Chapter 1 The Family Physician

The curriculum for training family physicians is designed to represent realistically the skills and body of knowledge that the physicians will require in practice. This curriculum is based on an analysis of the problems seen and the skills used by family physicians in their practice. The randomly educated primary physician has been replaced by one specifically prepared to address the types of problems likely to be encountered in practice. For this reason, the “model office” is an essential component of all family practice residency programs.

The Joy of Family Practice

The rewards in family medicine come largely from knowing patients intimately over time and sharing their trust, respect, and friendship. The thrill is the close bond (friendship) that develops with patients. This bond is strengthened with each physical or emotional crisis in a person’s life, when he or she turns to the family physician for help. It is a pleasure going to the office every day and a privilege to work closely with people who value and respect our efforts.

Patient Satisfaction

Attributes considered most important for patient satisfaction are listed in Table 1-1 (Stock Keister et al., 2004a). Overall, people want their primary care doctor to meet five basic criteria: “to be in their insurance plan, to be in a location that is convenient, to be able to schedule an appointment within a reasonable period of time, to have good communication skills, and to have a reasonable amount of experience in practice.” They especially want “a physician who listens to them, who takes the time to explain things to them, and who is able to effectively integrate their care” (Stock Keister et al., 2004b, p. 2312).

Table 1-1 What Patients Want in a Physician

Modified from Stock Keister MC, Green LA, Kahn NB, et al. What people want from their family physician. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:2310.

Development of the Specialty

Dr. Peabody’s declaration proved to be premature; neither the medical establishment nor society was ready for such a proclamation. The trend toward specialization gained momentum through the 1950s, and fewer physicians entered general practice. In the early 1960s, leaders in the field of general practice began advocating a seemingly paradoxical solution to reverse the trend and correct the scarcity of general practitioners—the creation of still another specialty. These physicians envisioned a specialty that embodied the knowledge, skills, and ideals they knew as primary care. In 1966 the concept of a new specialty in primary care received official recognition in two separate reports published 1 month apart. The first was the report of the Citizens’ Commission on Medical Education of the American Medical Association, also known as the Millis Commission Report. The second report came from the Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council of Medical Education of the American Medical Association, also called the Willard Committee (1966). Three years later, in 1969, the American Board of Family Practice (ABFP) became the 20th medical specialty board. The name of the specialty board was changed in 2004 to the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM).

Definitions

Primary Care

Primary care is the backbone of the health care system and encompasses the following functions:

Personalized Care

In the 12th century, Maimonides said, “May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain. May I never consider him merely a vessel of disease” (Friedenwald, 1917). If an intimate relationship with patients remains the primary concern of physicians, high-quality medical care will persist, regardless of the way it is organized and financed. For this reason, family medicine emphasizes consideration of the individual patient in the full context of her or his life, rather than the episodic care of a presenting complaint.

Ludmerer (1999a) focused on the problems facing medical education in this environment:

Some managed care organizations have even urged that physicians be taught to act in part as advocates of the insurance payer rather than the patients for whom they care (p. 881)…. Medical educators would do well to ponder the potential long-term consequences of educating the nation’s physicians in today’s commercial atmosphere in which the good visit is a short visit, patients are “consumers,” and institutional officials speak more often of the financial balance sheet than of service and the relief of patients’ suffering (p. 882).

Cranshaw and colleagues (1995) discussed the ethics of the medical profession:

Caring

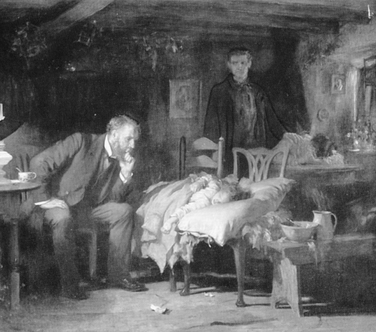

Family physicians do not just treat patients; they care for people. This caring function of family medicine emphasizes the personalized approach to understanding the patient as a person, respecting the person as an individual, and showing compassion for his or her discomfort. The best illustration of a caring and compassionate physician is “The Doctor” by Sir Luke Fildes (Figure 1-1). The painting shows a physician at the bedside of an ill child in the preantibiotic era. The physician in the painting is Dr. Murray, who cared for Sir Luke Fildes’s son, who died Christmas morning 1877. The painting has become the symbol for medicine as a caring profession.

Compassion

Compassion means co-suffering and reflects the physician’s willingness somehow to share the patient’s anguish and understand what the sickness means to that person. Compassion is an attempt to feel along with the patient. Pellegrino (1979, p. 161) said, “We can never feel with another person when we pass judgment as a superior, only when we see our own frailties as well as his.” A compassionate authority figure is effective only when others can receive the “orders” without being humiliated. The physician must not “put down” the patients, but must be ever ready, in Galileo’s words, “to pronounce that wise, ingenuous, and modest statement—‘I don’t know.’” Compassion, practiced in these terms in each patient encounter, obtunds the inherent dehumanizing tendencies of the current highly institutionalized and technologically oriented patterns of patient care.

Characteristics and Functions of the Family Physician

The ideal family physician is an explorer, driven by a persistent curiosity and the desire to know more (Table 1-2).

Table 1-2 Attributes of the Family Physician∗