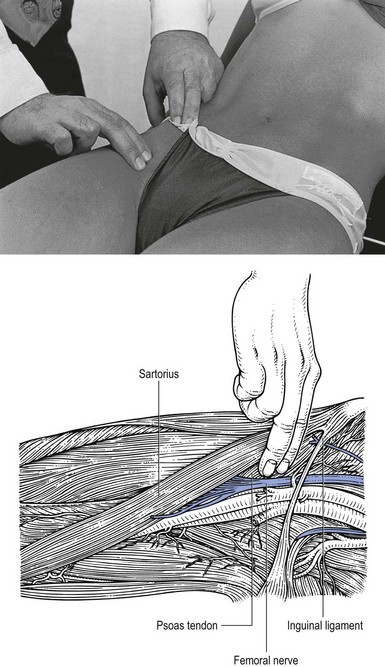

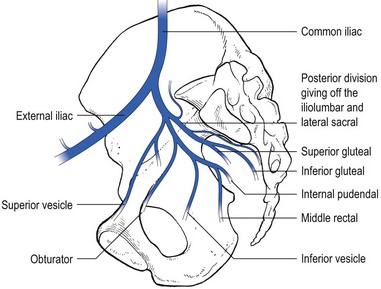

48 Pain in the groin more often results from a tendinous or muscular lesion. It is good to remember, however, that groin pain may also result from a lesion of the lumbar spine, the hip joint or, uncommonly, the sacroiliac joint. Also, a number of intra-abdominal pathological conditions, such as appendicitis, gynaecological disorders and inguinal or femoral hernia, may cause groin pain (see online chapter Groin pain).1 Tendinitis of the psoas is rare. It may result from an acute hyperextension of the hip or from an overuse injury.2–6 Iliopsoas impingement is also an uncommon cause of pain after total hip replacement.7 The lesion is always located in the femoral triangle and thus accessible to the palpating finger. It can be identified just below the inguinal ligament between the pulsating femoral artery medially and the sartorius muscle laterally. Deep transverse friction is very effective.8 Sonography-guided iliopsoas peritendinous injections with steroid have also been proposed as a safe and effective method of treatment.9 The patient sits upright on the couch with the hip joint in 90° of flexion and the knees extended – with the hip extended in the supine position, it is not possible for the finger to penetrate deeply enough because of the taut overlying tissues. The therapist sits at the patient’s side facing the thigh, with the index and middle fingers placed at the painful tendon in the femoral triangle, just lateral to the femoral artery and medial to the sartorius muscle. The thumb is placed at the outer part of the hip and used as a fulcrum (Fig. 48.1). The transverse movement of friction is imparted by alternating flexion and extension of the wrist and elbow, together with some adduction–abduction movement at the shoulder. In acute cases, treatment can be started the day after onset. However, really deep friction should not last more than 1 minute and is repeated daily, with a gradual increase in the treatment time. In the second week, treatment is performed on alternate days. It is then carried out deeply throughout and for about 15 minutes. A good result is to be expected in 2 weeks. Chronic strain requires 15 minutes of friction, two or three times weekly, depending on the result of each session. A lesion that has persisted for years will respond to 6–8 sessions of deep transverse friction. Treatment is very painful but, in our opinion, there is no alternative. Finding the exact point is not easy and requires a good understanding of local topographical anatomy. Resisted flexion is painful, especially if the test is executed with an extended knee (active straight leg raising). Resisted extension of the knee in prone lying position is also painful. The lesion is discussed in ‘Pain on resisted extension of the knee’ (see Ch. 54). In young athletes (aged 15–18) who are skeletally immature, an avulsion fracture of the anterior superior spine of the ilium is more common than a muscle strain or tendinitis (see ‘Pain and weakness’).10 This lesion is principally found in thin, elderly women, often with a history of recent weight loss, obstipation or chronic respiratory disease. The patient complains of numbness or pins and needles, which may eventually culminate in intense pain at the anterior and medial side of the thigh down to the knee. These symptoms result from compression of the obturator nerve at the obturator foramen by a prolapsed fold of peritoneum. Absence of the adductor reflex test is a sign of involvement of motor conduction of the same nerve.11 Pain on resisted hip flexion is explained by pressure exerted by the psoas on the hernia. The differential diagnosis can be made when resisted flexion becomes negative after the patient has been in the Trendelenburg position for upwards of 2 minutes; the effect of gravity is to reduce the prolapse, which is no longer painfully squeezed during active contraction of the psoas. Pain and weakness on resisted flexion can be present in the following conditions. The lesion is well known in young sprinters, soccer players and jumpers.12 While running, the subject feels a sudden painful click in the groin and upper part of the thigh. From that moment further activity is impossible and the athlete leaves the track with a limp; even walking is painful.13,14 On examination, resisted flexion and resisted lateral rotation of the hip and resisted flexion of the knee are all painful. Palpation reveals ecchymosis and palpable tenderness at the anterior superior iliac spine where the sartorius muscle is attached. Radiography shows slight separation of the iliac spine. Spontaneous recovery is the rule and takes 2–3 weeks. During this period, however, total bed rest is not necessary. Movement should be permitted to the limits of pain but return to sports activity should be allowed only from the time that clinical examination becomes fully negative. This may be seen in schoolboys and young athletes. There is no history of sudden onset because the lesion appears to be caused by overuse.15 The complaint is of groin pain during walking. Clinical examination shows a normal range of passive movement but resisted flexion is weak and provokes pain. This should be reason enough to obtain a radiograph, which shows separation at the lesser trochanter. In most instances 2 or 3 weeks’ bed rest in a half-sitting position will be enough for recovery to take place. Once the patient can walk without pain, standing is allowed. It is important to remember that avulsion fractures of the lesser trochanter in adults are almost always the result of metastatic bone disease.16 Weakness of hip flexion is also a common finding in psychoneurotic patients complaining of pain in the lower back or thigh. The diagnosis can only be made if this sign is accompanied by other inconsistencies in the history and clinical examination (see online chapter Psychogenic pain). If there is hamstring tendinitis or sprain of the sacrotuberous ligament, resisted flexion of the knee is then also painful (see ‘Resisted flexion of the knee’, p. 658). An inflamed gluteal bursa is a much more frequent cause of pain on resisted extension, especially if one or more passive movements also elicit the pain (see ‘Gluteal bursitis’, p. 646). Claudication is the symptomatic expression of peripheral artery disease in the leg. It is confined as pain (aching, heaviness, cramping or burning) that is produced with a similar level of walking, disappears after several minutes of standing and occurs at the same distance once walking has resumed.17 Classically, it appears in the calf and/or thigh, but sometimes is confined to the buttock region only and is then caused by a proximal arterial stenosis (bifurcation of the aorta, common iliac, internal iliac and gluteal arteries).18 The essential history is that of a buttock pain that forces the patient to stop walking, improves in a minute or two and reappears when the patient starts walking again. The routine clinical examination is completely negative. An additional test – active extension of the hip in prone-lying position – may reproduce the buttock pain (see p. 625). The usual reduction in femoral pulse may be absent if the stenosis is located on the hypogastric or gluteal artery and there is no substantial damage to the aorta–iliac axis.19 Arterial stenosis is confirmed by Doppler ultrasound or arteriography (Fig. 48.2).20 Pain on resisted adduction that is localized to the groin usually points to the adductors. While the adductor longus, adductor magnus, adductor brevis and pectineal muscles are all adductors of the hip, of these the adductor longus is most often injured in sports.2,21–24 The mechanism of an acute injury is usually that of a sharp cutting movement, which causes a forceful eccentric contraction of the muscle. Acute lesions are common in soccer players and often result from a sudden slip on a muddy field, which stretches or tears the muscle or tendon fibres.25 Alternatively, the lesion starts as an overuse phenomenon, such as repetitive abduction and adduction movements of the leg in the skating stride or in defence movements in basketball. It also occurs in high-jumping athletes and ballet dancers26 and has been described in middle-aged cricket bowlers and ice-hockey players.27,28 Lastly, it is a well-known lesion (‘rider’s sprain’) in horse sports. Pain is provoked mainly on resisted adduction but full passive abduction may also hurt because it stretches the injured muscle fibres.29 Imaging procedures are usually unnecessary. However, ultrasound, although operator-dependent, can confirm the diagnosis.30 There are three possible locations of the lesion: Although pain in the groin during resisted adduction usually indicates a lesion of the adductor longus, this is not always so. Strong adduction indirectly pulls on bones and ligaments of the pelvic ring and, if a pathological condition is present in this region, the transmitted stress causes pain. A detailed discussion of pubic lesions can be found in the online chapter, Groin pain. The following three lesions are the most important.

Disorders of the contractile structures

Resisted flexion

Pain

Tendinitis of the psoas

Treatment

Deep friction

Tendinitis of the rectus femoris

Lesions of the sartorius

Obturator hernia

Pain and weakness

Avulsion fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine

Avulsion fracture at the apophysis of the lesser trochanter

Painless weakness

Psychoneurosis

Resisted extension

Pain

Inflamed gluteal bursa

Buttock claudication

Resisted adduction

Pain

Adductor longus

Differential diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree