34 THE ORGAN AND TISSUE DONOR

This chapter is designed to give the trauma nurse a basic understanding of organ and tissue donation and the significant role that the trauma nurse plays in the donation process. The crisis created by the critical shortage of organs available for transplant will only worsen as the number of people in need of transplantation increases. Trauma nurses and other members of the health care team are front-line patient advocates and are essential for the early referral of the potential donor.

THE CRITICAL SHORTAGE

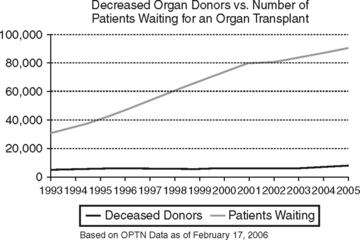

More than 93,000 people are currently waiting for a transplant in the United States.1 That number grows exponentially each year, and although the number of organ donors has increased, there continues to be a disparity between the availability of an organ for transplant and those in need of a transplant.1 On average, 118 people are added to the national organ transplant waiting list each day, one every 12 minutes. Approximately 18 patients die each day while waiting for a transplant because an organ did not become available in time.2 Tragically, fewer than one third of those patients waiting will receive the transplant they so desperately need (Figure 34-1).

FEDERAL REGULATIONS AND THE TIMELY REFERRAL OF POTENTIAL ORGAN DONORS

The critical shortage of organs for transplantation has prompted federal initiatives designed to increase professional and public awareness regarding the need for organs and tissues for donation. It is estimated that the annual number of potential brain-dead donors in the United States is between 10,500 and 13,800.3 In response the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) developed the “Medicare Conditions of Participation” regulations. These regulations require all U.S. hospitals to work collaboratively with their regional OPO and tissue recovery agency. Specifically, they charge every hospital with reporting all potential organ donors (and potential tissue donors) and inpatient deaths to the OPO. The regulations mandate that hospital staff be required to report every imminent death (including the potential for brain death) to the OPO in a timely manner. Hospital staff are required to make these referrals before life-limiting treatment decisions are made, including decisions to pursue “do not resuscitate” and “no pressors” options, before termination of life support, and before any discussion regarding organ and tissue donation is initiated with the family.4 Additionally, according to these regulations, the responsibility for conducting a discussion about organ donation with the family of a potential donor lies with the OPO staff or hospital staff trained by the OPO.4 These regulations are meant to relieve the hospital staff of the burden of determining donor suitability and to clarify when they should call in a referral. These regulations are not designed to exclude hospital staff from the consent discussion but to ensure that the OPC is included in the process.

Early referral to the regional OPO has many benefits for the staff, the patient’s family, and the recipients. Staff, who may be uncomfortable with discussing donation or who lack the knowledge to provide the option of donation to a family, are now relieved of that burden under the new regulations. Early involvement with the OPC will facilitate a collaborative discussion among all those involved to determine the most sensitive approach to the donation discussion at the most appropriate time. Potential donor families can be assured that the discussion regarding organ and tissue donation occurs at a time that is right for them, with the appropriate options shared on the basis of each situation. Families need time to have their questions answered. In instances where there is no donor designation, the family needs to be assured that their decision will be respected regardless of whether they choose to donate. The transplant recipient’s benefits are obvious. Lives are saved and many recipients enjoy the benefit of an improved quality of life through organ transplantation. Advances in the field of transplantation have allowed recipients greater survival times than ever before.1

Early OPC involvement can assist the staff in caring for the family and prevent well-meaning personnel from offering the option of donation in situations where it is inappropriate (if the deceased had human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] or metastatic disease) and from offering inaccurate information about the options for donation. As donor criteria continue to change, OPO staff are trained in the most current requirements and possesses the information necessary to screen a potential donor. The OPC can spend time with the family answering questions and reinforcing their options. This can be a time-consuming encounter and may require more information than the staff is able to provide.5 Ideally the trauma staff and OPC will collaboratively develop a plan and decide on the best approach to the family when consideration for organ donation becomes a reality.

DONOR PROFILE

The following scenario presents a donor profile that provides a “real life” clinical situation:

Concurrent solid organ injuries in the trauma patient may limit options for donation. Depending on the donor’s age and severity of the injury, some organs may be unsuitable for transplantation. Significant cardiac or lung contusions may or may not threaten organ viability. Depending on the location and severity, liver lacerations do not necessarily prevent a life-saving liver donation but may preclude splitting the liver for transplantation to two separate recipients. Blunt injury to the kidneys, pancreas, or intestines should be evaluated carefully to determine suitability for transplantation. Some injuries, for example a renal capsule tear, can be repaired and successful transplantation of that organ can still occur. The reality is that there are far too many people dying every day because a transplant did not become available in time, NOT to evaluate every donor, every organ, every time.6

It is essential for the trauma nurse to realize that trauma patients are not the only potential organ donors. In fact, from 1988 to 1996 the number of persons involved in motor vehicle crashes who become organ donors decreased 29%, whereas the number of patients who became organ donors as a result of a cerebrovascular accident, such as intracerebral hemorrhage or ischemic stroke, rose 57%.1 Any catastrophic cerebral insult, whether anoxic, hemorrhagic, ischemic, or traumatic, that results in uncontrolled cerebral edema can lead to brain death and the potential for organ donation. Some studies have shown that physicians and staff fail to recognize these patients as potential organ donors and subsequently fail to refer the patient to the OPO.7 In these cases the opportunity for organ donation is lost. The results of such missed opportunities are far reaching. In cases of donor designation, the donor’s choice to help others on his death is ignored. In the absence of such a designation, the potential donor family is denied their legal right to be offered the option of donation. When deprived of such an opportunity, to find solace while experiencing the loss of a loved one, they are further denied the comfort in knowing that their loved one’s final act of kindness, organ and tissue donation, could help countless others by saving and greatly enhancing the lives of others. Additionally, up to seven potential recipients that might otherwise receive a life-saving transplant may die before the next opportunity for a donor organ becomes available.

BRAIN DEATH

The Uniform Determination of Death Act of 1980, supported by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, confirmed the legality of and set parameters for the declaration of brain death. The act states that any individual sustaining irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function or irreversible cessation of all cerebral function, including the brainstem, is dead.8 Technologic advances make it possible to support multiple body systems so that the signs traditionally equated with life, cardiac and respiratory function, can be maintained despite the loss of all cerebral function and control.9 Therefore the organ donor is traditionally the individual who is brain dead or, more specifically, the patient who has died but remains on mechanical support for purposes of organ donation until organ recovery is completed. The non-heart-beating organ donor, also referred to as the donor after cardiac death, or the donor whose organs are recovered after asystole is discussed later in this chapter.

Once a primary insult occurs, whether medical or traumatic, the challenge to the health care team is to prevent secondary brain injury. In the absence of trauma, specifically skull fractures, in older children and adults the cranium is a closed vault. Within this rigid, closed cavity exists three elements: brain matter (80%), cerebrospinal fluid (10%), and blood (10%). The Monro-Kellie hypothesis states that when any one of these elements increases in volume, one of the other elements must accommodate that increased volume through a reciprocal reduction in volume.10 Failure to compensate results in uncontrolled increased intracranial pressure. Irrepressible intracranial hypertension causes a progressive decrease in cerebral perfusion as intracranial pressure exceeds mean arterial blood pressure. The resultant cerebral ischemia leads to brain death11 (Box 34-1).

BOX 34-1 Clinical Criteria for the Declaration of Brain Death

• Body temperature >95° F (35° C)

• No spontaneous movements in response to external stimuli

• No reflex activity except that elicited by spinal cord

From House-Park MA: Nursing care of the potential donor. In Chabalewski FL, editor: Donation and transplantation: nursing curriculum, pp. 105-130, Richmond, Va, 1996, UNOS.

The brain-dead individual exhibits no spontaneous respiratory effort, no response to painful stimuli, and absence of all brainstem reflexes (e.g., fixed, dilated pupils; absence of oculocephalic, oculovestibular, cough, gag, and corneal reflexes). Before declaration of brain death, all medical conditions or metabolic derangements that may affect the neurologic examination should be treated or corrected. Serum chemistries should be within normal limits, body temperature should be at or above 95° F (35° C), and there should be no drug levels that would impair neurologic reflexes, such as neuromuscular blockade, sedation, or anesthetics. The patient should be hemodynamically stable, with a systolic blood pressure equal to or higher than 90 mm Hg. It should be noted in cases where sedation has been used to decrease the brain’s metabolic requirements and in the presence of a significant serum drug level, a cerebral blood flow study can be used to confirm lack of cerebral blood flow, thus supporting the diagnosis of brain death.12

APNEA TESTING

Apnea is an essential component in the determination of brain death. Apnea testing is performed in the course of brain death examination. Before the test is initiated, the patient should be normothermic and normotensive with a systolic blood pressure 90 mm Hg or higher and a baseline Paco2 between 35 and 45 torr. The patient should not have received any drugs that could potentially suppress respiratory effort.12

Once these prerequisites are met, the patient is hyperoxygenated with 100% oxygen for at least 10 minutes. The patient is then removed from ventilatory support, and oxygen is fed through the endotracheal tube by cannula at 6 L/min. After cessation of mechanical ventilation, the patient’s chest should be clearly visible for the remainder of the test. The patient is then monitored carefully for spontaneous respiratory effort and any change in the baseline vital signs. A greater than 10% change in the blood pressure, heart rate, or pulse oximetry is cause to abort the study. Any spontaneous respiratory effort negates the assumption of brain death.12

If an apnea test is aborted because of deterioration in vital signs, in the absence of respiratory effort the diagnosis of brain death is supported and the patient is returned to ventilatory support at the pretest settings. If the patient remains stable in the absence of respiratory effort for up to 10 minutes, an arterial blood gas measurement is repeated and the patient is placed back on ventilatory support at the pretest settings. A Paco2 of 60 torr or greater, or at least two to two and a half times the pretest Paco2, supports the diagnosis of brain death.10,12

CONFIRMATORY TESTING

Electroencephalography, transcranial Doppler imaging, or cerebral flow studies may be done to confirm the diagnosis of brain death as evidenced by clinical examination (absence of brainstem reflexes). The decision to perform confirmatory studies is based on the judgment of the physician declaring brain death and is done in accordance with state laws and individual hospital policy.12

SEQUELAE OF BRAIN DEATH

The inception of brain death presents a challenge to donor stability. Multiple systems are affected once compensatory mechanisms regulated by the central nervous system fail. The sympathetic nervous system accelerates, causing an uncontrolled release of catecholamines. Tachycardia, an increase in systolic blood pressure, and increased cardiac output characterize this “autonomic storm.” Once the catecholamine stores are depleted, this phase ends and hemodynamic instability may ensue. Regulatory mechanisms fail; the ability to control blood pressure and heart rate is lost. Hypotension typically ensues because of a lack of autoregulation, causing vasodilation.11,13

Interventions previously used to control intracranial hypertension (osmotic diuresis, sedation administration) may also contribute to a dangerously low systolic blood pressure (<80 mm Hg). Left untreated, persistent hypotension may threaten viability of organs for transplant. Vigorous but controlled fluid resuscitation can be successful in treating hypotension. Frequently one or more vasopressor agents are infused to maintain a systolic blood pressure of at least 100 mm Hg. The heart rate may vary, and arrhythmias may occur. An initial exaggerated vagal response results in bradycardia but rapidly progresses to tachycardia as a result of catecholamine release and vasopressor support. As the hypothalamus ceases to function, thermoregulatory mechanisms fail and poikilothermy, where body temperature mimics ambient temperature, may develop. Infusion of cold blood products may exacerbate hypothermia. To help maintain the patient’s body temperature, careful attention to the room temperature, infusion of blood through a warmer, and use of an external hyperthermic unit help to maintain a body temperature above 95° F (35° C). Oxygenation is controlled through mechanical ventilation. Aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary contusions, and neurogenic pulmonary edema may impair adequate oxygenation and threaten the viability of the lungs for transplant.11

The posterior pituitary gland ceases to compensate for the feedback mechanism and no longer produces antidiuretic hormone. The subsequent onset of diabetes insipidus can be treated successfully with vasopressin, either subcutaneously or intravenously. Maintaining hemodynamic stability in the brain-dead individual presents a tremendous but rewarding challenge to the critical care staff.11

THE ORGAN DONATION PROCESS

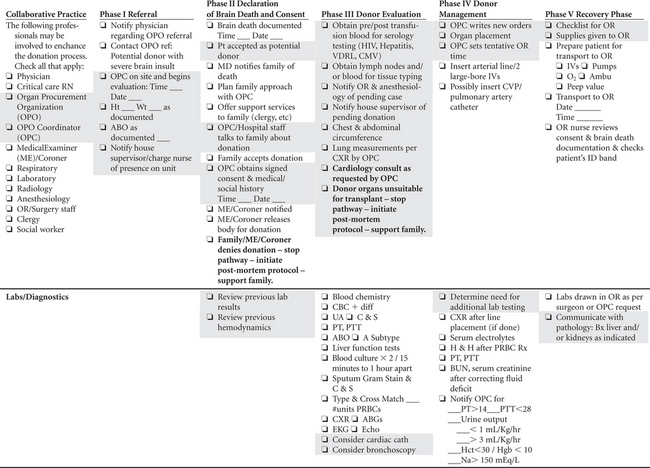

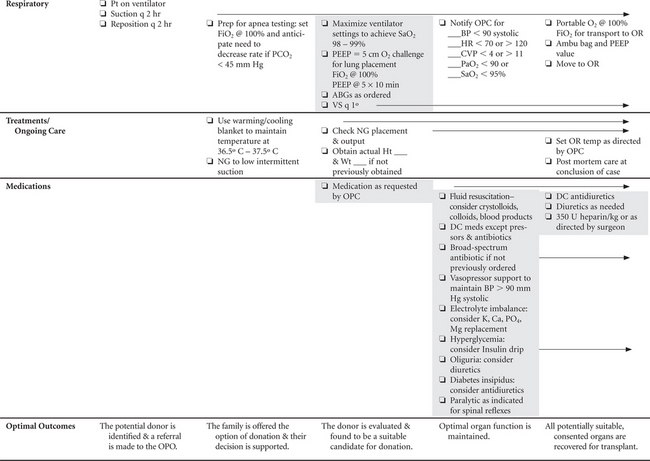

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) developed a critical pathway to assist health care professionals in critical care areas throughout the organ donation process (Table 34–1). The pathway provides an outline for the care of an organ donor from referral through organ recovery. Each step is defined as a phase and is composed of key events, parameters, and diagnostic or clinical values critical to optimal organ function. The donation process is multifaceted and can progress rapidly through each phase, with some events occurring simultaneously. The pathway provides a clear illustration of each phase and identifies the expectations for each. It promotes a collaborative relationship among all disciplines involved in the care of the donor. It is not meant to replace open communication between the OPC and health care team; rather, it keeps all members of the team involved in the process.14 The pathway is designed to be reviewed, revised, and adapted by each hospital in conjunction with its individual OPOs so that current federal, state, or hospital protocols may be incorporated. The pathway can be used by the novice nurse to learn the donation process or as a guide for the experienced nurse.

TABLE 34-1A Critical Pathway for the Organ Donor

|

|

Shaded areas indicate Organ Procurement Coordinator (OPC) Activities

ABGs, Arterial blood gases; BP, blood pressure; Bx, biopsy; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; CMV, cytomegalovirus; C & S, culture and sensitivity; CVP, central venous pressure; CXR, chest x-ray film; DC, discontinue; ECG, electrocardiogram; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; H & H, hemoglobin and hematocrit; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, heart rate; NG, nasogastric tube; OR, operating room; PaO2, partial arterial oxygen pressure; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PRBCs, packed red blood cells; Pt, patient; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; Rx, prescription; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; UA, urinalysis; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory; VS, vital signs.

Reprinted with permission of the United Network for Organ Sharing, Richmond, Va.

TABLE 34-1B Cardiothoracic Donor Management

1. Early echocardiogram for all donors—Insert pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) to monitor patient management (placement of the PAC is particularly relevant in patients with an EF <45% or on high-dose inotropes) < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|