6. The Model of Human Occupation

Embracing the complexity of occupation by integrating theory into practice and practice into theory

Kirsty Forsyth and Gary Kielhofner

Overview

Every day, occupational therapists must answer questions such as:

• What are the occupational needs of this client?

• How do I best support the client to engage in this activity?

• What goals does this client want and need to achieve?

• How can I assist in the achievement of these goals?

To answer these and other practice questions, occupational therapists need comprehensive ways of understanding the client situation.

Evidence suggests that, worldwide, occupational therapists use the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) more than any other framework to address these types of practice question (Law and McColl, 1989, Haglund et al., 2000, National Board for Certification in Occupational Therapy. 2004, Lee et al., 2009 and Taylor et al, 2009). Widespread use of this model reflects the fact that MOHO has the concepts, evidence and practical resources to enable occupational therapists to plan and implement high-quality, evidence-based, client-centred and occupation-focused practice.

This chapter will first take an overview of how and why MOHO was developed. It will then introduce its major concepts and note their relevance to understanding clients and to therapy. Following this, the chapter discusses some of the available resources for using MOHO in practice. Finally, the use of MOHO will be illustrated through a case example.

• MOHO is a client centred, occupation focused, evidence based conceptual model of practice

• MOHO provides a way of embracing the complexity of client?s occupational needs

• MOHO provides specific occupationally focused outcomes measures to measure occupational participation

• MOHO provides a range of therapeutic intervention options

• MOHO has been applied successfully across cultures and used extensively internationally

Why and how MOHO was developed

From the 1960s onward, there was a recognition that occupational therapy had become too concerned with remediating impairment and needed to recapture its original focus on occupation (Reilly, 1962, Shannon, 1970 and Kielhofner and Burke, 1977). The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) was the first occupation-focused model to be introduced in the profession (Kielhofner, 1980a, Kielhofner, 1980b, Kielhofner and Burke, 1980 and Kielhofner et al., 1980). It was developed by three occupational therapy practitioners who wanted to organize concepts that could guide their delivery of occupation-focused practice. In the three decades since MOHO was first formulated, numerous practitioners and researchers throughout the world have contributed to its development. Today, a literature of approximately 500 published works undergirds this model, making it the most evidence-based, occupational-focused model in the field.

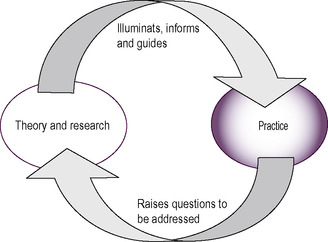

The developers of this model have always sought to ensure that its concepts and tools are relevant and useful in practice. MOHO has been developed through an approach called ‘the scholarship of practice’. This approach emphasizes the importance of an ongoing dialogue between theory/research and practice (Taylor et al 2002). Consequently, the scholarship of practice represents a commitment to scholarship, which supports occupational therapy practice, as well as a commitment to partner clinicians who are involved in the application of MOHO (Fig. 6.1). Moreover, the collaboration ensures that the needs and circumstances of practice shape theory development and research. All participants (for example, clients, therapists, managers, educationalists, students, researchers) take on the role of ‘practice scholars’, sharing responsibility for developing and applying MOHO. MOHO is, therefore, driven by practice concerns, and practice shapes how its theory is articulated and applied. This approach has not only assured MOHO’s usefulness in practice, but has also enhanced the profile of occupational therapists, resulting in greater client understanding and satisfaction, and more respect for the occupational therapy contribution made by managers, policy-makers and interdisciplinary colleagues.

|

| Fig 6.1 • Scholarship of practice. Reproduced with the permission of Professor G. Kielhofner from Challenges of the New Millennium: Keynote Address, WFOT Conference, Stockholm 2003. |

In 1985 the book A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application introduced an expanded theory and a wide range of clinical applications (Kielhofner 1985). Revisions of the model were completed in 1995 and 2002, and the fourth edition (Kielhofner 2008) presents the authoritative and most current understanding of this theory and its application; it should be considered the primary reference on the model. For therapists who wish to apply MOHO, this text is a necessary resource.

Other published literature provides additional sources of theoretical discourse, discussions of programmatic applications, cases examples and research findings. The literature on this model is published worldwide. A current bibliography of literature, an evidence-based search engine and hundreds of evidence briefs, along with a wide range of assessment tools and intervention protocols on the model, can be found on a website: http://www.moho.uic.edu/. The website also provides an opportunity to join a list serve where students and practitioners can post practice questions and receive expert advice.

MOHO theory

A conceptual model of practice proposes theory to address certain phenomena with which the model is concerned (Kielhofner 2008). MOHO provides theory to explain occupation and occupational problems that arise in association with illness and disability. Its concepts address:

• the motivation for occupation

• the routine patterning of occupational performance

• the nature of skilled performance

• the influence of environment on occupation.

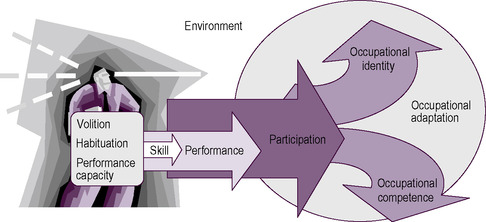

The following section will address the main conceptual ideas in MOHO (Fig. 6.2), namely:

|

| Fig 6.2 • MOHO concepts. Reproduced from Kielhofner, G., 2008. A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application, 4th edn, published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore |

1. embracing the complexity of human occupation

2. components of the person

3. environment

4. occupational performance.

Embracing the complexity of human occupation in practice

MOHO recognizes that occupation (i.e. what a person does in work, play and self-care) is influenced by many factors inside and outside the person. MOHO further emphasizes that each person’s inner characteristics and external environment are linked together into a dynamic whole. In order to embrace this complexity, MOHO theory includes a range of concepts. These concepts seek not only to offer explanations of the factors that influence occupation, but also to provide a framework for gathering data about a client’s circumstances, generating an understanding of the client’s occupational strengths and limitations, and selecting and implementing a course of occupational therapy.

Further, MOHO theory views therapy as a process in which people are helped to do things in order to shape their occupational abilities and occupational identities. MOHO provides a framework for successfully and meaningfully engaging people in occupations, which helps to maintain, restore, or reorganize their occupational lives.

Components of the person

To explain how occupational participation is chosen, patterned and performed, MOHO conceptualizes people as composed of three interconnected ideas:

• volition

• habituation

• performance capacity.

Volition refers to the process by which persons are motivated toward and choose what they do. Habituation refers to a process whereby doing is organized into patterns and routines. Performance capacity refers to both the underlying mental and physical abilities and the lived experience that shapes performance. Each of these three components of the person is discussed in more detail below.

Volition

Volition refers to the process by which people are motivated toward and choose what they do. The concept of volition asserts that all humans have a desire to engage in occupations, and that this desire is shaped by ongoing experiences as we do things. Volition consists of thoughts and feelings that occur in a cycle of anticipating possibilities for doing, choosing what to do, experiencing what one does, and subsequent interpretation of the experience. These thoughts and feelings are concerned with three issues:

1. how effective one is in acting on the world (personal causation)

2. what one holds as important (values)

3. what one finds enjoyable and satisfying (interests).

Personal causation

Personal causation is reflected in our awareness of present and potential abilities (Harter, 1983 and Harter and Connel, 1984) and our sense of how able we are to do what we want to do (Rotter, 1960 and Lefcourt, 1981). Our own culture and social environment tell us what capacities we should have and why they matter. For example, a performer on stage, a taxi driver in a large city, a secondary school teacher, and a farmer in the countryside will each be concerned about very different kinds of ability. Also, developmental level will affect the experience of personal causation. A young child typically will be concerned with developing such skills as walking and playing with toys. An older child may be mostly concerned with school performance and ability to get along with peers and perform in sports. Adolescents usually begin to think about capacity for further education and entry into a line of work. Adults will focus on such things as the capacity for work performance and management of other adult responsibilities such as parenting. Older adults will often be concerned with loss of capacity associated with ageing and how to maintain abilities for personally important things.

Consequently, personal causation is never static, but rather a dynamic unfolding set of thoughts and feelings about our capacities and our efficacy in doing what we want to do. Our unique personal causation influences how we anticipate, choose, experience and interpret what we do. Consequently, the thoughts and feelings that make up personal causation are powerful motivational influences and they also guide how we experience what we do and how we look forward to the future.

Values

Choices of occupations are also influenced by our values. Values are beliefs and commitments that define what we see as good, right and important; they shape our sense of what is worth doing, how we ought to act, and what is the right way of doing things (Lee 1971). The child who plays nicely with other children because he has learned that playing in this way is important is expressing values. The worker who feels she needs to excel, the father who believes it is important to spend time with his children, and the old person who feels compelled to volunteer his services to his church are all examples of people whose values shape what they do. When we cannot live up to our values, we may feel guilty or inadequate and we experience a lack of meaning (Bruner 1990). The worker who has a stroke and subsequently loses his job, the mother whose mental illness interferes with parenting her child, the child whose learning disability makes it difficult to do as well in school as he thinks he should, and the elderly person whose fear of falling interferes with being able to engage in meaningful occupations are all examples of persons who are unable to enact their values.

Interests

Being interested in an occupation means that one feels an attraction based on anticipation of a positive experience in doing that occupation. The experience of pleasure and/or satisfaction in doing something may come from positive feelings associated with either the exercise of capacity, intellectual or physical challenge, fellowship with others, aesthetic stimulation, or other factors. We are more likely to enjoy what we can perform with some level of proficiency when skill is involved in the performance. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) describes flow, a form of ultimate enjoyment in occupations that occurs when a person’s capacities are optimally challenged. Often, this preference is manifested as a pattern of related interests such as athletic interest or cultural interests, including theatre and art. Preferring certain occupations over others influences what we are motivated to choose to do.

Illness or impairment can interfere with doing what one is interested in. For instance, a person might lose the capacity to do something he previously enjoyed, or an individual may find that engaging in an interest is no longer pleasurable because it evokes too much pain or fatigue. Persons with depression may find that they no longer enjoy doing what was previously pleasurable. Being able to engage in occupations that interest us and provide us with enjoyment and satisfaction is essential to well-being, and when illness or impairment interferes with this engagement, quality of life is reduced.

Summary

Our interests, values and personal causation affect what everyday activity we are motivated to do, what activities we choose to engage in and how we experience doing them. Illness and disability can interfere with volition in many ways. When this is the case, occupational therapists need to be able to assess and address volitional problems.

Additionally, volition is critical to the occupational therapy process. In order to provide therapy, occupational therapists must enable clients to engage in meaningful activity. Choosing a therapeutic activity and experiencing it as meaningful is a function of volition. Therapy cannot be meaningful unless occupational therapists attend to their client’s volition.

The outcomes of therapy also depend on volition. It is not enough to improve a client’s capacity. If the client leaves therapy and has no volitional motivation to use that capacity by engaging in activities of value and interest, then the client will not use what he or she has gained in therapy. Thus, therapy should always support the client’s volition. Good therapy outcomes require that clients will choose to use their capacity, to develop new capacities, or make adjustments for their limitations because they can see these efforts as providing a life with value and satisfaction over which they can exercise reasonable control.

Habituation

Occupation is more than simply doing things. Every person has some kind of life pattern that is made up of everyday routines and roles. Habituation refers to the process by which people organize their occupational performance into the recurrent patterns of behaviour. These patterns integrate us into our physical and temporal world (when and where we do things) and our social and cultural world (doing things that reflect what we are expected to do by virtue of our position in society). Moreover, they allow us to carry out our daily lives efficiently and automatically. Habituated patterns of action are governed by:

• habits

• roles.

Habits

Habits involve learned ways of doing occupations that unfold automatically. The way we bathe and dress ourselves each morning, and how we drive, take a bus or ride a bike to work or school are examples of habits. We learn these habits through repeated experience. When we learn a habit, we acquire a way of appreciating and behaving in our familiar environments. So, for instance, we recognize the ring of the alarm clock as an indication that it is time to rise and bathe and dress; we know where to find the toothbrush and reach for it without thinking. We know how to turn on the shower and do it unreflectively. Because we do not have think about these things as we go about our morning routine, our routines take less effort and concentration. Our habits always involve cooperation with our environment (Dewey 1922). When our environment changes, our habits may no longer work automatically. For instance, when we find ourselves in an unfamiliar environment such as a hotel room, we may suddenly find that we have consciously to think about and figure out how to do a routine task such as turning on the shower. As the example illustrates, when habits cannot guide our behaviour automatically, it takes more concentration and effort to complete our routines. Consequently, habits give us our bearings throughout daily life and allow us to do routine things with relative ease.

Habits also organize our underlying capacities. When we reach for the toothbrush or turn on the shower, we are using our vision, our cognition and our motor capacity. If we were to experience a loss of any of these capacities, our habits would disintegrate. For example, if the power is out and one has to feel one’s way about the bathroom at night without the benefit of sight, habits go out of the window. If one has a broken arm and one’s dominant hand is in a cast, simple things like turning on the shower, brushing one’s teeth or putting on clothes take a lot more thinking and effort or may be impossible. When clients develop impairments, their habits become disrupted and their everyday routines take additional effort and thought or cannot be done without help. When one suddenly must use a wheelchair, the environment is changed and familiar habits no longer work. Getting into the shower and reaching to the medicine cabinet for the toothbrush are suddenly no longer habitual or possible. All the familiarity and ease of everyday life is disrupted. An important function of occupational therapy is to help clients develop new habits of everyday life in order to restore some of the ease and familiarity of daily life.

Roles

People see themselves as students, workers and parents, and recognize that they should behave in certain ways to enact these roles. Much of what we do is done as a spouse, parent, worker, student and so on (Mancuso & Sarbin 1983). The presence of these and other roles helps assure that what we do is regular (e.g. we go to school or work according to a schedule). Roles also give us a sense of identity and belatedly a sense of what we are obligated to do. When we tell someone we are a parent, a student, a worker or a member of some group, we are telling them who we are. Moreover, we know what is expected of us in those roles. Parents take care of children. Students attend lectures, study and take exams. Members of a bicycling club plan and go on bicycle trips together.

The roles that we have internalized serve as a kind of framework for looking out on the world and for engaging in occupation. When one is engaging in an occupation within a given role, it may be reflected in how one dresses, one’s demeanour, the content of one’s actions and so on. For instance, one would dress differently for work from when engaging in a leisure role. We do quite different things when we are in the role of student from when we are in the role of a friend.

Having an impairment can compromise one’s ability to engage in meaningful life roles. If the impairment is severe, it can prevent or alter the way a person engages in all of their life roles. People with chronic disabilities often inhabit many fewer roles than those who do not have impairments. As a consequence, they have fewer opportunities to develop a sense of identity and to fill their lives with meaningful activities. In order to understand fully how a disability has influenced a client, the occupational therapist must understand its impact on their roles. Moreover, the aim of occupational therapy should be to support clients to enable them to engage in those roles that are most important or necessary for them.

Summary

Habituation regulates the patterned, familiar and routine features of what we do. Habits and roles give regularity, character and order to what we do and how we do it. They make our everyday lives familiar and they give us a sense of who we are. Disability can invalidate established habits and roles. Having a disability may require one to develop new habits for managing everyday routines and it may interfere with being able to engage in a role or alter how one can do that role. Understanding how a disability affects any person requires that the occupational therapist pays careful attention to the client’s habituation.

Moreover, it is not sufficient that a client develops skills for doing everyday routines; it is also critical that the client develops the habits to integrate these skills into effective ways of doing everyday life tasks. Similarly, having abilities does little good, if clients are not able to access and identify with roles that call upon them to use those abilities. Therapy that focuses only on augmenting capacity without considering how the client will go about organizing everyday life is incomplete. Moreover, knowing what roles and habits are part of a client’s life will also provide important information to enable us to prioritize the kinds of skill development on which to focus. Clients do not simply do things; they do them in order to enact daily routines and discharge their roles.

Performance capacity

The capacity for performance is affected by the status of one’s musculoskeletal, neurological, cardiopulmonary and other bodily systems. A number of occupational therapy frameworks provide detailed concepts for understanding performance capacity. For example, the biomechanical framework seeks to explain human movement as the function of a complex organization of muscles, connective tissue and bones (Trombly 1989), while the sensory integration framework (Ayres, 1972, Ayres, 1979 and Ayres, 1986) explains how the brain organizes sensory information for executing skilled movement. Because these frameworks already address performance capacity, MOHO does not address this aspect of performance capacity. Consequently, occupational therapists using MOHO routinely use other frameworks for understanding and addressing performance capacity.

MOHO (Kielhofner et al 2008) concepts offer a different but complementary way of thinking about performance capacity. This view of performance capacity builds upon phenomenological concepts from philosophy (Husserl, 1962 and Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and focuses on the subjective experience of performing. It asks occupational therapists to pay more attention to how it feels to perform with a disability. By having a better understanding of a client’s pain, fatigue, confusion or other subjective aspects of performance, therapists can be more client-centred and more helpful in assisting clients to learn or relearn skills.

Interweaving of volition, habituation and performance capacity

The things we do reflect a complex interplay of our motives, habits and roles, and performance capacity. Volition, habituation and the subjective experience of performance always operate in concert with each other. We cannot fully understand a client’s occupation without considering all these contributing factors. For example, a person with low personal causation will tend to feel anxious when attempting to perform. This anxiety in turn can negatively affect performance. Another example is that if a person does not have interests and values that lead him to use his capacities, those capacities will diminish through disuse. For this reason, it is important that occupational therapists gather information about all the aspects of a client (performance capacity, values, interests, personal causation, roles and habits) in order truly to understand that client and provide the best services.

The environment

Just as volition, habituation and performance capacity are inter-related and interdependent, people and their environments are also inseparable (Kielhofner 2008). Our environments offer us opportunities, resources, demands and constraints. Whether and how these environmental potentials affect us depends on our values, interests, personal causation, roles, habits and performance capacities. Because each individual is unique, any environment will have somewhat different effects on each individual within it.

The physical environment consists of natural and human-made spaces and the objects within them. Spaces can be the result of nature (e.g. a forest or a lake) or the result of human fabrication (e.g. a house, classroom or theatre). Similarly, objects may be those that occur naturally (e.g. trees and rocks) or those that have been made (e.g. books, cars and computers). The social environment consists of groups of persons, and the occupational forms or tasks that persons belonging to those groups perform. Groups allow and prescribe the kinds of thing their members can do. Occupational forms or tasks refer to the things that are available to do in any social context (for example, in a classroom the kinds of thing that are typically done include writing notes, giving a lecture, answering questions, taking exams and so forth). Every context has certain occupational forms or tasks associated with it.

Any setting within which we perform is made up of spaces, objects, occupational forms/tasks and/or social groups. Typical settings in which we engage in occupational forms are the home, neighbourhood, school or workplace.

The environment can be both a barrier and an enabler for disabled persons. For example, snow dampens the sound used by blind persons to help navigate without sight and may make the pavement inaccessible to the wheelchair user. Much of the built environment limits opportunities and poses constraints on those with disabilities because it often has been designed for persons without impairments. On the other hand, careful design of spaces can facilitate daily functioning of disabled persons. Similarly, while most fabricated objects in the environment are created for use by able-bodied, sighted, hearing and cognitively intact individuals, there are also a large number of objects designed to compensate for impairments. Occupational therapists are experts in providing and training clients in the use of these specialized objects.

People with a physical and mental impairment often contradict cultural values, making others uncomfortable and evoking a range of reactions. These attitudes can limit the person with disability. Moreover, disability may remove people from or alter the positions they can assume in social groups. The occupational forms available to the person with a disability may be limited or altered. Performance limitations can make doing some occupational forms impossible. Persons with disabilities often must give up or relinquish to others occupational forms that have become impossible to do.

In short, the physical and social environment can have a multitude of positive or negative impacts on the disabled person, which can make all the difference in that person’s life. The environment is not only a pervasive factor influencing disability. It is a critical tool for supporting positive change in the disabled person’s life. A therapist may purposefully alter the physical setting to remove constraints or to facilitate function. An example of this is a ramp that replaces inaccessible steps. Therapists can remove objects that are barriers or provide objects such as assistive technology that facilitate functioning. The therapist may provide, monitor or seek to change social groups such as families or work colleagues. Finally, the therapist may provide or help a client select occupational forms to undertake, or to modify how an occupational form is done.

Understanding occupational performance

Personal causation, values and interests motivate what we choose to do. Habits and roles shape our routine patterns of doing. Performance capacities and subjective experience provide the capacity for what we do. The environment provides opportunities, resources, demands and constraints for our doing. We can also examine the doing itself and what consequence it has over time. Doing can be examined at different levels:

• skills

• occupational performance

• occupational participation

• occupational identity/occupational competence

• occupational adaptation.

Skills

Within occupational performance we carry out discrete purposeful actions called skills. For example, making a cup of tea has a culturally recognizable occupational form in the UK. To do so, one engages in such purposeful actions as gathering together tea, kettle and a cup, handling these materials and objects, and sequencing the steps necessary to brew and pour the tea. These actions that make up occupational performance are referred to as skills (Fisher and Kielhofner, 1995, Fisher, 1999a and Forsyth et al., 1998). In contrast to performance capacity (which refers to underlying ability, e.g. range of motion, strength, cognition), skill refers to the discrete actions seen within an occupation performance. There are three types of skill: motor skills, process skills, and communication and interaction skills.

If a person has difficulty ‘reaching’, an occupational therapist may conclude that the client has a limited range of motion in the shoulder joint. However, using Figure 6.2 to support theoretical clinical reasoning, we could hypothesize other reasons for the client not ‘reaching’. For example, the client may not think he has the capacity to reach (personal causation); he may not see the activity as important and therefore fail to reach (values); he may not find the activity satisfying or enjoyable and therefore fail to reach (interest); it may not be part of his role responsibilities and therefore he fails to reach as he knows someone else will do this for him (roles); the environment may not be supporting the reach; the occupational form may not be within the person’s culture and so they do not know they need an object to complete the occupational form and so fail to reach; and so on. Skills can therefore be influenced by a range of personal and environmental factors. Having a theoretical framework supports clinical reasoning to understand why a client is having difficulty exhibiting skill to complete the occupational form.

Occupational performance

When we complete an occupational form or task, we perform. Occupational forms for a lecturer may include lecturing, writing, administering and marking exams, creating courses and counselling students. Taking care of ourselves may involve performing the occupational forms of showering, dressing and grooming. Other examples of occupational performance are when persons do such tasks as walking the dog, baking a chicken, vacuuming a rug or mowing the lawn. These people are performing those occupational forms.

Occupational participation

Participation refers to engagement in work, play, or activities of daily living that are part of one’s sociocultural context and are desired and/or necessary to one’s well-being. Examples of occupational participation include working in a full- or part-time job, engaging routinely in a hobby, maintaining one’s home, attending school and participating in a club or other organization. This definition is consistent with the World Health Organization’s view that participation is ‘taking part in society along with their experiences within their life context’ (World Health Organization 1999, p.19). Each area of occupational participation involves a cluster of related things that one does. For example, maintaining one’s living space may include paying the rent, doing repairs, and cleaning.

Occupational identity and occupational competence

Our participation helps to create our identities. Occupational identity is defined as a composite sense of who one is and who one wishes to become as an occupational being, generated from one’s history of occupational participation. Occupational identity includes one’s sense of capacity and effectiveness for doing; what things one finds interesting and satisfying to do; who one is, as defined by one’s roles and relationships; what one feels obligated to do and holds as important; a sense of the familiar routines of life; perceptions of one’s environment and what it supports and expects. These are garnered over time and become part of one’s identity. Occupational identity reflects accumulative life experiences that are organized into an understanding of who one has been and a sense of desired and possible directions for one’s future.

Occupational competence is the degree to which one sustains a pattern of occupational participation that reflects identity. Competence has to do with putting your identity into action. It includes fulfilling the expectations of one’s roles and one’s own values and standards of performance; maintaining a routine that allows one to discharge responsibilities; participating in a range of occupations that provide a sense of ability, control, satisfaction and fulfilment; and pursuing one’s values and taking action to achieve desired life outcomes.

Occupational adaptation

Occupational adaptation is the construction of a positive occupational identity and achieving occupational competence over time in the context of the environment.

Resources for practice

MOHO was initiated with the specific goal of developing resources to guide and enhance occupation-focused practice. Practitioners have collaborated in the development of a wide range of tools for partnerships. Academic/practice partnerships were built around how the tools developed. This ensured that the tools were theoretically driven and had robust research to support them while simultaneously being flexible and useful within busy clinical workplaces.

MOHO tools are specifically built to support occupation-focused practice. Examples are:

Box 6.1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

MOHO assessment tools

Overview assessments

Occupational Performance History Interview (OPHI-II)

As a historical semi-structured interview, the OPHI-II seeks to gather information about a patient or client’s past and present occupational performance. The OPHI-II is a three-part assessment, which includes:

• a semi-structured interview that explores a client’s occupational life history

• rating scales that provide a measure of the client’s occupational identity, occupational competence and the impact of the client’s occupational behaviour settings

• a life history narrative designed to capture salient qualitative features of the occupational life history.

Occupational Circumstances Interview and Rating Scale (OCAIRS)

The OCAIRS is a semi-structured interview focused on the present and seeks to understand clients’ occupational abilities on the full range of MOHO issues. It is an outcome measure. It is appropriate for clients who are conversational and is used when time is limited, as it is shorter than the OPHI-II interview.

Assessment of Occupational Functioning (AOF)

The AOF is a semi-structured interview, designed to identify strengths and limitations in areas of occupational functioning derived from MOHO (personal causation, values, roles, habits and skills). The AOF includes two parts:

• an interview schedule

• a rating scale.

Occupational Self-Assessment (OSA) and the Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA)

The OSA is an update of the Self-Assessment of Occupational Functioning (SAOF) and is designed to capture clients’ perceptions of their own occupational competence and of the impact of their environment on their occupational adaptation. As such, the OSA is designed to be a client-centred assessment, which gives voice to the client’s view. Once clients have had an opportunity to assess their occupational behaviour and their environments, they review the items in order to establish priorities for change, which can be translated into therapy goals.

Model of Human Occupational Screening Tool (MOHOST) and Short Child Occupational Profile (SCOPE)

These are relatively new assessments based on MOHO. Similar in format and administration, they were developed with clinicians in response to their request for a comprehensive assessment that is quick and simple to complete. MOHOST and SCOPE may be scored by the therapist using any combination of observation, interview, information from others who know the client, and chart audit. Because of their flexibility, the two tools can be used in a wide range of settings and with a wide range of clients. Moreover, the tools can be administered in a way that is client-centred.

Observational assessments

Assessment of Communication and Interaction Skills (ACIS)

The ACIS is a formal observational tool designed to measure an individual’s performance in an occupational form and/or within a social group of which the person is a part. The instrument aims to assist occupational therapists in determining a client’s ability in discourse and social exchange in the course of daily occupations.

Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS)

The AMPS (Fisher 1999b) represents a fundamental and substantive reconceptualization in the development of occupational therapy functional assessments. The AMPS is a structured, observational evaluation. It is used to evaluate the quality or effectiveness of the actions of performance (motor and process skills) as they unfold over time when a person performs daily life tasks.

Volitional Questionnaire (VQ) and the Paediatric Volitional Questionnaire (PVQ)

Traditionally, it has been difficult to assess volition in clients who have communication and cognitive limitations, due to the complex language requirements of most assessments of volition. The Volitional Questionnaire is an attempt to recognize that, while such clients have difficulty formulating goals or expressing their interests and values verbally, they are often able to communicate them through actions. The client is observed in a number of occupational behaviour settings so that a picture of the person’s volition and the environmental supports required to support the expression can be identified.

Self-reports

Interest Checklist and the Paediatric Interests Profiles (PIP)

Although a number of versions of the Interest Checklist exist, the revised version appears to be the one most commonly used by occupational therapists utilizing the Model of Human Occupation and will be the one referred to in this discussion. This version consists of 68 activities or areas of interest. A revision within the UK is currently under way. There is a paediatric version available.

National Institutes of Health Activity Record (ACTRE)

The NIH ACTRE was developed as an outcome measure for a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This instrument provides a 24-hour log of a patient’s activities and is an adaptation of the Occupational Questionnaire (described below). The ACTRE aims to provide details of the impact of symptoms on task performance, individual perceptions of interest, significance of daily activities, and daily habit patterns.

Occupational Questionnaire (OQ)

The OQ is a pen-and-paper, self-report instrument that asks the individual to provide a description of typical use of time and utilizes Likert-type ratings of competence, importance, and enjoyment during activities. The client completes a list of the activities they perform each half-hour on a typical weekday. After listing the activities, the client is asked to answer four questions for each activity.

Role Checklist

The Role Checklist is a self-report checklist that can be used to obtain information about the types of role people engage in and which organize their daily lives. This checklist provides data on an individual’s perception of their roles over the course of their life and also the degree of value, i.e. the significance and importance that they place on those roles. The Role Checklist can be used with adolescents, adults or geriatric populations.

Vocational assessments

Worker Role Interview (WRI)

The WRI is a semi-structured interview designed to be used as the psychosocial/environmental component of the initial rehabilitation assessment process for the injured worker. The interview is designed to have the client discuss various aspects of their life and job setting that have been associated with past work experiences. The WRI combines information from an interview with observations made during the physical and behavioural assessment procedure of a physical and/or work capacity assessment. The intent is to identify the psychosocial and environmental variables that may influence the ability of the injured worker to return to work.

Work Environment Impact Scale (WEIS)

The WEIS is a semi-structured interview designed to gather information about how individuals with disabilities experience and perceive their work settings. The focus of the interview is the impact of the work setting on a person’s performance, satisfaction and well-being. An important concept underlying this scale is that workers are most productive and satisfied when there is a ‘fit’ or ‘match’ between the worker’s environment and their needs and skills. Hence, the same work environment may have a different impact on different workers. It is important to remember that the WEIS does not assess the environment. Rather, it assesses how the work environment affects a given worker.

School assessments

Occupational Therapy Psychosocial Assessment of Learning (OT PAL)

The OT PAL is an observational and descriptive assessment tool. It assesses a student’s volition (ability to make choices), habituation (roles and routines), and environmental fit within the classroom setting. The observational portion consists of 21 items that address the major areas of making choices, habits/routines and roles. In addition to the observation portion, there is a pre-observation form and interview guidelines. The pre-observation form is designed to gather environmental information, as well as assist in determining an appropriate time to complete the observation. The semi-structured interviews of the teacher, the student and the parent(s) are designed to have the teacher, student and parent describe various psychosocial aspects of learning related to school.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree