The Overhead Athlete—Challenges and Decision-Making

Richard J. hawkins

Sumant G. Krishnan

INTRODUCTION

From an orthopedic and therapy point of view, it has been some time since we have had an updated book on the overhead athlete’s shoulder. The changes in the past 10 years have been significant in this arena. Our understanding of the rehabilitation and injury prevention aspect of shoulder problems in the overhead athlete has dramatically improved. Biomechanical studies and a better understanding of the many processes that occur have contributed to better understanding of the function of the athlete’s shoulder. Better appreciation of SLAP (superior labrum anteriorto-posterior) lesions, internal impingement, the relationship between excess translation and instability, and cuff pathology have advanced over the past decade. Ten years ago, we knew little about SLAP lesions and internal impingement and, therefore, had limited understanding of how to treat them. With the development of arthroscopic surgery, we can now fix SLAP lesions, debride internal impingement lesions, and address excess translation effects by applying suturing or radiofrequency heat.

From a surgical and rehabilitative perspective, there are several factors to consider in determining how the overhead athlete’s shoulder may differ from that of the average patient. For example, what is the definition of an athlete? Obviously, Roger Clemens qualifies, but what about the rest of us? Many of us like to consider ourselves athletes and perhaps we are such, functioning at very different levels and within a varied group of endeavors. Regardless of the definition of an athlete, when we consider the athlete’s shoulder and how it differs, we need to analyze it from different viewpoints.

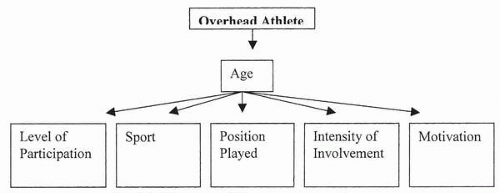

These viewpoints relate to the level of participation, the sport and position played, the intensity of involvement, the motivation, and the age of the athlete (Fig. 1-1). For these athletes, we need to consider whether they are recreational, amateurs, or professionals. There are financial implications at the professional level. Once athletes are properly identified according to participation level and type of activity, we then need to consider whether they are unique in their diagnoses and pathologies and whether their treatment, therefore, should vary from that of the normal population. This is likely the case. When analyzing the outcome of treatment for an athlete, should the measurements be tailored to the patient’s athletic profile?

Levels of participation progress through competition at youth, recreational, high school, college, professional, and international levels. All sports could be related to the athlete’s shoulder, but the sports that cause shoulder problems in particular relate to the overhead nature of such sports as baseball, tennis, swimming, volleyball, and javelin throwing. Other sports such as football, soccer, and basketball may also be related to shoulder injury, but in the first group of sports, the injury is likely overuse-related, whereas in the second group, the injury is likely traumatic. For example, a baseball pitcher who throws many pitches in a game may have tendinosis, whereas an outfielder who falls on an outstretched arm may have a dislocated shoulder.

Athletes have a strong desire to participate. The higher the level at which an athlete participates, frequently the higher the motivation and the greater the desire for normalcy. This influences the need for early and appropriate diagnosis and aggressive treatment programs along with

appropriate injury prevention programs. Athletes may be disabled by problems that may not affect the average sedentary individual. Frequently, the higher the demand for participation in these athletes, the greater the potential for injury. Many professional baseball pitchers find themselves on the injury disabled list because of shoulder problems.

appropriate injury prevention programs. Athletes may be disabled by problems that may not affect the average sedentary individual. Frequently, the higher the demand for participation in these athletes, the greater the potential for injury. Many professional baseball pitchers find themselves on the injury disabled list because of shoulder problems.

FIGURE 1-1. Analysis of shoulder problems in the overhead athlete first involves an assessment of the various reasons that the athlete’s shoulder differs from that of the general population. |

It is unusual to see problems in very young children who participate in athletic endeavors, even those who pitch a lot of baseballs. Progressing through the years, athletes develop problems with overuse and tendinosis and may end up as a masters athlete in the older age group with a completethickness rotator cuff tear, which is unheard of in youth.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPLICATIONS

Problems and diagnoses in the athlete’s shoulder may differ from those in the general population. At the same time, athletes may have exactly the same problem as occurs in the general population, particularly when trauma is involved. If a patient, whether an athlete or not, is involved in a motor vehicle accident, he or she may sustain an acute dislocation of the shoulder. This injury can also occur in the football lineman who tackles someone. It is important, particularly in the overuse situation, to keep in mind that athletes do have different problems and different diagnoses. For example, the professional baseball pitcher who presents with shoulder pain often demonstrates excess anterior translation and internal impingement. Conversely, the 45-year-old nonathlete workman who presents with shoulder pain almost never has a diagnosis of anterior shoulder instability. It is much more common for this patient to have impingement degenerative cuff disease. Volleyball players are frequently subject to suprascapular nerve problems. Hockey players commonly get their shoulders jammed into the boards, resulting in acromioclavicular dislocations. Consequently, diagnoses may vary, depending on the sport and other features. In overhead athletes, it is important to keep in mind the implications of an acute injury versus a chronic overuse situation.

Diagnosing the Problem

Depending on the level of participation and time of season, among other factors, diagnosis may need to be established “yesterday.” In some circumstances, there is time enough for “Mother Nature” to take her course, allowing the diagnosis to evolve and become clear on its own. At the professional level, however, we are quick to establish a diagnosis, exposing the athlete immediately to x-ray studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and whatever else is needed to aid in establishing the diagnosis, so that appropriate, effective, and efficient treatment can be instituted quickly. At the Little League level, however, we often allow some time for these diagnoses to become evident. In the Little Leaguer, the approach is less aggressive with regard to using diagnostic testing toward establishing an immediate diagnosis, so as to avoid compromising the health of the patient.

Clinical Examination

After a fracture, acromioclavicular dislocation, or acute dislocation of the glenohumeral joint, the clinical examination is fairly straightforward. Patients present with a painful shoulder with limited range of motion. In many overhead athletes who present with shoulder pain due to overuse, the physical findings vary, but frequently consist of limitation of internal rotation and crossed-arm adduction, scapular dysfunction, weakness in certain ranges (e.g., external rotation), and instability findings (e.g., excess translation, positive relocation testing, and often signs of impingement). Many overhead athletes, such as throwers, have excess external rotation. This constellation of physical examination signs is frequently found in the high-profile overhead athlete, such as the professional baseball pitcher, but it is rarely found in the general population (1).

Instability and Translation

In the overhead athlete’s shoulder, it is critical to understand the relationship between translational measurements and instability. Instability is a loss of control of the ball in the socket that produces symptoms. These symptoms are usually of “looseness” or “coming out” and those described as instability-related. The difficulty occurs when pain is the only symptom occurring in a shoulder that has excess translation, which may or may not be interpreted as translation or be labeled as “instability.” It is common for overhead athletes to have excess translation, and recent appreciation of different pathologies such as internal impingement and SLAP lesions may bear some relationship to this excess translation. These patients may have no symptoms or signs of instability other than this excess translation, complicating the diagnosis. Many patients have considerable physiologic translation of the ball in the socket and yet have no symptoms of instability. It remains unknown whether excess translation can create a tendinosis problem through stretching of the joint capsule and tendons, or whether excess work of these same structures will cause pain. When performing translational testing on patients who complain of instability, particularly when they are awake, it is important to ask them if the testing reproduces the instability complex by reinforcing the symptoms and direction of displacement of the unstable shoulder. In assessing for translation in a patient who has perceived instability, we translate the shoulder posteriorly and describe how far it goes. For example, it may just move up the face of the glenoid, it may perch on the glenoid rim, or it may go over the rim. We then go through the following sequence of questions with the patient:

Do you feel your shoulder go out and come back in with my testing?

Is that the sensation you feel when your shoulder comes out?

Does it go in that direction?

If these questions are all answered in the affirmative, the diagnosis, or at least partial diagnosis, of posterior instability would be established.

Recent literature suggests that throwers with excess translation may not function biomechanically at their maximum capacity. In the presence of a SLAP lesion or internal impingement, a stabilizing procedure may be performed, more to address the excess translation than to address the possibility of instability. This may directly address the goal of making the shoulder more sound biomechanically.

There is a fine line between diagnosing excess translation and instability, particularly in patients with pain. Under these circumstances, it may be conjecture, at best, to say these patients have instability. Research work, particularly by Harryman and Matsen, has shown that translation does not equal instability (2). Certain symptoms more clearly represent instability, such as when a patient complains of the “shoulder coming out,” “shoulder is loose” or there is “catching and clunking.” The shoulder can, in the face of excess translation particularly with reproduction of those symptoms, clearly represent instability. It is common in patients who have a tendency toward multidirectional or posterior instability to reflect equal translational findings in both shoulders. Yet one is symptomatic, and the other is not.

Physical Signs

Over the past 10 years, many new physical examination signs have been described that aid in the diagnosis of shoulder problems in the athlete (1). Many signs suggest a SLAP lesion (3). These include the active compression test or O’Brien’s test, the moving valgus test of O’Driscoll, Kibler’s anterior slide test, Andrews’ clunk test, and the biceps load test, among others. Bicipital signs are often present with SLAP lesions, as are impingement signs. These overlapping signs often make the accuracy of the tests unpredictable. Gerber described the lift-off test, demonstrating subscapularis insufficiency (4). Recent publications have demonstrated the belly-press test as indicative of upper subscapularis problems and the lift-off test as more indicative of lower or entire subscapularis insufficiency (5). These are just a few of the newer tests that have evolved and are described in later chapters.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree