Chapter 2 The Patient-Centered Medical Home

History

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) used this concept to expand the characteristics based on discussions defining the future of family medicine. These characteristics described the “personal” medical home, which focused on bringing attention to the importance of continuous, relationship-centered, whole-system, comprehensive care for communities (Martin et al., 2004). In 2007 the AAP, AAFP, American College of Physicians (ACP), and American Osteopathic Association (AOA) collaborated to define further the foundational principles of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH; Table 2-1). The goal of the medical home is to emphasize the importance of primary care in improving quality of care, health outcomes, and patient experience, with improved cost-efficiency.

Table 2-1 Principles of a Patient-Centered Medical Home

Modified from American College of Physicians. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home, March 2007.http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/medical_home/approve_jp.pdf.

Healing, Curing, and the Goals of the Medical Home

Medicine in general and primary care in particular involve constant tension between diagnosis and elimination of the disease (cure) on one hand and alleviation of suffering in the context of disease and treatment (healing) on the other. In this context, healing means helping patients cope emotionally and practically with whatever condition they face, even when cure is not possible.

Balancing Treatment of Disease and Promotion of Health

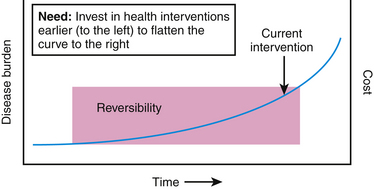

Behaviors that have the greatest impact on preventing chronic disease and its progression are (1) reducing exposure to toxic substances (tobacco, alcohol, drugs, pollution), (2) movement and exercise, (3) healthy diet, (4) psychosocial integration and stress management, and (5) early disease detection and intervention (Jonas, 2009; McGinnis, 2003). For these behaviors to have an impact, the health home will need to be financially supported and have the goal of health as its primary focus. This will require new forms of funding that go beyond the disease-focused throughput model of payment. A primary care clinic that only works from this model will encourage shorter office visits while promoting reliance on expensive technology that often suppresses symptoms without addressing its cause. The health home will push the curve in Figure 2-1 to the left and will involve professionals who specialize in health promotion (or creation) to flatten the curve and reduce the need for the “disease care” teams currently well established in the tertiary care setting.

Establishing an Optimal Healing Environment

“Meaning” and “context” effects are rooted in relationship-centered care, including empathy, trust, empowerment, and hope. Research on one of the most frequently prescribed drugs in primary care, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), shows that these work only about 6% to 9% better than placebo (Kirsch et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2008). Both placebo and drug work well and are often almost 60% effective. Therefore, if the drug only accounts for 9% of this effect, which factor accounts for the majority of the healing influence? Maybe researchers are not giving enough credit to the clinician and the nonspecific variables that surround the prescribing of the pill. Maybe it is simply the act of listening to people who are suffering and giving them a sense of understanding that there is something they can do to overcome the suffering. Maybe it is the interaction between two people before the medicine is prescribed that has the greatest healing effect. Psychiatrists gifted at developing a trusting relationship were found to have better effects with placebo in treating depression than their colleagues less talented at developing relationships who used active drug (McKay et al., 2006). Acupuncture delivered with a greater ritual produces better effects than the same points treated with less ritual (Kaptchuk et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2009). Maybe it is the cost. Drugs that cost more (up to a certain point) work better in pain treatment than the same drugs that cost less (Waber et al., 2008).

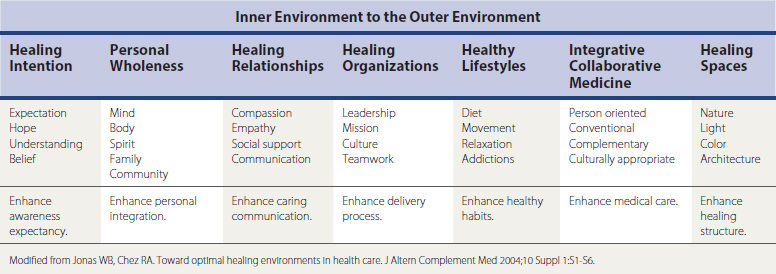

Family physicians do not need to wait for further research to create an OHE for patient care. Physicians already know that the factors summarized in Table 2-2 will help encourage the healthy unfolding of complex systems. The most important part in influencing healing in others is focused on the left side of the table and starts with a self-reflective, internal process. Family physicians first need to understand the importance of continuously exploring their own health, so that they are prepared to do the same for their patients.

Investing in Relationship

The medical home is just that, a “home” where someone feels welcome, known, and part of a community. The ongoing relationship with patients provides insight into the complexity of their health care needs and honors the interaction between multiple health perspectives. It allows the clinician to use evidence-based guidelines while realizing that variability is the norm. The best care for one individual may not be best for another. Patient-centered care recognizes that care should be focused on the needs of the individual patient, not simply on a disease state. Ideally, the goal should be “relationship centered,” encouraging attention to the unique needs of the patient to be well. Thus, creating healing relationships is a core goal of an effective medical home (Chez and Jonas, 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree