12. The cognitive behavioural frame of reference

Edward A.S. Duncan

Overview

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a popular and evidence-based psychotherapeutic approach. Whilst its guiding principles are associated with ancient Greek thought, current developments emanate from the modern theoretical frameworks of behavioural therapy and cognitive therapy. Contemporary CBT represents a broad church of theoretical developments, interventions and professional groupings (British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies 2003).

This chapter outlines the development and general principles of CBT. It continues by examining CBT’s theoretical framework and general characteristics. Having provided an overview of CBT in general, the chapter explores the various uses of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference in occupational therapy. In doing so, the criticisms that have been made of occupational therapists’ use of CBT to date are acknowledged and proposals for ways in which the strengths of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference can be integrated within occupationally focused practice are offered.

This chapter:

• provides an accessible overview of the historical development of CBT

• outlines a cognitive behavioural frame of reference in occupational therapy

• presents criticisms of the use of CBT in occupational therapy

• illustrates how a cognitive behavioural approach can be integrated within occupational therapy practice.

Introduction

‘Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the term given to a specific psychological approach to conceptualizing and addressing clients’ difficulties’ (Duncan 2003a). Whilst CBT is frequently associated with the work of psychologists, it is more accurately described as a shared intervention by a variety of health professionals.

CBT’s robust and developing evidence base has consistently drawn occupational therapists to use it in practice. However, in doing so, the potential to become a general mental health practitioner and not an occupational therapist has been noted. Considerable debate has taken place regarding the fact that occupational therapists may carry out CBT as a form of psychotherapy. The case for occupational therapists’ use of their shared skills in this respect has been given elsewhere (Duncan, 1999, Duncan, 2003a, Duncan, 2003b, Harrison, 2003 and Stewart, 2003) and will not be repeated here. Distancing from the occupational therapy role is, however, not essential in order for a clinician to use a CBT approach in practice. In fact, the incorporation of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference within occupational therapy is not only achievable but also highly desirable. Therefore, this chapter focuses on the use of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference within an occupational therapy context.

What is CBT?

Historical development

CBT is a dynamic body of knowledge that has developed since the 1950s. It is strongly influenced by the theoretical and therapeutic traditions of behavioural therapy and cognitive therapy. Behavioural therapy, in turn, has been significantly shaped by the evolutionary perspective of health. Its developmental roots stretch back to the beginning of the 20th century, when animal behaviour research was carried out and related to human beings (Hawton et al 1996). Cognitive therapy, whilst developing later than behavioural therapy, claims more historic roots. It cites the Roman emperor Epictetus, who wrote, ‘Men are disturbed, not by things, but of the view they take of them’, as an example of the early recognition of the power of thought on health (Beck et al 1979).

Behavioural therapy

Two principles of animal learning theory have affected the development of behavioural therapy: classical conditioning and operant conditioning (Bernstein 1996). Both classical and operant conditioning are briefly outlined below; however, readers are encouraged to refer to other texts for a more comprehensive overview of these important theories.

Classical conditioning

Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, developed the theory of classical conditioning at the turn of the 20th century. However, the original development of this theory could not have been further from its eventual applied role within behaviour therapy. Classical conditioning was discovered during an experiment into the digestive process of dogs, a study that would win Pavlov the Nobel Prize for Physiology/Medicine in 1904. In 1913, John Watson employed classical conditioning theory in the development of behaviourist theory. Watson’s theory was popular, as it offered an objective and measurable basis for human behaviour, an approach that was in stark contrast to the other predominant psychological theories of the time (Hawton et al., 1996 and Duncan, 2003a).

Operant conditioning

The second influential learning theory in the development of behavioural theory was operant conditioning. This outlines ‘the Law of Effect’, whereby a behaviour that is rewarded will tend to be repeated, and behaviour that is punished will diminish (Hawton et al 1996).

Burrhus F. Skinner, an American psychologist, developed Pavlov’s work by extending the principle of reinforcement. Previously, an action was considered to be reinforced if it increased or decreased behaviour. Skinner explored different types of reinforcers and consequences. It was observed that different types of reinforcers had different effects on behaviour, depending upon the nature of the action. Together, classical and operant conditioning provided the theoretical foundation for a variety of behaviour therapy interventions, mainly in mental health settings (Hawton et al 1996).

Whilst the benefits of behaviour therapy were widely recognized, the late 1960s and early 1970s witnessed a developing disillusionment with behaviour therapy as the theoretical shortcomings and practical failures associated with the approach came into focus. Such disillusionment, at least amongst some, supported the birth of another, related form of therapy known as cognitive therapy.

Cognitive therapy

The original attribution of a cognitive approach to therapy is given to Mechinbaum (1975). However, it is the work of Aaron T. Beck, an American psychiatrist, that has become synonymous with the term cognitive therapy.

‘Aaron Beck (b. 1921) developed cognitive therapy though an examination of the links between the environment, the person and his/her emotion and motivation. Surprisingly, Beck, a medical doctor, did not come from a foundation in behaviorism. Instead, Beck’s theoretical roots were found in the psychoanalytical perspective’ (Duncan 2003a). Beck’s career commenced in psychiatry, and he trained in psychoanalytical theory and practice. Despite initially questioning the nature of psychoanalytical theory, he embraced the approach, even undertaking research aimed at proving the efficacy of the approach in relation to depression. However, this study reignited his initial doubts about psychoanalytical theory and in doing so led to the development of cognitive therapy. Subsequently, Beck has published extensively on the theory and practice of cognitive therapy. For those who are interested in finding out more about Aaron Beck, a biography of his life and work has been published (Weishaar 1993).

Cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy, whilst taking significantly different views about the causal factors of a disorder (i.e. that it has a cognitive or behavioural root), have many commonalities. It was perhaps inevitable, therefore, that both theories became combined into the generally accepted framework of cognitive behavioural therapy.

Conditions in which CBT is commonly used

Owing to its strong evidence base in a variety of contexts (e.g. anxiety, depression and psychosis) (Department of Health 2001) and support in a range of clinical guidelines from both the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), CBT has become an increasingly popular method of intervention and has swiftly developed over the last 20 years. As well as having a strong evidence base for practice in the forenamed conditions, CBT is often associated with interventions to address alcohol abuse (e.g. Longabaugh & Morgenstern 1999), personality disorders (e.g. Young, 1999 and Davidson et al., 2006), family therapy (e.g. Epstein 2003) and drug abuse (e.g. Beck et al 1993, Waldron & Kaminer 2004). As well as conditions traditionally found within the mental health spectrum of interventions, CBT has also been positively associated with various other conditions, including chronic pain (Strong 1998, McCracken and Turk, 2002 and Vlaeyen and Morley, 2005) and chronic fatigue syndrome (Prins et al., 200l and Price et al., 2008).

An introduction to the theoretical framework of CBT

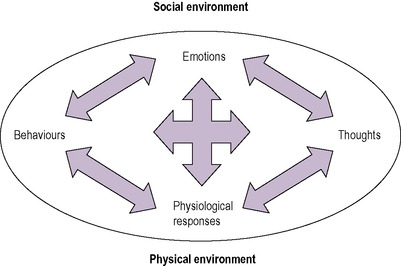

CBT takes a problem-focused perspective of life difficulties and focuses on five aspects of life experience:

• thoughts

• behaviours

• emotion/mood

• physiological responses

• the environment (Greenberger & Padesky 1995).

Each aspect of life experience is influenced by the social and physical environment in which they are placed (Fig. 12.1). CBT suggests that changes in any factor can lead to an improvement or deterioration in the other factors. For example, if we exercise (behaviour), we feel better (mood); if we feel nervous (mood), we may experience an increased heart rate or sweat more (physiological reaction); if we find large social gatherings difficult (social environment), we may avoid them (behaviour).

|

| Fig. 12.1 • The influence of the social and physical environment on aspects of life experience. (Reproduced with the permission of Kathlyn L. Reed.) |

The way in which CBT is delivered depends on the training of the therapist and the needs of the client. In practice, the majority of clinicians using these approaches draw from its richness of technique and theory. However, therapists’ training and personal preferences can lead to a greater emphasis on a cognitive or behavioural approach:

• Cognitive therapy places an emphasis on rapid and automatic interpretations of events and the importance of underlying beliefs and values.

• Behaviour therapy emphasizes our automatic learned responses to stimuli and the way in which our behaviour is shaped by its consequences.

One of the key theoretical components to understanding the theoretical basis of CBT is its postulated levels of cognition.

Levels of cognition

Cognitions are the way in which we know, sense or perceive reality (Chambers 1994) (Box 12.1). Beck et al (1979), in their seminal text, Cognitive Therapy of Depression, outlined three levels of cognition that are amenable to therapeutic intervention. Key to this conceptualization is the idea that, unlike other psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g. psychodynamic psychotherapy), each of these levels is accessible by the client. The levels are hierarchical in nature, with automatic thoughts being the most frequently occurring and easily accessible, beliefs being more constant and core schema representing the building blocks of thought processes and being more challenging to shift.

Box 12.1

Activity

Imagine you are asleep in bed … Suddenly you are awakened by a loud crashing sound from downstairs. How would you feel?

• How would you feel if you knew there had been a spate of violent burglaries in your neighbourhood?

• How would you feel if you had just bought a new kitten that has been knocking over everything in sight?

The nature of feelings is largely determined by the way we think.

Automatic thoughts

Automatic thoughts are habitual and plausible. They are the uninvited thoughts that pop into your head (e.g. ‘I’ll sound stupid if I ask a question in this class’). Everyone has automatic thoughts and it is likely that you will have some whilst reading this chapter (e.g. What am I having for tea? Is this going to help me with my assignment? When am I seeing my next client?). However, for clients, more often than not automatic thoughts will be negative in nature. Another characteristic of automatic thoughts is that they can be situation-specific — a client may be plagued by unhelpful automatic thoughts whilst in a stressful work situation and find it difficult to cope, whilst appearing to function without difficulty when in the home environment.

It is useful to understand the automatic thoughts a client is having, as these can have a direct impact on their presentation in sessions and their ability to carry out day-to-day life activities. Several techniques can be used to elicit automatic thoughts.

• Direct questioning. What is (was) going through your mind just now?

• Inductive questioning. Use a series of open questions and reflexive statements to help a client recall an emotional situation (e.g. What happened next? What did you do?).

• Re-enacting/recreating a situation. Use imagery, role play and in vivo experiments.

• Recording thoughts. Use thought diaries and so on.

Where thoughts are recognized as being unhelpful, the therapist and clinician can work together to help the client to change the nature of their thinking — in the knowledge that this will help their behaviour. Importantly, changing thoughts is not the same as thinking more positively, which is unlikely in itself to lead to improved functioning (Greenberger & Padesky 1995). Challenging automatic thoughts is about gaining a sense of perspective on a situation, taking alternative perspectives and exploring new perspectives and solutions. Methods to challenge thoughts include:

• Looking at the evidence:

○ What do I know about this situation?

○ How well do my thoughts fit the facts?

○ Do I have experiences that suggest my thoughts are not completely true?

○ Would my thoughts be accepted as correct by other people?

• Looking at other possible interpretations:

○ Are there other interpretations that fit the facts just as well?

○ How might a friend think of this situation?

○ How will I think about this in 6 months or a year?

• Looking at the helpfulness of thinking this way:

○ If the facts are bleak, does my way of thinking help?

○ Is this type of thinking likely to make me feel worse?

○ Am I brooding over questions with no clear-cut answers?

○ Am I behaving in ways that may make the situation worse?

Beliefs

These are conditional beliefs that we hold about ourselves. They may be unhelpful in nature (e.g. ‘I always make a fool of myself when I meet my friends in the pub’). Whilst automatic thoughts are often easily accessible, beliefs tend to be slightly less obvious. They can sometimes be inferred from individuals’ actions. If beliefs are to be put into words, then they often take the form of ‘if … then …’ sentences (e.g. If I cannot do my job to perfection, then everyone will think I am a failure’) or of statements that contain ‘should’ (e.g. I should be the life and soul of a party) (Greenberger & Padesky 1995). Conditional beliefs lie beneath and shape the automatic thoughts that pop into our head; they can be viewed as guiding principles that affect our daily life experiences. All lives are governed by beliefs to a certain extent and these in turn govern our behaviour. Some people, however, develop unhelpful beliefs about a range of issues and these can often significantly affect the way in which they lead their lives.

Whilst unhelpful beliefs can be varied in nature, there are several categories in which the most common beliefs can be placed. It is often helpful to discuss these categories with clients to see if any of them resonate with their experience (Box 12.2).

Box 12.2

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Typical forms of unhelpful beliefs

Overgeneralization

• Making sweeping judgements on the basis of single instances. ‘Everything I do goes wrong.’

Selective abstraction

• Attending only to negative aspects of experience. ‘Not one good thing happened today.’

Dichotomous reasoning

• Thinking in extremes, also known as black and white thinking. ‘If I can’t get it right, there’s no point in doing it at all.’

Personalization

• Taking responsibility for things that have little or nothing to do with oneself. ‘I must have done something to offend him.’

Arbitrary influence

• Jumping to conclusions without enough evidence. ‘This course is rubbish’ (when you have only just started it!).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree