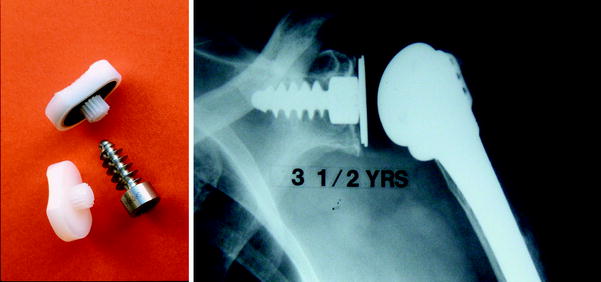

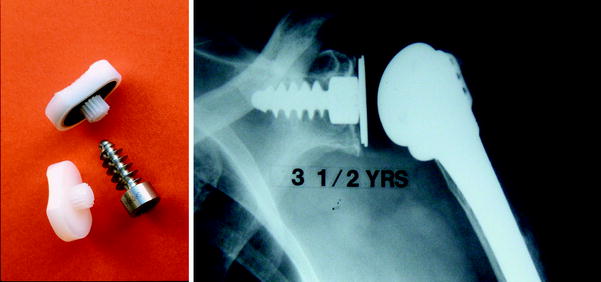

Fig. 43.1

Kessel’s fixed fulcrum reverse polarity shoulder prosthesis

As noted, these devices were designed for end stage rheumatoid arthritis in which pain relief and stability for load bearing were paramount. History records that those (the majority) using cement on the glenoid side loosened after a relatively short time [1]. Consequently, the fixed fulcrum concept fell into disrepute with the mantra that “all fixed fulcrum replacements will loosen”.

In common with other fixed fulcrum implants, the Kessel device delivered good pain relief and modest improvements of function in the short term [2, 3]. However, in contrast to other devices, it also appeared to do so into the medium term with a late loosening rate of 13 % in a cohort of an initial 33 shoulders followed-up for between 8 and 16 years [4] which compared favorably in the UK practice of the time with the sort of survival rates being reported for early use of cemented unconstrained devices, in concentric osteoarthritis, and with subsequent concerns of progressive radio lucent lines in such devices [5].

Thus, the lesson of the Kessel prosthesis was that even a “bad” design with a stainless steel screw and fixed fulcrum configuration could achieve durability in low demand patients with uncemented glenoid fixation. Accordingly, using this learning, in our center we extrapolated the concept into an unconstrained modular device for use in concentric osteoarthritis. Based on the Kessel screw, the glenoid prosthesis was made of smooth titanium to encourage osseointegration (Fig. 43.2). From 1989, this became the standard device used in our unit, delivering an effective response for shoulders with “good cuff and good glenoid bone” together with “good cuff and poor glenoid bone” situations.

Fig. 43.2

AMBS unconstrained shoulder replacement

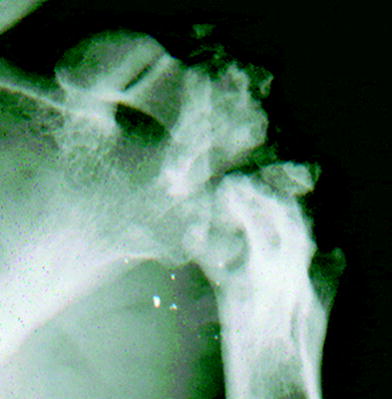

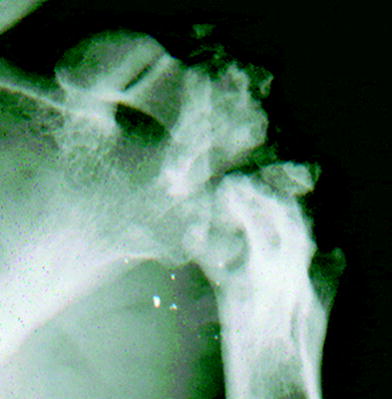

Within a very few years however two factors altered our thinking about fixed fulcrum design. First was the type of case we were being asked to treat in which, usually as a result of trauma, conventional anatomical devices were inadequate (Fig. 43.3). Second, it was becoming clearer that hemiarthroplasty was not the answer in cuff arthropathy: in other words, the solution in “no cuff and good glenoid bone” cases required re-evaluation. As a result of these twin factors, we revived our interest in the fixed fulcrum concept.

Fig. 43.3

Unsuitable for anatomical shoulder replacement

Learning from our experiences with the Kessel replacement, and focussing on the important issue of durability, it was clear that we needed to improve on the efficiency of osseointegration of the glenoid screw. Kessel’s device had generated lucent line rates of 80 % with only 20 % osseointegration rates. While most of the lucent lines were less than 2 mm in thickness and apparently stable and allowing continued satisfactory function, it was clear that for a new prosthesis to be suitable for durable use in higher demand patients, the glenoid osseointegration rates needed to be dramatically improved.

Retaining the principles of a central uncemented screw that sought to take fixation from the cortical bone, the new prosthesis also sought to take advantage of the modern development of hydroxyapatite-coated titanium. In addition, the new prosthesis sought to fit the glenoid with a conical shape. The hybrid nature of Kessel’s device was retained but the cemented plastic peg was replaced by a cemented metal pipestem with a plastic liner within the bowl. The snap fit nature of the Kessel “ball in socket” device was retained to guard against dislocation in the cuffless shoulder even in the absence of subscapularis. The first of these implants was inserted in 1994 and the device remains in use, essentially unchanged, to the present time. Subsequent finite element studies have confirmed the superiority of a device which gains fixation in the cortical bone of the glenoid [6]. A 20 % osseointegration for the Kessel has been converted to 80 % in the current device, and durability has been correspondingly improved with an aseptic loosening revision rate of 6 of 103 prostheses inserted between 1995 and 2008 with a minimum follow-up of 12 months [7]. Further, our experience has shown that if the glenoid screw remains secure at 2 years [8], it will usually remain so at least over the 20 years the prosthesis has been in use. Clinical outcome measures in a study of 89 shoulders with an average follow-up of 50 months (24–96) [8] demonstrate on average an 85 % gain in active forward elevation (42º–78º) and a 260 % gain in active external rotation (9º–24º). Active internal rotation can be improved on average by one level on a six-level scale ascending from the side of the hip up behind the back to level with the scapula (2.3 improving to 3.2 levels). The Oxford Score measured by the original method can be improved on average from 47 to 28 points and a percentage of normal score [9, 10] can be improved on average from 24 % of normal to 61 % [8].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree