Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients with Proximal Femoral Deformity

Daniel J. Berry

INTRODUCTION

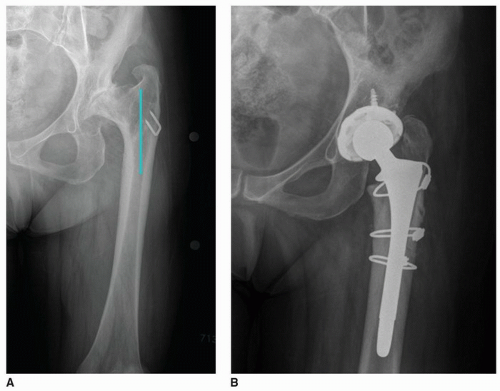

Proximal femoral deformity in the patient needing total hip arthroplasty (THA) presents both intellectual and technical challenges for the surgeon. If not optimally addressed, proximal femoral deformity can compromise a THA in three main ways: (a) the deformity can force the surgeon to put the femoral component in a position that is suboptimal for hip biomechanics or that compromises hip stability (Fig. 20-1); (b) the deformity can make it difficult to gain femoral component fixation; and (c) the deformity can increase the risk of complications during femoral preparation and implantation such as bone fracture, canal perforation, or abductor muscle damage. Thus, the triple goals of managing proximal femoral deformity during THA are to optimize hip biomechanics for good function of the arthroplasty and hip stability by choosing the best implant position, size, and design; gain reliable and durable implant fixation by optimizing the same three parameters; and minimize the risk of complications by choosing techniques that protect key structures such as the abductors, greater trochanter, and femoral canal integrity (Fig. 20-2). Not infrequently, the surgeon may need to make compromises between these three goals. For example, the surgeon may choose an implant that has a very high chance of durable fixation but only partially reproduces hip biomechanics.

FIGURE 20-2 A: Hip radiograph of patient with proximal femoral deformity. B: THA performed with modular implant, which allowed successful management of femoral angular and rotational abnormalities. |

INDICATIONS

The indications for THA in the presence of femoral deformity are very similar to those for any THA. The patient must have a combination of sufficient pain and/or disability related to the hip joint, in combination with sufficient radiographic joint damage, to justify the operation. The more severe the proximal deformity and the more complex the anticipated reconstruction, the greater the potential risk of complications or suboptimal outcome of the procedure. The patient and the surgeon must jointly factor these added risks into the pros and cons of the operation before making the ultimate decision about whether or not to perform the surgery. This inevitably means the threshold for surgery in terms of symptoms may be higher than in some patients with less deformity and hence less risk. Also the surgeon should try to give the patient a realistic idea of what functional level may be achieved in the setting of the deformity and in consideration of the constellation of factors that influence outcome such as muscle quality and acetabular bone deformity. This is important because in some cases, the anticipated level of function may not be the same as for patients with hip problems of shorter duration and with relatively minimal anatomic and soft tissue abnormalities.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

The usual contraindications to any THA apply, such as the presence of active local or distant infection, or insufficient symptoms to justify level of risk. Furthermore, in these sometimes very complex cases (as noted above), a surgery may not be indicated if the integrated risk of a serious complication seems prohibitively high compared to realistic and likely benefit.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Almost all THA surgery can benefit from careful preoperative planning, but there are a few circumstances in which it is more important—and in which more can be gained—by a systematic, careful, and thoughtful approach, than in THA in the setting of proximal femoral deformity. Likewise, and importantly, lack of preoperative planning in this setting risks real problems of avoidable complications and unanticipated intraoperative conundrums.

Proximal femoral deformities may be categorized by etiology or anatomically, and both classification system methods are useful (1). Understanding the etiology will provide clues to anticipated anatomic bony and soft tissue challenges and also to other important considerations. Classifying by anatomic geometry and location is the key to choosing an optimal implant and choosing and executing an optimal surgical technique (1).

The main etiologies of proximal femoral deformity are posttraumatic, postsurgical, developmental dysplasia, developmental following an insult to growth (such as Legg-Calve-Perthes disease or childhood sepsis), metabolic bone disease, and genetic abnormalities. Many of these etiologies have typical bone deformity patterns of both the acetabulum and femur and also specific considerations that are important for THA. Full accounting of these factors is beyond the scope of this book chapter, and the reader is referred to detailed discussions of THA for each diagnosis in this book or other sources. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile pointing out a few important considerations about several of these diagnoses. Deformity secondary to trauma or surgery can take on infinite anatomic variations, but in many cases, retained hardware will be present after previous procedures. Considering what hardware needs to be removed, how it will be removed, and what bone deficiency will be present after removal are all important. Ruling out infection after previous operative treatment or a known episode of previous infection also is important. Patients with hip dysplasia and other developmental abnormalities of the femur related to previous vascular injury or sepsis often have abnormalities of femoral version and associated acetabular deformities. Patients with musculoskeletal genetic disorders often have very abnormal bone size and unusual bone shapes. Patients with metabolic bone disease frequently have very abnormal bone density and may be at risk for bone stress fractures.

Anatomic classification of femoral deformity includes deformity of the greater trochanter, femoral neck, intertrochanteric area, subtrochanteric area, and femoral diaphysis. In each area, deformity may be angular, rotational, or one of bone diameter or length. Fully understanding the anatomy of the deformity is the first element in deciding how best to treat the deformity during THA.

Greater Trochanteric Deformity

When the greater trochanteric is lateralized, specialized treatment is rarely needed. When the greater trochanter overhangs the femoral canal, the surgeon needs to determine whether it is still possible to place a femoral component without severely damaging abductor attachments. If bone preparation for, and placement of, a standard implant will compromise the greater trochanter, the surgeon may use an implant that can be placed with instrumentation that accommodates the deformity. An alternative is to perform a greater trochanteric osteotomy to safely elevate the greater trochanter,

place the implant, then reattach the greater trochanter (Fig. 20-3). Methods of greater trochanteric osteotomy and reattachment are described in Chapters 4 and 5.

place the implant, then reattach the greater trochanter (Fig. 20-3). Methods of greater trochanteric osteotomy and reattachment are described in Chapters 4 and 5.

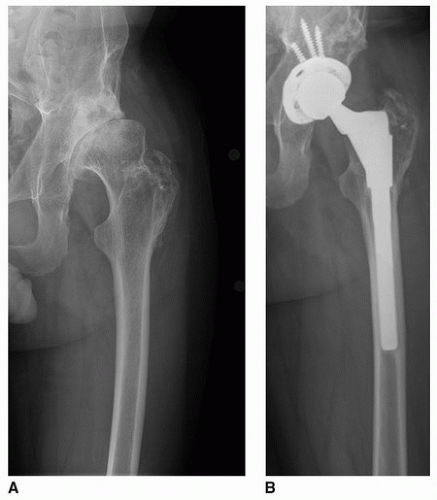

Femoral Neck Deformity

Minor femoral neck deformities may require a little deviation from standard THA techniques, but substantial deformities often require a change from either the surgeon’s standard implant or technique. Notable deformities of femoral neck anteversion, if not optimally managed, can lead the surgeon to place the implant in suboptimal rotation, which can lead to hip instability or suboptimal hip range of motion (e.g., excessive femoral anteversion can lead to an internal rotation gait and compromise hip external rotation). The most common methods of managing abnormal femoral neck anteversion are to (a) use a cemented component that allows adjustment within the confines of the proximal femur; (b) use an uncemented implant that has little metaphyseal flare and gets fixation in the diaphysis thereby bypassing the area of deformity; or (c) using modular uncemented implants that allow the stem to be placed in optimal anteversion even if fixation follows the anatomic shape of the femur (such as with modular proximal sleeves) (Fig. 20-4).

Abnormalities in femoral neck length or angle create challenges in reconstituting leg length and offset. First, the surgeon must decide if it is possible—or desirable—to try to reconstruct the hip to fully “normalize” hip biomechanics. This can be determined on preoperative template taking into account factors such as achievable leg length and desirable femoral offset. If the femoral neck is short, the surgeon may wish to gain some leg length and offset to optimize leg length, hip stability, and abductor lever arm. The amount of the increase in leg length and offset may be constrained by the soft tissue compliance and the amount of tension expected in the sciatic nerve.

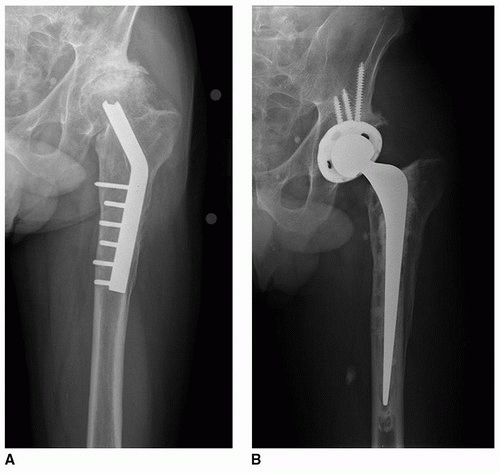

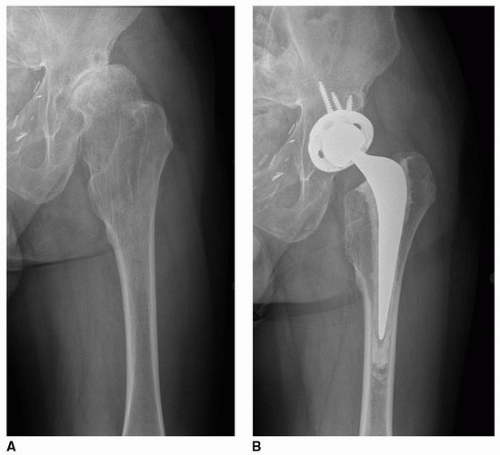

Intertrochanteric Deformity

Intertrochanteric area deformities create two main considerations: (a) how to obtain optimal femoral component fixation while maintaining good implant position and (b) how to manage the greater trochanter if it overhangs the femoral canal. If a cemented implant will be used, the deformity may be ignored or bypassed (Figs. 20-5 and 20-6). If an uncemented implant is used, the surgeon needs to determine if the deformity is sufficient to require the use of a special implant. Minor deformities

often may be handled with standard tapered implant designs. More notable deformities may be treated with implants that either bypass the deformity and gain fixation in normal diaphysis or provide for enhanced fixation in the metaphyseal area (such as in modular implants). Angular or rotational femoral osteotomies are rarely needed to accommodate intertrochanteric level deformities. Furthermore, osteotomies at this level leave small proximal fragments of bone, which are at risk for devascularization, fracture, and problems with bone fixation.

often may be handled with standard tapered implant designs. More notable deformities may be treated with implants that either bypass the deformity and gain fixation in normal diaphysis or provide for enhanced fixation in the metaphyseal area (such as in modular implants). Angular or rotational femoral osteotomies are rarely needed to accommodate intertrochanteric level deformities. Furthermore, osteotomies at this level leave small proximal fragments of bone, which are at risk for devascularization, fracture, and problems with bone fixation.

Subtrochanteric Level Deformity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree