Chapter 3

Transfers and bed mobility of people with lower limb paralysis

The key mobility tasks are sitting unsupported, rolling, moving from lying to sitting and transferring. The most common way of performing each task is described in terms of sub-tasks. Sub-tasks can be thought of as critical steps. The text is supplemented by video clips freely available at www.physiotherapyexercises.com.

Sitting unsupported

Sitting unsupported is important because it is an integral part of transferring and dressing.1–4 It is also used when reaching and grasping for objects while sitting on the front edge of a commode, toilet or wheelchair.5 For example, reaching for something in a high cupboard requires moving to the front edge of the wheelchair and reaching upwards and laterally.

One strategy is to use upper limb muscles to help stabilize the trunk in an upright position.1,5,6 The muscles capable of providing trunk stability are the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis and serratus anterior muscles. All these muscles have insertions on the trunk or scapula, and while not normally considered postural muscles, they can take on this role in patients with trunk paralysis. Their importance helps explain why patients with C6 tetraplegia attain a higher level of independence than those with C5 tetraplegia (see Chapter 2). Patients with C6 tetraplegia have reasonable strength in these shoulder muscles but patients with C5 tetraplegia do not. Consequently, patients with C5 tetraplegia have great difficulty sitting unsupported and cannot normally perform associated mobility tasks.

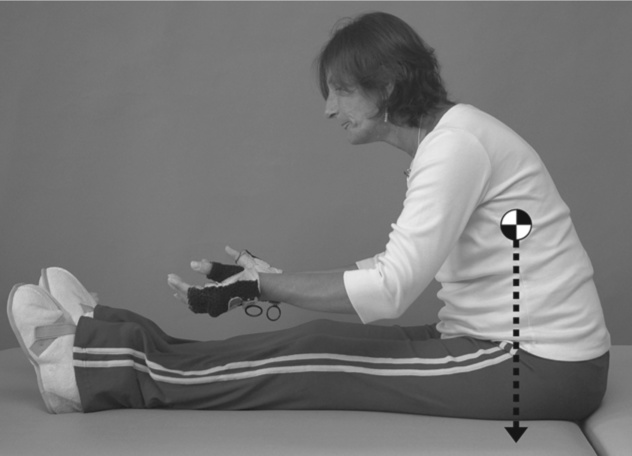

Patients with thoracic paraplegia and C6 tetraplegia also use compensatory postural adjustments to sit unsupported.1,3,7,8 Small postural adjustments are normally used by able-bodied people during performance of seated tasks. For example, when reaching sideways in sitting, able-bodied people laterally flex the trunk and neck away from the direction in which they are reaching. This minimizes sideway displacement of the centre of mass. Patients with spinal cord injury exaggerate postural adjustments to compensate for the loss of leg and trunk muscles. Thus to reach sideways with one arm they abduct the contralateral arm (see Figure 3.1). Similarly, to reach forwards with one arm they reach backwards behind the body with the other arm while at the same time extending the neck.

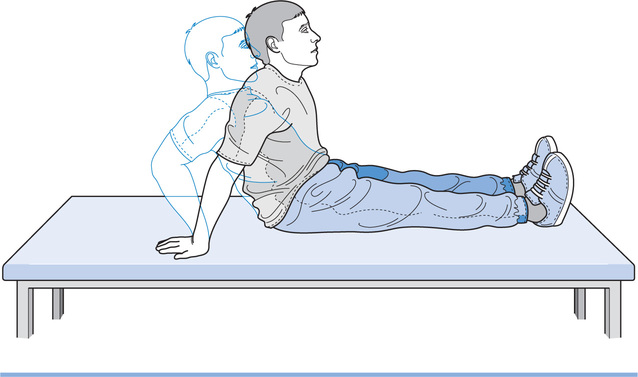

Patients with spinal cord injury and extensive trunk paralysis usually find it easier to sit with the knees extended (see Figure 3.2). This is because the paralysed hamstring muscles generate passive tension when the knees are extended. In turn, passive tension in the hamstring muscles generates hip extensor torques which prevent the trunk falling forwards.9 Patients will not fall backwards provided they are leaning far enough forward to position the centre of mass of the trunk anterior to the hip joints. This strategy for sitting is dependent on appropriate extensibility in the hamstring muscles. If the hamstring muscles are inextensible the hips cannot flex sufficiently to position the trunk’s centre of mass anterior to the hip joints. Consequently, the patient falls backwards. On the other hand if the hamstring muscles are highly extensible they do not constrain a forward fall (see Figure 3.3). Needless to say, the hamstring muscles can do nothing to prevent a sideways fall.

The paralysed hamstring muscles do not generate passive tension when the knees are flexed. Consequently, they cannot help maintain an upright sitting position when sitting over the side of a bed or on the front edge of a wheelchair (see Figure 3.1). It is therefore more difficult to sit over the side of a bed or on the front edge of a wheelchair than it is to sit in long sitting. In addition, some surfaces are more difficult to sit upon than others.3,10 For example, cushions which are very compliant (i.e. those filled with gel, air or fluid) are more difficult to sit on unsupported than relatively firm surfaces (see Chapter 13).3

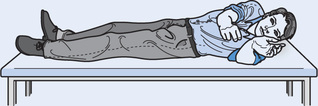

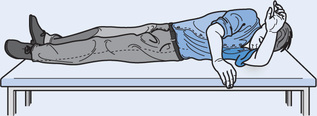

Rolling

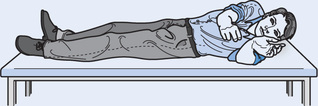

Able-bodied people roll by placing the leading arm across the body and using trunk and leg muscles to initiate rotation of the body. Patients with thoracic paraplegia and C6 tetraplegia cannot use trunk and leg muscles, so instead rely solely on the head and upper limbs to roll. They roll by rapidly swinging the arms across the body (see Table 3.1). This generates angular momentum which is transferred to the paralysed lower segments of the body, facilitating rotation. The position of the legs and head influence the ease of rolling. Most patients have less difficulty rolling if the ankles are crossed and the head is lifted off the bed. Rolling is also easier if the trunk is slightly stiff with loss of passive rotation.

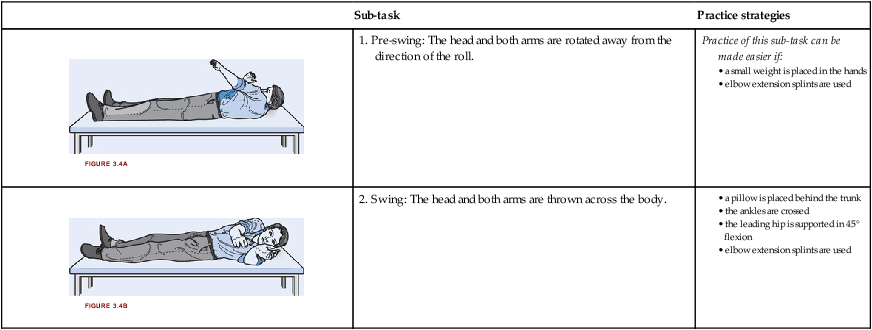

Table 3.1

A patient with C6 tetraplegia rolling onto the side (some practice strategies are described)

| Sub-task | Practice strategies | |

| 1. Pre-swing: The head and both arms are rotated away from the direction of the roll. | Practice of this sub-task can be made easier if: |

| 2. Swing: The head and both arms are thrown across the body. |

Lying to long sitting

Two strategies are used to move from lying to sitting. One involves rolling on to the side and then sitting up from a side-lying position (see Tables 3.2 and 3.3). This approach is cumbersome but relatively easy. Paralysis of the triceps muscles adds complexity because it limits the ability to push down through the hands to lift the body. Patients with C6 tetraplegia overcome this problem by maintaining the side-lying position and ‘walking’ one or both elbows around the body towards the knees (see Table 3.3, Figure 3.6e). From this position, the top arm is hooked under the top leg to pull up into sitting.

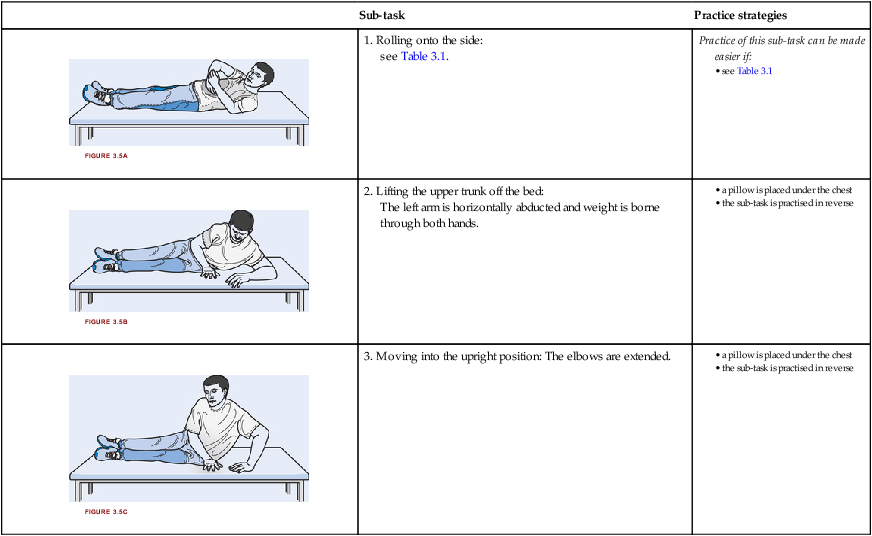

Table 3.2

A patient with paraplegia moving from lying to sitting (some practice strategies are described)

| Sub-task | Practice strategies | |

| 1. Rolling onto the side: see Table 3.1. | Practice of this sub-task can be made easier if: |

| 2. Lifting the upper trunk off the bed: The left arm is horizontally abducted and weight is borne through both hands. | |

| 3. Moving into the upright position: The elbows are extended. |

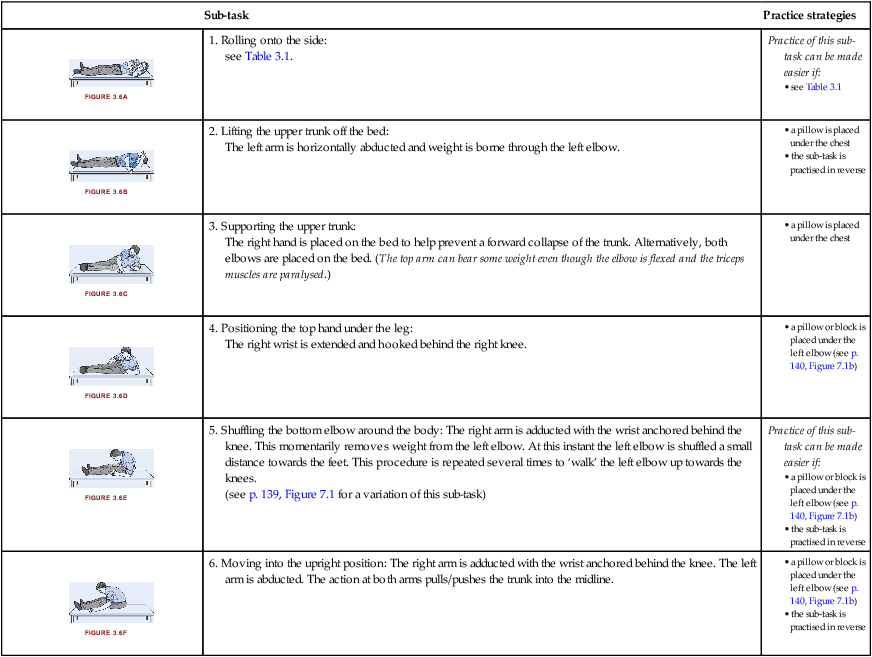

Table 3.3

A patient with C6 tetraplegia moving from lying to sitting (some practice strategies are described)

| Sub-task | Practice strategies | |

| 1. Rolling onto the side: see Table 3.1. | Practice of this sub-task can be made easier if: |

| 2. Lifting the upper trunk off the bed: The left arm is horizontally abducted and weight is borne through the left elbow. | |

| 3. Supporting the upper trunk: The right hand is placed on the bed to help prevent a forward collapse of the trunk. Alternatively, both elbows are placed on the bed. (The top arm can bear some weight even though the elbow is flexed and the triceps muscles are paralysed.) | |

| 4. Positioning the top hand under the leg: The right wrist is extended and hooked behind the right knee. | |

| 5. Shuffling the bottom elbow around the body: The right arm is adducted with the wrist anchored behind the knee. This momentarily removes weight from the left elbow. At this instant the left elbow is shuffled a small distance towards the feet. This procedure is repeated several times to ‘walk’ the left elbow up towards the knees. (see p. 139, Figure 7.1 for a variation of this sub-task) | Practice of this sub-task can be made easier if: |

| 6. Moving into the upright position: The right arm is adducted with the wrist anchored behind the knee. The left arm is abducted. The action at both arms pulls/pushes the trunk into the midline. |

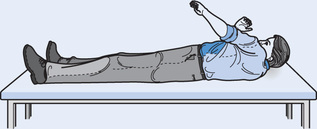

Another strategy for moving from lying to sitting involves using the upper arms to push directly into sitting from the supine position (see Figure 3.7). Patients with paraplegia place the hands behind the body. They then push down through the hands and use elbow extension to lift the trunk. Paralysis of the abdominal muscles makes it difficult to initially position the hands behind the body. Patients with C6 tetraplegia can also move directly from the supine position into sitting; however, a different technique is used which requires awkward positioning of the shoulders. Consequently, few patients master the technique and it often causes shoulder pain. It is therefore probably best avoided.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree