, George C. Babis2 and Kalliopi Lampropoulou-Adamidou3

(1)

Orthopaedic Department Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University, Athens, Greece

(2)

2nd Orthopaedic Department Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University Nea Ionia General Hospital “Konstantopoulion”, Athens, Greece

(3)

3rd Orthopaedic Department, National and Kapodistrian University KAT General Hospital, Athens, Greece

Abstract

Orthopaedic surgeons, specialising in adult hip reconstruction surgery, often face the problem of osteoarthritis secondary to congenital hip disease. For better communication, treatment planning and evaluation of the results of various treatment options, an agreed term is needed to cover the entire pathology, and furthermore, a generally accepted classification is necessary. The authors prefer, as it is described in the present chapter, the use of the term “congenital hip disease” and the classification in dysplasia, low dislocation and high dislocation. In dysplasia, the femoral head is contained within the original acetabulum, in low dislocation the femoral head articulates with a false acetabulum that partially covers the true acetabulum, and in high dislocation the femoral head has migrated superoposteriorly. Acetabular deformities and deficiencies, found in these three types, also differ.

3.1 General Aspects

The use of ultrasound as a screening test in the newborn has allowed earlier diagnosis and treatment, with a better prognosis, for congenital hip disease (CHD) [1]. However, orthopaedic surgeons who specialise in adult reconstruction surgery often face the problem of osteoarthritis (OA) secondary to CHD in adult patients. These cases could be of different severity and are usually the result of late diagnosis and treatment in areas where early screening and treatment were not effective or in patients in whom treatment had failed in childhood [2].

Congenital disease is the main cause of secondary OA of the hip (Fig. 3.1). Other causes such as osteochondritis (Fig. 3.2) and slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) (Fig. 3.3) are much less common. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) has also been considered as a cause of early OA (Fig. 2.7). However, there is no clinical confirmation to support this hypothesis [3, 4].

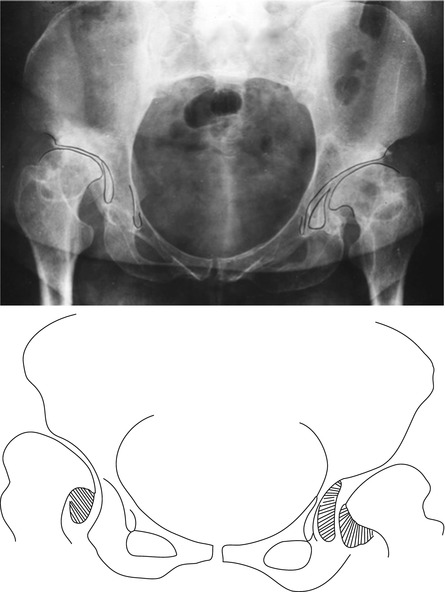

Fig. 3.1

A 30-year-old female with bilateral secondary OA due to CHD

Fig. 3.2

A 32-year-old male with secondary OA of the right hip due to osteochondritis

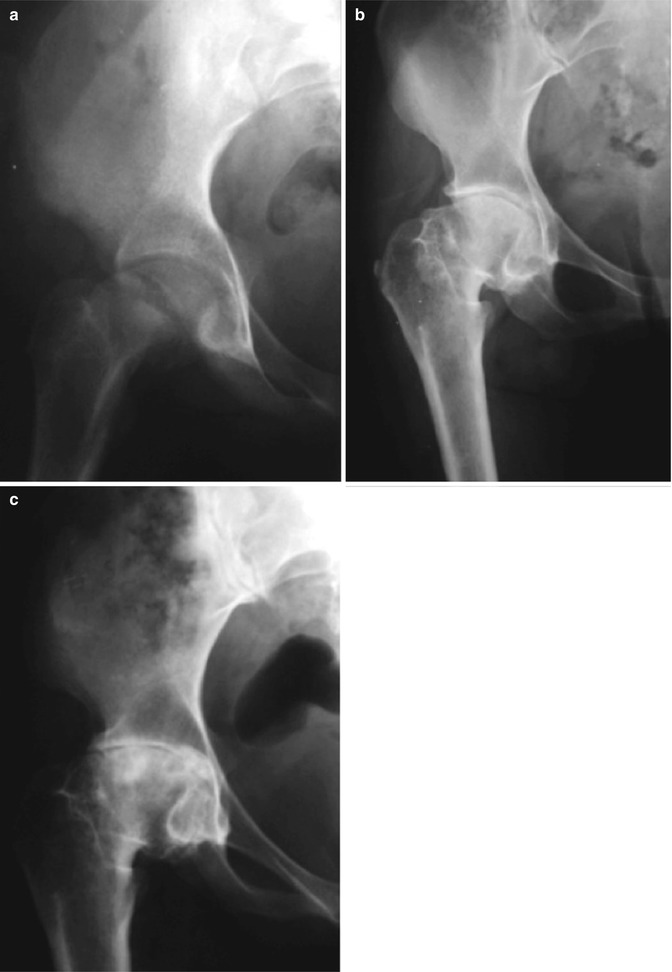

Fig. 3.3

Female patient with a chronic slipped capital epiphysis treated with a subtrochanteric osteotomy at the age of 12. (a) Preoperative radiograph. (b) Radiograph taken when the patient was 31 years old. She was slightly limping without pain. (c) At the age of 37, patient had developed secondary OA. She had severe pain and was heavily limping

Hip pain and limping are the cardinal symptoms leading young adults with secondary OA due to CHD to the specialised surgeons. Often, patients’ complaints include early fatigue and pain in the back and/or the knees.

Before the introduction of total hip replacement (THR), patients with CHD were doomed to disability during all their lives. Femoral and pelvic osteotomies had limited indications and short-term satisfactory results (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5). The introduction of THR, the revolutionary operation of the past century, radically improved the quality of life of these patients, especially of young females with severe types of CHD, presenting a special group of patients with problematic life since birth. Apart from their young age, these patients have several psychological disorders, as anxiety and depression, since their early childhood. Having been born and raised with this deformity in an able-bodied privileged society have had their lives affected in a fundamental way. In addition to experiences of multiple and prolonged treatments in early childhood, these patients describe traumatic experiences, especially during their developmental years, impacting them socially, mentally and emotionally. Treatment with THR makes the change in quality of their life much more dramatic. It is of particular interest, how some patients describe certain life experiences after surgery: “I felt that I was born again”, “I see myself in the mirror and I don’t believe my eyes”, “Men started paying attention to me”, “Some people talk about a miracle”, “I work, travel, I have fun without a concern about my hips problem”, “I developed faith in myself” (see more details in Chap. 11). Even patients who underwent several revisions had enjoyed life free of pain with function improvement for a reasonable period of time [5].

Fig. 3.4

This patient at the age of 17, in 1962, had a Schanz subtrochanteric osteotomy, which caused great technical difficulties when patient came for hip replacement, 15 years later

Fig. 3.5

A 42-year-old female with advanced secondary OA of the hip due to CHD. At the age of 31, in 1970, she had a McMurray subtrochanteric osteotomy with no clear indications

Orthopaedic surgeons who treat adult patients with CHD should be familiar with its terminology and be able to recognise the anatomical abnormalities. Most importantly to know the absolute indications for THR , carry out through preoperative planning, reconstruct the hip using the appropriate surgical technique and implants and finally be able to anticipate the clinical outcome and avoid complications.

This volume aims to provide the surgeons concerned with CHD with relevant information based mainly on the authors’ experience.

3.2 Terminology

For better communication, treatment planning and evaluation of results of different treatments, there is a need for an agreed terminology, which covers the entire spectrum of congenital deformities of the hip.

The congenital nature of the disease has been recognised, even before availability of radiographs, when Dupuytren [6], in 1826, observed some newborn infants with displacement of the head of the femur from the acetabulum. He named this condition “congenital displacement ”. Dupuytren’s recognition of the congenital nature of the deformity has been accepted as original. In 1897, Phelps [7], based on anatomical specimens, also considered that the majority of such cases are really dislocations at birth. Since that time, in many other pioneer works with anatomical dissections and studies of the pathologic features at open operations, the authors had accepted the congenital nature of the deformity [8–13].

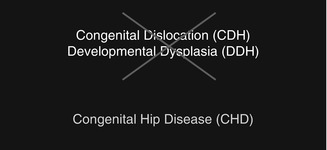

The term “congenital displacement” proposed by Dupuytren was slightly modified to “congenital dislocation of the hip ”, a term that dominated among orthopaedics, paediatricians and other physicians for decades. However, it was later recognised that the use of this term led to considerable confusion in understanding the underlying deformities and in communication between physicians, and its accuracy became questionable. The congenital nature of the deformity has not been disputed by the majority of authors, but it was recognised that variable pathologies that existed at birth and progressed in adult life were not necessarily dislocations. During the following years the literature on the pathogenesis and terminology of congenital dislocation of the hip were replete with contradictions and uncertainties. In 1989, in his brief report, Klisic emphasised that congenital dislocation is a misleading term, when used for the total spectrum of the deformity [14]. Instead, he recommended the use of the term “developmental displacement ”. Though many authors and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons accepted the change in wording of congenital to developmental, on the other hand, they replaced the wording of displacement, proposed by Klisic, with that of dysplasia, and a new term “developmental dysplasia of the hip ” was established. Nonetheless, despite the latest effort for an appropriate definition covering the total spectrum of the disease, inaccuracies still persist, reflecting mainly the confusion as to the original cause. Specifically, the term developmental is not descriptive of the congenital nature of the deformity, while an indiscriminate use of the term dysplasia does not reflect the variety of underlying pathology. Thus, unfortunately, from a deficient term “congenital dislocation”, we ended up with a non-specific and unsuitable one “developmental dysplasia of the hip”, without convincing arguments for the change. Developmental has the meaning of evolving, gradually changing and progressing. However, in this case, the disorder is congenital in origin – the primary abnormality originates in utero and developmental in nature, which is a dynamic process. On the other hand, the term “dysplasia”, a mixed Greek word, composed by the word “bad” and “form”, can be reserved for the mildest types of hip deformities, in contrast to the most severe types of hip dislocations, avoiding confusion and diagnostic inaccuracies [15] (Fig. 3.6). Furthermore, the term “subluxation ”, used for the description of infant hips , should not be used in adults, because this simply refers to the degree of the displacement of the femoral head, without defining anatomical abnormalities at the site (Fig. 3.7).

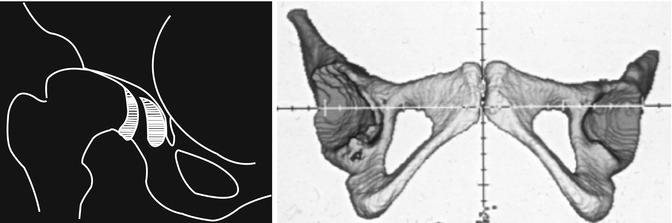

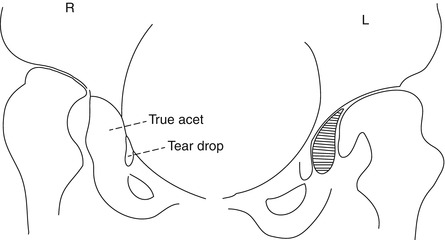

Fig. 3.6

By using the term “dysplasia”, for both these hips, inaccuracy of description is obvious. Note that the right femoral head articulates with a false acetabulum, and the left with the true acetabulum

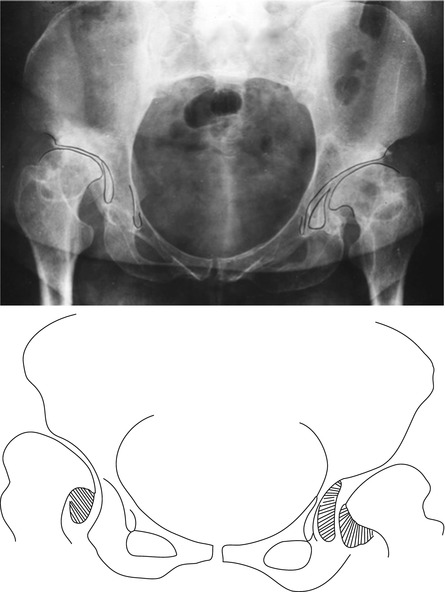

Fig. 3.7

Right and left hip show almost the same degree of subluxation of the femoral head. However, the underlying anatomical abnormalities differ

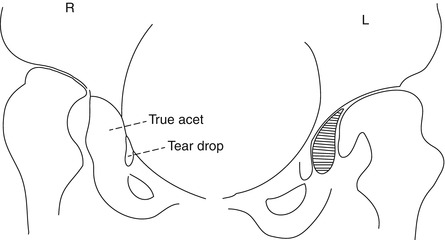

Authors’ suggestion is to use the term “congenital hip disease” for the entire spectrum of the deformities (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.8

Congenital hip disease is the term suggested by the authors

3.3 Classification

An internationally accepted classification system improves communication, planning of treatment and comparison of results of different treatments, by avoiding inclusion of dissimilar cases within the same series. For a classification system to be useful in clinical practice, it should be accurate, precisely describing the underlying pathological anatomy, simple and easy to memorise. Several classification systems have been used to describe the different types of congenital hip disease (CHD) in adults. The most commonly used are those of Crowe et al. [16] and Hartofilakidis et al. [17, 18]. Other classification systems are those by Eftekhar [19] and Kerboull [20] (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

Details of classification systems for congenital hip disease

Author(s) | Hartofilakidis et al. | Crowe et al. | Eftekhar | Kerboull |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Types of increasingseverity | Dysplasia | I, <50 % | Dysplasia | Anterior |

II, 50–75 % | ||||

Low dislocation B1 | III, 75–100 % | Intermediatedislocation | Intermediate | |

Low dislocation B2 | ||||

High dislocation C1 | IV, >100 % | High dislocation | Posterior | |

High dislocation C2 | Old unreduceddislocation | |||

Characteristicfeatures | Description of anatomicalabnormalities | Proximal migration/height of femoral head | Degree ofsubluxation | Direction of subluxation |

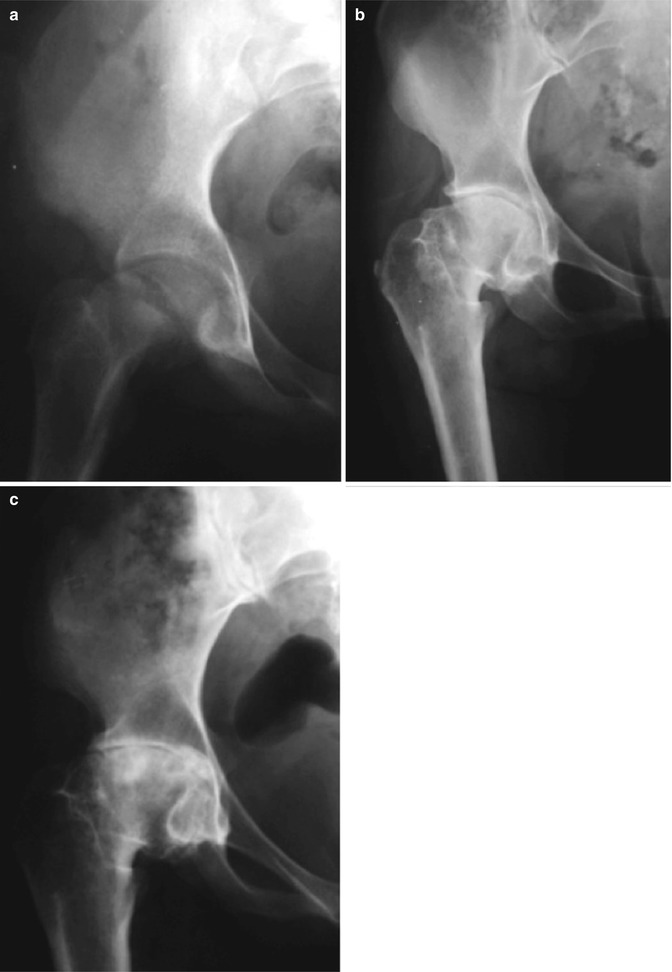

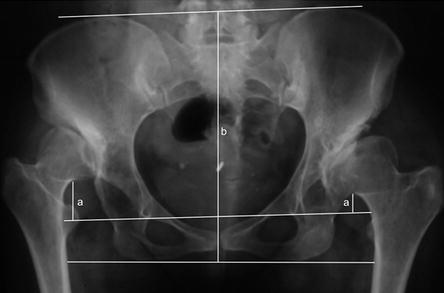

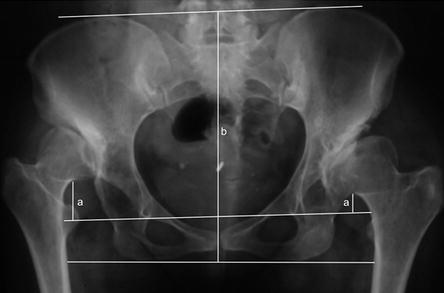

Crowe et al. classification is based on three anatomical landmarks, identified in a whole pelvis radiograph (Fig. 3.9): (1) the height of the pelvis, (2) the medial head-neck junction and (3) the lower part of the teardrop.

Fig. 3.9

The Crowe classification relies on the percentage of the height of the dislocation (a) in relation to the height of the pelvis (b)

The vertical distance between the reference interteardrop line and the head-neck junction indicates the degree of subluxation (proximal migration of the femoral head), and the one between the line connecting the ischial tuberosities and the iliac crests indicates the height of the pelvis. Four types of dislocation are described according to the a/b value: type I, when proximal migration of the femoral head is less than 10 % of pelvic height (a/b < 0.1); type II, when it is 10–15 % 0.1 < a/b < 0.15; type III, 15–20 % 0.15 < a/b < 0.2; and type IV, when it is more than 20 % (a/b > 0.2).

Hartofilakidis et al. classification , based on radiographic and intraoperative criteria, recognises three main types of increasing severity (Figs. 3.10, 3.11, 3.12 and 3.13): dysplasia (type A), in which the femoral head articulates with the true acetabulum, despite the degree of subluxation; low dislocation (type B), in which the femoral head articulates with a false acetabulum that partially covers the true acetabulum to a varying degree; and high dislocation (type C), where the femoral head has migrated superiorly and posteriorly in relation to the true acetabulum and may articulate with a hollow in the iliac wing, which resembles a false acetabulum, or move freely within the gluteal muscles [17, 18].