Traditional Medial Approaches to the Knee

Douglas D.R. Naudie

Robert B. Bourne

INTRODUCTION

The intent of this chapter is to provide an illustrative description of the traditional medial approaches to the knee for total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Since its inception, TKA has most commonly been performed using some variation of a medial parapatellar approach. Von Langenbeck originally described the dissection of the vastus medialis from the quadriceps tendon extending distally through the medial patella retinaculum and along the patellar ligament leaving a small cuff of tissue for closure (1). Insall described a modification of this approach whereby the quadriceps mechanism was opened with an incision in the quadriceps tendon dividing its medial one-third from the lateral two-thirds (2). Rather than skirting the medial border of the patella and leaving a cuff of tissue, he brought the incision straight distally, directly over the medial aspect of the patella. Insall believed that modification improved quadriceps healing (tendon to tendon) and was less disruptive to the extensor mechanism. Hofmann and associates advocated a subvastus approach to the knee, which divides the vastus medialis at the intermuscular septum leaving the muscle largely untouched (3). Other than some advocates of the mini-subvastus approach (see Chapter 3), the standard subvastus approach is not commonly used because of difficulties gaining exposure, risk of bleeding, and unclear benefits. Engh popularized the midvastus approach, which spares the quadriceps tendon but requires splitting of the muscle fibers of the vastus medialis obliquus muscles (4). This approach is utilitarian, has reduced the need for lateral release in some series, and has been embraced by enthusiasts of the minimally invasive techniques for knee replacement surgery (see Chapter 3).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

We prefer a traditional medial parapatellar arthrotomy for the vast majority of primary total knee arthroplasties at our institution, although the other referenced approaches to the knee are also appropriate and effective in select patients. For instance, the lateral parapatellar arthrotomy is particularly utilitarian in severe, fixed valgus deformities; and the extensile subvastus aproach is effective in cases of retained medial hardware on the distal femur (for example, from a previous distal femoral valgus osteotomy). However, some of these approaches have potential disadvantages. It has been our experience that the subvastus and midvastus approaches can be difficult in short, obese, and muscular individuals. These two approaches are also not conducive to the placement of a navigation array on the distal femur in cases in which we employ computer navigation. We have found that a lateral approach for severe valgus knees can compromise the ability to seal the arthrotomy from the subcutaneous space just beneath the skin incision.

The medial parapatellar approach can be used in virtually every case regardless of the preoperative deformity and range of motion. It is safe, extensile, and gives excellent access to the intra-articular and periarticular structures around the knee. This approach can be shortened to allow for a minimally invasive unicompartmental or TKA. If necessary, it can be extended both proximally and distally to allow for a quadriceps snip or tibial tubercle osteotomy, respectively. In fact, there are relatively few contraindications to its use. It does not, for instance, allow direct exposure to the popliteal fossa. It can even be used, if a very extensile approach is selected, for antero-lateral procedures such as lateral closing wedge high tibial osteotomies or other isolated procedures to the lateral side of the knee, although alternative laterally based incisions can also be selected for these procedures.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

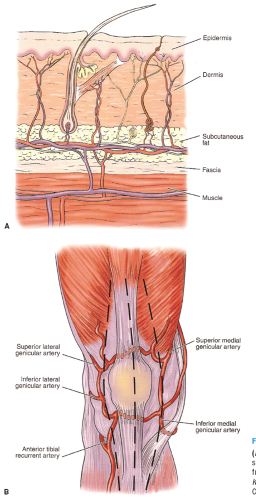

One of the important aspects of the preoperative planning for TKA is an understanding of the patient’s anatomy. The blood supply to the skin should be respected at all times, especially when prior incisions are present or multiple incisions are planned. Most of the blood supply to the skin arises from the saphenous artery and the descending geniculate artery on the medial side of the knee (6). The vessels perforate the deep fascia, form an anastomosis superficial to the deep fascia, and continue through the subcutaneous fat to supply the epidermis (Fig. 1-1A). There is little communication in the superficial layer; therefore, dissection should be deep to the fascia to maintain the blood supply to the skin.

The skin incision must be selected carefully. Because the fascial perforators arise from the medial side, the most lateral incision giving appropriate exposure should be used. Transverse scars can be crossed with a longitudinal perpendicular incision, as these do not appear to affect the healing of the vertical anterior medial approach. When possible, the anterior incision should incorporate other previous longitudinal incisions about the knee.

The blood supply to the skin should not be confused with the blood supply to the patella (5). The patella is separated from the skin by the prepatellar bursa, through which few blood vessels pass. The patella has a rich plexus of arteries surrounding it, arising from various sources (Fig. 1-1B). These branches include the four genicular arteries (superior medial, inferior medial, superior lateral, and inferior lateral) and the anterior tibial recurrent artery. Medial retinacular incisions will disrupt the three medial blood vessels contributing to the anastomosis around the patella. A recent study using laser Doppler flowmetry of 10 patients undergoing TKA did not demonstrate a significant change in patellar blood flow with a standard medial parapatellar approach (6). If a lateral retinacular release is added, however, one or both of the lateral vessels will be disrupted, potentially compromising patellar blood flow.

The nerve supply to the skin is similar in distribution to the blood supply. Branches of the saphenous nerve traverse laterally to the anterior aspect of the joint to provide cutaneous sensation. The infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve is typically transected with vertical skin incisions (particularly anterior and anteromedial incisions), resulting in an area of transient or permanent cutaneous hypoesthesia on the skin over the anterolateral knee. Patients should be made aware of this possibility. The terminal branches of the saphenous nerve innervate the vastus medialis. Electromyographic and nerve conduction studies have been performed and show no evidence of permanent vastus medialis muscle denervation with the midvastus approach to the knee (7,8).

TECHNIQUE

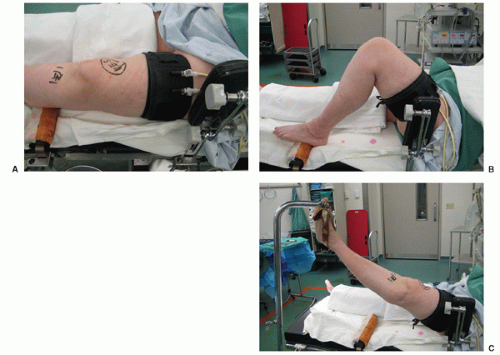

TKA is always performed with the patient in the supine position. The operating table should be level. A protective belt is applied across the upper body to allow tilting of the table as needed. A tourniquet is applied to the upper thigh after the correct patient and extremity have been identified and marked (Fig. 1-2A). The tourniquet should be applied snugly and as far proximally as practical. In the very obese patient, the fat may be pulled distally from beneath the tourniquet, causing it to bulge from the distal edge of the tourniquet. This prevents it from migrating and ensures that the tourniquet is placed as far proximal as practical. We use a commercially available footrest placed at the bulkiest part of the calf to suport the knee in flexion during the procedure. Alternatively, a sandbag can be used, provided it is taped securely to the bed. We also use a lateral bolster placed at the proximal third of the patient’s thigh to prevent external hip rotation (Fig. 1-2B). This step is particularly helpful in obese patients. The contralateral leg is well padded, especially under the heel, to reduce the risk of pressure sores.

There are many ways to prepare and drape a patient for TKA, but we have found that suspending the heel in a leg holder gives excellent access to the knee and allows surgical personnel to be available for other purposes (Fig. 1-2C). We shave the hair around the area of the planned incision just prior to sterile preparation of the leg. The nurses first scrub the leg with an iodine solution as the surgical team scrubs their hands. The entire leg is then prepared with an iodine solution. In patients with an iodine allergy, we use a chlorhexidine scrub and preparation solution. Additionally, alternative preparation solutions are emerging and being used with greater frequency.

The calf is supported with a sterile towel, the foot is removed from the footrest, and the remainder of the leg (including the foot) is prepared. A sterile drape is placed on the operating table. An impermeable, waterproof stockinette is placed over the prepped foot, after which a cloth stockinette is placed over the entire leg and over the tourniquet. A sterile U-shaped drape is placed proximally

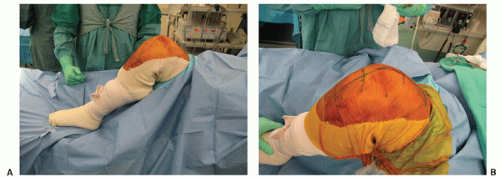

around the stockinettte at the level of the tourniquet. A limb extremity sheet with a rubberized central portion with a hole in it is then placed over the stockinette and pulled proximally to the tourniquet level (Fig. 1-3A). The foot and ankle are wrapped to prevent the stockinette from sliding during manipulation of the limb during the procedure. As an alternative to an impermeable stockinette, a cloth stockinette can be placed over the entire leg, and a sterile surgical glove can be placed over the foot. A window is cut in front of the stockinette on the anterior aspect of the knee, and the appropriate landmarks about the knee are palpated and marked with a sterile pen. The incision is then drawn, and transverse lines are made to assist with skin edge alignment at the time of closure. A betadine-impregnated sterile adhesive surgical drape is then applied to encricle the limb around the surgical site (Fig. 1-3B).

around the stockinettte at the level of the tourniquet. A limb extremity sheet with a rubberized central portion with a hole in it is then placed over the stockinette and pulled proximally to the tourniquet level (Fig. 1-3A). The foot and ankle are wrapped to prevent the stockinette from sliding during manipulation of the limb during the procedure. As an alternative to an impermeable stockinette, a cloth stockinette can be placed over the entire leg, and a sterile surgical glove can be placed over the foot. A window is cut in front of the stockinette on the anterior aspect of the knee, and the appropriate landmarks about the knee are palpated and marked with a sterile pen. The incision is then drawn, and transverse lines are made to assist with skin edge alignment at the time of closure. A betadine-impregnated sterile adhesive surgical drape is then applied to encricle the limb around the surgical site (Fig. 1-3B).

A tourniquet is used for all total knee arthroplasties, except in patients with known peripheral vascular disease and absent pulses confirmed by Doppler examination. These patients have a consultation with a vascular surgeon preoperatively. Relative contraindications to tourniquet use include obese patients with a short thigh (in which a tourniquet is potentially ineffective) or patients with known peripheral neuropathy. Patients with neuropathy should be warned that exacerbation of the neuropathy can occur with tourniquet use. The tourniquet is usually inflated to 300 mm Hg, to have the tourniquet at least 100 mm Hg above the systolic blood pressure. The pressure can be elevated as high as 350 mm Hg in hypertensive or obese patients. The leg is usually elevated for 30 seconds before inflating the tourniquet, or exsanguinations of the limb can be performed with an elastic bandage (e.g., Esmarch bandage). Prophylactic antibiotics are given within 30 minutes before tourniquet inflation.

Skin incisions must be modifed in the presence of prior incisions around the knee, as discussed previously, to avoid regions of potential skin necrosis. It is important to check that enough skin area is exposed for the entire incision. The initial exposure is done with the knee in flexion. Generally, we use a standard straight, vertical skin incision, measuring approximately 15 cm long. It is centered over the shaft of the femur, in its midportion over the patella, and distally just medial to the tibial tubercle. Using a new blade, the dissection is taken to the anterior border of the quadriceps tendon, patella, and medial border of the patellar tendon. It is important to avoid elevating large skin flaps and creating dead space. The subcutaneous dissection is concentrated on the medial side to allow for a medial parapatellar arthrotomy. Elevation laterally over the dorsal surface of the patella is kept to a minimum. In the severely obese patient, however, lateral dissection may be more extensive and necessary to create a subcutaneous pocket in which the patella may sit, allowing it to evert (Fig. 1-4A,B).

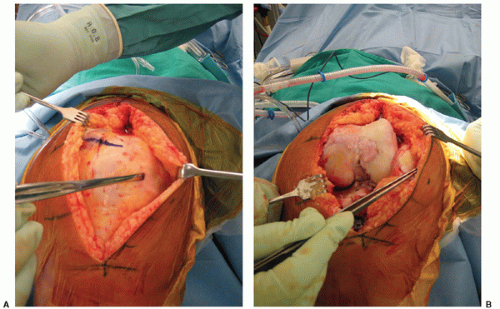

The quadriceps tendon is then identified. We have found that a Cobb elevator is useful to remove any tissue adherent to the quadriceps tendon. The medial and lateral edges of the arthrotomy at the level of the superior pole of the patella are marked with a sterile marking pen to facilitate an

anatomic closure at the end of the procedure. As discussed, there are many variations to the traditional medial parapatellar arthrotomy (Fig. 1-5A). We incise the quadriceps tendon in line with its fibers, about 0.5 to 1 cm from the vastus medialis. We extend the arthrotomy in a curvilinear fashion distally along the medial edge of the patella and gently back along the medial border of the patellar tendon (Fig. 1-5B). A soft tissue cuff is preserved at the superior pole of the patella and at the tibial tubercle to facilitate closure. The arthrotomy incision is made with a large scalpel blade through the medial retinaculum, capsule, and synovium.

anatomic closure at the end of the procedure. As discussed, there are many variations to the traditional medial parapatellar arthrotomy (Fig. 1-5A). We incise the quadriceps tendon in line with its fibers, about 0.5 to 1 cm from the vastus medialis. We extend the arthrotomy in a curvilinear fashion distally along the medial edge of the patella and gently back along the medial border of the patellar tendon (Fig. 1-5B). A soft tissue cuff is preserved at the superior pole of the patella and at the tibial tubercle to facilitate closure. The arthrotomy incision is made with a large scalpel blade through the medial retinaculum, capsule, and synovium.

FIGURE 1-4 (A,B) In this severely obese patient with a body mass index of over 45, lateral dissection is extended to create a subcutanous pocket in which the patella may sit during eversion. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree