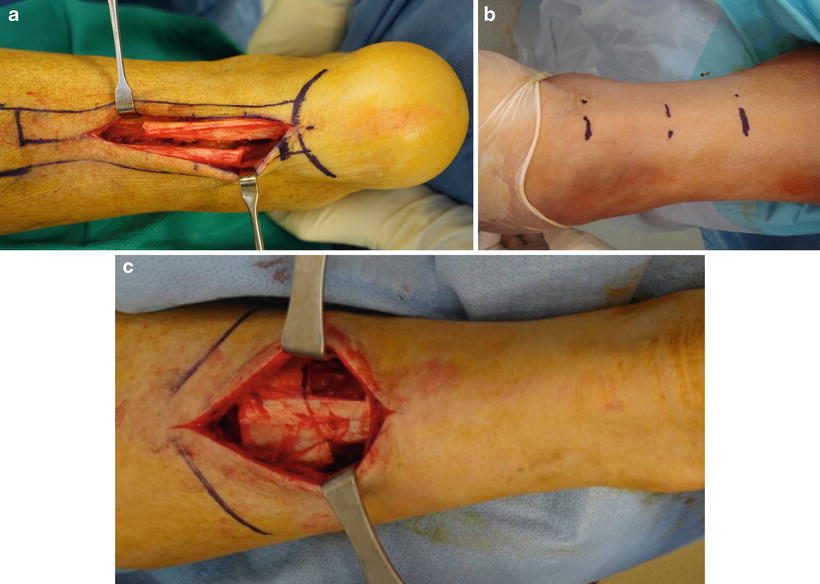

Fig. 19.3

Posterior muscle group lengthening for ankle equinus. (a) Open tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL) is the most effective and controlled method to address gastroc-soleal equinus deformity. Note aggressive open lengthening which allows direct suture repair to avoid over lengthening or retraction while healing. (b) Percutaneous triple hemi-section TAL is desired when the soft tissue is not as amenable to open procedures. The percutaneous technique does not allow suture repair of the lengthened tendon which may result in overcorrection of the equinus deformity but has less risk of wound healing problems and is more conducive to surgery in the supine position. (c) Open gastrocnemius recession is indicated for patients with equinus deformity isolated to the gastrocnemius. Skin healing is generally improved at the mid-calf level although chronic edema may compromise healing of calf incisions

Standard Transmetatarsal Amputation Procedure

The TMA procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia although intravenous sedation with an ankle block is also possible, especially in patients with neuropathy. An ankle tourniquet may be used to minimize blood loss in patients with neuropathic ulcers who frequently have robust vascular supply. The procedure is performed wet in patients with compromised circulation to ensure that viable tissue margins are achieved. The tourniquet is released prior to closure to ensure hemostasis and to assess vascularity at the level of resection. An atraumatic surgical technique is critical including use of skin hooks to manipulate the dorsal and plantar flaps. Skin incisions are made directly to bone with no attempt to undermine the tissue planes looking for blood vessels or nerves. The metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) capsules, sesamoids, and plantar plates are removed in an effort to minimize the chance of HO formation and to decrease the bulk of the plantar flap. The plantar flap is otherwise maintained at full thickness to maximize vascularity and protect against forces of weight bearing. Periosteal elevation at the metatarsal neck is limited to the area of bone resection which also minimizes the likelihood of HO formation. Larger bleeding vessels are tied and use of electrocautery is selective in an effort to preserve tissue viability.

The traditional TMA approach utilizes a transverse fish mouth-type incision creating dorsal and plantar flaps (Figs. 19.4 and 19.5). The plantar flap is typically longer and thicker than the dorsal flap which creates unmatched flaps at the time of closure. The dorsal incision is made just behind the sulcus of the toes which is 1–2 cm distal to the location of metatarsal bone resection. The plantar incision is made more distally to ensure coverage. The incisions are altered accordingly if the local tissue is compromised by poor circulation, gangrene, or neuropathic ulceration. The medial and lateral apices of the incision are placed at the midway point from dorsal to plantar and midway along the first and fifth metatarsal shafts, respectively. The initial incision is made perpendicular to the skin surface using a #10 blade. A 90° plunge-cut technique is used with the entire incision made directly down to bone in an effort to maintain full-thickness flaps and to avoid beveling of the incision (Fig. 19.6). The dorsal flap is not actually raised, but rather retracted proximally to gain access to the metatarsal necks. The periosteum is then cut medially, laterally, and dorsally over the neck of each individual metatarsal. A metatarsal elevator is then used to minimally elevate the periosteum to allow access for metatarsal resection using a bone saw (Fig. 19.7). This ensures that the distal perforating inter-metatarsal vessels remain intact while avoiding excessive inter-metatarsal dissection. The periosteum distal to the metatarsal neck is left attached to the metatarsal head to be removed with the forefoot in an effort to minimize the risk of HO formation.

The metatarsals are transected proximal to the metaphyseal flare with a power bone saw while maintaining the innate metatarsal parabola (Fig. 19.7). The first and second metatarsals are cut at approximately the same length while the remaining metatarsals taper gently in the lateral direction. The metatarsals should be cut with a longer dorsal shelf compared to the plantar edge to avoid plantar prominence. The first and fifth metatarsals should be beveled more medially and laterally, respectively, to avoid problems with shoe pressure. Penetrating towel clamps are then placed medially and laterally through the digits to allow manipulation with a no-touch technique while raising the plantar flap. The toes and metatarsal heads are detached as one unit from the plantar flap (Fig. 19.8). The first metatarsal sesamoid apparatus and lesser metatarsal phalangeal joint plantar plates are then carefully dissected and removed from the plantar flap to decrease bulk and expose the underlying vascular tissue that will contribute to healing. This method seems to provide maximum flap viability with the least amount of operative trauma.

It is imperative to ensure that no bony prominences remain on the metatarsal stumps as this increases the propensity for future wound breakdown. Bone-cutting or bone-crushing forceps are avoided in favor of a power bone saw to minimize splintering which promotes HO formation and irregular bone surfaces [8]. Direct palpation of the metatarsal stumps and intraoperative imaging confirms the desired result. Thorough irrigation is used to wash away any bone debris. Bone is then procured for pathologic biopsy and culture. The optimal location of biopsy specimen is based on the location of the open wound and findings of preoperative imaging (Fig. 19.9). A clean margin biopsy can be sent for evaluation of residual osteomyelitis, especially in digital osteomyelitis. Margin biopsy frequently involves curettage of an exposed medullary canal in order to preserve length of the metatarsal shaft, or a section of bone can be procured when remodeling the metatarsal stumps to achieve the proper metatarsal parabola. Biopsy from the discarded phalanges is taken on the back table after wound closure to minimize the chance of cross-contamination if the pathology and cultures are not obtained directly from the surgical site. A metatarsal head specimen is also common, depending on location of preoperative wounds and suspected location of osteomyelitis.

Note that electrocautery has not been used up to this point in the operation. The tourniquet is released if being used. Larger bleeding vessels are tied with absorbable suture ties during dissection or prior to closure. The cautery is then used sparingly for selective hemostasis. A closed suction drain may be used depending on circulation, residual bleeding, perioperative anticoagulation status, and anticipated dead space.

Interrupted skin sutures are used to close the wound as deep sutures are not typically needed or desired (Fig. 19.10). A no-touch suture technique is used to allow minimal handling of the dorsal and plantar flaps. Hash marks are helpful to preplan flap approximation with the expectation that slight puckering will occur due to the plantar flap being longer and broader than the dorsal flap. A surgical case is detailed in Figs. 19.4, 19.5, 19.6, 19.7, 19.8, 19.9, 19.10, and 19.11.

Fig. 19.4

Patient selection criteria for standard transmetatarsal amputation technique. Case demonstrating recurrent first ray ulcer complicated by extensive osteomyelitis and prior fifth ray amputation. A large plantar medial neuropathic wound with bone exposure and first metatarsal phalangeal osteomyelitis was treated with transmetatarsal amputation (TMA). The traditional TMA incision design requires viable dorsal and plantar tissue flaps. The medial wound location seen here allowed excision with the traditional TMA approach, while plantar wounds and extensive forefoot gangrene may necessitate either a shorter level of amputation or advanced plastic surgical techniques including rotational flaps

Fig. 19.5

Traditional transmetatarsal amputution (TMA) incision design. Dorsal and plantar TMA flaps were drawn with the medial and lateral apices about midpoint from dorsal to plantar and midway along the first and fifth metatarsals, respectively. This patient required a slightly shorter than typical TMA due to prior fifth ray amputation and first ray osteomyelitis. Wound location also impacts the level of bone resection

Fig. 19.6

Transmetatarsal amputation incision technique. The incision technique for midfoot amputation involves dorsal and plantar incisions made directly to bone with cuts made at 90° to the skin surface. No attempt is made to undermine the tissues searching for bleeding vessels during the initial incision as this may compromise viability of the flap

Fig. 19.7

Traditional transmetatarsal amputation with metatarsal resection performed to recreate a normal metatarsal parabola utilizing a bone saw. Irrigation was used to cool the saw and wash away bone dust in an effort to minimize risk of heterotopic bone formation. Note that minimal periosteal elevation or raising of the dorsal flap was performed for this same reason. Intraoperative imaging was used to confirm the desired level of metatarsal resection and recreation of a functional metatarsal parabola

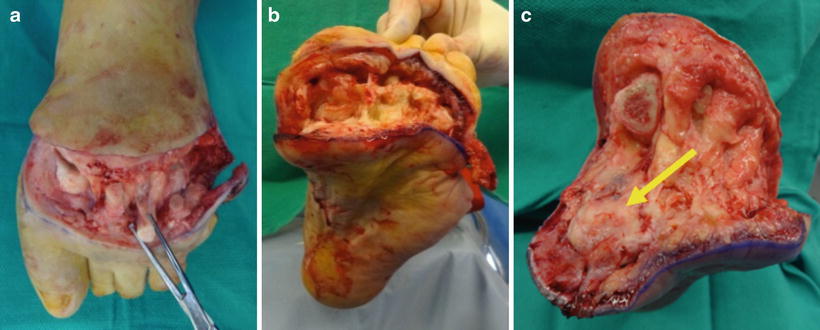

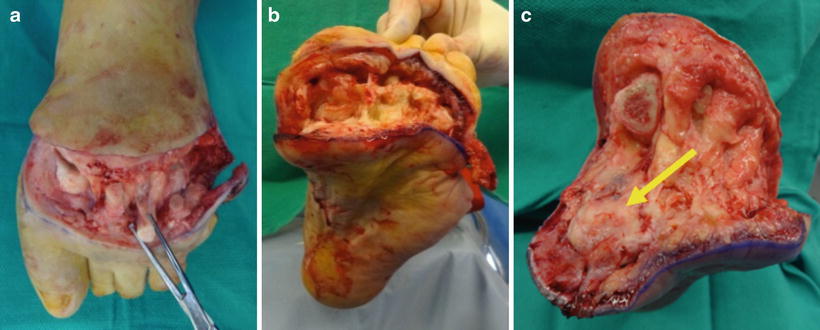

Fig. 19.8

Disarticulation of forefoot in TMA. The forefoot is disarticulated while maintaining full thickness of the plantar flap. The first ray sesamoids (yellow arrow) and lesser metatarsophalangeal joint plantar plates remain within the plantar flap upon disarticulation of the forefoot. These structures were then carefully dissected and removed which helps to preserve a full-thickness and well-vascularized plantar flap

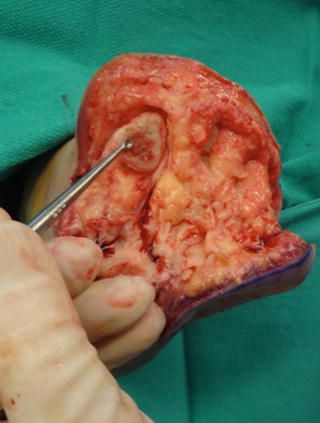

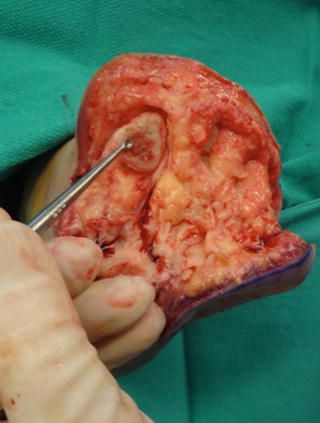

Fig. 19.9

A curette was used to procure a proximal margin biopsy from within the first metatarsal medullary canal following TMA. Direct visualization of the cortical and medullary bone provides important information regarding extent of infection and should be discussed in the operative report when relevant

Fig. 19.10

Simple sutures were used to close the transmetatarsal amputation flaps

Fig. 19.11

Standard TMA postoperative radiographs. Postoperative imaging confirmed recreation of the desired metatarsal parabola. An immediate postoperative image is shown. (a) A gentle taper on the medial and lateral sides minimizes the likelihood of recurrent breakdown of the amputation site. (b) Lateral imaging confirmed tapered metatarsal resection to minimize the risk of plantar prominence

Lisfranc (Tarsometatarsal) Amputation

Compared to TMA, Lisfranc amputation is a less desirable level of amputation with regard to weight bearing function, resistance to recurrent wounds, and longevity of the stump (Fig. 19.12) [3, 4]. Lisfranc amputation is generally indicated for midfoot wounds with associated osteomyelitis in the proximal metatarsals, extensive forefoot gangrene, frostbite, and mangling injuries of the forefoot (Fig. 19.13). Extensive heterotopic ossification (HO) from prior metatarsal resection may also warrant Lisfranc disarticulation in an attempt to limit HO formation after revision surgery which is discussed in Chap. 17. Caution should be taken before proceeding with this procedure because the native biomechanics of the foot are greatly altered which may need to be addressed at the time of surgery. Disarticulation of the first metatarsal from the medial cuneiform joint may result in complete loss of tibialis anterior (TA) and peroneus longus (PL) tendon insertions depending on the need to remodel the plantar aspect of the medial cuneiform. Disarticulation of the fifth metatarsal from the cuboid results in complete loss of the peroneus brevis (PB) tendon insertion. Loss of TA function leads to foot drop and equinus contracture, while loss of PL and PB function leads to unopposed inversion through the tibialis posterior tendon. An attempt should be made to preserve or transfer these tendons at the time of amputation when possible.

Fig. 19.12

Indications for Lisfranc amputation. (a) Forefoot gangrene with secondary infection, (b) extensive tissue necrosis from frostbite, and (c) midfoot ulceration with underlying osteomyelitis

Fig. 19.13

Posterior tibial (PT) tendon open Z-lengthening. Tendon balancing beyond TAL is common with Lisfranc amputation more so than TMA. Open Z-lengthening of the PT tendon is shown with incision made from the tip of the medial malleolus toward the navicular tuberosity. The arrow indicates the divergence of the tibial nerve and posterior tibialis artery from the posterior tibialis tendon making this incision location safe

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree