Chapter 20 The Management of Delayed and Non-unions of the Distal Humerus

Introduction

A non-united fracture of the distal humerus threatens the function of the entire upper limb. The involved elbow joint may be stiff, or grossly unstable, painful and associated with peripheral nerve dysfunction.1 The non-union will compromise function of either the ipsilateral shoulder, hand, or both.

While fractures of the distal humerus are uncommon (2–6% of all fractures),2,3 the unique regional anatomy, with the articular surfaces supported by limited bone yet subject to substantial reactive joint forces in normal daily activities, presents significant impediments to successful surgical fixation and functional outcome.

Background/aetiology

As our patients live longer, the incidence of upper extremity fractures including those involving the distal humerus is increasing. In addition, what we are seeing are more complex fractures occurring at or distal to the olecranon sulcus and associated with osteoporotic bone. These factors are providing the surgeon with an increasing challenge to achieve stable internal fixation that facilitates bone healing without complication. It is also leading to more interest in the use of total elbow arthroplasty as a primary form of fracture treatment.4 Closed or open distal humeral fractures are also seen in younger patients associated with higher-energy injuries. In each of these situations failure of bone healing has become a well-recognized adverse sequela.5 Additional risk factors contributing to non-union include obesity, alcoholism and patient unreliability, as well as advanced osteoporosis.6

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

The patient’s physical examination involves a careful assessment of the entire upper limb. The mobility of the adjacent joints including the ipsilateral shoulder, forearm, wrist and hand may be compromised from prolonged immobilization, postsurgical swelling or peripheral nerve injury or compression. The latter is particularly relevant as ulnar nerve compromise is now well recognized as a sequela of elbow trauma and surgical reconstruction and may be the source of pain as well as motor and sensory dysfunction in the hand.1

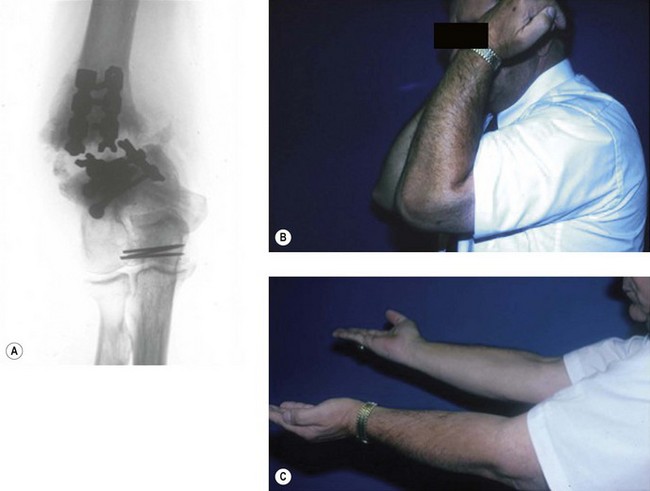

Examination of the affected elbow must document the location and extent of previous surgical incisions, the adequacy and compliance of the soft tissue envelope, and joint mobility and/or instability. A grossly unstable or flail non-union will prevent the patient from effectively lifting the forearm against gravity (Fig. 20.1).

Owing to the disturbed local anatomy at the non-union site, standard radiographs of the elbow may not adequately define the morphology of the nonunion. While evaluation of the original fracture and/or postoperative radiographs will be helpful, these are not always available. The distal articular fragment(s) of the non-union may be flexed due to capsular contracture and appear on the radiographs to be anatomically smaller than in reality.7 In these situations, or when non-unions occur within the articular surfaces, 3-D CT imaging may be extremely useful.

Treatment options will include a hinged functional brace for patients too infirm for surgery or who do not wish to undergo an additional surgical procedure; realignment with internal fixation and capsular release, or total elbow arthroplasty.1

Summary Box 20.1

A non-united fracture of the distal humerus creates a dysfunctional upper limb.

Evaluation of the patient must include the function and mobility of the shoulder, wrist and hand.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

The tactics of surgical treatment of a distal humerus non-union will depend upon the location and morphology of the non-union. Non-unions may be classified as supracondylar, intra-articular, or combined extra- and intra-articular (Table 20.1).7

Table 20.1 Classification of distal humeral non-unions based upon anatomical location

| Supracondylar | Flail elbow – gross instability at the non-union site with a synovial membrane that will require debridement. The bone ends characteristically are sclerotic |

| Bone loss – substance loss that may require an interposition structural graft | |

| Combined extra- and intra-articular | The non-union involves both the supracondylar level and extends into the articular components |

| Intra-articular | The non-union is characterized primarily by involvement of the articular condyles |

| Osteochondral | This represents a subset of articular non-unions where the original fracture involved a shear injury to the anterior articular surface |

| Low transcondylar | Non-unions at this level will have very distorted bony anatomy of the distal fragment and require modification of internal fixation methods |

| Infected | These may be salvaged but represent unique injuries |

Non-union at the supracondylar level

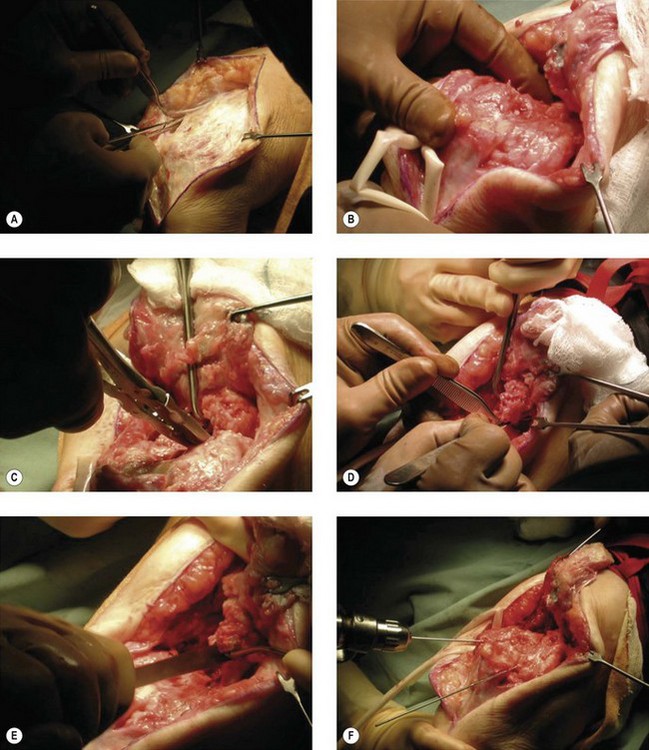

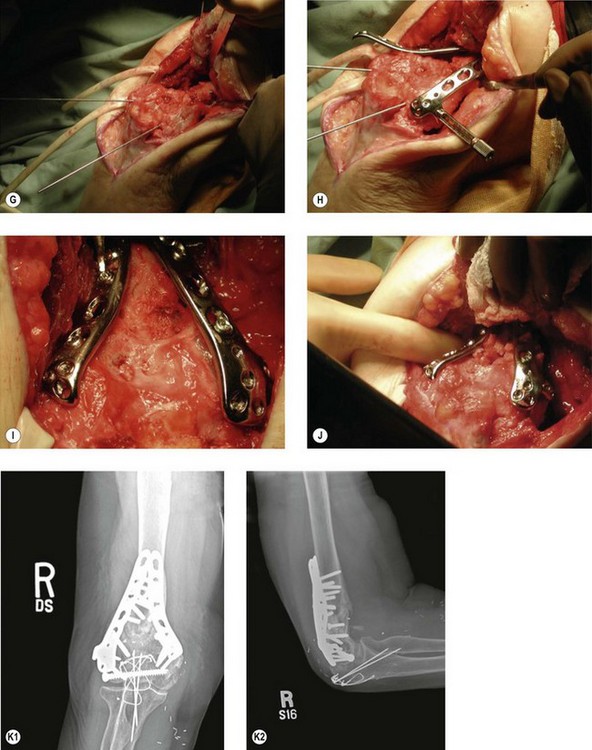

We prefer using a sterile tourniquet, although some might avoid this owing to the potential length of the reconstructive procedure. A straight dorsal surgical incision provides extensile exposure; however, prior incisions must be considered and included if possible (Fig. 20.2 (video)).

The ulnar nerve must be carefully mobilized, preferably for at least 6 cm proximal and distal to the cubital tunnel. The nerve is commonly surrounded by fibrosis that will limit its normal excursion following elbow mobilization, unless sufficiently mobilized and placed into the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 20.3).

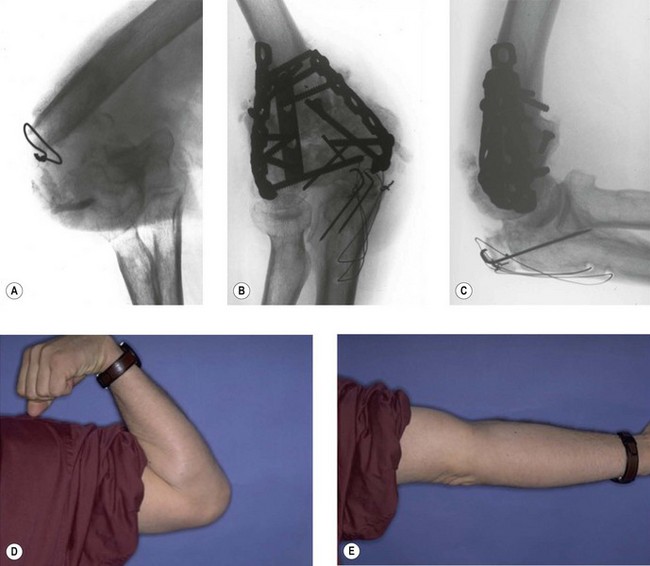

The techniques of plate fixation will vary considerably based on the size of the distal fragment, the extent of the underlying osteoporosis, as well as the type and availability of implants. Although anatomically shaped implants have been developed for the distal humerus, the often-distorted anatomy that occurs with non-unions will frequently require contouring of standard plates. A third plate has proven to be useful in cases where limited bone exists in the distal fragment particularly if it is only possible to achieve one screw purchase per plate.8 Given that there is often incomplete bony contact, cancellous iliac crest graft should be used to fill in areas of bony defect (Fig. 20.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree