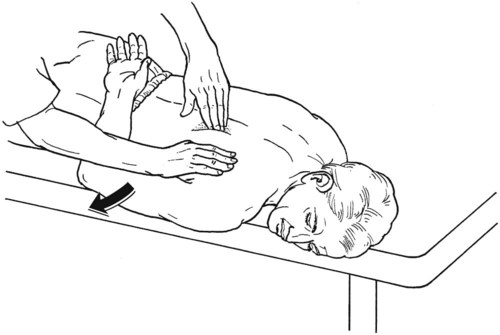

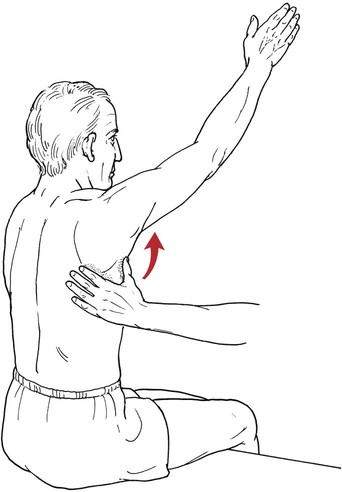

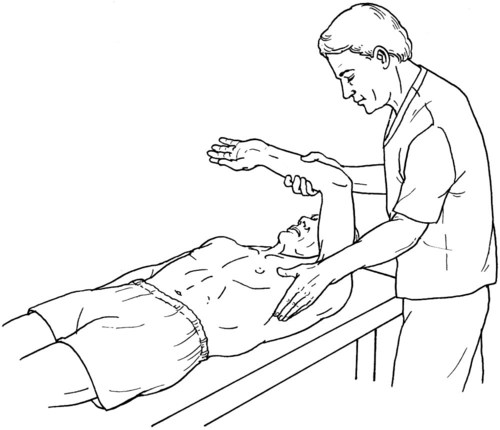

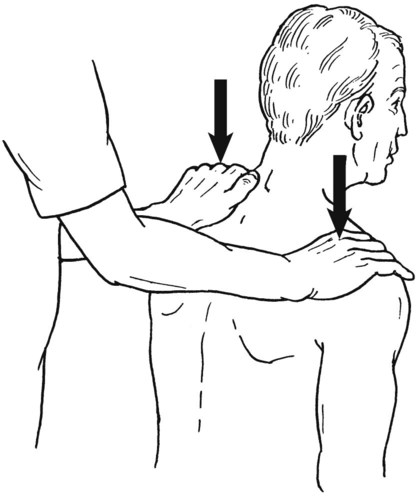

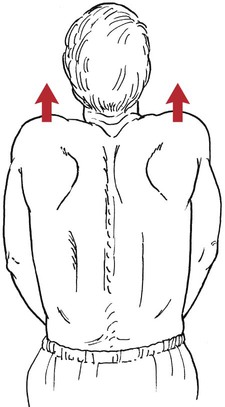

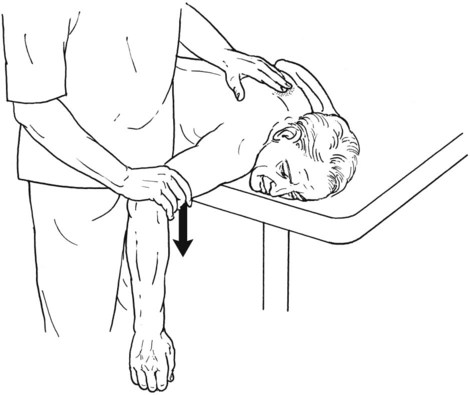

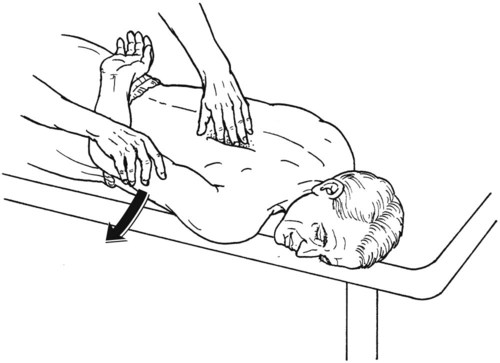

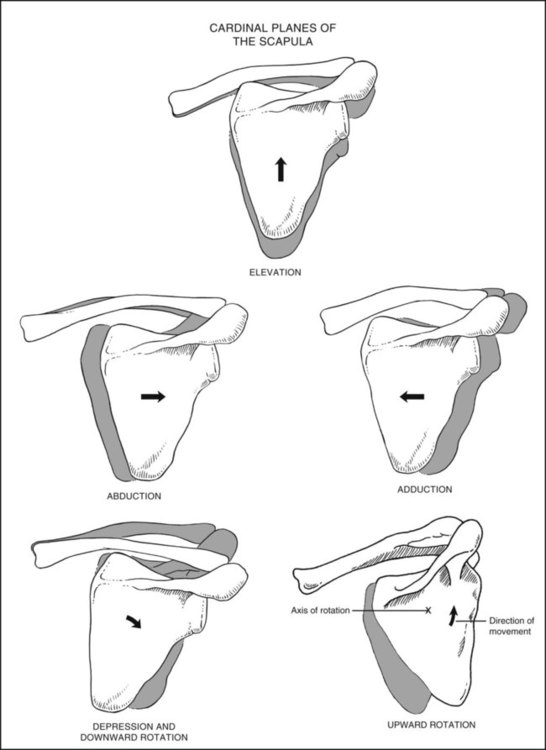

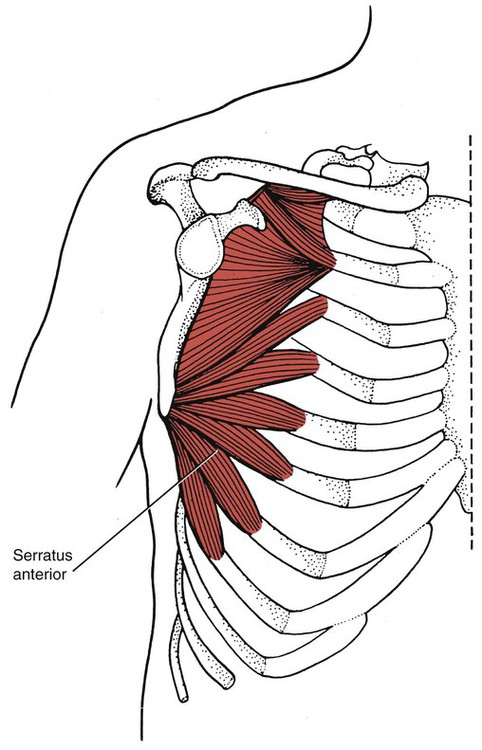

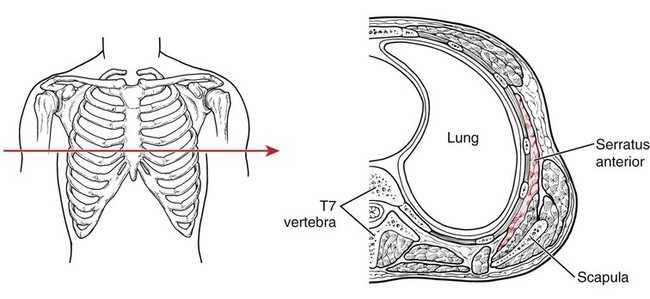

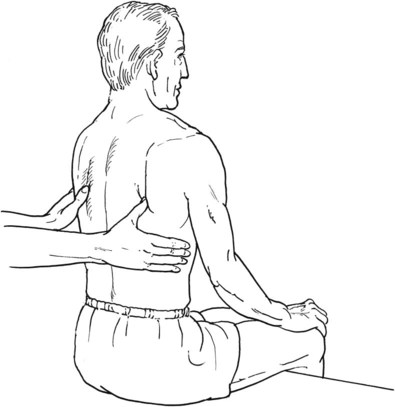

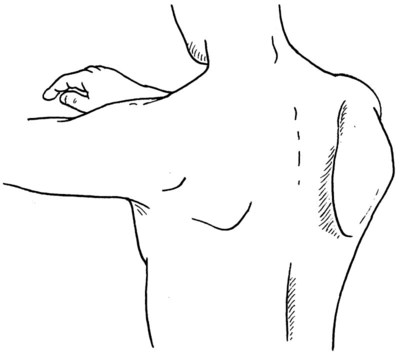

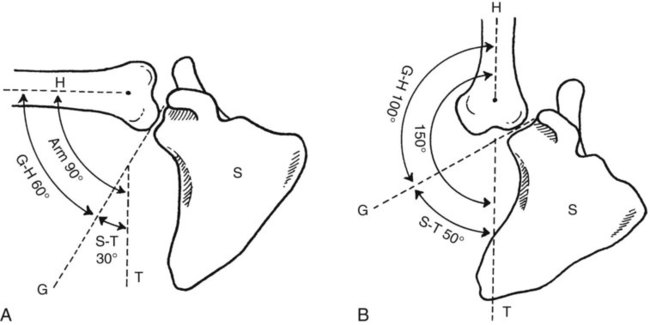

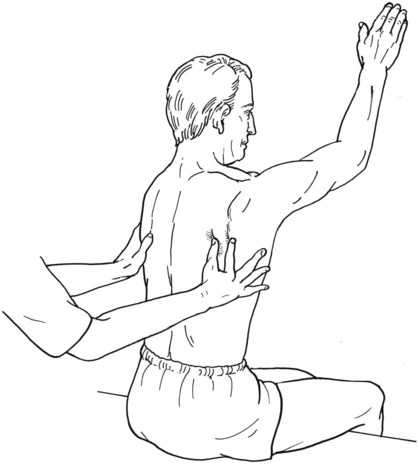

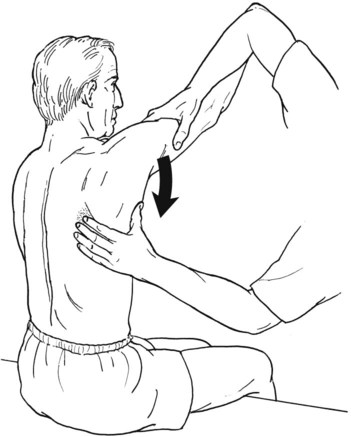

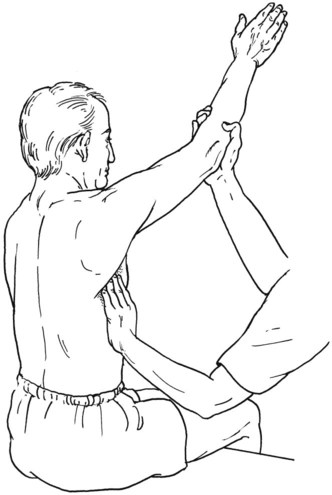

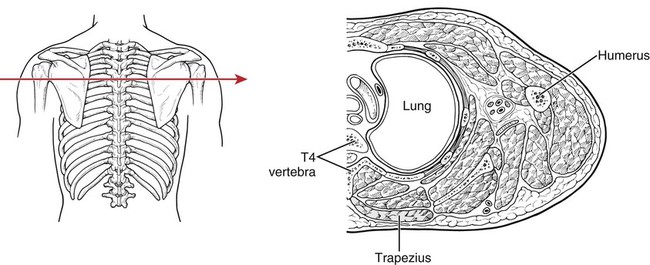

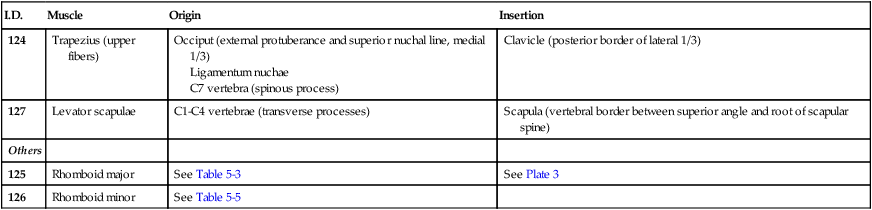

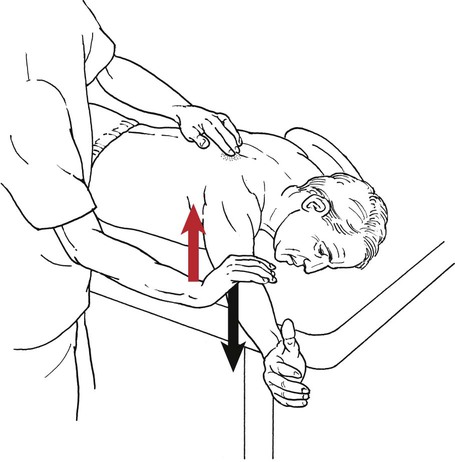

Table 5-1 SCAPULAR ABDUCTION AND UPWARD ROTATION Palpate the vertebral borders of both scapulae with the thumbs; place the web of the thumb below the inferior angle; the fingers extend around the axillary borders (Figure 5-4). The normal scapula lies close to the rib cage with the vertebral border nearly parallel to and from 1 to 3 inches lateral to the spinous processes. The inferior angle is on the chest wall. The most prominent abnormal posture of the scapula is “winging,” in which the vertebral border tilts away from the rib cage, a sign indicative of serratus anterior weakness (Figure 5-5). Other abnormal postures are abduction and downward rotation of the scapula. If the inferior angle of the scapula is tilted away from the rib cage, check for tightness of the pectoralis minor, weakness of the trapezius, and spinal deformity. a. The scapula sits against the thorax (T) during the first phase of shoulder abduction and flexion to provide initial stability as the humerus (H) abducts and flexes to 30°. b. From 30° to 90° of flexion and abduction, the glenohumeral (G-H) joint contributes another 30° of motion, whereas the scapula upwardly rotates 30°. The upward rotation is accompanied by clavicular elevation through the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints (Figure 5-6, A). c. The second phase (90° to 180°) is made up of 60° of glenohumeral abduction and flexion and an additional 30° of scapular upward rotation. The scapular rotation is associated with 5° of elevation at the sternoclavicular joint and 25° of rotation at the acromioclavicular joint (Figure 5-6, B). Passively raise the test arm completely above the head in forward flexion to determine scapular mobility. The scapula should start to rotate at about 30°, although there is considerable individual variation. Scapular rotation continues until about −20° to −30° from full flexion. The serratus should always be tested in shoulder flexion to minimize the synergy with the trapezius. If the scapular position at rest is normal, ask the patient to raise the test arm above the head in the sagittal plane. If the arm can be raised well above 90° (glenohumeral muscles must be at least Grade 3 to do this), observe the direction and amount of scapular motion that occur. Normally, the scapula rotates forward in a motion that is controlled by the serratus, and if erratic or “uncoordinated” motion occurs, the serratus is most likely weak. The normal amount of motion of the vertebral border from the start position is about the breadth of two fingers (Figure 5-7). If the patient is able to raise the arm with simultaneous rhythmical scapular upward rotation, proceed with the test sequence for Grades 5 and 4. Standing at test side of patient. Hand giving resistance is on the arm proximal to the elbow (Figure 5-8). The other hand uses the web space along with the thumb and index finger to palpate the edges of the scapula at the inferior angle and along the vertebral and axillary borders. Standing at test side of patient. One hand supports the patient’s arm at the elbow, maintaining it above the horizontal (Figure 5-10). The other hand is placed at the inferior angle of the scapula with the thumb positioned along the axillary border and the fingers along the vertebral border (see Figure 5-10). Standing in front of and slightly to one side of patient. Support the patient’s arm at the elbow, maintaining it above 90° (Figure 5-11). Use the other hand to palpate the serratus with the tips of the fingers just in front of the inferior angle along the axillary border (see Figure 5-11). Table 5-2 It is important to examine the patient’s shoulders and scapula from a posterior view and to note any asymmetry of shoulder height, muscular bulk, or scapular winging. This kind of asymmetry is common and can be caused by carrying purses or briefcases habitually on one side (Figure 5-16). Table 5-3 SCAPULAR ADDUCTION (RETRACTION) 1. When the posterior deltoid is Grade 3 or better: The hand for resistance is placed over the distal end of the humerus, and resistance is directed downward toward the floor (see Figure 5-23). The wrist also may be used for a longer lever, but the lever selected should be maintained consistently throughout the test. 2. When the posterior deltoid is Grade 2 or less: Resistance is given in a downward direction (toward floor) with the hand contoured over the shoulder joint (Figure 5-24). This placement of resistance requires less adductor muscle strength by the patient than is needed in the test described in the preceding paragraph. The fingers of the other hand can palpate the middle fibers of the trapezius at the spine of the scapula from the acromion to the vertebral column if necessary (Figure 5-25). Table 5-4 SCAPULAR DEPRESSION AND ADDUCTION Standing at test side. Hand giving resistance is contoured over the distal humerus just proximal to the elbow (Figure 5-30). Resistance will be given straight downward (toward the floor). For a less rigorous test, resistance may be given over the axillary border of the scapula. Table 5-5 SCAPULAR ADDUCTION AND DOWNWARD ROTATION The test for the rhomboid muscles has become the focus of some clinical debate. Kendall and co-workers claim, with good evidence, that these muscles frequently are underrated; that is, they are too often graded at a level less than their performance.1 At issue also is the confusion that can occur in separating the function of the rhomboids from those of other scapular or shoulder muscles, particularly the trapezius and the pectoralis minor. Because the rhomboids are innervated only by C5, a test for the rhomboids, correctly conducted, can confirm or rule out a nerve root lesion at this level. With these issues in mind, the authors present first their method and then, with the generous permission of Mrs. Kendall, her rhomboid test as another method of assessment. Standing at test side. When the shoulder extensor muscles are Grade 3 or higher, the hand used for resistance is placed on the humerus just above the elbow, and resistance is given in a downward and outward direction (Figure 5-37). When the shoulder extensors are weak, place the hand for resistance along the axillary border of the scapula (Figure 5-38). Resistance is applied in a downward and outward direction.

Testing the Muscles of the Upper Extremity

Scapular Abduction and Upward Rotation

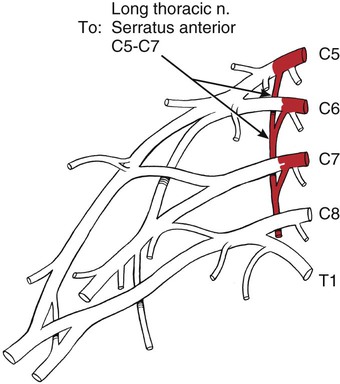

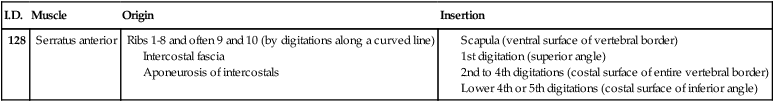

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

128

Serratus anterior

Ribs 1-8 and often 9 and 10 (by digitations along a curved line)

Intercostal fascia

Aponeurosis of intercostals

Introduction to Scapular-Thoracic Muscle Testing

Preliminary Examination

Specific Elements

Position and symmetry of scapulae:

Scapular range of motion:

Grade 5 (Normal) and Grade 4 (Good)

Position of Therapist:

Grade 2 (Poor)

Position of Therapist:

Grade 1 (Trace) and Grade 0 (Zero)

Position of Therapist:

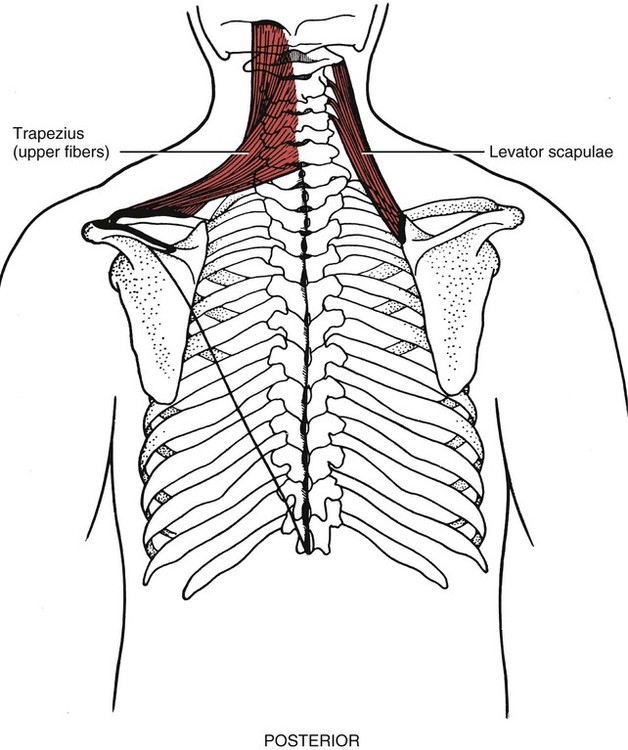

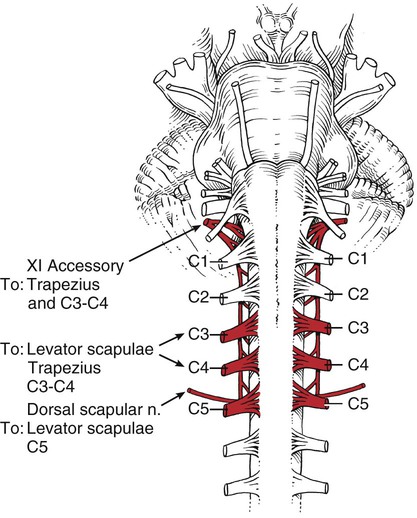

Scapular Elevation

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

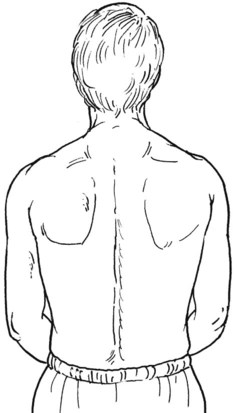

124

Trapezius (upper fibers)

Occiput (external protuberance and superior nuchal line, medial 1/3)

Ligamentum nuchae

C7 vertebra (spinous process)

Clavicle (posterior border of lateral 1/3)

127

Levator scapulae

C1-C4 vertebrae (transverse processes)

Scapula (vertebral border between superior angle and root of scapular spine)

Others

125

Rhomboid major

See Table 5-3

See Plate 3

126

Rhomboid minor

See Table 5-5

Grade 5 (Normal) and Grade 4 (Good)

Test:

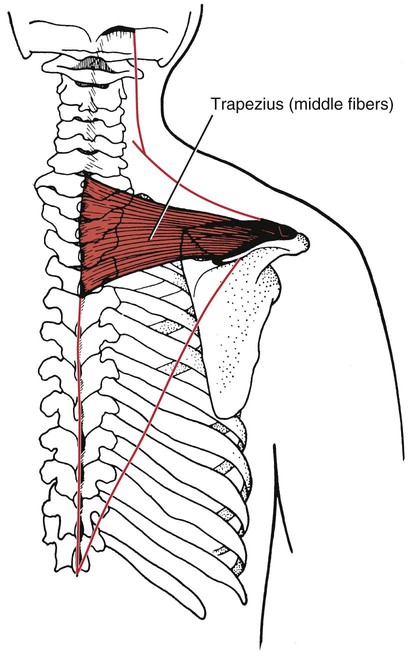

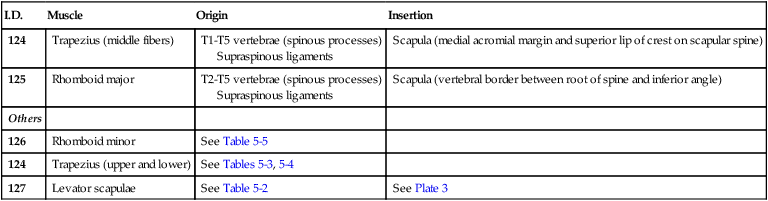

Scapular Adduction

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

124

Trapezius (middle fibers)

T1-T5 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Supraspinous ligaments

Scapula (medial acromial margin and superior lip of crest on scapular spine)

125

Rhomboid major

T2-T5 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Supraspinous ligaments

Scapula (vertebral border between root of spine and inferior angle)

Others

126

Rhomboid minor

See Table 5-5

124

Trapezius (upper and lower)

See Tables 5-3, 5-4

127

Levator scapulae

See Table 5-2

See Plate 3

Grade 5 (Normal), Grade 4 (Good), and Grade 3 (Fair)

Position of Therapist:

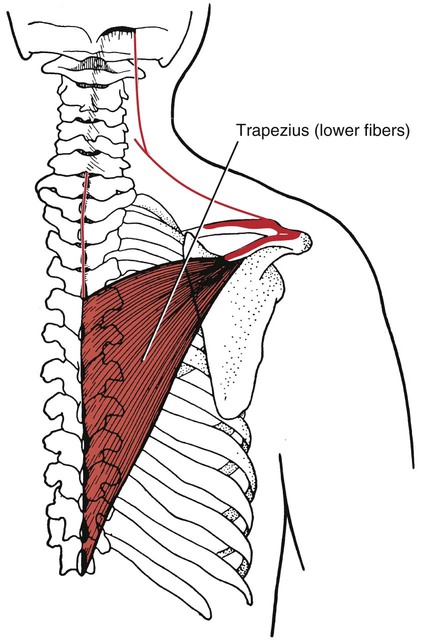

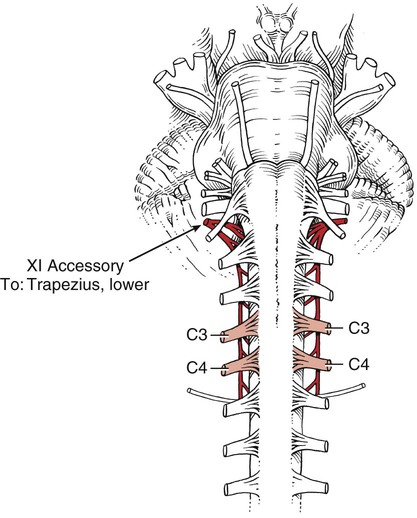

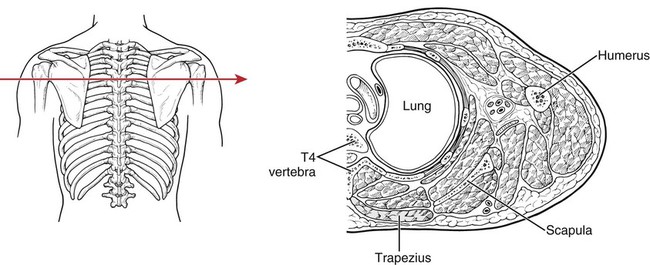

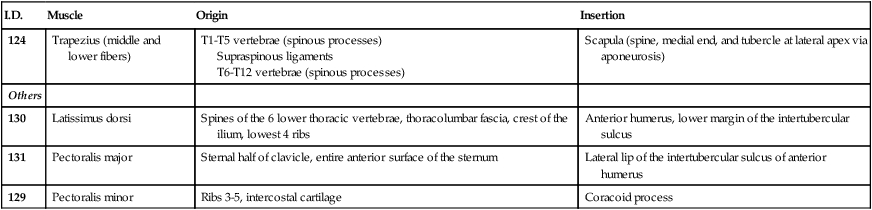

Scapular Depression and Adduction

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

124

Trapezius (middle and lower fibers)

T1-T5 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Supraspinous ligaments

T6-T12 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Scapula (spine, medial end, and tubercle at lateral apex via aponeurosis)

Others

130

Latissimus dorsi

Spines of the 6 lower thoracic vertebrae, thoracolumbar fascia, crest of the ilium, lowest 4 ribs

Anterior humerus, lower margin of the intertubercular sulcus

131

Pectoralis major

Sternal half of clavicle, entire anterior surface of the sternum

Lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus of anterior humerus

129

Pectoralis minor

Ribs 3-5, intercostal cartilage

Coracoid process

Grade 5 (Normal) Grade 4 (Good), and Grade 3 (Fair)

Position of Therapist:

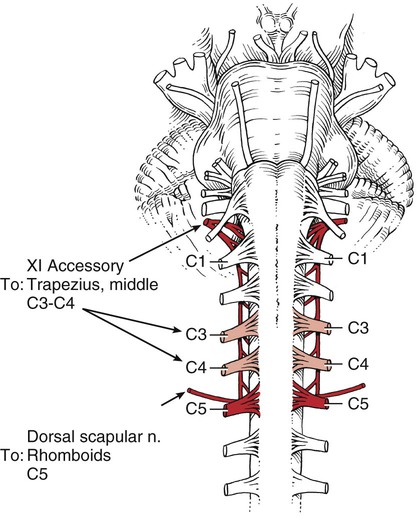

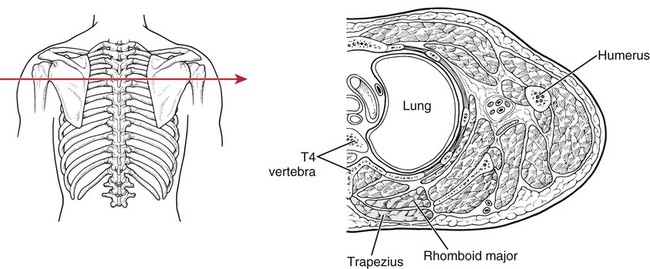

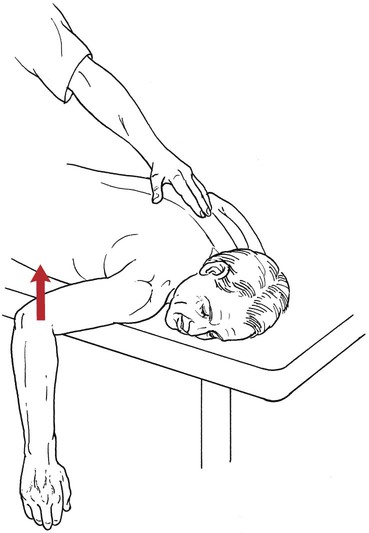

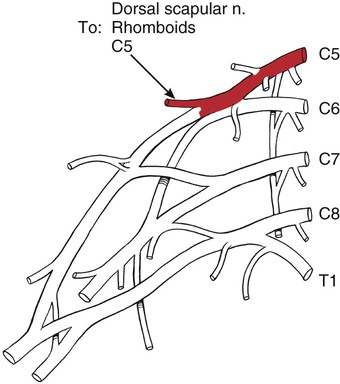

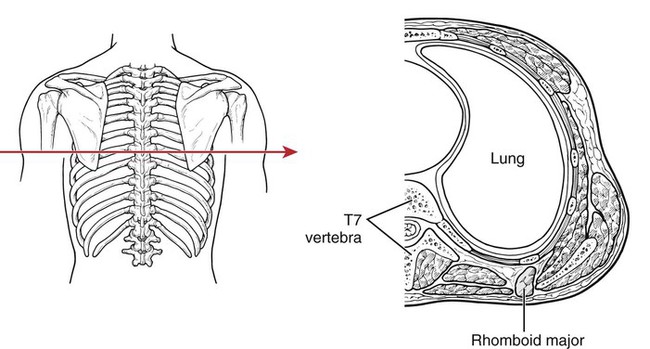

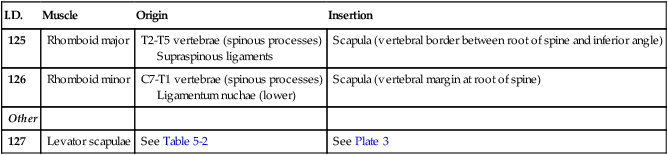

Scapular Adduction and Downward Rotation

I.D.

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

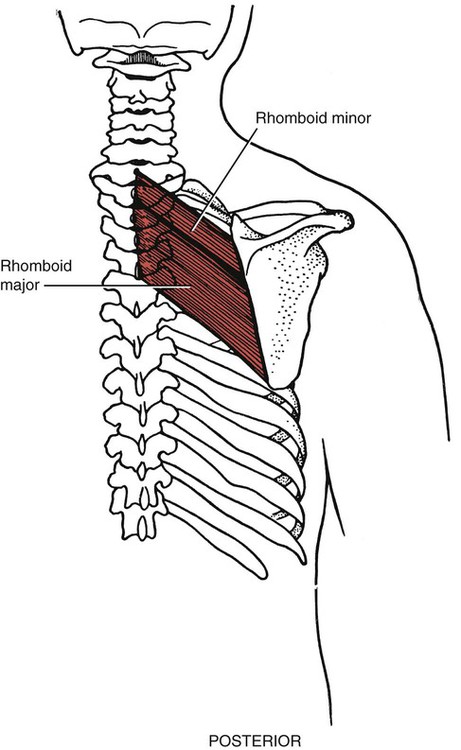

125

Rhomboid major

T2-T5 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Supraspinous ligaments

Scapula (vertebral border between root of spine and inferior angle)

126

Rhomboid minor

C7-T1 vertebrae (spinous processes)

Ligamentum nuchae (lower)

Scapula (vertebral margin at root of spine)

Other

127

Levator scapulae

See Table 5-2

See Plate 3

Grade 5 (Normal), Grade 4 (Good), and Grade 3 (Fair)

Position of Therapist: