Toe-to-Hand Transfers

CASE PRESENTATION

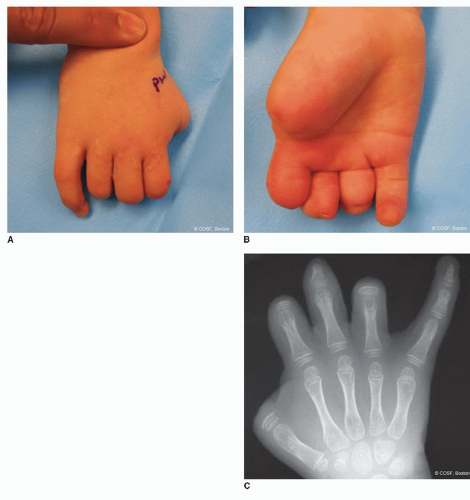

A 4-year-old child with amniotic band syndrome presents for evaluation of congenital hand deficiencies (Figure 46-1). The patient is otherwise healthy, and the contralateral hand is normal in appearance and function. Radiographs of the affected hand demonstrate a metacarpal hand with absent phalanges of the thumb and fingers. The patient and family now seek pediatric hand and upper extremity consultation for surgical options to improve hand function.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What are the indications for toe-to-hand transfers in children?

What are the patient- and condition-specific characteristics that favor toe-to-hand transfers?

How are toe-to-hand transfers performed?

What are the anticipated results and possible complications?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

To someone with nothing, a little is a lot.

—Sterling Bunnell

When caring for the child with congenital hand differences, the ultimate goal of the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon is to improve hand function by providing, if possible, sensate pinch and grasp. While the majority of conditions may be treated by reconstructing or augmenting existing anatomic structures, cases of severe deficiency provide greater challenges due to the absence of local anatomic structures. With the advent of microsurgical techniques, free toe transfers to the hand have provided the pediatric hand and upper limb surgeon a powerful tool to improve hand function and aesthetics.1, 2, 3, 4 and 5

Free toe-to-hand transfers offer a number of theoretical advantages. By definition, the procedure brings additional functional units to the deficient hand. No sacrifice of an adjacent, functional digit is required; this is particularly important in the hand without the normal complement of digits. Technically, transfers are facilitated by the similar surgical and functional anatomy shared between toes and fingers. And finally, the aesthetic and psychological benefits of a more normal appearing hand can be profound.6,7 Specific congenital deficiencies and post-traumatic scenarios are the usual indications for the rare pediatric toe-to-hand reconstruction.

Clinical Evaluation

Clinical evaluation begins with thorough history and physical examination. Prenatal history, associated medical conditions, patterns of hand use, and prior treatments should be carefully reviewed. Physical examination should focus both on the congenital deficiencies as well as the anatomic features of the structures present. Careful observation of spontaneous hand use will provide insight into the functional needs of the hand (e.g., the need for a thumb to pinch and grasp, the need for a stable ulnar post against which a native thumb may move in opposition). In systemic conditions such as amniotic band syndrome, physical examination of the feet is also important to confirm the presence of suitable donors. Radiographs of both the affected hand and potential donor foot are reviewed to assess the skeletal structures available to serve as a foundation for a transferred toe. If there is any suggestion of vascular abnormalities, or any history of prior surgical intervention, angiography is performed to map the vascular anatomy prior to surgery.

Surgical Indications

I think that the good and the great are only separated by the willingness to sacrifice.

—Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

The indications for toe-to-hand transfers in children remain controversial and continue to evolve. In general, toe-to-hand transfers may be considered in cases of congenital and post-traumatic deficiencies of the hand—and

particularly the thumb—in which local procedures or other, less complex procedures are not possible due to the absence of adjacent functional elements of the hand (Table 46.1). Specifically, in congenital cases, free toe-to-hand transfers may be considered in thumb aplasia without normal adjacent digits to pollicize, amniotic band syndrome with congenital amputations, symbrachydactyly, and other transverse failures of formation. Aphalangia with bilateral hand involvement is also considered an indication. In all these situations, there is an absent thumb, absent fingers, or both. With traumatic situations, it is often a failed or unattempted replantation, particularly of a thumb.

particularly the thumb—in which local procedures or other, less complex procedures are not possible due to the absence of adjacent functional elements of the hand (Table 46.1). Specifically, in congenital cases, free toe-to-hand transfers may be considered in thumb aplasia without normal adjacent digits to pollicize, amniotic band syndrome with congenital amputations, symbrachydactyly, and other transverse failures of formation. Aphalangia with bilateral hand involvement is also considered an indication. In all these situations, there is an absent thumb, absent fingers, or both. With traumatic situations, it is often a failed or unattempted replantation, particularly of a thumb.

The nature of the underlying condition is critical in patient selection and surgical indications. Survival and ultimate function of the toe-to-hand transfer are dependent in part upon the presence and quality of the proximal bony, tendinous, and neurovascular structures at the recipient site. Conditions in which the proximal anatomy is normal, such as in the congenital amputations seen with amniotic band syndrome or traumatic loss of the thumb, are more suitable candidates for free toe transfer.

Table 46.1 Strategies for thumb reconstruction for congenital deficiency or traumatic loss | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eaton and Lister8 have enumerated other characteristics that support—or argue against—the use of free toe-to-hand transfer (Table 46.2). Patient characteristics favoring toe-to-hand transfer include bilateral hand involvement, absent thumbs, younger age, presence of normal metacarpals, and normal proximal anatomy (e.g., amniotic band syndrome, traumatic amputation). Unfavorable factors include unilateral hand involvement excluding thumb, absent metacarpal heads, and older age in the setting of symbrachydactyly.

Finally, comprehensive discussion with the family must be made regarding the risks, benefits, realistic expectations, and alternatives to free toe transfer.7,9 This is best achieved longitudinally over multiple visits during the child’s first year of life or post-traumatic amputation, fostering a trusting relationship between surgeon and family and allowing for open discourse regarding treatment options.10

The optimal timing of toe-to-hand transfer remains equally controversial and highly patient and surgeon dependent. Advantages of earlier transfer in a congenital absence include faster and easier adaptation to the new functional element of the hand during a time in which the cortical representation of the thumb/hand is still forming. Disadvantages of early transfer include the technical challenges of performing microvascular surgery in the very young child. Patients with unilateral differences may achieve better functional results when transfers are done earlier in life, prior to the establishment of fixed patterns of use with the normal, contralateral hand.8,11 In bilateral hand involvement, particularly in the setting of symbrachydactyly where the proximal neurovascular anatomy is likely to be abnormal, later surgery can be entertained. As fine motor function continues to develop up to 3 years of age, we favor free toe transfers between 18 and 24 months of age. The technical aspects of the surgery are reasonable for skilled microsurgeons at this age, and the advantages of early learning are achieved.

Table 46.2 Factors for and against free toe-to-hand transfer for congenital hand differences | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

♦♦ Toe to Thumb for Congenital Differences

Surgery is best performed with a two-team approach, one to prepare the recipient site and one to harvest the donor12 (Figure 46-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree