Chapter 79 The Problem Wound

Coverage Options

Local Soft Tissue Manipulation

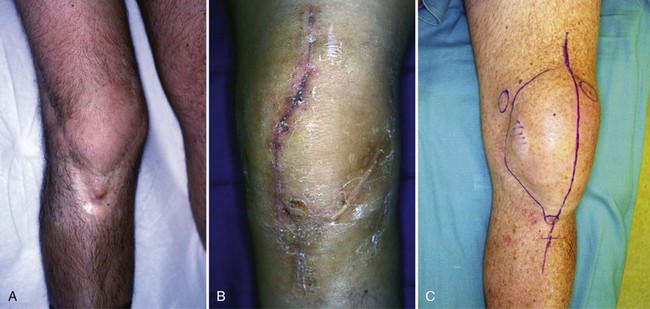

Certain patients have multiple existing incisions or other local conditions that might portend primary wound-healing difficulties after total knee arthroplasty (Fig. 79-1). Anticipating which patients will have healing difficulties allows us to plan preoperatively for primary healing and to provide healthy soft tissue coverage; consequently, wound compromise is avoided, and long months of recovery, delay in motion gains, and other complications that occur when healing fails to progress as expected are avoided. In these patients, we will use a sham incision, tissue expansion, or flap coverage from a local or distant source.

Sham Incision

The sham incision, and probably tissue expansion as well, makes use of the delay phenomenon to increase tissue survival. Despite some controversy regarding the actual mechanism for effecting delay, there is no doubt that delay works when planned with care. When a surgical wound is incised with a plan to delay, hypertrophy and reorganization of vessels along the axis of the delayed tissue occur and result in improved surviving length.2 Whether the success of the delay technique is due to vascular ingrowth in response to ischemia, enlargement of existing vessels, or conditioning of tissue to ischemia is unknown.7 One week is sufficient time for the delay phenomenon to occur; longer time provides no advantage in the number or size of improved vasculature.10,21,23

The indication for a sham incision is a situation wherein the likelihood of primary healing is reasonable but some question remains regarding the health and vascularity of the local soft tissue. The disadvantage of this approach is the potential for tissue loss in the wound created by the sham incision. Although it is certainly preferable to have tissue loss occur in the knee before placement of a prosthesis, if tissue necrosis occurs after a sham incision, the surgeon is now faced with addressing a nonhealing wound in a patient who has yet to undergo total knee arthroplasty. In an attempt to avoid this situation, to provide adequate soft tissue coverage, and to increase vascular supply to the skin over the knee before joint replacement in situations of marginal supply, tissue expansion has proved to be an excellent technique (Fig. 79-2). Our indications for its use have evolved over the last decade, as have our contraindications. We now find that this coordinated approach serves as a satisfactory solution in selected patients.

The Problem Wound

Skin Grafting

Skin grafting removes a dermal-epidermal layer of skin from a donor site and applies it to a suitably prepared recipient bed. The bed must have appropriate vascularity to allow the skin graft to survive initially by serum imbibition for 48 hours, after which the skin graft is penetrated by ingrowth of vascular channels; by about day 5 or 6 after grafting, circulation is reestablished.1,4,5 The bed on which the graft is placed must be free of infection with excellent hemostasis (Fig. 79-3). Once in place, the graft must be well fixed with suture, a compressive dressing, or application of the wound vacuum-assisted closure (V.A.C. Kinetec Concepts, Inc., San Antonio, Tex). Stability will allow revascularization.

The skin graft donor site ordinarily heals by secondary intention and must be protected from trauma and invasion of bacteria until healing occurs. It may be dressed with Xeroform (Covidien, Mansfield, Mass) and allowed to air-dry, or it may be dressed with an occlusive dressing, as the surgeon prefers. Some evidence suggests that occlusion until the donor site heals is more comfortable for the patient.27 Once the donor site has epithelialized, long-term effects such as pruritus, sensitivity, pigment changes, and even scar hypertrophy may occur. These conditions are ordinarily self-limited, but if persistently troublesome, they may be addressed with antipruritics, antihistamines, lubricants, or topical silicone sheeting such as Mepiform (Molnlycke Health Care, Oldham, United Kingdom) or Cica-Care (Smith & Nephew, Hull, United Kingdom) (Fig. 79-4). Corticosteroid injection and even irradiation may be indicated in situations where true keloid formation occurs, although these instances are rare.19

Muscle and Myocutaneous Flaps

The local workhorse for coverage of defects about the knee is the gastrocnemius muscle or myocutaneous flap. The most superficial muscle layer of the posterior region of the calf, this muscle has a medial and a lateral head, each of which is usually supplied by an independent artery.18 Each head of the muscle originates on its respective posterior surface of the femoral condyle, with the medial head originating medially and the lateral head laterally. The medial head is usually the longer of the two heads and extends farther distal than the lateral head does; the two heads are divided by a median raphe, which also marks a clear division of their separate vascular territories. The raphe transitions to the musculotendinous junction as the gastrocnemius contributes to the broad, substantial Achilles tendon. Each gastrocnemius muscle head is a type II flap anatomically, with a single arterial pedicle providing blood supply supported by at least one secondary pedicle from the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries.25 The medial and lateral heads are supplied by the medial and lateral sural arteries, respectively. The arteries arise at (60%) or above (32%) the joint line of the knee.22 Most commonly, the medial sural artery arises slightly more proximally than the lateral artery; few, if any, arterial communications occur between the medial and lateral heads within or across the median raphe.25 Because of this independent and very reliable blood supply, each head can be taken separately with or without overlying skin for coverage. Each sural artery has a 6- to 8-cm course before it penetrates the deep surface of the muscle and then arborizes and divides within that muscle.

This muscle provides a number of perforators to the skin overlying the muscle and distal to it and can be taken with a sizable skin paddle when needed. The perforators are located just off the midline of the posterior of the calf. The first of those over the medial head is approximately at the level of the tibial plateau, the next is about 3 cm lower, and the last perforating branch is close to but above the musculotendinous insertion into the Achilles tendon.3,6,26 Provided that these perforators are identified and protected, a medial gastrocnemius flap can be harvested with overlying skin to within 5 cm of the medial malleolus with continuous Doppler assessment of perforators to verify viability as the flap is manipulated.8 The arc of rotation of the medial gastrocnemius muscle flap allows coverage of the proximal third of the tibia, the medial knee joint, the tibial tubercle, and the patella (Fig. 79-5). When taken as an extended flap with overlying skin, coverage can be achieved from the middle third of the tibia to the suprapatellar region. If more extensive reach is needed, the muscle origin can be taken down from the posterior surface of the medial femoral condyle. This technique provides adequate release if there is any tension on the closure and can add almost 2 cm of flap advancement when needed. If the required coverage is deficient in width rather than length, the deep muscle surface can be incised through its fascia and the muscle spread to increase its width of coverage.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree