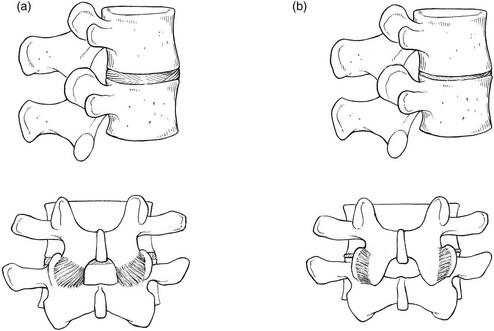

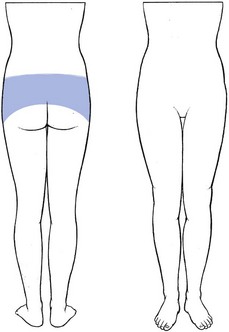

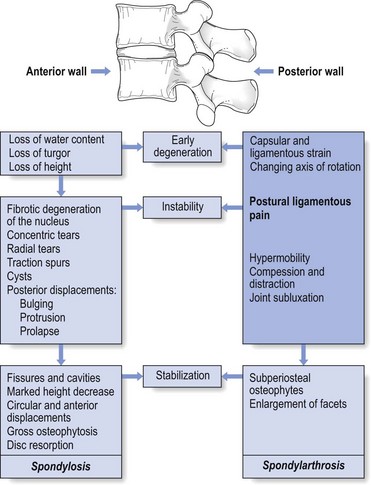

34 Lesions of the posterior arch (posterior ligaments and facet joints) have long been considered an important source of low back pain. However, the classic work of Mixter and Barr in 1934, which focused attention on the disc, overshadowed the importance of posterior ligamentous lesions. Disc lesions must be considered to be the main source of backache and sciatica but ligamentous problems remain a possible basis for lumbar symptoms. In lesions of the lumbar spine, discs take the strain first but it is obvious that any change in height and mechanical properties of the disc will also influence the posterior ligamentous structures. There is anatomical evidence for free nerve endings in the posterior ligaments and the capsule of the facet joint.1–3 In addition, a number of investigations have shown that low back pain can be produced by direct stimulation of facet joints and ligaments.4–6 Although ligamentous pain is difficult to prove by technical investigations, it is possible to identify it on clinical grounds.7–10 The ultimate proof of a posterior arch lesion is the improvement of pain and dysfunction after diagnostic infiltration with local anaesthesia. The structures discussed in this chapter are the supra- and interspinous ligaments, the facet joints, and the intertransverse and the iliolumbar ligaments. The behaviour of the sacroiliac, sacrospinal and sacrotuberous ligaments shows some similarity to that of the lumbar ligaments; however, their disorders and treatment are detailed in Chapter 43. Most of the stabilizing support for the lumbar spine in standing, sitting and flexion–extension is determined by the tension of the ligaments rather than the strength of the paravertebral muscles (Wyke11: Ch. 11; Stokes and Frymoyer12). Postural strain, therefore, will affect the nociceptors in the capsules of the facet joints and the ligaments of the posterior arch, which happens when prolonged or increased postural pressure falls on normal tissues, or when abnormal (traumatized, inflamed or deformed) ligaments are subjected to normal postural stress. The first – prolonged or increased static loading of normal and healthy ligamentous tissues – is the ‘postural’ syndrome. The second – symptoms arising from abnormal (degenerated or inflamed) tissues subjected to normal mechanical stress – is the ‘dysfunction’ syndrome. Pathological changes in the structures responsible for the pain are not present. Only the maintenance of a stress on a normal tissue creates this type of pain – an example of what has been termed ‘the bent finger’ syndrome; if a finger is bent backwards, sooner or later pain will appear.9 If sufficient force is applied for long enough, mechanical deformation of the sensitive structures in the involved tissues induces pain. It is this lumbar aching that everyone experiences when a particular posture is maintained for a long period. Pain increases in intensity the longer the time spent in the position, but the moment another position is adopted the pain will gradually disappear (Box 34.1). Although, in the postural syndrome, the structures are normal and pain is initially produced by subjecting these structures to increased mechanical stresses, it is not unlikely that, sooner or later, damage to the tissues involved will follow. The ligaments can become elongated or inflamed, which results in pain of chemical origin and also in structural changes. In this new situation, pain will be provoked by stress on structures which have become pathological. It is this progression which produces the dysfunction syndrome, defined as lumbar pain resulting from normal mechanical stress on pathological ligaments (Box 34.2). Postural pain appears when normal ligaments are subjected to abnormal mechanical stresses. This happens with inappropriate spinal loading – poor sitting or prolonged bent positions. Alternatively, abnormal mechanical stresses can originate when, as a result of decreasing intervertebral height, too great a load is applied posteriorly to the spine, a situation which can occur during a particular period in the ageing spine. The loss of turgor in the disc and the decrease in intervertebral space will first allow the posterior ligaments to become lax, causing some postural strain. Further diminution in disc height results in structural changes. At the posterior facets, the joint surfaces override and simulate hyperextension (Fig. 34.1). In this position, considerably more weight falls on the facet joints and the posterior capsule becomes overstretched. Two types of fibre orientation have been described in the capsular fibres of the facet joint.13 Type I capsules have the fibres running diagonally from lateral–caudal to medial– cranial; in type II, the direction is horizontal between the points of insertion on the lower and upper articular processes. Especially in type II, axial loading of the spine results in considerable stretching of the fibres as the upper articular process slides downwards over the lower. Pain may then result. A similar mechanism probably also accounts for ligamentous pain following disc excision and could also explain back pain after chemonucleolysis, which causes a sudden decrease in disc height.14 Continuing degeneration produces a stiff spine because of periarticular fibrosis and enlargement of the facets. As a result, postural pain normally disappears as these changes advance after middle age (see Fig. 34.3 below). The patient is typically young and female, and has diffuse backache, with bilateral radiation over the iliac crests and the sacroiliac joints (Fig. 34.2); pain is never referred below the upper buttocks. When postural pain originates from the sacroiliac ligaments, however, pain reference in the S1 and S2 dermatomes can be encountered (see Ch. 43). The ache usually starts after being in one position for a considerable length of time – sitting or standing – and the intensity of the pain and the duration of the position are related. Barbor8 described postural ligamentous pain as the ‘theatre, cocktail party’ syndrome, because these are characteristic examples of prolonged sitting or standing which produce low back pain. Lying down – for instance, prone – often leads to increased pain, and walking can be painful, especially if the patient is merely strolling slowly. In contrast and surprisingly, to someone who is not familiar with the syndrome, the patient states that during activity and sports he or she is absolutely pain-free. Postural pain (Fig. 34.3) is, as its name implies, a result of positions not movements. Classically, self-treatment and especially prophylaxis are recommended. The patient should be informed about the pain mechanism and taught how to avoid constant static postures. If prolonged sitting is unavoidable, attention should be directed to a proper posture and good choice of furniture. Standing should involve regular movement of the body weight from one leg to the other. All such information and training can be given during a ‘back school’ programme (see p. 588). Contrary to general belief,15 it is unnecessary to give patients with postural back pain a programme of strengthening exercises. Strong muscles will not prevent pain provoked by static mechanical stresses. Chemical sclerosis was used to treat inguinal hernias between the wars and the resulting dense fibrosis of the tissues was noted by Hackett. He adapted the method for the ligamentous periosteal junctions of the posterior lumbar arch as a treatment for chronic low back pain,4 and others followed.16,17 The initial solution used was zinc sulphate and carbolic acid but a bewildering variety of other materials ensued, including various soap derivatives and psyllium seed oil. Not surprisingly, considerable side effects were experienced: three instances of paralysis18,19 and two deaths after injection into the subarachnoid space.20 Dextrose–phenol–glycerol solution, originally developed for the treatment of varicose veins, had a good safety record21 and was introduced into spinal use by Ongley in the late 1950s.10 The mixture provokes an effective inflammatory response, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and new collagen production (O. Troisier, cited by Cyriax22: p. 339). At the periosteal junctions of the ligaments, the fibrosis results in an increase in girth of the ligaments, with contraction and subsequent pain relief. As some of the phenol is injected at or around the medial and lateral branches of the posterior ramus, a direct effect on the nerves may also occur23 and could explain the rapid relief (sometimes from the day or days after the injections) in some patients. In chronic postural backache, the results of these injections are fair. In our experience, about 70% of patients suffering from a postural syndrome become pain-free after 6–8 weeks – the time required to induce sufficient sclerosis. The experience of others is similar.24 Two randomized studies have shown the effectiveness of the treatment in a group of patients suffering from chronic postural low back pain for an average period of 10 years.10,25 Postural syndrome is summarized in Box 34.3. The posterior structures involved are the facet joints, the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, and the iliolumbar ligaments. Disordered muscles are a great rarity, easily distinguished because they are contractile. Ligamentous lesions of the sacroiliac joint will be discussed in Chapter 43. Arthropathy of the facet joints has been regarded as an important source of low back pain for some time. In 1911, Goldthwait maintained that disease of the facet joint was the chief source of backache.26 By 1933, the term ‘facet joint syndrome’ had been introduced.27 In the 1960s and 1970s, the question as to whether back pain could arise from a facet joint problem was vigorously debated in the medical literature.28–30 Opponents of the idea use the following arguments: first, there is no sensory innervation in the synovial tissue of the articular capsule31,32; second, the frequency of grossly disordered joints seen on random radiographs of asymptomatic patients suggests that it is unlikely that minor disorders would cause pain.33 To this end, Cyriax22 listed lesions of the facet joints known to cause no problems: • Gross overriding of the articulating surfaces of the facet joints, occurring as the result of disc resorption in elderly people. • Gross osteoarthritis of the facets, as seen in more than 50% of people above the age of 4534–38; this is an age-dependent and body mass index (BMI)- and gender-independent phenomenon, most frequently observed at two caudal levels, L4–L5 and L5–S1.39 • The angulation that occurs after a wedge fracture of the vertebral body. • Retrolisthesis, when the inferior articular process shifts backwards on the superior articular process of the vertebra below. During the last few decades, however, the balance of the controversy has somewhat tipped towards the conviction that facet joints can be a primary source of low back pain. First, there is an anatomical basis: in contrast to the insensitive synovia, the capsule of the facet joint is richly innervated by nociceptors which become activated when the capsule is stretched or pinched.40 In both pain patients and volunteers, chemical or mechanical stimulation of the facet joints and their nerve supply has been shown to elicit back and/or leg pain.41–43 During spine surgery performed under local anaesthesia, lumbar facet capsule stimulation elicits significant pain in approximately 20% of patients.44 Finally, in a substantial percentage of patients with chronic lower back pain, there is a considerable degree of pain relief after diagnostic injections of the joints with local anaesthetic.45–50 However, some studies have demonstrated extravasation into the epidural space following rupture of the joint capsule if large volumes of anaesthetic agent are used. This may result in an unintentional epidural block, explaining the good diagnostic results.51,52 Each facet joint receives dual innervation from medial branches arising from the posterior primary rami at the same level and one level above.53 However, free nerve endings have been found in the capsule only and not in the articular cartilage or the synovial tissue.11,33 Inflammation could produce pain, as happens during a traumatic arthritis, and it has also been suggested that pain is caused by impingement of a synovial fold between the opposing facets.54,55 Also, inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis, may affect the facet joints.56,57 It is not known if advanced osteoarthrosis as such could be the source of a facet syndrome but it is probable that reduced spinal mobility can sometimes predispose to a sprain of the fibrous capsule.58 In degenerative spondylolisthesis, a disorder that causes the whole upper vertebra, including the neural arch and processes, to slip relative to the lower vertebra, the capsules of the facet joints come under permanent traction. This may account for the increased incidence of backache seen in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.59 A sprain may also follow excessive strain directly on the posterior arch, which sometimes happens as the result of an unintentional twist, usually in extension. Extension of the lumbar spine may be limited by impaction of the inferior articular process on the lamina below. If that happens on one side only, continued application of the extension movement will force the segment towards rotation around the impacted articular process, which draws the inferior articular process of the contralateral facet joint further backwards.60 This may result in sprain of the capsule.61

The ligamentous concept

Introduction

Mechanism of ligamentous pain

Postural syndrome

Dysfunction syndrome

Postural syndrome

Postural pain in the ageing spine

History

Treatment

Posterior dysfunction syndrome

Facet joints

Potential causes of the ‘facet joint syndrome’

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The ligamentous concept