Chapter 9 Techniques for Teaching Students in Clinical Settings

Clinical education has long been recognized as a necessary part of physical therapy education. In 1968, Callahan and colleagues stated that the purpose of clinical education was “to assist the student to correlate clinical practices with basic sciences; to acquire new knowledge, attitudes and skill to develop ability to observe, to evaluate, to develop realistic goals and plan effective treatment programs; to accept professional responsibility; to maintain a spirit of inquiry and to develop a pattern for continuing education.”1 Despite major changes in health care delivery and physical therapy, this purpose reflects the present goal of physical therapy clinical education.

CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR: Jeff is a bright student. He’s enthusiastic and eager to learn. I know this is only his second clinical affiliation and he hasn’t had all of his classroom work yet, but he’s on the right track. I’ve really tried to spend time teaching him. I wanted that when I was a student. My CI just let me go for it on my own. I mean, I learned, but I would have liked to have had someone there giving me feedback and teaching me more advanced skills. I think this approach has helped Jeff.

JEFF: This is different from my first affiliation. I’m really just watching my CI most of the time. Like with the new patient I saw this morning. I started the history, but she interrupted and just kept asking all the questions. Then, I started the examination, but I guess I wasn’t doing something quite right, so she stepped in. It seems like she lectures to me all the time. I know I can’t do everything perfectly, but I’d just like to try. I could think of most of the things she did with the patient, but all I got to do was watch her. That’s not really true. She let me do the ultrasound.

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe the dynamic environment in which clinical education occurs.

2. Describe the clinical learning process and identify expected outcomes.

3. Discuss and give examples of the four roles of a clinical teacher.

4. Identify practical strategies for enhancing clinical teaching methods.

5. Promote the professional formation of students to facilitate the transition from clinical education to new graduate.

Context of clinical education

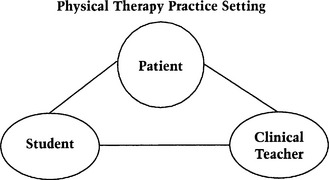

Clinical learning is situated in the context of physical therapy practice. It occurs in real practice settings, with real patients, and with real physical therapists as clinical teachers. Figure 9-1 diagrams the essential elements in clinical education that provide context for the learning experience.

Explicitly defining the desired outcome for each clinical experience dictates the appropriate timing in the curriculum, the duration of the experience, the type of setting, and the qualifications of the clinical teachers. Students’ early experiences may be even more critical than experiences that occur after the completion of the didactic curriculum because they are generally short, and the impact of the experience provides the framework for the student to develop patterns of lifelong clinical learning (Figure 9-2). The days of hands-off observation for students are over, although this may be the temptation in a busy clinical practice where productivity standards are high, and there is little time for teaching and practicing basic skills. Students must be ready to enter the clinic setting and interact with patients. They must know where to start. They must come with the expectation that they learn by thinking and doing with a patient.

Figure 9-2 Patient, student, and clinical instructor co-participate in an early clinical learning experience.

What does a student need to know on day 1 of a clinical learning experience? What is best taught in the classroom or the laboratory? What is best learned during a clinical education experience? Basic knowledge and skills are prerequisites to clinical learning. Consider the example given in Table 9–1. Muscle performance examinations are routinely provided by physical therapists. Knowledge of these examinations, as well as rudimentary skill in performing them, is acquired in the classroom and laboratory. In the clinical setting, the student learns to use this knowledge and skill in clinical decision making and patient management.

Table 9–1 Muscle Performance Examinations Provided by Physical Therapists

| Learning Environment | Primary Learning Activity |

|---|---|

| Classroom | Acquisition of knowledge |

| Laboratory | Acquisition of skill |

| Clinic | Use of knowledge and skill for clinical decision making and patient management in |

Adapted from American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, 2nd ed. Phys Ther 2001;81:9.

Prevailing conditions in the clinical environment

Scully2 suggests that there are three generic sources for the ground rules that frame the clinical learning environment: (1) those originating external to the clinical education facility, (2) those originating internal to the clinical education facility, and (3) those originating from within the clinical teacher. Table 9–2 gives examples of each. Although these delineations are helpful in understanding the origin of factors influencing the context of the clinical experience, examples may not fit exclusively in one category.

Table 9–2 Ground Rules Framing the Context of the Clinical Education Experience

| Sources | Examples |

|---|---|

| External | University mission and program objectives Assignment of students Time and length of assignment |

| Internal | Department policies and procedures Assignment of the clinical instructor Health requirements |

| Clinical teacher | Preparation and experience |

Adapted from Scully RM. Clinical Teaching of Physical Therapy Students in Clinical Education. Ph.D. dissertation. New York: Columbia University, 1974.

NATASHA: A pediatrics rotation is important to me. I don’t have much experience with children. But, I volunteered over the summer at a camp for kids with AIDS [acquired immunodeficiency syndrome], and I took the pediatric elective. It was tough, but I’m really excited about learning to do all we talked about. The student who was here last year said this was a great place!

ANNE: I’m not planning to get a job in pediatrics or anything. I just sort of got sent here—I was at the end of the lottery. I mean, I want to be well rounded and everything, but I don’t want to work with kids. I just want to get the basics. You know, so if kids ever come into my office I’ll know what to do with them.

CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR A: It’s going to be a long 8 weeks. Anne doesn’t want to be here. You can’t just learn the basics and expect to be a good physical therapist. Where do I even begin with her?

CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR B: I appreciate Anne’s honesty, and I hope I can work with her to become more diplomatic. I think there are many aspects of pediatric practice that apply to all patients. I think we can work together to create an excellent experience. I want to start by learning more about her interests.

ROBERTO: This hospital isn’t a very good place right now. There’s a lot of change going on. The patients are all seen in their rooms or in little satellite departments on the floors. It seems like all we do is get them out of bed. I don’t have time for a complete examination before they’re discharged. The biggest job the therapists have is deciding where to refer the patients when they’re discharged from the hospital. I want to do real physical therapy.

MARIAH: You’re absolutely right. I think we sometimes get the notion that physical therapy means using our hands all the time. Sometimes, though, the emphasis is on using our heads to think and plan. We can learn about the patient’s functional status before admission, we know what’s happened here, and then it’s our job to make the best possible guess about the future and make recommendations based on that. What a challenge! Discharge planning is a focus from the beginning, and even our treatments need to take that into consideration. What do you think about Mr. Baird, whom we saw this morning?

Prevailing conditions in the clinical environment provide additional opportunities and challenges for both the clinical teacher and the learner. The political climate of a given health care facility, reimbursement, interprofessional roles, productivity demands, and patient demographics represent just a few.3 Given these prevailing conditions, it is important to ask the following: How do students learn in the clinic? What is helpful for clinical teachers to know and understand about the clinical learning process?

Clinical learning

The purpose of this section is neither to review the work of learning theorists4–9 nor to examine the literature related to student physical therapists’ learning.10–15 Rather, this section provides a contextual basis of clinical learning to use in the upcoming section, Roles of the Clinical Teacher: Diagnosing Readiness, Planning, Teaching, and Evaluating. John Dewey provided key descriptors of the clinical learning process when he stated, “education is not an affair of ‘telling’ and being told, but an active and constructive process.”16 Successful clinical learning requires the student to make meaning of knowledge in a clinical sense and then to enact that meaning when providing physical therapy services.

Clinical learning occurs in the context of the “whole” as opposed to isolated parts of physical therapy care. As students learn to practice and practice learning, they acknowledge that there are no simple patients. Holistic activities with concentrated work on the “hard parts” promote the acquisition of needed knowledge and skill with the opportunity to learn how to learn.17

Student ownership and responsibility

The clinical education experience belongs to the student, despite the fact that it occurs in the CI’s clinic. It involves patients to whom the CI has legal and ethical responsibilities. It requires the CI’s time, energy, and creativity. It is imperative, however, that the student accepts ownership and responsibility for the experience. Clinical education is not only an opportunity for a student to learn the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes of the profession, but also is the first experience in a lifelong pattern of learning and continual development as a physical therapist. Table 9–3 summarizes principles that enhance competence and encourage self-determination in actions. It is important that students assume responsibility for learning what they need to know and how to go about learning it.

Table 9–3 Principles that Dampen or Motivate Students to Enhance Competence and Encourage Self-Determination in Actions

| Dampeners | Motivators | |

|---|---|---|

| Focus of goal orientation | Judgment | Development and learning |

| Performance expectations | Low | High |

| Learning opportunities | Governed by rules and regulations Prescriptive, mandatory experiences | Self-directed Multiple opportunities with recommendations |

| Instructional strategies | Routine Extrinsic rewards and incentives | Challenging Encourage deep and rich thinking processes |

| Feedback/evaluation | Dominate and control behavior | Available but infrequent from external sources |

| Institutional/personal premiums | Emphasize conformity | Emphasize creativity, innovation, and alternative perspectives |

Adapted from Lewthwaite R, Burnfield JM, Tompson L, et al. Education and development principles. Presented at: Seventh National Physical Therapy Clinical Education Conference; April, 1995; Buffalo, NY.

Process of clinical learning

CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR: She’s doing fine. I don’t have any complaints. You know, she’s right where she should be. I don’t mean that she’s perfect, but time and more experience help. She just has the usual student problems. She asks questions. She fits in here, and she’ll be a good physical therapist someday.

KATIE: I don’t know. It’s not bad, but I’m not sure that I’m learning. I mean, I know I’m learning, but I think I could be doing more. I sort of feel like a junior therapist. I come in, treat my patients with some help, and go home.

Katie is participating in the third of four clinical education experiences. She performs adequately but seems stuck. She thinks that she isn’t learning as much as she is capable of, but she does not seem to know where to go from here. Consider steps the DCE might take, the CI’s responsibilities, and what Katie needs to do to continue the learning process. The American Physical Therapy Association Clinical Instructor Education and Credentialing Program provides pragmatic instruction with case examples for facilitating learning in the clinical environment.18

Bridging Theory with Practice

BECKY: I was doing okay until the patient threw me off track by giving the wrong answer to my question. I mean, she isn’t supposed to have pain in her shoulder all night long, unless she has cancer or something bad like that. I was pretty sure she had a frozen shoulder.

STUDENT: My CI is so smart. How did she learn all she knows? Yesterday a patient tried to refuse treatment, but she just didn’t take “no” for an answer. The patient ended up doing better during the treatment session than I had ever seen him do. Then, this morning, Mr. Jones said that he wasn’t up to physical therapy. She just said, “Okay, we’ll check back later.” An hour later, they called a code. I looked at his chart and everything. There was nothing to predict that. How did she know?

INARA: I evaluated my first patient yesterday. I had done parts of several exams with my CI, but this was the first in which I was responsible for the whole thing. My CI made suggestions, and I implemented them as I went along. It went pretty well. The patient will be back tomorrow, and I’m anxious to see how he’s doing. After I finished the note (with revisions), I thought I was done. But my CI asked me to go home and compare what I had done with the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. We’d used it at school, but I never thought about using it here in the clinic. Anyway, I had to find the practice pattern, and then I was surprised that it helped me think of things I hadn’t thought of. With this CI, there’s always more to learn … .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree