Chapter 46 Difficult Patients

Personality Disorders and Somatoform Complaints

Our treatment of patients with “unexplained physical symptoms,” as with personality styles, also follows this spectrum or dimensional approach. In it mildest form, unexplained physical complaints will present in generally normal, healthy patients. These benign physical complaints are often accompanied by psychological issues just as often as psychological symptoms are accompanied by physical complaints. Features of psychological problems just as psychological symptoms always accompany physical problems (Kroenke et al., 1994). Moreover, symptoms of both a physical and a psychological nature frequently appear in patients—indeed, in all people—without obvious explanation. Mild physical symptoms such as “butterflies” in the epigastrium just before a public speech may disappear as mysteriously as they appear and are of no consequence. At the other end of the spectrum are increasingly severe, persistent, or disabling, unexplained physical symptoms that eventually cross a threshold and become a disorder in their own right. The somatoform disorders are this family of full-blown diagnostic conditions, characterized by disabling physical symptoms with no physical explanation.

Classification

Personality Disorders

The preliminary diagnosis of a personality disorder begins by identifying the appropriate cluster or dimension, because it is easiest to recognize the broad traits of a cluster diagnosis first. The three clusters of personality disorders are cluster A, odd and eccentric; cluster B, dramatic, emotional, or erratic; and cluster C, anxious or fearful. These clusters or dimensions are subdivided into specific personality subtypes with general characteristics (Box 46-1). Because personalities are complicated, it is not unusual for a patient to meet the criteria for two cluster diagnoses and more than one specific personality disorder diagnosis.

Box 46-1 Personality Disorder Clusters∗

From American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC, APA, 2000.

Cluster B (Dramatic, Emotional)

Cluster C (Anxious, Fearful)

Unexplained Physical Symptoms vs. Somatoform Disorders

Physical symptoms appear and disappear on a regular basis in normal people. Less than 3% of these symptoms result in a visit to a physician (Banks et al., 1975), but more than half the visits to primary care physicians are for symptoms. Even symptoms severe enough to trigger a visit are usually self-limited; about three-quarters improve or disappear in 2 weeks, and over half of those remaining have improved or disappeared at 3 months (Kroenke and Jackson, 1998). Most patients do not remember having a symptom that they reported 1 year earlier (Simon and Guerje, 1999). From this cohort of symptomatic patients, a substantial number have symptoms sufficiently persistent, severe, or numerous to justify a diagnostic workup, which usually reveals a medical problem that the family physician manages in the usual way, as described throughout this text. In about one third of patients, however, the symptoms are causing impairment and no physical explanation can be found; alternatively the symptom is out of proportion to the supposed explanatory finding; these patients are somatic. At the more severe end of the continuum, somatic symptoms cluster into discrete diagnostic categories: the somatoform disorders, including somatization disorder, conversion disorder, somatoform pain disorder, hypochondriasis, factitious disorder, malingering, and body dysmorphic disorder. Primary care physicians tend not to pursue diagnoses to the level of these categories, because it is a time-consuming process not yet shown to improve patient outcomes. However, these categories have promising implications for managing the difficult clinical relationship, particularly in the context of personality types and disorders.

Unexplained physical symptoms are often benign and transitory, and only 3% of patients with these symptoms see a physician. Somatic complaints are described by patients within all domains of the traditional review of symptoms. Somatoform disorders are a group of severe psychiatric conditions that present with physical symptoms that suggest a medical condition but that cannot be adequately explained by a medical condition. Patients can have both a medical condition and unexplained physical symptoms that meet criteria for a somatoform condition. Box 46-2 describes somatoform disorders (DSM-IV-TR classification). Social or occupational impairment in these patients exceeds what would be expected based on physical complaints.

Box 46-2 Somatoform Disorders

Comorbidity of Personality and Somatoform Disorders

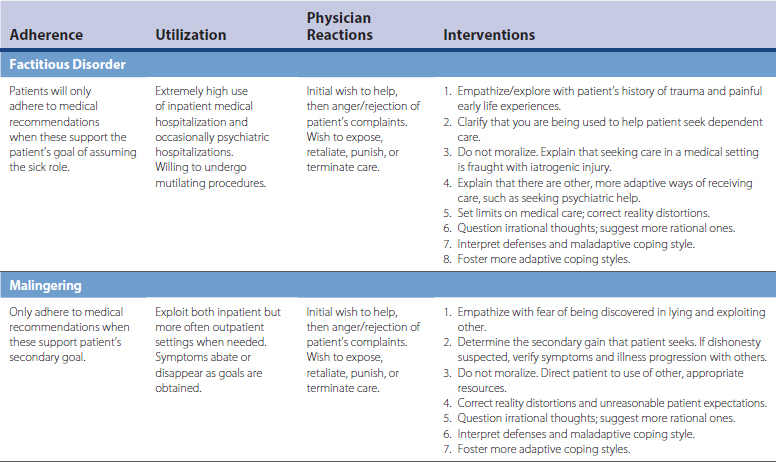

Significant comorbidity also exists between other somatoform disorders and other personality disorders. For example, patients with hypochondriasis and body dysmorphic disorders are obsessed with fear of illness and fear of a body defect, respectively. Patients with both of these also display compulsive requests for medical care. Clinically, these disorders have overlapping features with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and may be variants of OCD. Interestingly, all three of these disorders can be managed similarly and are somewhat responsive to treatment with antidepressants. Conversion disorders also have a long-standing connection to hysteria and more recently to Briquet’s syndrome (somatization disorder) and can be understood and managed similarly to the histrionic personality disorder. Also, reports of somatic symptoms in patients with factitious and malingering disorder may represent a form of antisocial personality disorder. All three of these disorders have in common a conscious desire to lie and mislead others for secondary gain.

Management

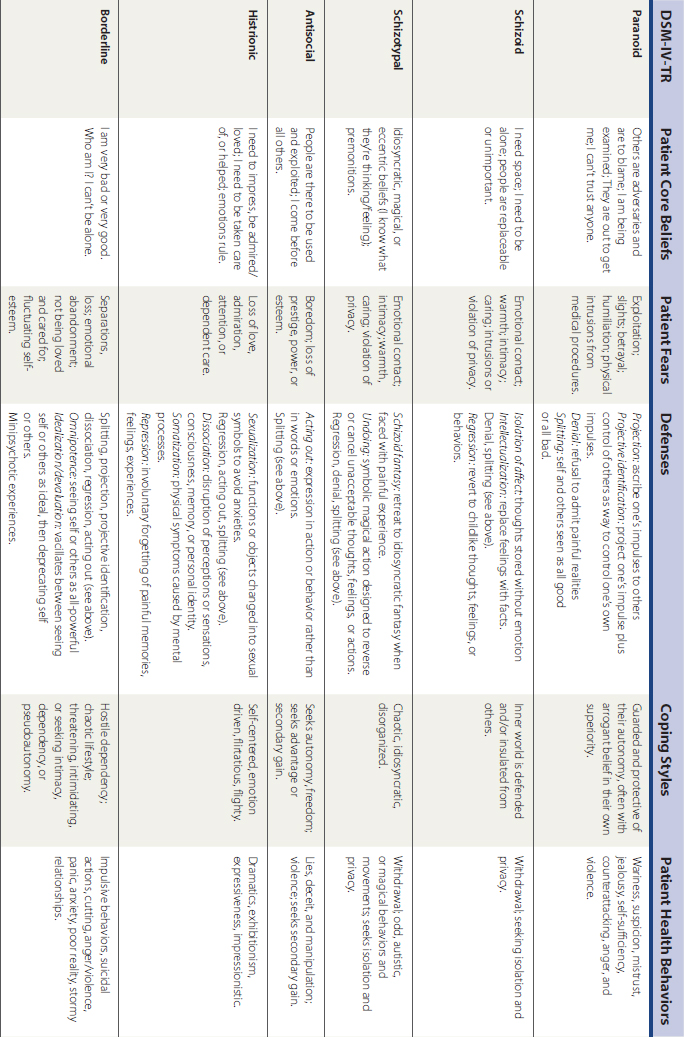

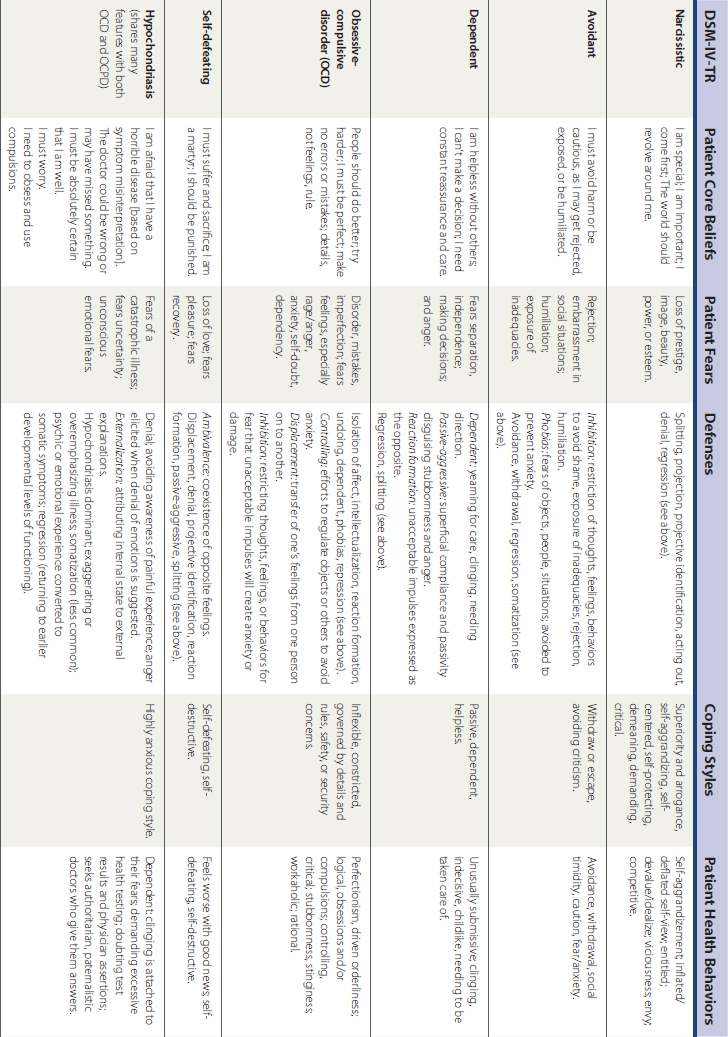

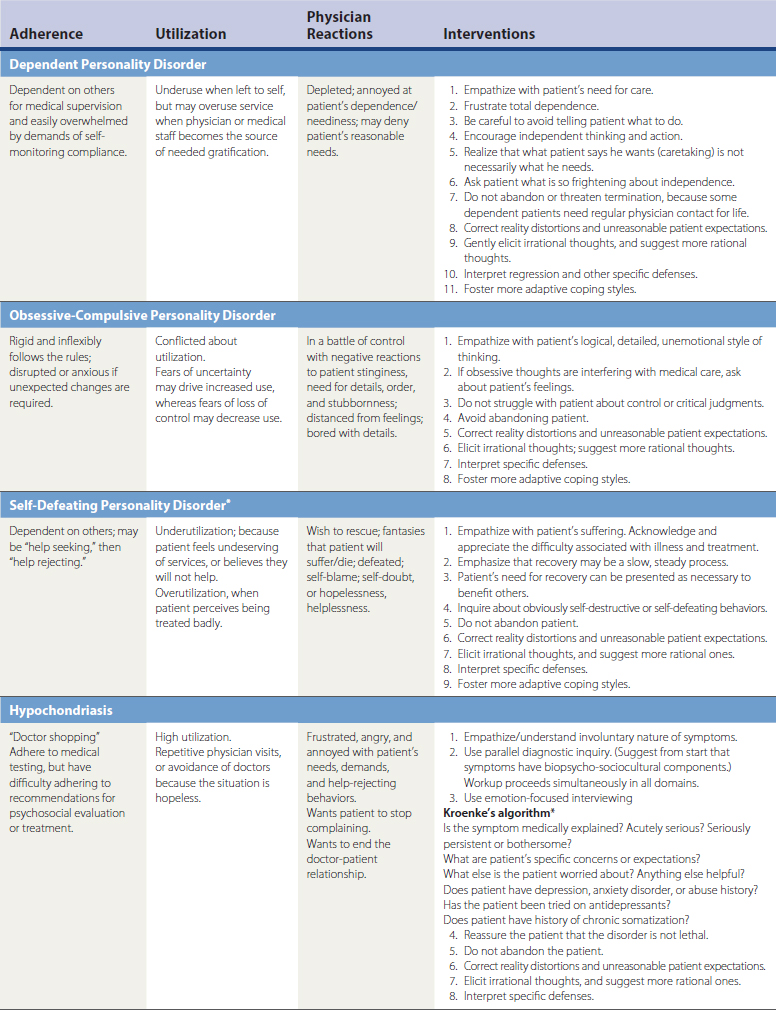

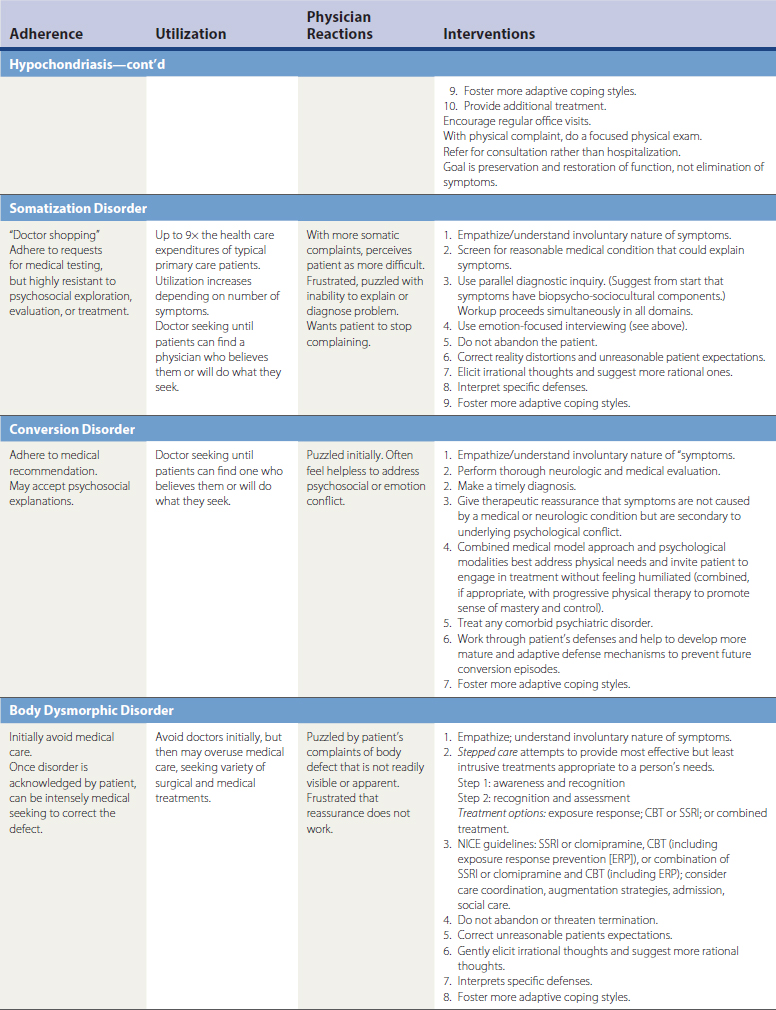

To create therapeutic relationships with patients who might otherwise be experienced as difficult, the clinician must first understand patients’ core beliefs, thoughts, and fears; then understand their defenses and coping styles; and finally, understand the health-related behaviors that follow from these beliefs and styles. This understanding helps physicians utilize the reactions such behaviors evoke in them, thereby leading to alternative responses and potential interventions. Tables 46-1 and 46-2 outline this process using DSM-IV-TR classification.

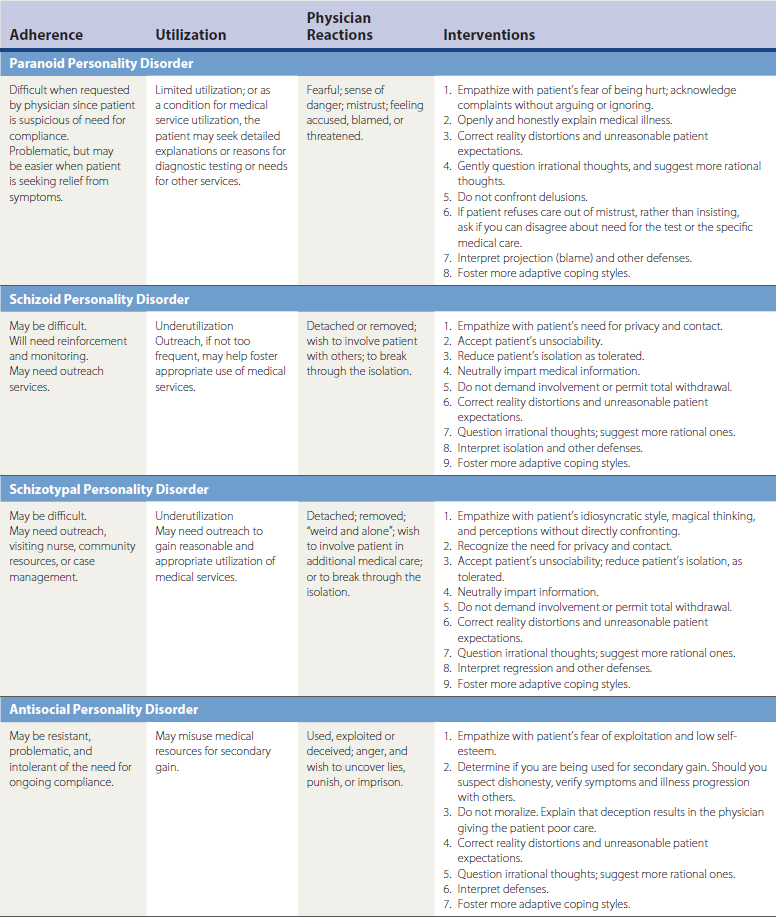

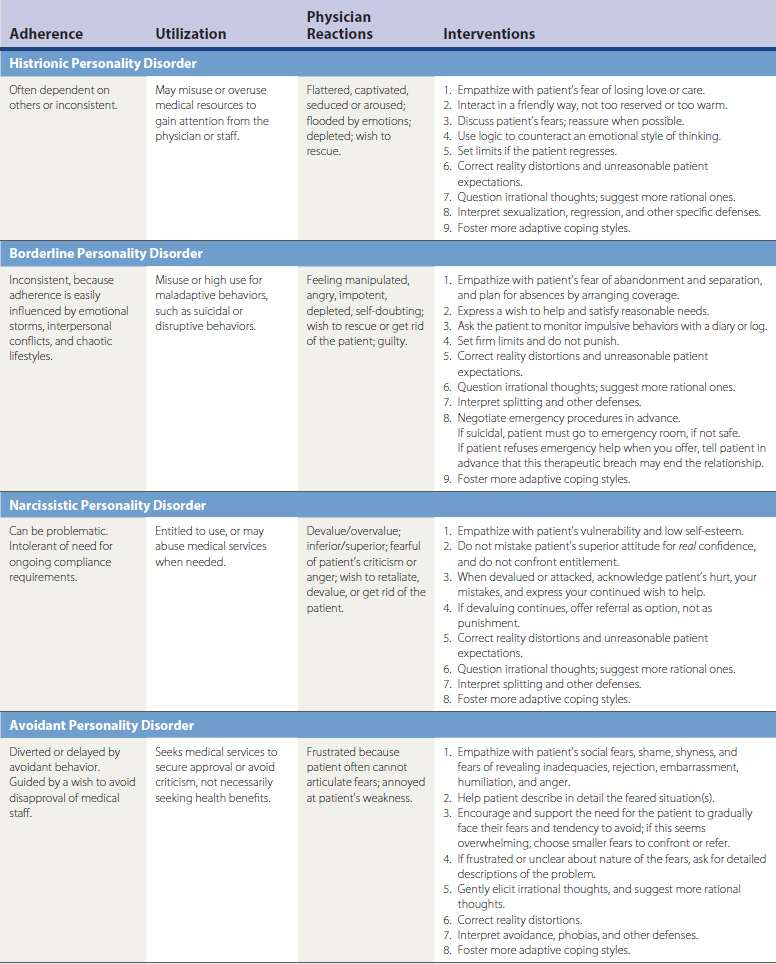

Table 46-2 Difficult Patients: Adherence, Utilization, Physician Reactions, and Interventions (DSM-IV-TR)

Patient Core Beliefs, Irrational Thoughts, and Fears

The CBT sequence of stress, acting on core beliefs and irrational fears, and subsequent development of symptoms or maladaptive behaviors is described for difficult patients in Table 46-1. Adherence to medical recommendations and use of medical services are somewhat predictable based on the particular personality or somatoform disorder.

Defenses and Coping Styles

Patients with severe unexplained somatic symptoms tend to use denial, externalization, and somatization, converting psychosocial distress and problematic interpersonal relationships into unexplained physical complaints. Patients with severe unexplained somatic symptoms tend to use high/low anxious coping or manipulative coping styles (see Table 46-1).

By understanding the constellation of defenses and coping styles used by difficult patients, the physician may be able to modify the pathologic defense or coping style that is interfering with the patient-physician alliance and the delivery of medical care. A physician can use clarification, confrontation, and interpretation (see Table 46-1). For example, a borderline patient may feel hurt and abandoned by the physician’s vacation and accuse the physician of not caring. This patient may use a defense mechanism called devaluation (physician is deprecated as uncaring) and a coping style of manipulation (threatens suicide). With this understanding, the physician can begin to help the patient by not taking the patient’s efforts to devalue or manipulate personally. The physician can respond to the patient by empathizing with the patient’s fears of abandonment. The physician may clarify that the patient has a distorted belief, and that the vacation is being incorrectly experienced as a personal abandonment of the patient. The physician may further clarify that the vacation does not communicate anything about the physician’s future ability or wish to care for the patient. The patient can be reassured of the physician’s return, future realistic medical availability, specific limits of availability, and medical coverage by another physician. In a preventive effort to allay a crisis and help a borderline patient manage separation fears, the physician (before the vacation) could suggest a new coping style of having the patient schedule a meeting with a medical colleague who will provide coverage while the physician is away. Often, it is helpful to anticipate issues that may arise for the patient and suggest specific problem solving and coping.

Patient Behaviors, Adherence, and Use of Medical Services

Difficult patients often display characteristic behaviors that affect their adherence to medical recommendations and use of medical services. Understanding these behaviors can also help physicians manage their expectations of these difficult patients and improve the chances for effective interventions that might improve medical adherence and health outcomes. In general, patients with cluster A personality disorders (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal) tend not to adhere to medical recommendations and underuse medical services. They may require outreach to involve them in their own medical care. Cluster B patients (antisocial, histrionic, borderline, narcissistic, and self-defeating) tend to have variable adherence to medical recommendations and may misuse, overuse, or underuse medical care. Cluster C patients (dependent, obsessive-compulsive, avoidant) tend to adhere to medical recommendations because of fear of the consequences of nonadherence. They are ambivalent users of the medical system and tend to use medical services appropriately when others are involved in their care.

Physician Reactions to Difficult Patients

Atypical Behaviors

Common atypical physician behaviors may include ordering tests to placate a patient, asking for more than the usual number of consults on a patient whose case does not seem medically complicated, suggesting increasingly aggressive diagnostic testing or procedures when the yield of these tests is likely to be low, repeatedly extending the time spent with a particular patient or family, lowering the customary fee, offering free treatment, or developing a personal (not professional) relationship with a patient. Common physician reactions associated with difficult patients are reviewed in Table 46-2.