14. The biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy

Ian R. McMillan

Overview

This chapter explains why studying a biomechanical frame of reference within occupational therapy is relevant in today’s practice. The profession continues to have a contract with society to provide a service that focuses on human occupation. Occupational therapists are concerned with the relationship between people’s occupations and their health, and assess people’s disengagement from their occupations, provide ways for them to re-engage in their occupations, or suggest alternatives so that people’s quality of life may improve. Core values and beliefs about the importance of occupation to humans constitute a paradigm of occupation. In daily practice, occupational role issues that individuals may experience can be appreciated by referring to conceptual models of practice using a ‘top-down’ approach. Examples of such models of practice are the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP) (see Chapter 7 for further information) and the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (see Chapter 6 for further information). Such models provide the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to understand how we can analyse, intervene and evaluate individuals in relation to their roles and efficacy of occupational performances, e.g. in self-care, work and leisure. However, in order to understand the individual’s specific occupational performance problems, it is also necessary to analyse and understand their ‘performance capacities’ in more detail. Performance capacities refer to cognition, behaviour, neural development, personal interactions and, most importantly for this chapter, movement. The biomechanical frame of reference deals exclusively with the capacity for motion, whilst other frames of reference deal with other capacities, e.g. the cognitive behavioural frame of reference deals with cognition and behaviour. A biomechanical frame of reference may be useful in assessment, intervention and evaluation with people who have occupational performance problems, created primarily by some disease, injury or event that impinges on their voluntary movement, muscle strength, endurance or usually a combination of all three. The loss of one or more of these capacities will interfere to some degree with an individual’s ability to perform their occupations to their satisfaction. The biomechanical frame of reference assists in understanding the assessment, intervention and evaluation strategies associated with changing physical performance capacities in order to help individuals re-engage in their occupations.

• This chapter explores the evolution and use of a biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy.

• The biomechanical frame of reference can be located within a ‘top-down’ and a ‘bottom-up’ approach to occupational therapy.

• The biomechanical frame of reference deals with a person’s problems related to their capacity for movement in daily occupations.

• The biomechanical frame of reference can be used to shape assessment, intervention and evaluation strategies, in order to help individuals re-engage in their occupations.

Introduction

The ‘biomechanical frame of reference’, in its original form, was not necessarily compiled by occupational therapists for occupational therapy practice today and therefore some translation of the original frame of reference (from a professional perspective) is necessary in order to ensure a ‘fit’ with the philosophy of occupational therapy. Therefore, this chapter describes and articulates a biomechanical frame of reference from an occupational therapist’s perspective.

The biomechanical frame of reference used in occupational therapy has a long tradition and at different points in history has been termed Baldwin’s reconstruction approach 1919, Taylor’s orthopaedic approach 1934, and Licht’s kinetic approach 1957 (Turner et al 2002). This frame of reference continues to be widely used today and different occupational therapists are continuing to present this frame of reference in different ways (for example, Trombly appears to have incorporated a biomechanical frame of reference into the Occupational Functioning Model; Trombly & Radomski 2002).

Reflecting on this biomechanical frame of reference (which encompasses a variety of knowledge, skills and attitudes) broadens a professional’s knowledge base and provides more insight into fieldwork experiences and therefore an understanding of how practice can inform theory-building and vice versa.

Conceptual models of practice

Occupation (Kielhofner, 1997 and Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2002), within the context of occupational therapy, is part of the human condition, is necessary to society and culture, is required for physical and psychological well-being, entails underlying performance components and is a determinant and product of human development. Further, the intrinsic values of occupational therapy as a practice grounded in humanism affirm the dignity and worth of individuals, the participation in occupation, self-determination, freedom and independence, latent capacity, caring and the interpersonal elements of therapy, human uniqueness and subjectivity, and mutual cooperation in the therapeutic process. Occupation and occupational performance are usually expressed in terms of self-care/daily living tasks, work/productivity and leisure/play (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists, 2002 and Kielhofner, 2007).

This infers that studying and considering human occupation has to be paramount and is the core business of being an occupational therapist. When necessary, occupation can be analysed (e.g. the biological, psychosocial, environmental, etc.) regarding its content and meaning for the individual, to determine ‘dysfunctional elements’ that may occur because of disease and injury. Occupational therapists who can expertly analyse occupations are then able to perceive the meaning for that person and to assist them in regaining the necessary skills (or compensate for their permanent loss) through the medium of occupation and/or by modifying the environment or the attitudes of others in society and so on.

If an individual has temporarily or permanently lost an occupational role because of occupational performance problems primarily concerning movement, then the biomechanical frame of reference is likely to inform the therapist and assist the overall therapeutic process.

Ultimately, the majority of clients seen by an occupational therapist will have problems of ‘body and mind’ (irrespective of diagnostic labels), which can only be discerned within the context of that individual’s environment, perspectives and value systems. This requires adopting a top-down approach to practice (Kramer et al 2003) by using an occupational therapy conceptual model of practice to appreciate the significance of an individual’s occupational performance problems and then using the biomechanical frame of reference and others to appreciate the performance capacity issues.

Top-down approach to practice

The values and beliefs inherent in an occupation paradigm imply that occupational therapists need to view their clients as occupational beings. We therefore need to choose conceptual models of practice that focus on describing the occupational nature of the client. There are a number of unique occupational therapy models of practice available to choose from, such as the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner 2007), the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP) (Law et al 2005) and the Person–Environment–Occupation Model (Law et al., 1996 and Strong et al., 1999). Practice can then be further supported with other frames of reference when required (e.g. the biomechanical frame of reference), so that occupational performance issues relative to motion in occupations can be more specifically analysed and managed.

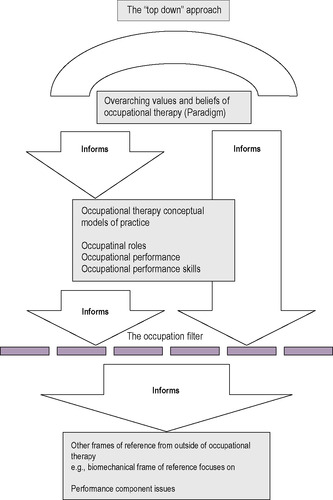

Figure 14.1 implies that the occupation paradigm influences every aspect of an occupational therapist’s practice. The use of knowledge located in a biomechanical frame of reference needs to be filtered (occupation filter) by values that an occupational therapist embodies, which are located within the occupation paradigm. This ensures that the focus of interventions remains occupational in nature. The focus of the biomechanical frame of reference is the musculoskeletal capacity to create movement (range of motion), strength and endurance in order to carry out meaningful occupations. Movement, strength and endurance can then be assessed within the context of a person completing their occupations and using occupations to restore/maintain/compensate for lack of movement, strength and endurance.

|

| Fig. 14.1 • The ‘top-down’ approach. Reproduced with permission from Forsyth and McMillan, personal communication, (2001). |

Occupation filter

The following criteria constitute the occupation filter and occupational therapists ought to reflect on these statements when using the technology of the biomechanical frame of reference to enrich practice (Mallinson & Forsyth, personal communication 2000):

• Person’s occupational performance. The primary concern here is understanding how the phenomena from the biomechanical frame of reference (movement, strength and endurance) influence the person’s performance of their occupational roles.

• Assess through occupation. Analyse and assess the phenomena from the biomechanical frame of reference (movement, strength and endurance) within the context of the person’s performance of their occupational roles.

• Occupation restores/maintains. This reinforces the person’s performance of occupational roles during the restoration and/or maintenance and/or compensation of movement, strength and endurance.

• The outcome of occupational therapy is satisfying/meaningful performance in occupations. Occupational therapists ought to view the satisfying, meaningful performance of occupation as the primary outcome of therapy (Mallinson & Forsyth, personal communication 2000).

Using the top-down approach above implies that a biomechanical frame of reference used by an occupational therapist will be different from a biomechanical frame of reference used by other health professionals.

Occupation and occupational performance that incorporate movement and its potential restoration are the key to understanding the use of this frame of reference in our professional practice. Movement for the sake of movement is more likely to be the aim of other professionals, reflecting a bottom-up approach (Kramer et al 2003).

Details of the biomechanical frame of reference

The biomechanical frame of reference in occupational therapy is primarily concerned with an individual’s motion during occupations. Motion in this context can be understood in more detail as the capacity for movement, muscle strength and endurance (the ability to resist fatigue).

An individual’s quality of motion may be compromised as they carry out their occupations due to the effects of disease or injury. These effects may compromise specific body systems and structures (e.g. bones and joints) that help create motion seen during occupational performance. Additionally, an individual’s quality of movement has to be viewed in the context of the environment that may facilitate or inhibit their occupations.

Aim and objectives

The biomechanical frame of reference aims to address the quality of movement in occupations. Specific objectives are to:

• prevent deterioration and maintain existing movement for occupational performance

• restore movement for occupational performance, if possible

• compensate/adapt for loss of movement in occupational performance.

Compensation and adaptation are terms that have often been associated with ‘rehabilitation’ or the ‘rehabilitative model’. Some practitioners believe the biomechanical frame of reference deals comprehensively with the topic of compensation and some believe that a rehabilitation model deals with compensation. This author believes that rehabilitation may be viewed as an ‘aim’ and that compensation is more comprehensively addressed within the biomechanical frame of reference.

Who would you use the biomechanical frame of reference with?

This frame of reference is principally used with individuals who experience the following problems in their daily occupations.

Limitations in movement during occupations

This describes the capacity of the person to use their muscles in conjunction with bones and joints to move freely when engaging in occupations. This is usually due to one or more of the following problems:

• shortening (contracture) of soft tissues, i.e. muscle tissue, muscle connective tissues, tendons, ligaments, fibrous capsules and skin

• the presence of inflammation, oedema or haematoma

• localized destruction of bone (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthrosis)

• amputation

• congenital abnormalities

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental conditions.

Inadequate muscle strength for use in occupations

This describes the capacity of the person to initiate and maintain muscle strength during their occupations (e.g. using the forearm muscle groups to facilitate gripping an object effectively in the hand). Inability to do this may be due to one or more of the following problems:

• limitations in movement

• disuse or atrophy of muscle (e.g. post-fracture immobilization)

• primary muscle pathology (e.g. muscular dystrophy)

• anterior horn cell pathology (e.g. motor neurone disease)

• peripheral neuropathy (e.g. diabetes)

• peripheral nerve damage (e.g. mononeuropathy of the median nerve)

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental conditions.

Loss of endurance in occupations

This describes the ability of the person to resist subjective fatigue and therefore sustain their occupations over time and distance to their satisfaction. Issues in this area are usually due to one or more of the following problems:

• limitations in movement

• inadequate muscle strength

• compromised cardiovascular and/or respiratory function

• acute and chronic pain

• maladaptive environmental factors.

Biomedical conditions

People who experience limitations in movement, inadequate muscle strength and loss of endurance whilst engaging in their occupations may have a diagnosis of one or more of the following biomedical conditions:

• rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthrosis or a combination of the two, or the individual may have experienced surgical arthroplasty

• amputations, burns and other soft-tissue damage frequently seen in hand and limb injuries

• fractures and various orthopaedic conditions

• Guillain–Barré syndrome, muscular dystrophy, motor neurone disease and the long-term effects of poliomyelitis (post-polio syndrome)

• peripheral neuropathy, mononeuropathy, brachial plexus lesions

• cardiac problems in the form of ischaemic heart disease (angina, myocardial infarction), cardiac failure or the effects of bypass surgery

• respiratory problems in the form of various obstructive airways diseases

• chronic pain due to occupational overuse syndrome (OOS), back injuries, neck injuries or pain associated with any of the conditions outlined above.

To appreciate the application of the biomechanical frame of reference fully implies an understanding not only of the biomedical conditions outlined above but also of the anatomical and physiological details of certain body systems and structures, which are outlined below:

• the musculoskeletal system, which comprises muscles, tendons, ligaments, bone and related tissues, and synovial joints (fibrous capsules, synovial tissues)

• the peripheral nervous system, comprising neural and connective tissues

• the integumentary system, comprising the epidermis, dermis, blood vessels, hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands

• the cardiorespiratory system, comprising the heart, blood vessels and lungs.

It should also be understood that, because the biomechanical frame of reference principally concerns the capacity to execute purposeful movement in everyday occupations, it is important to understand other factors that underpin this concept.

Other factors

It is helpful to have an understanding of the following factors. Understanding the biomechanical basis of movement includes knowing the locomotor system (how bones and joints perform together, especially in relation to the appendicular skeleton), active and passive joint range of movement (a.ROM and p.ROM), the function of skeletal muscle, types of muscle work (concentric and eccentric, isotonic and isometric contraction), muscle architecture and role, the peripheral nervous system (motor, sensory and autonomic) and the relationship between the peripheral nervous system (synaptic transmission and innervation) and muscles (sliding filament theory).

In addition, the biomechanical basis of movement includes understanding concepts of force, gravity, friction, resistance, leverage, stability and equilibrium, and how these elements interact to affect the nature of motion in human beings (Spaulding 2005).

The relationship between occupational performance and the biomechanical frame of reference requires understanding locomotion and the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle, prehension and the prehensile patterns of hand grips (power and precision), skeletal muscle and cardiovascular endurance, and the effects of fatigue on human occupations, all of which have to be considered for the execution of purposeful motion. Tyldesley and Grieve (2002) provide a detailed explanation of all of the above and this text is recommended as further reading to understand these factors in greater detail.

In summary, the capacity for movement (and occupational performance) is a synthesis of forces (the capabilities of the musculoskeletal system and the nervous system coordinating the work of groups of muscles to produce movement and stabilize joints) acting on the body. Endurance (the ability to sustain occupational performance) is predominantly a function of muscle physiology and the ability of the body systems to transport the required material towards, and waste materials away from, the muscle tissues.

Individuals’ problems that can be addressed through the biomechanical frame of reference should have an intact, fully matured central nervous system. In other words, no evidence of biomedical conditions or pathology that might affect the following body systems should be evident:

• motor control systems (cortex/basal ganglia/cerebellum)

• sensory discrimination (cortex/thalamus/cerebellum)

• perceptual qualities (association areas of the cortex and parietal lobe functions)

• cognition (localization of function)

• behaviour (localization of function).

This is because the individual with movement problems described in the biomechanical frame of reference still has the capacity in their central nervous system to initiate the production of smooth, controlled isolated movements (Dutton 1998). This is in sharp contrast to individuals with central nervous system (CNS) damage who would have different types of motor problem and therefore a different frame of reference would have to be considered, i.e. the theoretical approaches to motor control and cognitive function (see Chapter 15 for further information). However, it is also apparent that occupational therapists do use the technology of the biomechanical frame of reference at certain times with selected individuals who do have CNS damage in the form of stroke, multiple sclerosis and so on. This is because, inevitably, some individuals do sustain permanent loss of the control of movement in various parts of their body, and in the long term compensating for this loss of motion in occupational performance is required.

The next part of this chapter concentrates on the assessment of movement seen in occupational performance.

Principles of assessment and measurement

Rationale for assessment

Occupational therapists ought to be concerned with the principles of assessment and measurement in their practice to facilitate collaborative goals, build intervention plans and document measures of outcomes. This process of assessment can be undertaken through client-driven assessment, therapist observation and the use of standardized and non-standardized instruments.

Assessment facilitates the collection of quantitative and qualitative data, which, when analysed, permit the interpretation of the effectiveness of an intervention by both the client and the therapist. This interpretative process, in relation to hard and soft data, assists in monitoring and implementing change, helps in building goals, facilitates decision-making and produces evidence that is readily understood, for the benefit of clients and of health professional and managerial colleagues.

General aims of assessment

The aims of occupational therapy assessment are generally agreed to:

• decide whether occupational therapy is appropriate or necessary

• establish abilities, disabilities and the effects of the environment on an individual’s occupations

• formulate a package of information (data collection) to plan future goals

• formulate a baseline to compare progress and regress

• assist decision-making regarding the modification of intervention plans

• involve, inform, educate and motivate the individual (client)

• establish the efficacy (and evidence base) of occupational therapy intervention

• assist resource decision-making regarding demands on service provision

• produce tangible outcomes/evidence for the benefit of the individual and of healthcare and management colleagues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree