Chapter 40 Urinary Tract Disorders

Evaluation of the Urinary Tract

Physical Examination

Examination of the external genitalia in men may reveal penile lesions, regional adenopathy, or disorders of the scrotum and testicles. Uncircumcised men should have the foreskin retracted to rule out phimosis and visualize the glans. Careful palpation of the testicular complex is needed to detect and differentiate masses and anatomic abnormalities. Digital rectal examination (DRE) can estimate prostate size and detect masses or inflammation. It is usually performed with the patient leaning forward on the examination table with his elbows bent. Prostate tenderness, warmth, or a boggy consistency suggests prostatitis. Prostate enlargement consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia is typical in older men. Masses or asymmetry may indicate a tumor.

Laboratory Tests

Urinalysis

Inspection

Normal urine color varies from clear (dilute) to yellow to deep golden and cloudy. Many substances can cause urine color to appear abnormal (Table 40-1). Cloudy urine may be caused by infection (pyuria), but the most common cause is phosphaturia, in which phosphate crystals precipitate in alkaline urine. Microscopic analysis can differentiate these two entities. A strong or foul-smelling sample does not necessarily indicate infection. Urine odor may change because of dietary intake (e.g., asparagus), medications, illness, or concentration. Fecal odor suggests gastrointestinal-vesical fistula.

Table 40-1 Factors Affecting Urine Color

| Color | Causative Factor |

|---|---|

| Colorless | Very dilute urine; overhydration |

| Cloudy, milky | Phosphaturia; pyuria; chyluria |

| Red | Hematuria; hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria; anthocyanin in beets and blackberries; chronic lead and mercury poisoning; phenolphthalein (in bowel evacuants); phenothiazines (e.g., prochlorperazine [Compazine]); rifampin |

| Orange | Dehydration; phenazopyridine (Pyridium); sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) |

| Green-blue | Biliverdin; indicanuria (tryptophan indole metabolites); amitriptyline (Elavil); indigo carmine; methylene blue; phenols (e.g., IV cimetidine [Tagamet]; IV promethazine [Phenergan]); resorcinol; triamterene (Dyrenium) |

| Brown | Urobilinogen; porphyria; aloe, fava beans, rhubarb; chloroquine, primaquine; furazolidone (Furoxone); metronidazole (Flagyl); nitrofurantoin (Furadantin) |

| Brown-black | Alkaptonuria (homogentisic acid); hemorrhage; melanin; tyrosinosis (hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid); cascara, senna (laxatives); methocarbamol (Robaxin); methyldopa (Aldomet); sorbitol |

From Hanno PM, Wein AJ. A Clinical Manual of Urology. Norwalk, Conn, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1987, p 67.

Dipstick Urinalysis

pH

Average urinary pH is usually acidic, ranging from 5.5 to 6.5. It reflects the serum pH except in patients with renal tubular acidosis (RTA) (Simerville et al., 2005). These patients have alkaline urine because the kidneys cannot acidify urine. Type 1 RTA will always have alkaline urine, whereas urine in type 2 RTA may become acidic as the acidosis worsens. Urine infected with urease-producing organisms such as Proteus species becomes alkaline.

Protein

Urine dipsticks are very sensitive and specific for albuminuria. The reagent color change roughly corresponds to the protein concentration in the sample (Table 40-2). Very dilute, alkaline, or nonalbumin proteinuria may cause false-negative results. Microalbuminuria screening usually requires a separate dipstick designed specifically for this purpose. A urine protein electrophoresis is needed to evaluate nonalbumin proteinuria, such as globulinuria or Bence Jones protein.

Table 40-2 Dipstick Protein Findings

| Dipstick Color | Estimated Corresponding Protein Level (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Yellow | Negative (no protein) |

| Yellow-green | Trace (10-20) |

| Green | 1+ (30) |

| Dark green | 2+ (100) |

| Green-blue | 3+ (300) |

| Blue | 4+ (>1000) |

From Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1153-1162.

Urine Microscopy

Red Blood Cells

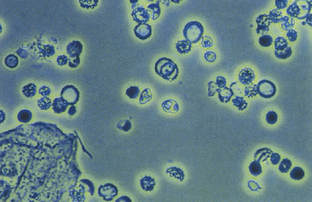

Urine specific gravity may affect findings, because red cells may lyse at values lower than 1.007 (Vaughan and Wyker, 1971). Normal-appearing red blood cells (RBCs) suggest a lesion in the urinary tract, whereas dysmorphic RBCs are probably of glomerular origin (Fig. 40-1). Red cell casts are typically found at the edges of the glass coverslip and are highly suspicious for renal parenchymal disease.

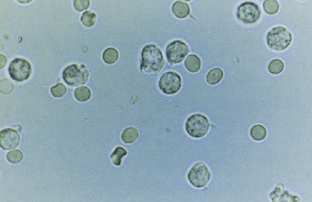

White Blood Cells

Normal urine samples may show some white blood cells (WBCs) on high-power examination (Fig. 40-2). For women, fewer than 5 WBCs/hpf is normal, and for men fewer than 2 WBCs/hpf is normal (Simerville et al., 2005). Values in excess of these limits constitute microscopic pyuria. Purulent, cloudy urine with WBCs too numerous to count describes gross pyuria.

Figure 40-2 Urinalysis: white blood cells.

(From Gerber GS, Brendler CB. Evaluation of the urologic patient. In Wein AJ [ed]. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th ed, vol 1. Philadelphia, Saunders-Elsevier, 2007, p 107.)

Casts

RBC casts signify a nephritic or vasculitic process. WBC casts are often considered pathognomonic for pyelonephritis, but may be found in other types of nephritis. Granular and waxy casts signify renal parenchymal disease. Hyaline casts may be normal in concentrated specimens or a marker of renal infection or disease.

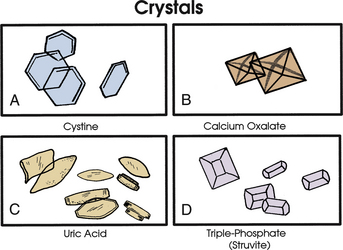

Crystals

Various crystal morphologies may be seen in urine samples (Fig. 40-3).

Other Diagnostic Tests

Endoscopy

Urinary endoscopy (cystoscopy) provides visual diagnosis and the opportunity for intervention. Rigid or flexible endoscopic procedures are available. Common interventional techniques include stone retrieval, stent placement, tumor biopsy and resection, and laser treatment. Risks include infection, bleeding, urethral damage, and bladder perforation.

Imaging Studies

Common Urinary Tract Concerns

Dysuria

Dysuria significantly increases the chance that a patient has a UTI. However, there are many potential causes of dysuria (Box 40-1), and empiric treatment based on this symptom alone leads to unnecessary antibiotic use. Incorporating other symptoms increases the likelihood that a UTI is the cause (see Urinary Tract Infection) (Bent et al., 2002; McIsaac et al., 2002).

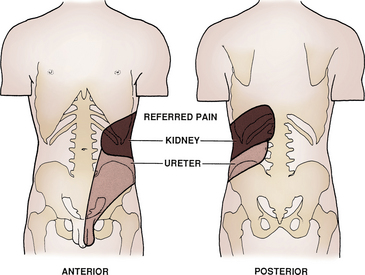

Flank Pain

Flank pain may be a presenting complaint indicating urinary tract disorder. It is typically not relieved by position changes and is colicky in nature. Nausea and vomiting may coincide. Obstruction (e.g., kidney stones) and inflammation (e.g., pyelonephritis) are the two most common causes. The location may help localize the underlying cause (Fig. 40-4). Tumors are less likely, because they are usually only symptomatic if they distend the renal capsule or obstruct the ureter.

Urinary Frequency

Adults typically urinate five to six times a day (Gerber and Brendler, 2007). Frequency usually represents an increased number of episodes with small volumes of urine as opposed to increased urine volumes, such as in polyuria. These factors help narrow the differential diagnosis (Box 40-2).

Hematuria

Hematuria in Adults

Gross Hematuria

Confirmation of blood in the urine with dipstick and microscopy is needed in cases of red-tinted urine, because certain substances can discolor the urine (see Table 40-1). However, visible clots are unlikely to have a mimic. History should focus on signs and symptoms of infection, trauma, as well as risk factors for urinary tract malignancy (see Bladder Cancer). Physical examination should assess the external genitalia and include a pelvic examination in women and a prostate examination in men. Urology consultation is appropriate, except when an obviously benign (e.g., menses) or treatable cause is found. Even when a treatable cause is identified (e.g., renal calculi), close follow-up with repeat urinalysis is needed because gross hematuria is frequently a harbinger of serious urinary tract pathology (Khadra et al., 2000).

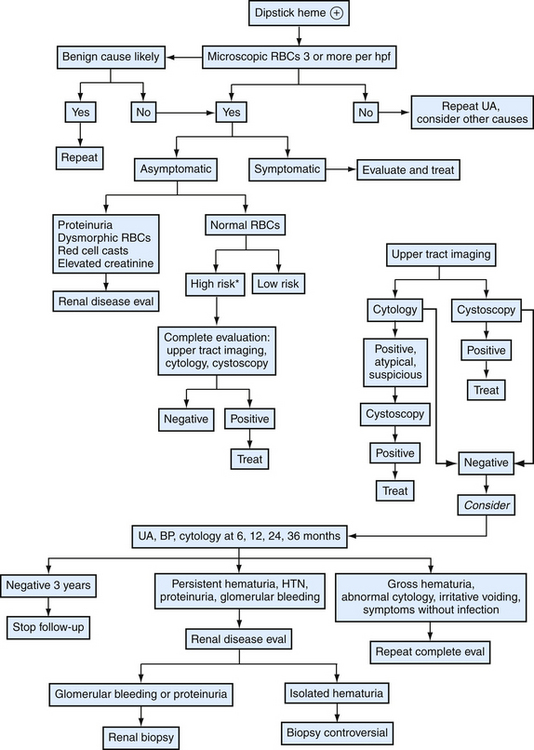

Microscopic Hematuria

Because routine screening is unhelpful, family physicians encountering microhematuria should consider patient risk characteristics and systematic laboratory testing and imaging (Fig. 40-5). The first step in approaching asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is to verify it is a consistent finding. Patients should have repeat urinalysis, and if two separate follow-up samples are normal, no further evaluation is needed. Transient hematuria is not unusual, and serious urinary tract pathology is unlikely in patients younger than 40 years. Furthermore, history or examination may reveal a benign cause—menses, sexual activity, vigorous exercise, viral illness, or trauma. If repeat examination is normal after these considerations, no further examination is needed. A caveat would be the patient at risk for bladder cancer, because intermittent hematuria can precede this finding, and more extensive follow-up may be warranted (Grossfeld et al., 2001b). Family physicians should be cautious not to misattribute certain causes as benign. For example, warfarin (Coumadin) may cause hematuria if the patient is excessively anticoagulated, but it should not cause hematuria within its goal international normalized ratio (INR) range. Hematuria in this setting is often a sign of urologic disease (Culclasure et al., 1994).

A cause for hematuria is often not found even after a complete evaluation. Isolated hematuria is asymptomatic microscopic hematuria with a normal urologic evaluation and no signs of systemic disease or microscopic evidence of intrinsic renal disease (the definition slightly differs for children). The prognosis is good, although some studies indicate a high proportion of renal abnormalities (e.g., IgA nephropathy). Thus, surveillance for signs of renal disease is appropriate (Grossfeld et al., 2001b). Also, up to 3% of patients with initially negative workups are later found to have a urinary tract malignancy. High-risk patients should have periodic follow-up with focused history, blood pressure, urinalysis, and urine cytology for up to 3 years. This regimen can also be considered for low-risk patients (see Fig. 40-5). Evaluation and treatment of symptomatic microscopic hematuria is directed at the condition. However, family physicians should consider the underlying risk of urinary tract abnormalities when deciding on follow-up. For example, a patient with a symptomatic kidney stone may have microhematuria. Although this provides the most likely explanation for the bleeding, if the patient has a background risk for malignancy (e.g., smoking) or renal disease, repeat urinalysis is needed to ensure resolution.

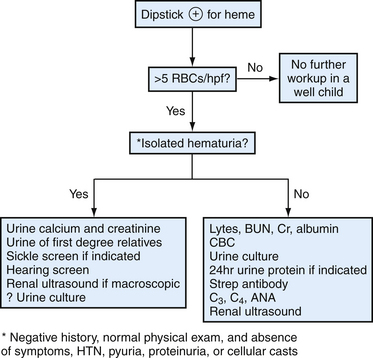

Hematuria in Children and Adolescents

Hematuria is a relatively common finding in children, with an estimated prevalence of 0.5% to 2% of asymptomatic school-age children (Dodge et al., 1976). Those with hematuria and proteinuria, particularly when associated with hypertension, edema, or urinary casts, need aggressive evaluation for underlying glomerular disease or uropathy. The vast majority of children with hematuria, however, present with isolated hematuria. This is typically detected on a random urine sample obtained in the context of a routine physical examination but may also present as asymptomatic gross hematuria. In children, the term isolated refers to the complete absence of symptoms, significant past medical or family history, physical examination findings, or other abnormalities on urinalysis. This distinction often separates those children with benign processes from those with underlying pathology.

Once the diagnosis of hematuria has been confirmed and a complete history obtained and physical examination performed, a staged evaluation should ensue (Fig. 40-6). Significant underlying renal or urologic disease is highly unlikely in children with isolated microscopic hematuria (Bergstein et al., 2005). A more thorough evaluation is indicated for asymptomatic macroscopic hematuria.

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are the symptoms traditionally associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Many subcategories of LUTS exist, but the two most prominent are storage and voiding symptoms (Box 40-3). Voiding symptoms imply obstruction, but physical obstruction may not be responsible. In men with BPH, for example, detrusor overactivity, neurologic disorders, or age-related smooth muscle dysfunction may be the cause. Thus, LUTS should shift attention toward a larger symptom complex with many potential causes. This is particularly important when dealing with urinary tract disorders such as BPH, incontinence, and overactive bladder.

Nocturia

Nocturia describes waking at night to urinate. It is more common in older adults, but no population data define a normal range for any group; therefore the complaint implies a deviation from a perceived norm. Furthermore, the primary complaint often centers on the sleep disturbance rather than on urination. It may represent frequent nocturnal urination or excessive nocturnal urine production (nocturnal polyuria). Although often thought of as a prostatic symptom, it is common in both men and women. The many secondary causes in addition to local causes include prostatic hyperplasia and bladder dysfunction (Box 40-4). In patients with prominent lower urinary tract symptoms, the problem is compounded by urination difficulty. Furthermore, studies in older adults indicate that nocturia/LUTS increases risk of falling (Parsons, et al., 2009). Age-related variations in arginine vasopressin secretion may play a role in nocturnal polyuria (Weiss and Blaivas, 2000).

Treatment centers on the underlying cause, and a voiding diary may aid clinical decisions. Prostate hyperplasia or bladder dysfunction often receives first attention. Treating BPH may help, although BPH often does not result in true physical obstruction, and epidemiologic data have indicated that nocturia is common in men without prostatic obstruction. Thus, family physicians should consider the contribution of nocturnal polyuria. For example, patients with chronic heart failure and leg edema may benefit from fluid restriction and napping with leg elevation during the day. Treating obstructive sleep apnea helps alleviate the increased urine production resulting from increased atrial natriuretic peptide production. Behavioral interventions include avoiding excess nighttime alcohol or fluid intake and afternoon napping. Adjusting diuretic doses so they are given earlier in the evening should negate medication effects during sleep (Weiss and Blaivas, 2000).

Proteinuria

The urine dipstick is the most convenient measurement, but a more accurate test is the Upr/UCr ratio, obtained by dividing the random urine sample protein level by the urine creatinine level (both in mg/dL). This ratio has proven correlation with 24-hour excretion rates (Ginsberg et al., 1983). Thus, random urine samples are the best way to identify and follow proteinuria, and 24-hour collections are usually not needed (Levey et al., 2003) (Table 40-3). However, results from those with low or high levels of muscle mass may not correlate as well with 24-hour measurements (Venkat, 2004).

| Test | Protein Value |

|---|---|

| Dipstick | |

| UPr/UCr∗ | |

| 24-hour urine assay |

∗ Urine protein/creatinine ratio.

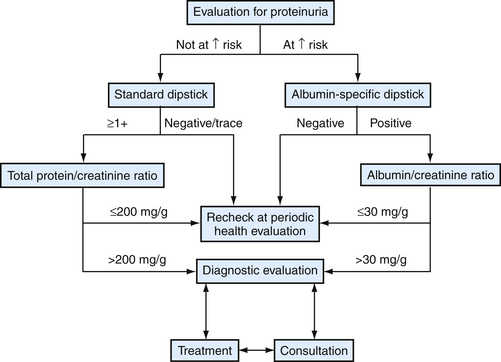

Proteinuria in Adults

Adults with proteinuria need their UPr/Ucr determined. Those with values outside the normal range should undergo an evaluation for CKD (see later). Patients with dipstick proteinuria but normal-range UPr/UCr values should be rechecked at periodic follow-up (Fig. 40-7).

Figure 40-7 Approach to proteinuria in adults.

(Modified from Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:137-147, E148-E149. Redrawn from National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Quality Initiative. See Web Resources.)

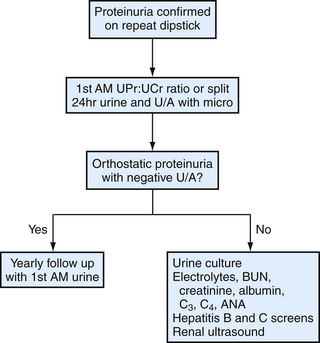

Proteinuria in Children and Adolescents

Pathologic proteinuria, whether isolated or symptomatic, occurs in the setting of a variety of glomerular and tubulointerstitial diseases (Box 40-5). Some children may present with the nephrotic syndrome (proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, edema). Depending on the degree of proteinuria and the results of the initial laboratory evaluation, a renal biopsy may be indicated (Fig. 40-8).

Anatomic Disorders

Anatomic urinary tract disorders involve various congenital and acquired abnormalities, most notably of the external genitalia. Testicular disorders are seen more often than abnormalities of the penis, particularly undescended testes. Anatomic derangements of the bladder, ureter, and kidney are often only discovered incidentally or during an evaluation for UTIs, voiding problems, CKD, or pain possibly related to the urinary tract. For example, posterior urethral valves cause vesicoureteral reflux and may contribute to recurrent UTIs (see Urinary Tract Infections in Children).

Scrotal masses are frequently encountered in family medicine. Anatomic causes of scrotal masses are not limited to the urinary tract, and neoplastic and infectious causes are also in the differential diagnosis (Table 40-4). Scrotal or testicular pain, the so-called acute scrotum, implies a more urgent or emergent cause (e.g., testicular torsion). Because the history and physical examination may not be adequate to differentiate certain conditions (e.g., epididymo-orchitis from testicular torsion), adjunctive imaging such as ultrasound is often used.

Table 40-4 Selected Differential Diagnosis of Scrotal Masses with Physical Findings

| Abnormality | Physical Finding |

|---|---|

| Epididymitis, orchitis | Tender mass |

| Hydrocele | Transilluminates |

| Inguinal hernia | Does not transilluminate |

| Testicular torsion | Pain and loss of cremasteric reflex |

| Torsion of the appendix testis | Blue dot sign |

| Trauma | Tender scrotum, edema, trauma history |

| Tumor | Solid mass |

| Spermatocele | Nontender cystic mass |

| Varicocele | Bag of worms appearance |

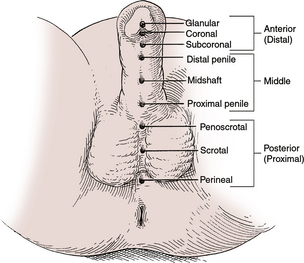

Hypospadias

Hypospadias, in which the urethra opens on the underside of the penis, is infrequently seen (Fig. 40-9). However, it is important that hypospadias is recognized early, preferably at the initial newborn examination. It can occur with or without chordee (curvature). Circumcision should be withheld and a urology consultation obtained. Hypospadias must be differentiated from ambiguous genitalia, which implies an intersex disorder. Epispadias, in which the meatus is located on the dorsal surface of the penis, is uncommon and is usually associated with extrophy of the bladder.

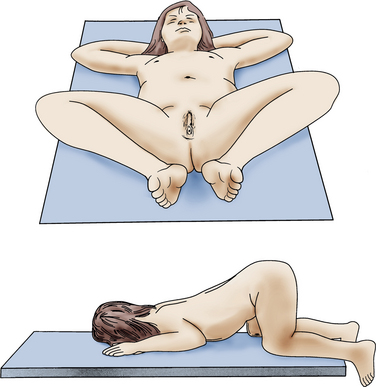

Labial Adhesions

Labial adhesions may be seen in young girls and may be partial or complete (fusion) and asymptomatic. However, labial adhesions can be associated with difficult or abnormal urination and may contribute to the development of UTIs. It is important to perform an external genital examination in the female with her first UTI (Fig. 40-10). Retrospective data and case series support topical estrogen cream to the affected areas, with gentle traction until the adhesions have separated (Bacon, 2002). In a recent study, however, labial separation occurred more quickly and with less recurrence in patients treated with betamethasone than in those treated with estrogen cream (Mayoglou et al., 2009).

Phimosis and Paraphimosis

Phimosis (inability to retract foreskin over glans) and paraphimosis (inability to return retracted foreskin over glans) are possible complications seen in the uncircumcised male (Fig. 40-11). About 50% of boys typically are able to retract their foreskin by 1 year of age and 80% by age 3 (Anderson and Anderson, 1999). Topical estrogen therapy has been reported as successful, but no randomized trials support its use (Yanagisawa et al., 2000). However, low-potency topical corticosteroid therapy combined with daily prepuce retraction appears effective for phimosis (Zampieri et al., 2005).

Figure 40-11 Paraphimosis.

(From Kleigman R, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, ed 18. Philadelphia, Saunders-Elsevier, 2007, p 2256.)

Testicular Disorders

Testicular Torsion

Although occasionally seen in the newborn male, testicular torsion is an acquired condition seen during puberty and is an emergency. It usually presents with abrupt onset of severe scrotal pain, at times waking the patient up in the early morning. Associated signs and symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Intermittent testicular torsion has been described. On physical examination, the testis may lie in a more horizontal position, caused by a lack of normal attachment to the tunica vaginalis (“bell clapper” deformity), and demonstrate a loss of the cremasteric reflex. The diagnosis of testicular torsion can be made by physical examination or with the assistance of color Doppler ultrasound; however, physical examination is unreliable for ruling torsion in or out (Schmitz and Safranek, 2009). Timeliness of the diagnosis is critical, because testicular viability declines to 0% if detorsion occurs 24 hours after the onset of symptoms (Brenner and Ojo, 2004). Testicular torsion can occur in systemic illnesses, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, or can mimic the symptoms of other conditions, such as appendicitis or nephrolithiasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree