The Treatment of The Symptomatic Os Acromiale

Richard K.N. Ryu

Ryan M. Dopirak

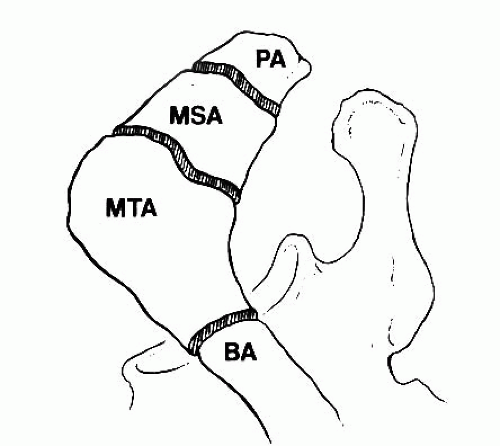

The acromion develops from four different centers of ossification: the preacromion, mesoacromion, meta-acromion, and basiacromion. These ossification centers appear between the ages of 14 to 18, with complete fusion typically evident by age 18 to 25.

An os acromiale is an anatomic variant that represents the failure of the acromial apophysis to fuse. It occurs in approximately 6% to 8% of the population and is bilateral in 33% to 41% of individuals. It has been observed to be more frequent in males than in females and is also more common in blacks than in whites. The most common site of an os acromiale is between the mesoacromion and the meta-acromion and is called a mesoacromiale.

Although often an incidental radiographic finding, an os acromiale may be pathologic in some patients. An unstable os acromiale may cause pain directly due to motion at the nonunion site. Additionally, it may be a source of symptoms due to external impingement with resultant rotator cuff pathology.

The initial treatment of a symptomatic os acromiale is typically nonoperative consisting of rest, activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy. Subacromial corticosteroid injections may also play a role in selected individuals although this may not be indicated in younger patients with significant rotator cuff pathology. When nonoperative measures fail to provide lasting symptomatic relief, surgery is often considered. Surgical options for an os acromiale include standard acromioplasty, complete fragment excision, or open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

There are currently no controlled studies comparing these various treatment options. Therefore, several factors should be considered during the decision-making process, including patient age and functional demands, location of the os acromiale, radiographic findings on MRI and bone scan, and intraoperative stability of the anterior fragment (1,2).

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History

A careful history is important in evaluating the patient with an os acromiale, as this may simply be an incidental finding unrelated to their true source of pain or dysfunction. However, when an os acromiale is symptomatic, it may cause symptoms by two different mechanisms. Motion between the fragments may be a direct cause of pain similar to that of a painful nonunion elsewhere in the body. In this scenario, patients typically report pain in the superior aspect of the shoulder, which may be exacerbated by overhead activity, heavy lifting, or repetitive use of the involved extremity.

Alternatively, an unstable os may cause a dynamic impingement syndrome where the mobile anterior fragment impinges upon the anterior aspect of the rotator cuff during deltoid contraction. In these patients, symptoms are those of a classic impingement syndrome. There may be pain in the anterolateral shoulder that is exacerbated by overhead activity and repetitive use of the extremity. Night pain and weakness are often present, especially in patients with concomitant rotator cuff pathology.

In some patients, the onset of symptoms may occur after a significant trauma to the shoulder with disruption of a previously stable fibrous union. However, in most patients the onset of symptoms is insidious without a significant traumatic event.

Physical Examination

A standard comprehensive physical examination is performed when evaluating the patient with an os acromiale. An unstable os may be painful due to motion at the nonunion site. In this situation, the examiner may elicit tenderness with palpation directly at the site of the os. Ballotment of the anterior mobile fragment can create motion at the nonunion site and reproduce the patient’s symptoms. It is sometimes possible for the examiner to appreciate motion of the anterior fragment although this is typically only possible in slender patients with a grossly unstable anterior fragment.

When the os acromiale causes symptoms due to a dynamic impingement upon the rotator cuff, physical findings are similar to those of a classic impingement syndrome. Patients demonstrate a painful arc of motion as

well as positive impingement signs. Active forward elevation in the scapular plane may be limited secondary to pain. Significant weakness of the rotator cuff may be present if concomitant rotator cuff pathology is present. Subacromial injection of local anesthetic is sometimes helpful in differentiating between weakness that is pain induced and weakness that is due to actual rotator cuff pathology.

well as positive impingement signs. Active forward elevation in the scapular plane may be limited secondary to pain. Significant weakness of the rotator cuff may be present if concomitant rotator cuff pathology is present. Subacromial injection of local anesthetic is sometimes helpful in differentiating between weakness that is pain induced and weakness that is due to actual rotator cuff pathology.

Imaging

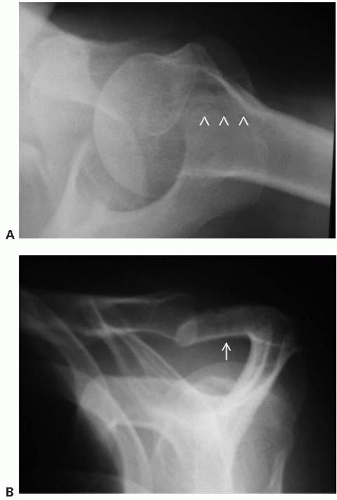

Standard shoulder radiographs are obtained when evaluating the patient with an os acromiale. A standard anteroposterior (AP) view can sometimes suggest the diagnosis of an os acromiale, as one may notice an apparent double density of the acromion. The scapular Y view can clearly demonstrate the os in most cases although in some patients this can be a subtle finding that may be overlooked. In a small number of patients, the Y view will reveal osteophytes on the superior aspect of the acromion. This is secondary to motion at the nonunion site and would be analogous to a hypertrophic nonunion elsewhere in the body. The axillary lateral is the view that is most essential in the diagnosis of the os acromiale. It will reliably demonstrate the presence of the os and will allow the surgeon to classify it according to its location (Fig. 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1. Radiographic examination of a mesoacromiale. A: Axillary view, white arrowheads indicate site of the mesoacromiale. B: Outlet view, white arrow indicates site of the mesoacromiale. |

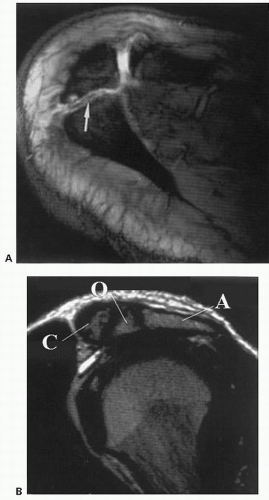

Although plain radiographs are a reliable and costeffective method of diagnosing an os acromiale, a shoulder MRI is also be obtained in many patients to rule out associated shoulder pathology. The os can be demonstrated on both the axial and the sagittal oblique MR images (Fig. 7.2). One must ensure that the axial cuts begin above the superior margin of the acromion or the diagnosis may be missed. On sagittal oblique views, it is important to recognize that the os can be mistaken for the acromioclavicular (AC) joint and may be overlooked.

When evaluating an os acromiale on MRI, an increased signal on the T2 sequences signifies the presence of fluid within the nonunion site and/or adjacent bone marrow edema within the fragment and is presumably due to repetitive motion and microtrauma. When present, many surgeons consider this finding to be diagnostic of instability of the anterior fragment.

FIGURE 7.2. MRI evaluation of an os acromiale. A: Axial image, white arrow indicates site of the os acromiale. B: Sagittal oblique image; A, acromion; O, os acromiale; C, clavicle. |

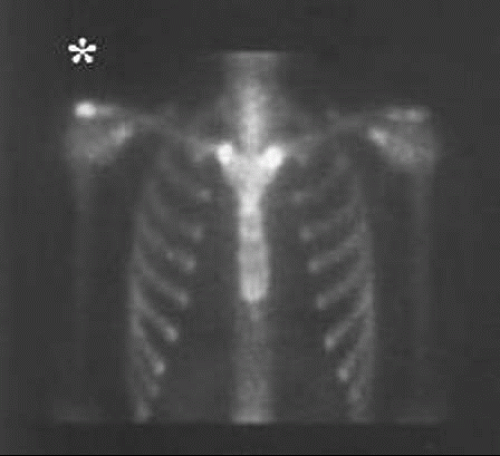

FIGURE 7.3. Tc 99 bone scan showing increased asymmetric uptake at site of os acromiale. Asterisk indicates site of os acromiale. |

Technetium (Tc 99) bone scanning is often utilized in the evaluation of an os acromiale. Significant asymmetric uptake in the acromion signifies instability of the anterior fragment with resultant motion and microtrauma at the nonunion site (Fig. 7.3). This test is an important part of the decision-making algorithm for the treatment of the os acromiale.

Classification

The acromion develops from four different centers of ossification: the preacromion, mesoacromion, meta-acromion, and basiacromion. When the diagnosis of os acromiale is made, it is commonly classified according to the anatomic location of the nonunion site. The ossification center directly anterior to the nonunion site is the fragment that is clinically unstable and thus the source of clinical symptoms; therefore, the os acromiale will derive its name from this fragment (Fig. 7.4).

FIGURE 7.4. Classification of os acromiale. PA, preacromion; MSA, mesoacromion; MTA, meta-acromion; BA, basiacromion. |

The most common type of os acromiale is a mesoacromiale, which represents a failure of fusion between the mesoacromion and the meta-acromion. Preacromial fragments occur less frequently than the mesoacromiale, but are not uncommon. In some patients, the preacromial fragment is small and may be overlooked on radiographic studies. The meta-acromiale is relatively uncommon.

When considering the diagnosis of os acromiale, it is important to remember that complete fusion of the acromial ossification centers does not typically occur until age 18 to 25. Therefore, in patients under age 25 an unfused acromial apophysis may represent nothing more than a normal developmental finding.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative

The initial treatment for an isolated os acromiale should be nonoperative consisting of rest, activity modification, NSAIDs, and formal physical therapy. Subacromial corticosteroid injections may also play a role in selected individuals although this may not be indicated in younger patients with significant rotator cuff pathology.

Nonoperative management has empirically been recommended for a minimum of 6 months. In the current medical environment, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to get physical therapy authorized for an extended period of time. Despite this fact, all conservative measures should be exhausted prior to consideration of surgical intervention.

In patients with a symptomatic os acromiale and a concomitant full thickness rotator cuff tear, extended nonoperative management may not be appropriate for all patients. In this situation, the decision-making process should be guided by standard protocols for the treatment of rotator cuff tears.

Operative Indications

When patients fail to improve with conservative measures as outlined above, surgical intervention may be considered. Several surgical options exist, including arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASAD), complete fragment excision, and ORIF. There are currently no prospective controlled studies comparing these various treatment options. Therefore, several factors should be considered during the decision-making process, including patient age and functional demands, location of the os acromiale, radiographic findings on MRI and bone scan, and intraoperative stability of the anterior fragment.

TECHNIQUE

Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression

The primary advantage of ASAD for an os acromiale is that it avoids the potential complications associated with ORIF

and complete fragment excision, including nonunion and symptomatic hardware, and deltoid dysfunction, respectively. However, if the os acromiale is unstable, resulting in painful motion at the nonunion site, simple ASAD is not likely to provide meaningful symptomatic relief as the underlying source of pathology has not been addressed.

and complete fragment excision, including nonunion and symptomatic hardware, and deltoid dysfunction, respectively. However, if the os acromiale is unstable, resulting in painful motion at the nonunion site, simple ASAD is not likely to provide meaningful symptomatic relief as the underlying source of pathology has not been addressed.

Hutchinson and Veenstra (3) performed ASAD in three patients with impingement syndrome and an associated os acromiale. After 1 year, all three patients had a recurrence of their symptoms. The authors concluded that simple ASAD was not appropriate for the treatment of os acromiale.

Aboud et al. (4) also evaluated outcomes after SAD for an os acromiale in 11 patients and found satisfactory results in only 64%. However, the SAD was arthroscopic in five patients and open in the remaining six patients. Furthermore, 5 of the 11 patients underwent concomitant rotator cuff repair. The diverse study group makes it difficult to draw conclusions from this study on the efficacy of ASAD for os acromiale.

Armengol et al. (5) performed modified acromioplasty in 23 patients with an os acromiale; seven of the surgeries were arthroscopic. In their technique, the undersurface was burred relatively aggressively so that only a thin cortical shell remained superiorly. Satisfactory results were achieved in 87% of patients.

Wright et al. (6) treated 12 patients (13 shoulders) with a mesoacromiale with extended arthroscopic acromioplasty. None of these patients had pain or tenderness at the nonunion site preoperatively. Their technique was similar to that of Armengol et al. (5) and consisted of more bone resection than the typical arthroscopic acromioplasty. The goal was to resect the mobile anterior lip to the point that it would be unable to impinge upon the rotator cuff while minimizing disruption to the deltoid and AC joint capsule. Satisfactory results were achieved in 85% of patients (6).

Based on the available literature, we believe ASAD may be indicated in selected patients with an os acromiale. The most critical factor in evaluating the patient with an os acromiale is determining whether the os is stable or unstable. ASAD should be performed only for an os acromiale that is determined to be relatively stable. This can be evaluated in three different ways. First, during the physical examination, assess tenderness to palpation directly at the site of the nonunion. Second, obtain a bone scan preoperatively to assess any asymmetric increased uptake at the site of the os acromiale. Third, evaluate the stability of the anterior fragment intraoperatively (Fig. 7.5). Through direct pressure on the superior aspect of the anterior fragment, significant motion may be appreciated if the fragment is grossly unstable (Fig. 7.6). In patients with no preoperative tenderness over the site of the os, a negative bone scan, and no evidence of instability intraoperatively, ASAD is the most appropriate treatment option for impingement of the anterior fragment upon the rotator cuff.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree