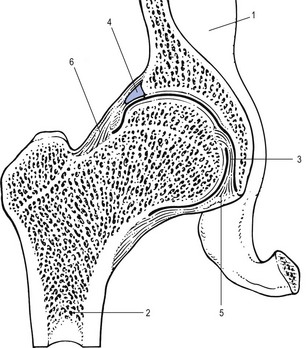

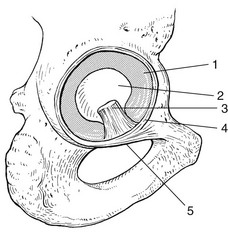

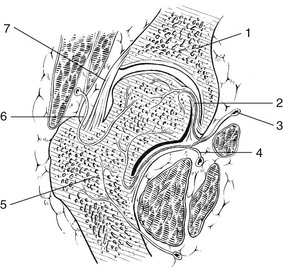

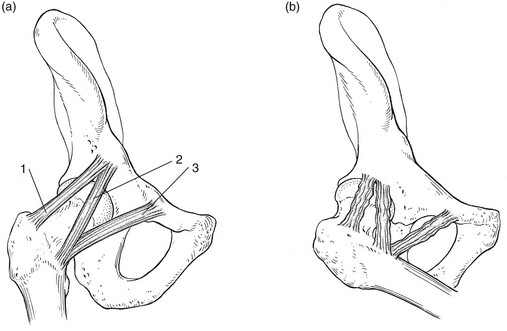

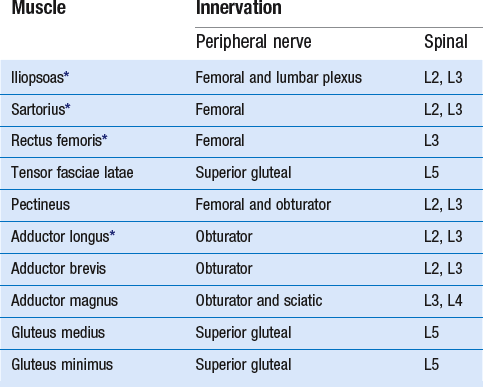

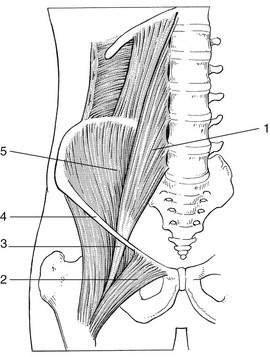

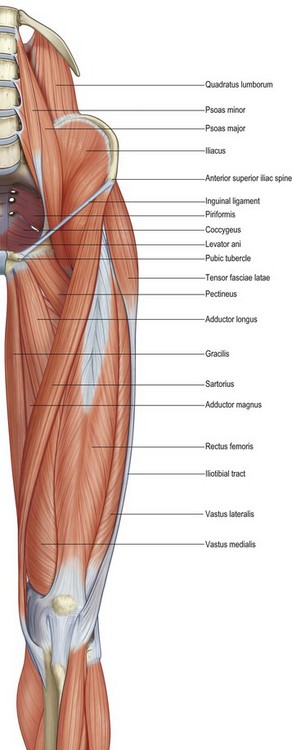

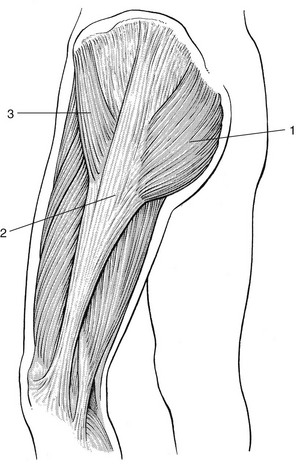

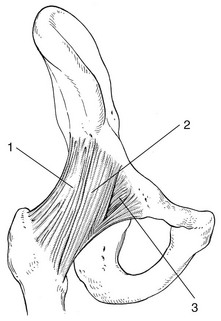

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint, formed by the femoral head and the acetabulum (Fig. 1, see Standring, Fig. 80.15). The articular surfaces are spherical with a marked congruity; this limits the range of movement but contributes to the considerable stability of the joint. In the anatomical position, the anterior/superior part of the femoral head is not covered by the acetabulum. This is because the axes of the femoral head and of the acetabulum are not in line with each other. The axis of the femoral head points superiorly, medially and anteriorly, while the axis of the acetabulum is directed inferiorly, laterally and anteriorly. The cup-shaped acetabulum is a little below the middle third of the inguinal ligament. The acetabular articular surface is an incomplete cartilaginous ring, thickest and broadest above, where the pressure of body weight falls in the erect posture, narrowest in the pubic region. The rough lower part of the cup, the acetabular notch, is not covered by cartilage. The centre of the cup, the acetabular fossa, is also devoid of cartilage but contains fibroelastic fat. The acetabular labrum, a fibrocartilaginous ring attached to the acetabular rim, deepens the cup and enlarges the contact area with the femoral head (see Standring, Fig. 81.5). The part of the labrum that bridges the acetabular notch does not have cartilage cells and is called the transverse acetabular ligament. If forms a foramen through which vessels and nerves may enter the joint. The acetabular labrum is triangular in section. The base is attached to the acetabular rim and the apex is free. The femoral head is ovoid or spheroid but not completely congruent with the reciprocal acetabulum. It is covered by articular cartilage except for a rough pit for the ligamentum teres, a flattened fibrous band, embedded in adipose tissue and lined by the synovial membrane (Figs 2, 3). The ligament connects the central part of the femoral head with the acetabular notch and its transverse acetabular ligament. The ligament is extra-articular and contains a tiny branch of the obturator artery partly responsible for the vascular supply of the femoral head. The femoral head and neck also receive arterial supply from the capsular vessels, arising from the medial and lateral circumflex arteries (see Fig. 3). Anteriorly these are two ligaments: the fan-shaped iliofemoral ligament of Bertin situated craniolaterally; and the pubofemoral ligament, in a more caudomedial orientation. Together they resemble the letter Z (Fig. 4). Posteriorly the capsule is strengthened by the ischiofemoral ligament (see Standring, Fig. 81.3). These three ligaments are coiled round the femoral neck. Extension ‘winds up’ and tautens the ligaments, thus stabilizing the joint passively (Fig. 5a); flexion slackens them (Fig. 5b). Lateral rotation tightens the iliofemoral ligament and also the pubofemoral ligament. Medial rotation tightens the ischiofemoral ligament. Abduction tightens the pubofemoral and the ischiofemoral ligaments. Adduction tightens the lateral part of the iliofemoral ligament. Fig 4 Anterior ligaments: 1, iliofemoral, lateral part; 2, iliofemoral, medial part; 3, pubofemoral. The flexor muscles of the hip joint (Table 1) are anterior to the axis of flexion and extension. The iliopsoas is the most powerful of the flexors (Fig. 6). It originates at the lumbar vertebrae and the corresponding intervertebral discs of the last thoracic and all the lumbar vertebrae, the superior two-thirds of the bony iliac fossa and the iliolumbar and ventral sacroiliac ligaments. The insertion is to the lesser trochanter. Although its main function is flexion, it is also a weak adductor and lateral rotator. The distal part of the muscle is palpable just deep to the inguinal ligament, where it lies bordered by the sartorius muscle laterally and the femoral artery medially (Fig. 7). The sartorius is mainly a flexor of the hip, originating at the anterior superior iliac spine and inserting at the proximal part of the medial surface of the tibia (see Fig. 7). Consequently the muscle acts on two joints, with the accessory function of lateral rotation and abduction of the hip as well as flexion and medial rotation of the knee. At the surface, the muscle divides the anterior aspect of the thigh into a medial and a lateral femoral triangle. During active flexion, abduction and lateral rotation at the hip and 90° flexion at the knee, the muscle becomes prominent and is easily palpable. The rectus femoris combines movements of flexion at the hip and extension at the knee. Its origin is at the anterior inferior iliac spine, a groove above the acetabulum and the fibrous capsule of the hip joint and inserts into the common quadriceps tendon at the proximal border of the patella (see Fig. 7). The origin can be palpated only in a sitting position because of tension in the overlying structures. The tendon and muscle belly are bordered medially by the sartorius muscle, and laterally by the tensor fasciae latae and the vastus lateralis, the largest part of the quadriceps. The tensor fasciae latae (see Fig. 7) originates at the outer surface of the anterior superior iliac spine, and inserts into the proximal part of the iliotibial tract – a strong band which thickens the fascia lata at its lateral aspect. Thus the course of the tensor is dorsal and distal. Acting through the iliotibial tract the muscle extends and rotates the knee laterally. It may also assist in flexion, abduction and medial rotation of the hip. In the erect posture, it helps to steady the pelvis on the head of the femur (Fig. 8). The muscle can be palpated easily during resisted flexion and abduction of the hip with the knee extended.

Applied anatomy of the hip and buttock

The hip joint

Capsule and ligaments

Muscles

Flexor muscles

anatomy of the hip and buttock