Diabetes mellitus is associated with many different neuropathic syndromes, ranging from a mild sensory disturbance as can be seen in a diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy, to the debilitating pain and weakness of a diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. The etiology of these syndromes has been studied extensively, and may vary among metabolic, compressive, and immunological bases for the different disorders, as well as mechanisms yet to be discovered. Many of these disorders of nerve appear to be separate conditions with different underlying mechanisms, and some are caused directly by diabetes mellitus, whereas others are associated with it but not caused by hyperglycemia. This article discusses a number of the more common disorders of nerve found with diabetes mellitus. It discusses the symmetrical neuropathies, particularly generalized diabetic polyneuropathy, and then the focal or asymmetrical types of diabetes-associated neuropathy.

The association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and neuropathy has been recognized for over 100 years, and soon it was realized that different subtypes existed, and so the first classification was proposed by Leyden in 1893, with hyperesthetic (painful), paralytic (motor), and ataxic forms of diabetic neuropathy. There are many varieties of neuropathy classified under the term diabetic neuropathy, some clearly linked to hyperglycemia and subsequent metabolic and ischemic change, others with compressive etiologies, and still others associated with inflammatory/immune processes. Many types of nerves can be affected, including large-fiber sensory, small-fiber sensory, autonomic, and motor, and findings may or may not be symmetric. Distal nerves and nerve trunks, nerve roots, and cranial nerves can be damaged. The most common of these syndromes is the diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy, which can produce mild distal sensory abnormalities and distal weakness. Some of the rarer associated conditions, such as diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, are important to recognize, however, as they can produce severe pain and weakness with considerable morbidity. Prognoses for the diabetic neuropathy syndromes are also varied and dependent on the underlying pathology, with some of them being progressive disorders and others being monophasic illnesses. This article first discusses the more diffuse neuropathic processes, and then the focal and asymmetrical forms. Since Leyden’s original classifications, many different classifications of diabetic neuropathy have been made. The two ways of classification preferred here are to divide diabetic neuropathies by the clinical pattern into symmetrical or asymmetrical forms ( Box 1 ) or to divide diabetic neuropathies based on the current understanding of pathophysiology ( Table 1 ).

Symmetric

Diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN)

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy (DAN)

Neuropathy with impaired glucose tolerance

Painful sensory neuropathy with weight loss, (diabetic cachexia)

Insulin neuritis

Hypoglycemic neuropathy

Polyneuropathy after ketoacidosis

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in DM

Asymmetric

Diabetic cranial neuropathy

Diabetic mononeuropathy:

Median neuropathy at the wrist

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow

Peroneal neuropathy at the fibular head

Diabetic radiculoplexus neuropathies (DRPN)

Diabetic thoracic radiculoneuropathy (DTRN)

Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy (DLRPN)

Diabetic cervical radiculoplexus neuropathy (DCRPN)

Reprinted from Sinnreich M, Taylor BV, Dyck PJB. Diabetic neuropathies classification, clinical features, and pathophysiological basis. The Neurologist 2005;11(2):63–79; with permission.

| Presumed underlying pathophysiology | Subtype of neuropathy |

|---|---|

| Metabolic-microvascular-hypoxic | Diabetic polyneuropathy |

| Diabetic autonomic neuropathy | |

| Inflammatory immune | Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy |

| Diabetic thoracic radiculoneuropathy | |

| Diabetic cervical radiculoplexus neuropathy | |

| Cranial neuropathies | |

| Painful neuropathy with weight loss, (diabetic cachexia) | |

| Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in diabetes mellitus | |

| Compression and repetitive injury | Median neuropathy at the wrist |

| Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow | |

| Peroneal neuropathy at the fibular head | |

| Complications of diabetes | Neuropathy of ketoacidosis |

| Neuropathy of chronic renal failure | |

| Neuropathy associated with large vessel ischemia | |

| Treatment related | Insulin neuritis |

| Hyperinsulin neuropathy |

Diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy

DPN is felt to result from nerve and blood vessel changes caused by chronic hyperglycemic exposure, and this can occur in either type 1 or type 2 diabetics. This syndrome typically presents as a slowly progressive primarily sensory deficit in a length-dependent fashion, with symptoms starting in the feet and spreading upwards, evoking the classic stocking-glove distribution. In more severe cases, it will involve motor fibers also, and can produce footdrop and other distal lower extremity weakness. It can involve both large and small fibers, and can have associated autonomic symptoms and signs. Upper extremity symptoms/signs can appear as part of the proximal progression of deficits, but in most cases, these are caused by superimposed mononeuropathies (median neuropathy at the wrist and ulnar neuropathy at the elbow) rather than spread of the underlying polyneuropathy .

Dyck and colleagues evaluated 380 patients in a cohort of diabetic patients representative of the community (the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study) and found that 66% of the patients with type 1 and 59% of the patients with type 2 DM had some type of neuropathy. In both the type 1 and type 2 patients, the most common neuropathy found was a DPN (the second most common neuropathy found in both of these groups was carpal tunnel syndrome). Despite the finding that DPN occurs commonly, most cases were asymptomatic and detected because of findings on clinical examination and electrophysiologic studies. Only 15% of the type 1 patients and 13% of the type 2 patients had a symptomatic polyneuropathy, and a very small percentage overall (6% of type 1 patients and 1% of type 2 patients) had severe symptomatic polyneuropathy with inability to walk on heels. These observations underscore the fact that most DPN is mild and that severe weakness only rarely occurs. In diabetic patients who have significant weakness, careful attention must be paid to other possible etiologies for their weakness, which can include other forms of diabetes-associated neuropathies, such as DLRPN (to be discussed later), and other types of neuromuscular disease that can occur independently of DM.

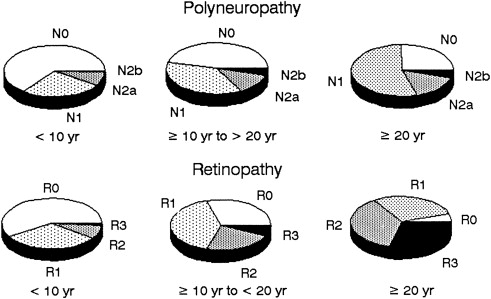

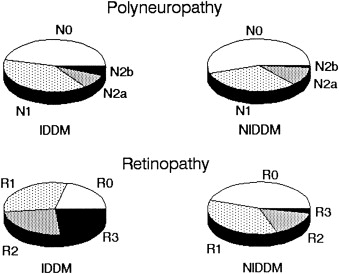

It has been shown that there are progressive subclinical nerve conduction abnormalities that precede the ultimate clinical diagnosis of DPN . Gregersen found a correlation between slowing of conduction velocities and duration of DM. A longitudinal study of risk factors for the severity of DPN found a correlation between severity and multiple other microvascular complications of diabetes such as retinopathy, proteinuria and microalbuminuria, and glycosylated hemoglobin. There was a strong correlation between the length of exposure of hyperglycemia and the degree of neuropathy ( Fig. 1 ), and between the degree of neuropathy and degree of retinopathy ( Fig. 2 ) .

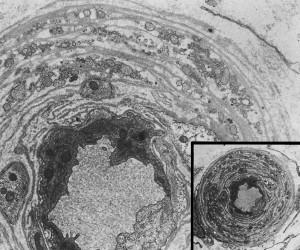

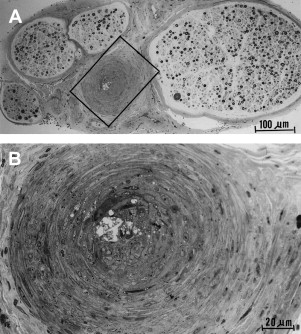

The etiology of DPN seems to relate to microvascular damage. The cause of the microvascular damage may be multifactorial but probably relates to chronic hyperglycemia-mediated direct metabolic effect. Sural nerve biopsies of diabetic patients who have peripheral neuropathy reveal increased numbers of endothelial nuclei and excess thickness of endoneurial microvessels caused by reduplication of the endothelial basement membrane ( Fig. 3 ), with a greater range in the thickness of vessel lumens . There is also macrovascular disease that is probably the cause of coronary artery disease and stroke, which is found in nerves but is not the cause of DPN ( Fig. 4 ).

Because of the significant morbidity that can occur with DPN and its association with hyperglycemia, there has been considerable interest in the possibility of preventing, slowing, or reversing neuropathy by improved control of blood sugar. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group studied 1441 insulin-dependent diabetic patients over a mean duration of 6.5 years and provided them with either conventional treatment, defined as one or two daily insulin injections, or intensive treatment, defined as at least three daily insulin injections or continuous insulin infusion with at least four glucose tests daily. They found that at 5 years, subjects receiving intensive therapy had a 64% less development of confirmed clinical neuropathy. Additionally, the prevalence of abnormal nerve conduction studies was lower by 44%, and abnormal autonomic function testing was lower by 53% in the intensively treated group . This is an encouraging finding, and shows that good glycemic control can delay and probably prevent the development of DPN. There continue to be efforts to find neuroprotective agents that may be useful for treatment once DPN has occurred, however.

Because of growing evidence that oxidative damage may play a significant role in the development of polyneuropathy, antioxidant agents such as lipoic acid have been studied. In an experimental rat model of diabetic neuropathy (streptozotocin-induced), the administration of intraperitoneal lipoic acid improved nerve blood flow and markers of oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner, and the conduction velocity of the digital nerve . Alpha-lipoic acid was evaluated in human patients who had symptomatic DPN as part of the SYDNEY trial, in which patients were treated with either intravenous alpha-lipoic acid 5 days a week for a total of 14 treatments or placebo. The primary endpoint of change in total symptom score (TSS, which assesses positive neuropathic symptoms) was met by showing a significant improvement in positive symptoms in the treated group versus placebo. There was also a significant improvement in the neuropathy impairment score (NIS) . The results of the ALADIN III study for alpha-lipoic acid were not as encouraging, however. This study randomized type 2 diabetic subjects who had DPN into three groups:

- 1.

Alpha-lipoic acid intravenously daily for 3 weeks, then orally for 6 months

- 2.

Alpha-lipoic acid intravenously daily for 3 weeks, then placebo orally for 6 months

- 3.

Placebo intravenously daily for 3 weeks, then placebo orally for 6 months

In this study, which evaluated treatment effect for a longer period of time than the SYDNEY trial, there was no significant difference after 7 months between the groups in TSS and in change in NIS between the alpha-lipoic acid group and the placebo group .

There may be a role of increased activity of the polyol pathway and increased glycation end products in the pathogenesis of DPN . Diabetic patients have been found to have higher levels of endoneurial glucose, fructose, and sorbitol than control patients . There is greater overall microvessel area in nerve of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats, and microvessel basement membrane thickening has been prevented with the use of an aldose reductase inhibitor . There are multiple trials studying the effects of various aldose reductase inhibitors, which block the polyol pathway, in an attempt to decrease or prevent the neuropathic complications of DM. Unfortunately, results have been mixed.

Judzewitsch and colleagues used the aldose reductase inhibitor sorbinil in 39 diabetic patients, and found that there were very mild improvements in nerve conduction velocities after 9 weeks of treatment. The clinical significance of these slight changes is indeterminate. Another study of sorbinil in patients who had DPN used sorbinil or placebo for a 6-month period, and found no major differences in clinical benefit between the two groups, and no difference on sensory threshold studies. There was significant benefit in the sorbinil-treated group in only a very limited number of electrophysiologic and autonomic parameters, such as conduction velocity in the posterior tibial nerve . Another aldose reductase inhibitor, tolrestat, was used to treat patients who had DPN over a 52-week period compared with placebo, and significant concordant improvement in paresthesias and motor nerve conduction velocities over placebo was found in the group receiving the highest tolrestat dose, 200 mg daily. Only 28% of the tolrestat-treated patients (at 200 mg/d), however, had concordant improvement at the 24-week evaluation maintained at the final 52-week evaluation . Krentz and colleagues treated patients with DPN with either ponalrestat, another aldose reductase inhibitor, or placebo for 52 weeks and found no significant differences between the groups in motor or sensory nerve conduction velocities, vibration thresholds, symptom scores, or autonomic function tests.

Recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF), which promotes the survival of small fiber sensory and sympathetic neurons, also has been studied in patients who have DPN, with the hopes that it could improve impaired nerve function. Apfel and colleagues performed a study in which 250 patients with symptomatic DPN were treated with 6 months of either rhNGF or placebo, and found a trend toward improvement in NIS(LL) in the treatment group. A trial evaluating the use of rhNGF in patients with HIV-associated sensory neuropathy found a benefit versus placebo in self-reported neuropathic pain intensity and pinprick sensitivity, suggesting that this may be a useful agent in different types of neuropathy . These studies helped bolster enthusiasm for the potential benefit of this agent. A larger randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 1019 patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes and DPN administered either rhNGF or placebo over a 48-week period. No significant change between baseline and the 48-week examinations in the NIS(LL) was found .

These results are somewhat disheartening, and it remains unclear if any of these agents ultimately will be helpful in treating DPN. At present, control of blood sugars and prevention are the most important ways of dealing with DPN.

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

Autonomic abnormalities can occur in DM with or without the presence of a large-fiber neuropathy. Many experts consider that DAN is really a part of the larger category of DPN. Low and colleagues reviewed the autonomic symptoms and standardized autonomic testing of patients with DM (types 1 and 2) and of control patients, and found that 54% of patients with type 1 diabetes, and 73% of patients with type 2 diabetes had objective autonomic impairment, but this was generally in the mild range. Only 14% of the diabetic patients in that study had moderate-to-severe generalized autonomic failure. The numbers were even smaller for the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study .

Autonomic failure can result in many troublesome symptoms, including orthostatic hypotension, nausea and constipation from abnormal gastrointestinal (GI) motility, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. The complex management of each of these problems is beyond the scope of this discussion, and often requires the coordinated care of multiple medical specialties.

Autonomic instability in these patients may result in greater surgical risk and morbidity; Burgos and colleagues prospectively studied 17 diabetic and 21 nondiabetic patients who had previously been given autonomic screening during elective ophthalmologic surgery and found that 35% of diabetics required intraoperative vasopressors compared with only 5% of the control group. Furthermore, the diabetics who required pressors had significantly greater autonomic impairment than those who did not. Investigators also have had concerns that DAN may be associated with sudden cardiac death, possibly related to abnormal lengthening of QT intervals . A recent review of cases of sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients, however, has revealed a greater correlation between sudden cardiac death and atherosclerotic heart disease and nephropathy than with DAN. The authors conclude that although there is an association between autonomic neuropathy and sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients, it is probably not the causative factor, and atherosclerotic heart disease is more important .

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

Autonomic abnormalities can occur in DM with or without the presence of a large-fiber neuropathy. Many experts consider that DAN is really a part of the larger category of DPN. Low and colleagues reviewed the autonomic symptoms and standardized autonomic testing of patients with DM (types 1 and 2) and of control patients, and found that 54% of patients with type 1 diabetes, and 73% of patients with type 2 diabetes had objective autonomic impairment, but this was generally in the mild range. Only 14% of the diabetic patients in that study had moderate-to-severe generalized autonomic failure. The numbers were even smaller for the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study .

Autonomic failure can result in many troublesome symptoms, including orthostatic hypotension, nausea and constipation from abnormal gastrointestinal (GI) motility, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. The complex management of each of these problems is beyond the scope of this discussion, and often requires the coordinated care of multiple medical specialties.

Autonomic instability in these patients may result in greater surgical risk and morbidity; Burgos and colleagues prospectively studied 17 diabetic and 21 nondiabetic patients who had previously been given autonomic screening during elective ophthalmologic surgery and found that 35% of diabetics required intraoperative vasopressors compared with only 5% of the control group. Furthermore, the diabetics who required pressors had significantly greater autonomic impairment than those who did not. Investigators also have had concerns that DAN may be associated with sudden cardiac death, possibly related to abnormal lengthening of QT intervals . A recent review of cases of sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients, however, has revealed a greater correlation between sudden cardiac death and atherosclerotic heart disease and nephropathy than with DAN. The authors conclude that although there is an association between autonomic neuropathy and sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients, it is probably not the causative factor, and atherosclerotic heart disease is more important .

Polyneuropathy associated with glucose intolerance

There is increasing interest in an association between impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), which does not meet the criteria for DM and the development of a chronic axonal polyneuropathy. Current American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines, recently revised in 2003, require a fasting plasma glucose from 100 mg/dL to 125 mg/dL, for a diagnosis of impaired fasting glucose, and a 2-hour glucose level from 140 mg/dL to 199 mg/dL (after a 75 g oral glucose load) for the diagnosis of IGT . It is estimated that approximately 33% of adults in the United States over 60 years old have either DM or impaired fasting glucose (diagnosed or undiagnosed) . This value was based on the earlier ADA criteria of impaired fasting glucose as a level between 110 mg/dL and 126 mg/dL, so the expectation is a higher overall incidence and prevalence with the new criteria. This percentage also does not take into account the greater number of patients with impaired glucose metabolism that may be detected through 2-hour oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT), which would be expected to increase the purported population at risk. Studies have shown higher yields for abnormal glucose metabolism in glucose tolerance tests than in fasting plasma glucose measurements .

Singleton and colleagues prospectively evaluated a cohort of 107 patients who had idiopathic symmetric distal peripheral neuropathy and found that 34% had IGT on an OGTT, which they noted was three times the prevalence of an age-matched historical cohort. Furthermore, only 72 of their subjects had an OGTT done, with a yield of 50% of the subjects receiving this test with an ultimate diagnosis of impaired glucose tolerance. The neuropathy pattern was predominantly sensory, as 81% of the patients with IGT had only sensory complaints, with 92% reporting neuropathic pain as a dominant symptom. Electrophysiologic findings revealed over half (61%) of the IGT patients had decreased sural sensory amplitudes, whereas only 21% had a decreased peroneal motor amplitude. Sumner and colleagues reported on 73 patients who had a peripheral neuropathy of unknown cause, and found that 56% of them had abnormal findings on an OGTT (26 of them with IGT and 15 with DM). The authors found that the patients with IGT had less severe neuropathy and more predominant small fiber involvement than the diabetic patients. Hoffman-Snyder and colleagues retrospectively assessed 100 consecutive patients with an idiopathic chronic axonal neuropathy, who had fasting plasma glucose and a 2-hour OGTT. By the new ADA 2003 criteria, 39% of these patients had an abnormal fasting blood sugar, 36 of whom were in the range of impaired fasting glucose, and three of whom were in the diabetic range. Using the OGTT, even a higher percentage (62%) of the patients had an abnormal glucose metabolism, 38 with IGT and 24 with DM. These rates were higher than previously published age-matched controls (33%) . The authors commented that abnormal glucose metabolism was found at similar rates in sensorimotor, sensory, and small fiber neuropathies.

There is also some pathologic evidence of increased endoneurial capillary density in sural nerves of patients who have IGT progressing to DM compared with patients who have stable IGT, indicating that microvascular abnormalities are occurring in a prediabetic state . Skin biopsies of patients with neuropathy and IGT have demonstrated abnormal intraepidermal nerve fiber density . Smith and colleagues showed that patients who had IGT and neuropathy had significantly improved proximal intraepidermal nerve fiber density and improved response on OGTTs after 1 year of a diet and exercise counseling program compared with their baseline OGTTs. The authors noted, however, that patients who had absent dermal plexus on the initial biopsy were unlikely to have significant reinneravation on repeat biopsy.

Not all evidence, however, has been supportive of the association between IGT and neuropathy. Eriksson and colleagues performed nerve conduction studies, heat, cold and vibration threshold testing, and autonomic function testing on patients who had IGT, diabetic patients, and nondiabetic controls. They found that aside from significantly more abnormalities in heart rate with inspiration and expiration (suggestive of vagal nerve involvement), there were no other parameters that were significantly different between their patients with IGT and controls . Hughes and colleagues studied 50 patients who had chronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy and 50 control patients, with OGTT and fasting plasma glucose analysis, and did not find an association with IGT and neuropathy after adjusting for age and sex. The lack of a significant association is particularly compelling, given that there was an active control group in the study, as opposed to most of the other studies cited, which used historical control data as a comparative measure of prevalence of IGT in the general population.

At this point in time, the relationship between IGT and peripheral neuropathy needs further clarification. Although a very interesting and potentially important hypothesis, the association has not been proven definitely. A large epidemiology study has been begun looking at IGT and neuropathy in Olmsted County, Minn.

Acute painful diabetic neuropathy with weight loss

Cachexia and weight loss may be seen in association with DM . This acute painful neuropathy with weight loss is considered by some authors to be a clinical entity separate from DPN . This syndrome also is known as diabetic cachexia and is not related to the severity or duration of DM and has a monophasic course, usually over months. The illness begins with sudden, profound weight loss followed by severe pain, often burning, and excessive sensitivity to touch (allodynia) of the lower legs and feet. Autonomic features other than impotence are usually absent. Some experts have argued that this entity is part of the spectrum of DPN with the same underlying mechanism and pain fibers being predominantly involved. This monophasic course, the lack of correlation between DM duration, and the neuropathy with associated weight loss, make it unlikely to be part of DPN. In contrast, the occurrence of neuropathy in early DM, the associated weight loss, and the monophasic course are features that typically are found in DLRPN, which is described later . DLRPN has been shown to be caused by microvasculitis and ischemic injury. The pathological basis of acute painful diabetic neuropathy with weight loss has not been determined, but an immune mechanism seems likely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree