CHAPTER 8 The thoracic and lumbar spine

The Spine: Anatomical Features

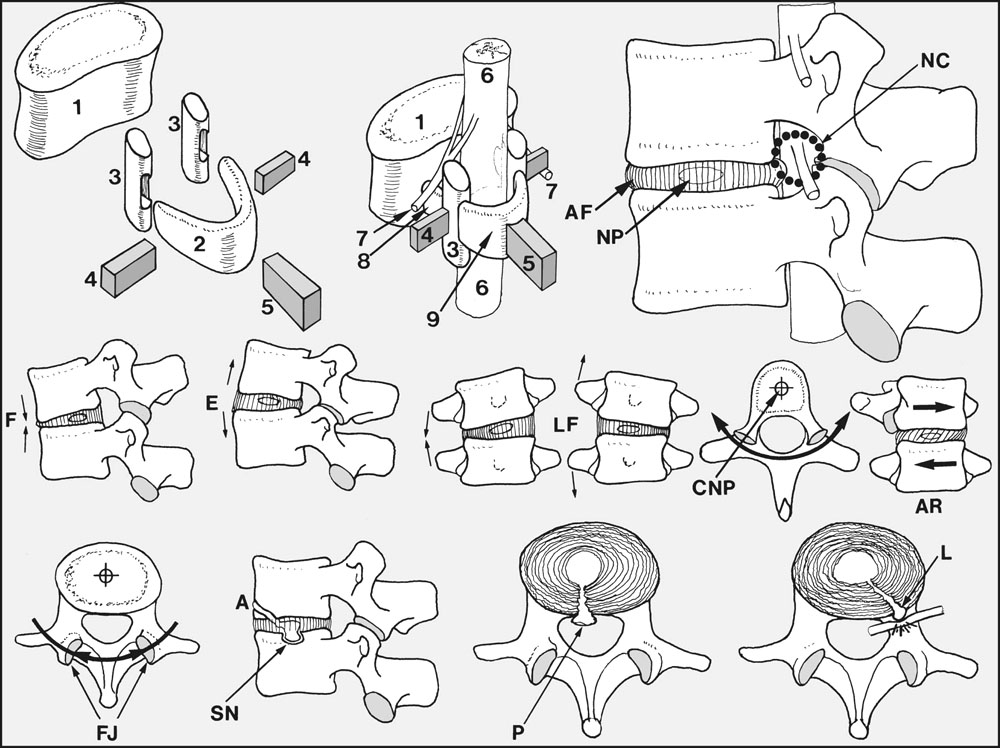

Movements between the vertebrae are possible in several planes, and the axes of these movements pass through the approximate centres of the intervertebral discs. At all levels of the spine, flexion (F) and extension (E), and lateral flexion (LF) to both sides are possible. In the thoracic spine, the plane of the facet joints lies in the arc of a circle which has its centre in the nucleus pulposus (CNP); as a result, (axial) rotation (AR) is possible in this part of the spine. In contrast, the orientation of the facet joints (FJ) in the lumbar region is such that rotation is blocked, i.e. virtually no vertebral rotation occurs in the lumbar spine.

Back Pain

In taking a history, examining and investigating a patient suffering from back pain, possible extraspinal causes should be excluded and an attempt should be made to place the patient in one of the three groups described above. Thereafter, and if possible, a more precise diagnosis may be attempted.

Important points in history-taking:

Scoliosis

In structural scoliosis there is alteration in vertebral shape and mobility, and the deformity cannot be corrected by alteration of posture. A careful history and examination is required in an attempt to find a cause and give a prognosis, the two factors on which treatment depends. Structural scoliosis may be congenital, the deformity being due, for example, to a hemivertebra (only half of a single vertebra is fully formed), fused vertebrae, or absent or fused ribs.

Scheuermann’s Disease (Spinal Osteochondrosis)

This condition (whose exact aetiology is unknown, although there is a strong familial tendency), results in a growth disturbance of the thoracic vertebral bodies which in lateral radiographs of the spine are seen to be narrower anteriorly than posteriorly (anterior wedging). There may be associated back pain. The diagnostic protocol for the condition specifies that no fewer than three adjacent vertebrae should have at least 5° of anterior wedging. The epiphyses of the vertebral bodies are often irregular and may be disturbed by herniations of the nucleus pulposus. Nuclear herniation may occur between the epiphyses and bodies anteriorly, or into the centre of the bodies (Schmorl’s nodes), thought to be due to ischaemic necrosis of the cartilaginous end-plates. Mobility is impaired, thoracic kyphosis is regular and often quite marked, and there is a compensatory increase in lumbar lordosis. Secondary osteoarthritic changes may supervene in the thoracic and lumbar spine.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

The disease is progressive, and although it sometimes arrests spontaneously at an early stage it usually leads to complete ankylosis of the spine, with characteristic changes in the radiographs (bambooing of the spine). Progressive flexion of the spine may be severe, so that forward vision becomes impossible as the head is flexed on to the chest. The sacroiliac joints are almost invariably involved at an early stage, and there may be fusion of the manubriosternal joint. There may be a history of iritis or its sequelae. The sedimentation rate is high (40–120 mm/h), rheumatoid factor is not present, and estimations of human leucocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) are usually positive. There is often associated anaemia, muscle wasting and weight loss.

Tuberculosis of the Spine

The aim of treatment is to overcome the infection, eliminate abscesses and sequestra, and promote sound fusion in the affected spinal segment to prevent any recrudescence. The mainstay of treatment is the use of the antituberculous drugs, although the emergence of resistant strains is causing problems. Sensitivity testing is advisable, and drugs should not be used in isolation. Drug therapy for periods up to 2 years was formerly advised, but it has been shown that regimens employing a combination of rifampicin and isoniazid for 6 months only seem equally effective. This is of particular importance where compliance is low. It has been noted that the addition of streptomycin to the drug regimen, bed rest, or a plaster cast do not seem to affect the outcome.

Metastatic Lesions of the Spine

Metastatic disease of the spine is seen particularly in the elderly and may be complicated by paraplegia. Back pain at night, pain unaffected by rest or activity, fatigue and weight loss are common features. The diagnosis is made on the radiographic findings. Treatment of the uncomplicated lesion is dependent on the nature of the primary tumour; in some cases deep X-ray therapy and supportive measures may help the local lesion and give relief of pain. Where paraplegia is present, decompression should be undertaken unless the case is terminal. In the patient with some pre-existing cardiovascular disease the possibility of an abdominal aneurysm should be considered; or if the pain is severe at night and there is weight loss, a further search for evidence of malignancy should be made. Primary tumours of the spine are rare; the common types are mentioned in Chapter 3.

Osteoarthritis (Osteoarthrosis)

Primary osteoarthritis of the spine is extremely common, especially in the elderly, and is often asymptomatic. In the majority of cases there are no obvious causes, apart from those associated with the degenerative processes of age. Sometimes obesity and excessive use of the spine by manual workers may be factors. In secondary osteoarthritis, previous pathology in the spine accelerates normal wear and tear processes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree