, George C. Babis2 and Kalliopi Lampropoulou-Adamidou3

(1)

Orthopaedic Department Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University, Athens, Greece

(2)

2nd Orthopaedic Department Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University Nea Ionia General Hospital “Konstantopoulion”, Athens, Greece

(3)

3rd Orthopaedic Department, National and Kapodistrian University KAT General Hospital, Athens, Greece

Abstract

In this introductory chapter, basic anatomic information is presented regarding the osseous structures of the hip joint.

The joint of the hip develops from the cartilaginous anlage at 4–6 weeks of the embryonic development. At 7 weeks of gestation, a cleft develops between pre-cartilaginous cells defining the femoral head and acetabulum, and at 11 weeks, the hip joint formation is complete. Then, the femoral head is encircled by the acetabulum and it is difficult to dislocate [1].

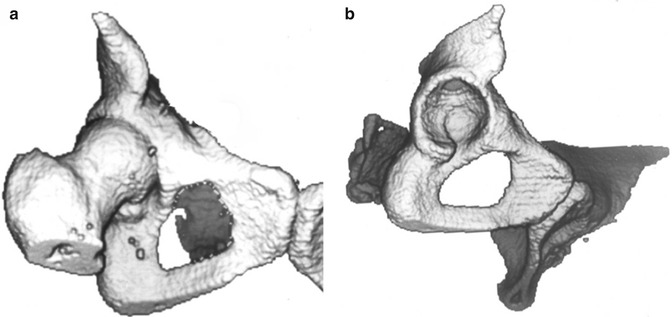

The hip is the biggest and more stable joint in the human body. It is formed from the femoral head and a deep cavity, with raised bone margins, the acetabulum (Figs. 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3). It is a typical ball-and-socket joint. The depth of the acetabulum increased by the fibrocartilaginous labrum which is attached circumferentially to the bony rim providing 170° coverage of the femoral head. The bony rim of the acetabulum is interrupted at its lower part to form the acetabular notch , which is then bridged by the extension of the labrum, the transverse ligament . The acetabular branch of the obturator artery passes under the transverse ligament to enter the ligamentum teres . The inferior part of the acetabulum is referred to as acetabular fossa , being the thinnest part of the acetabular floor. The laminate-shaped articular cartilage of the acetabulum covers its periphery, while acetabular fossa remains without cartilage. The head of the femur, that forms two-thirds of a sphere, is covered by articular cartilage, except of the fossa for the attachment of ligamentum teres.