Chapter 3 Teaching and Learning In Academic Settings

A Practical Model for Teaching and Learning

Classroom Teaching with Large Groups

Strategies for Facilitating Collaborative Learning

Clinical Laboratory Teaching: Development and Assessment of Clinical Practice Skills

Clinical Laboratory Teaching: Integrating Doing, Thinking, and Reasoning

Clinical Laboratory Teaching: Assessment of Clinical Skills

Strategies for Facilitating Reflection and Problem Analysis

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe how the core components of a “practical model for teaching” apply to experience in teaching and learning.

2. Apply the key concepts from Shulman’s Table of Learning to the teaching and learning process. Discuss the design and implementation of effective lectures, including purposes, lecture planning, and lecture delivery with techniques for facilitating interactive lectures.

3. Describe strategies for facilitating the use of small group, collaborative learning, including the use of structured small group activities and peer teaching.

4. Justify the rationale that supports grading as a tool for learning and the pros and cons of various grading systems and written examination formats.

5. Apply the phases of learning psychomotor skills to teaching clinical laboratory skills and discuss how to enhance demonstrations of clinical skills and teach more complex psychomotor skills.

6. Outline the process for developing a clinical practical examination blueprint to assess psychomotor skills and reasoning and decision-making skills.

7. Identify and discuss teaching strategies for facilitating students’ meta-cognitive, reflection, and problem analysis abilities.

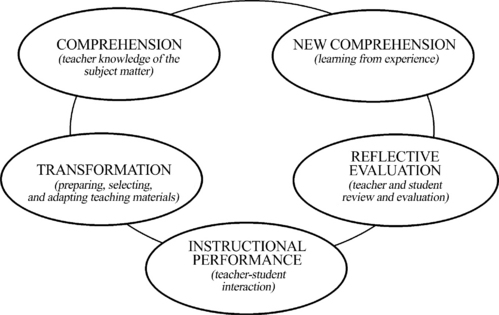

1. Content and knowledge that a teacher holds and must share with students,

2. Transformation (transforming what is known into material that can be taught to others),

3. Instruction (teaching performance), and

4. Reflective evaluation (learning from one’s teaching experience), which leads to

5. New comprehension or understanding as one learns from experience (Figure 3-1).1 The chapter then focuses on basic teaching and evaluation tools for large groups in the classroom, including lectures and strategies for facilitating collaborative learning, teaching and evaluation tools for clinical laboratory performance, strategies for facilitating reflection and problem analysis, and a brief overview of teaching technologies.

A practical model for teaching and learning

Knowledge of the subject matter

Good teachers have a thorough knowledge of the subject matter that allows them to display more self-confidence and creativity in teaching. Investigations of teachers also demonstrate that teachers not only have information in the area but also understand how the key concepts or ideas are connected, as well as the ways in which new knowledge is created and validated.1,2 Using the previous anecdote, remember that the instructor was nervous about having to cover measurement concepts and was unable to engage the students in any interaction during a lecture. The teacher ended up covering the material on the handout with little student interaction. Why did this happen? Perhaps the instructor, although very comfortable with teaching the clinical skills of measurement (i.e., goniometry and manual muscle testing), was much less certain of her or his knowledge of clinical measurement concepts; therefore, the instructor covered the content with little discussion. For example, in discussing the measurement concept of validity and manual muscle testing, a teacher with thorough knowledge of clinical measurement would move beyond the definition of validity to a discussion of the use of manual muscle testing for the assessment of muscle weakness. Use of muscle testing for assessing muscle strength raises a validity question.3 Research on teachers supports this example; when teachers do not know the subject matter well, they tend to focus more on content, whereas teachers who know their subject well teach not only the content but also the practical application of key concepts and the current controversies of what is known and not known about the subject.1,2,4

Transformation

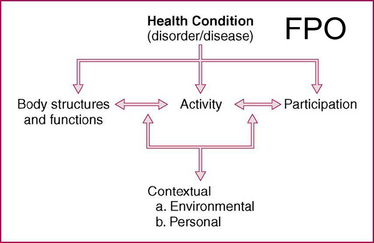

The transformation phase represents the teacher’s ability to “transform” the material so that students can understand. As teachers, we need to get the “inside out”— that is, we need to know what is going on inside the heads of our learners.5 There are teachers who are quite expert in certain subjects, yet they are dismal teachers. A second component of teaching is the teacher’s ability to do good “preactive teaching.” As detailed in Chapter 2, there is specific knowledge and skill involved in taking what is known and transforming it in preparation for teaching. First, one must review any instructional materials in light of what is known about the subject: Are there any errors? Have things changed? Has the thinking changed in this subject? A second step in transformation is thinking about how to go about presenting the content. What learning theories will you use and what type of objectives will you focus on? Will you use a clinical case, a focused small class activity, or visual aids? A final step is deciding how to tailor your understanding of the content to students’ understanding. Students are not likely to have the breadth and depth of knowledge that the instructor has. The critical issue is for the instructor to adapt what he or she knows and come up with examples or representations that fit the students’ present understandings of the content.5 In the anecdote of teaching clinical measurement, one may be discussing range-of-motion measures as they apply to physical impairment measures and challenge students that they will ultimately need to address any functional limitations the patient may have. In doing so, the teacher also assumes that the students remember the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) model that had been presented and discussed the previous week (Figure 3-2).6 The instructor quickly discovers that the students do not understand and therefore must backtrack, using the key model concepts and tying them in a simple and direct way to patient cases.

Instruction

Instruction is what is known as teaching, yet instruction is only the interactive phase or “performance” of teaching. It includes everything from pacing of the material, to classroom management, to asking and responding to questions. Many of the specific teaching tools discussed in this chapter are part of the instructional process. Active learning or learner engagement is frequently discussed as a key component of the instructional process.5,7,8 Students must be engaged in their learning in order to learn. Some general characteristics of and strategies for active learning have been suggested by Barkley7:

• Be clear on your learning goals.

• Focus on the learning that results from the activity as opposed to the activity itself.

• Be clear on what your role is as teacher.

• Remember that teaching is not “telling.”

• Help learners develop learning strategies such as linking concepts together, applying concepts to problems, or analyzing problems.

• Use strategies that will help learners transfer what they know to what they are learning.

• Teach for retention (here, an emotional connection is helpful, along with having the information make sense to the student and have meaning, such as a clinical case or context).

Reflective evaluation and new comprehension

This last component of the practical model for teaching is the ongoing process of learning from experience. This process of reviewing, reconstructing, and critically analyzing one’s own performance and the class’s performance is lifelong learning, a process that is central to teaching. For example, in the anecdote at the beginning of this chapter, the teacher found that after he or she presented the ICF model, followed by the patient clinical measurement data, the class looked perplexed and did not respond to questions. What could be done? The teacher could interrupt the class and admit that there appeared to be some confusion. The teacher might then begin to go through the model again by asking students to provide their understanding of the concepts and the clinical application. The teacher could clarify each concept while going through the model with the class. This is an example of reflection. In the reflection process, a problem arises with some uncertainty, so one engages in a process of thinking critically about what is going on and devising alternative solution strategies. The first step involves seeing the problem. In this case, the instructor stops the class because he or she recognizes that students are confused. Then the group reviews the ICF model, which can lead to a revised or new understanding with the instructor’s guidance. The reflective process in this example is likely to lead to new understandings or comprehensions for students and teacher (see Figure 3-1). The last two sections of this chapter emphasize teaching techniques used to facilitate collaboration and reflection in the classroom.

Classroom teaching with large groups

Lectures

You need to remember that the lecture method is not just telling but involves carefully planning for organization and delivery. There is an old saying that lectures are a method of transferring the notes of the teacher to the notes of a student without passing through the heads of either.9,10

The lecture method of teaching was a prominent method for disseminating information before the invention of mass print in the 1600s. In these lectures, the instructor would talk, while the students wrote everything down—in effect, creating their own “texts.” Why is it that the lecture remains such a significant part of our teaching repertoire in the midst of ready access to information through many sources?9,11

What Purposes Do Lectures Serve?

Lectures are often used to transmit a lot of information efficiently to large groups of students. McKeachie summarizes the skills of a good lecturer, saying “[e]ffective lecturers combine the talents of scholar, writer, producer, comedian, showman, and teacher in ways that contribute to student learning.”9 Research comparing the lecture to other forms of teaching demonstrates that the lecture is as effective as other methods for teaching knowledge. In addition to the cognitive component, lectures can also motivate. A skilled lecturer can stimulate interest, challenge students to seek more information, and communicate passion and enthusiasm for the subject matter. Lectures can also be used as an efficient method to consolidate and integrate information from a number of different printed sources. Lecture material can be specifically adapted or tailored to the class, and difficult concepts can be clarified in lecture. Finally, lectures can set the stage for discussion or other learning activities.9

What Makes an Effective Lecture?

Planning

Teachers might plan a lecture as they approach writing a paper by thinking about the overall organization, the introduction, body, and conclusion. Good overall questions to start with when planning a lecture, in contrast to “covering the subject matter,” are (1) What do you really want students to remember from this lecture over time? (2) How should students process the information? (3) Are you trying to be a conclusion-oriented lecturer, or is your aim to assist students to learn and think through a cognitive activity? (Review your preactive teaching grid [see Figure 2–1].)

One of the major concerns is keeping students’ attention. One study reports that students recall 70% of the material covered in the first 10 minutes of class and only 20% of material covered in the last 10 minutes.12 This finding about the serial placement of material remains constant. We remember best what comes first and second best what comes last and remember the least what comes in the middle.7 How does the instructor capture the students’ attention? One effective strategy is to announce that the information presented will be tested; however, there are also many other ways to stimulate students’ thinking and actively involve them in learning.

Introduction

An effective introduction focuses and engages the students and outlines the specific topics that will be covered and the order in which the topics will be discussed. The introduction should also identify the gap between the students’ existing cognitive knowledge and the topic, or it should raise questions. Pre-questions can be used to focus students toward the intent of the lecture. For example, imagine that the topic is an introduction to the role of culture in professional-patient interactions. One may begin the lecture by standing in the back of the room (not the front) to talk to the class. The teacher may ask the class to share observations about the traditional role of the teacher and then proceed to ask questions about students’ meanings of classroom behavior—that is, the culture of the classroom. Another useful technique is to begin with a story or a case that highlights the relevance and importance of the lecture subject matter.9

Body

The body of the lecture should fit with the students’ ability to process information. Perhaps the most common error of the novice teaching is to try to put too much information into the lecture. This occurs when the teacher overestimates the students’ ability to grasp the information and see the relationship between concepts and applications. Russell et al.12 demonstrated that increasing the density of a lecture reduces the students’ retention of basic information. Often, trying to present too much information is the result of inadequate preparation in which the teacher has not clearly identified the key concepts.

The lecture should not be written out verbatim, but an outline can be very effective in guiding the body of the lecture. Color coding your notes can also be an effective procedural strategy. The use of graphic representations, computer flow charts, models or media clips can provide the class with a representation of the structure of the material presented. The instructor can also place cues in the lecture outline margins or notes that include learning strategies to be used along the way (e.g., the use of overheads, stimulating questions, different types of explanations, or brief dyad discussions among students).9,11

A single class usually represents a diverse group of learners. Some students may do better with a deductive process-that is, going from a sequence of generalizations to specific application—whereas other students may do better with a more inductive process—that is, moving from the specifics to the general concepts. The use of an outline and a visual structure provides cues for both groups.13 An easy rule of thumb for a great lecture is a simple framework and lots of examples. Additional tips for facilitating student comprehension can be found in Box 3-1.9

Box 3-1 Tips for Facilitating Student Comprehension

• Develop the idea or concept, then give examples. Reiterate your initial point.

• Pauses give students time to think—give periodic summaries in your lecture. You do not have to cover everything.

• Check for understanding. This is not just the standard, “Any questions?” If you want to check for understanding, give students a minute to write down a question. They can compare with their neighbor, and then you will get some questions from the class.

Conclusion

The conclusion is a time to summarize the important points of the lecture by going back over the outline or key graphics. The teacher may also use this as an opportunity to have students summarize the material orally or in writing. Other strategies include having the students do a 3-minute writing exercise summarizing the major points of the lecture, or looking at student lecture notes to see what they are writing to determine whether they grasped key concepts. These methods provide additional information about the students’ understandings of the lecture.9,13

Lecture Delivery: How Can You Maintain Attention?

Earlier in this chapter, we stated that instruction can be thought of as performance, and lecture delivery provides one of the most obvious chances to perform. Passion and enthusiasm for the subject matter are key aspects of any lecture. Although one of the most common strategies for getting students to pay attention is to say this will be on the test, there are also other strategies the teacher can use. The teacher is a powerful role model in front of the class and represents a thoughtful scholar to the students. Tips for improving lecture presentation can be found in Box 3-2.9,10

Box 3-2 Tips for Improving Lecture Presentation

• Create movement. Change your position in the room. Do not remain anchored at the podium.

• Use visuals. Use various visual teaching tools (e.g., overheads, the blackboard, charts, graphs). These visuals are particularly good for highlighting key points. Videotapes can be powerful tools for illustrating examples from the real world in the clinic or community.

• Pay attention to the effect of the voice. The voice can vary in terms of volume, rate, and tone. If your voice is not loud enough for the class to hear, a microphone may be necessary. Beware of avoiding a monotone delivery. Voice is one of the key ingredients for communicating enthusiasm to the students. The use of audiotape or videotape can be a helpful feedback mechanism for assessing how you use your voice.

• Pay attention to body language. In addition to the voice, teachers also communicate with students through nonverbal language. Be aware of nervous habits, such as playing with the pointer, jingling change, or any other persistent movement of the hands. Use body language to communicate points of emphasis and enthusiasm.

• Pace the delivery and clarify the material. As stated earlier, two common elements of excellent lectures are a simple plan with a structure and the use of numerous examples.9 The structure of the lecture provides the foundation for pacing the delivery of the material. Observe the audience to see whether they are keeping up with note taking, are confused, or need more time for questions. Remember that attention in lectures declines after the first 20 minutes, so vary your activities. A second consideration is how to go about clarifying difficult concepts. In the previous section on transformation, we advocated that teachers are responsible for transforming ideas to assist learning. Ideas can be represented through analogies or metaphors. For example, performing a grade 1 mobilization movement can be described as having “a fly do deep knee bends” to overillustrate how small the movement it is. A metaphor can be useful for having students think expansively and creatively. For example, which metaphor best describes the work of a physical therapist or physical therapist assistant: teacher, gardener, business executive, or healer?

Perhaps the greatest advantage of the lecture is that it is economical, particularly when the teacher has lots of students and little time. The strongest disadvantages are the passive role of the students and the lack of student engagement in higher-order cognitive objectives (e.g., analysis, evaluation). One quick classroom assessment technique for determining whether students are attending to and grasping the lecture materials is called the punctuated lecture14:

• Listen: Students listen to the teacher’s presentation.

• Stop: Teacher stops the presentation.

• Reflect: Students are asked to reflect on what they were doing while they were listening and how their behaviors enhanced or hindered their ability to listen and understand the material.

• Write: Students then write down their reflections (anonymously).

The use of personal response systems (computer-input devices) or clickers allows the teacher to interject questions or other activities and have students respond through the use of the handheld device. Refer to Chapter 4 for more on the role of technology.

Another area for facilitating students’ attention during the lecture is teaching students to be better listeners. This can be done by posing questions that can help them focus. What were the two most important points in this reading? You could have students listen to part of your lecture without taking notes and then write a brief summary or summarize the main points of the lecture.9

Should Students Take Notes during Your Lecture?

We know that note taking is an aid to your working or short-term memory. The critical component of note taking is that students need to be able to “chunk” or integrate the information. If they are madly taking notes trying to keep up, they run the risk of not integrating the information. Research demonstrates that for students with less background knowledge, note taking may limit their capacity for listening. Should a teacher distribute the lecture notes beforehand? In a recent study, students who received class notes before a lecture compared with after the lecture actually attended class more regularly and participated more in class. There is also research that supports giving students an outline that they must fill in.15

The interactive lecture: role of discussion and questioning in large group settings

Initiating the Class Discussion

• Start with a question. A discussion usually starts with a question. This question could be focused on a common experience (e.g., a reaction to a visual, a videotape, or a story).

• Lead with controversy or a debate. With this strategy, the class could be divided into two or more large groups and be given the task of developing a position.

• Have students brainstorm. When students brainstorm what they know about the topic, the teacher can use these ideas to build a framework consistent with the students’ understandings and discuss with the group any misconceptions.7,10

• Use the Socratic method of dialogue or discussion. This approach has been used extensively in the education of lawyers. In this method, teachers focus on teaching from a known case to general principles, thus teaching students to think like a lawyer. The general questioning strategy is to use a known case to formulate general principles, and then to apply these principles to new cases; for example, you might begin by discussing the following with students9:

Common Discussion Problems

The two most common discussion problems are students who talk too much or too little. There are a number of reasons why students may be silent in the classroom (e.g., fear of looking stupid, prior bad experiences such as being mocked or berated, or even shyness). What can be done about students who do not talk during discussion? A supportive classroom environment is a key element. It involves more than encourages students to participate. To have a supportive classroom environment, the teacher must create an emotional and intellectual climate supportive of risk taking. Suggestions for facilitating a supportive classroom environment can be found in Box 3-3.7,9,13

Box 3-3 Tips for Facilitating a Supportive Classroom Environment

• Demonstrate a strong interest in students as individuals and be sensitive to subtle messages they give about the material or presentation.

• Respond to students’ feelings about class assignments and be willing to listen.

• Encourage and invite students’ questions and express interest in hearing their personal viewpoints. Consider having students write down their questions first, then ask them to share with the class.

• Demonstrate interest in the importance of students’ understanding of the material.

• Encourage students to be creative and independent in reacting to the material. Begin by asking students to share their perceptions or ideas about general questions that do not have a right or wrong answer.

• If there is an argument or conflicting views in a discussion, turn this into an assignment for continued investigation with library work.

• If students are disputing what you know, give yourself time to think by listing the different perspectives on the board.

• Pay attention to the physical environment of the classroom. Even though you may be lecturing, you still want the physical environment to encourage active learning. For example, in traditional classrooms and auditorium-style classrooms where most lectures take place, think about having students sit so that they can easily participate in quick interactions in twos or threes as learning groups.7

What about the student who talks too much and responds to every question? McKeachie9 suggests the following options for large groups:

• Ask the class if they would like the participation more evenly distributed.

• Audiotape a discussion and play it back for class analysis on how to improve the discussion.

• Assign class observers who observe participation and report to the class.

• Use a small group structure and assign roles for group members.

Questioning

One simple model classifies questions under three types: (1) concrete, (2) abstract, and (3) creative.9 Concrete questions generally focus on a recall of facts, literal meaning, and simple ideas. These are the “who, what, where, and when” questions. Abstract questions have students generalize, classify, or reason to a conclusion about the facts presented. These are the “how” and “why” questions. Creative questions ask students to reorganize concepts into a new pattern that may require abstract and concrete thinking. The teacher may ask, “What would happen if?” or “How else could you go about?”

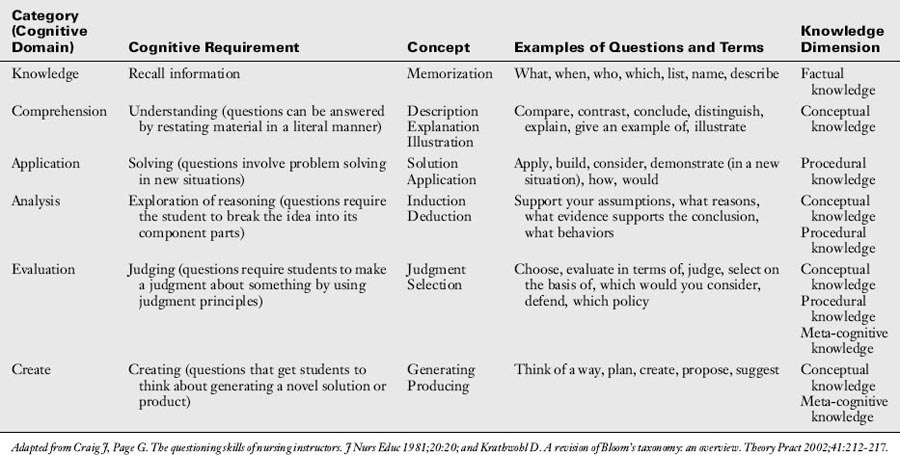

A helpful strategy is to think about the kinds of questions you would ask across the categories in the cognitive domain. In addition, you can include a column that identifies the knowledge dimension you are targeting (Table 3-1).16,17

Questioning Techniques

In addition to being aware of the type of question being asked, a teacher should attend to questioning technique or performance in the classroom (Box 3-4).9,11

Box 3-4 Recommendations for Effective Questioning Techniques

• Use open-ended, not closed-ended (i.e., questions that can be answered with “yes” or “no”), questions.

• Plan ahead to have key questions that will provide structure.

• Avoid combining too many concepts or ideas and phrasing an ambiguous question.

• Ask your questions logically and sequentially.

• Use different levels of questions, going from simple to more complex, or higher-order, questions.

• Allow adequate thinking time for students—in other words, keep quiet. Research has shown that most teachers allow less than 1 second of silence before asking another question or reemphasizing, and that when teachers wait 3 to 5 seconds, the number and length of appropriate responses increases.17

• Follow-up with student responses by making a reflective statement or using deliberative silence.

• Try to ask and use types of questions that are aimed at broad student participation. For example, after a response, ask for additions to the response.

Strategies for facilitating collaborative learning

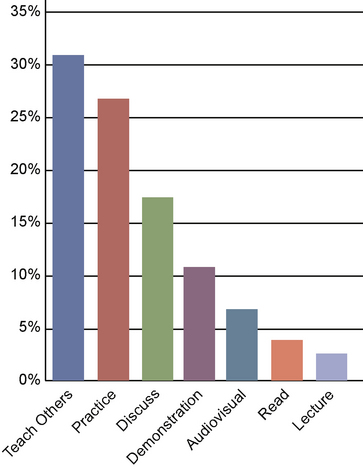

The best answer to the question, “What is the most effective method of teaching?” is that it depends on the goal, the student, the content, and the teacher. But the next best answer is, “Students teaching other students.”9 The retention rate for learning experiences and teaching methods that focus on learner engagement are impressive (Figure 3-3).

Small groups process: why group work?

Group work is an effective teaching and learning strategy for achieving intellectual goals (e.g., conceptual learning, creative problem solving) and social goals (e.g., oral communication, decision making, conflict management). Working in groups is part of many professional workplace activities.7,18 Two primary types of learning that lead to effective group work are collaboration and cooperative learning. Although not as much research on collaborative learning has been done in higher education, the findings from primary and secondary school research are relevant.7,18 One of the most consistent findings is that students learn better through noncompetitive, collaborative group work than in classrooms that are highly individualized and competitive. A second element supporting group work is related to our understanding of knowledge. All knowledge, including scientific knowledge, has an element of “social construction” (i.e., knowledge includes the shared understandings within the group or discipline). Students need to experience that knowledge is not transferred from one person’s head to another but rather is a consensus among members of a community of knowledgeable peers; it is dynamic understandings among people.

Learning in small groups provides the following19:

• A collective learning context

• Increased tolerance for complexity and uncertainty

• Opportunity to explore a diversity of views

• Development of learners’ skills of giving and receiving feedback

Preparation for Small Group Work

Students need to be prepared for successful group work. The following are two key concepts central to good small groupwork18:

1. Learning to be responsive to the needs of the group. Responsiveness to the needs of the group is a skill required for any cooperative task. Awareness of this skill can be facilitated through small group game activities, such as “broken circles,” in which the group must cooperate to solve the group problem (see Appendix 3-A).20

2. Developing a norm of cooperation and working toward equal participation. Having students learn about working toward equal participation is another important norm for small groups, whether the group’s task is discussion, decision making, or creative problem solving. Only when students believe that everyone in the group should have a say can any future problems of dominance be handled. Students need to appreciate that group leadership is a function shared between group members.7,18 A small group exercise called Epstein’s four-stage rocket21 is a good preparatory exercise for facilitating small group cooperative behaviors (see Appendix 3-B).

After students have gone through some initial group training, group work can be used as a teaching strategy. The following are basic ground rules for using small groups18:

• A group size of five to seven is optimal. Larger groups may be used when the task is so large that it needs to be subdivided.

• Groups should be diverse in terms of gender, academic achievement, and any other status characteristics that could influence group interaction. Allowing students to choose their own groups and work with their friends is usually not a good idea.

• The teacher must delegate authority and let go. The teacher is the direct supervisor who defines the task and suggests how the group might go about accomplishing the task, but the teacher is not in charge.

• If the overall goal is conceptual learning, then the learning task should require conceptual thinking rather than application of technique or information recall.

• The group must have the necessary resources to complete the tasks or assignments.

Group Expert Technique

The group expert technique is an extremely powerful tool that builds confidence and collegiality among group members and can cover several example cases. The technique involves two divisions of the class into small groups (Table 3-2). In the first division, each small group is given a different task (e.g., different patient cases to analyze). At this time, the teacher circulates around the class to make sure each group is on the right track. Each individual in the group must be an expert on solving the case because the class is then divided again, mixing representatives from each of the patient case groups. In this second division, each group member is an expert on a particular patient case. The task for the second group division is to discuss each of the patient cases with the resident expert available to facilitate the discussion. This small group strategy provides the class with a variety of patient problems to discuss in a short amount of time and gives each student equal status as a group expert for one case.22

Table 3-2 Steps Involved in Implementing the Small Group Expert Technique

| Step | Process |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Initial Assignment | Each student is given a handout with a number and letter assignment (e.g., 1A, 1B, 1 C, 1D, 1E, 2A, 2B, 2 C, 2D, 2E). |

| Step 2: First Group Division | Class is divided according to numbers. Each group is given a patient case to analyze. |

| Step 3: Teacher Checks Out | Teacher circulates around to all groups to make sure each group has analyzed case correctly. |

| Step 4: Second Division of Groups | Class now divides a second time according to the letter assigned. This means each of the groups will have representation from each of the patient problems. |

| Step 5: Group Expert Discussion | All groups discuss each of the patient problems. Every group will have a resident expert (a member from the original group) who can facilitate the discussion. |

Data from Cohen E. Designing Groupwork. New York: Teachers College Press, 1986.

Seminars

The seminar is another small group teaching method usually associated with graduate study. The seminar also can be used in undergraduate and professional education after students master some content. The purpose of a seminar goes beyond discussion of an important topic and includes analysis, critique, and application of a topic. A seminar is not a class with small enrollment, nor is it an undirected or unfocused discussion of a topic. A seminar is a guided discussion in which students take the intellectual initiative.9,13 Using seminars as a teaching method requires prior planning, explicit guidelines linked to objectives, and a clear structure for the students (Box 3-5).

Box 3-5 Ideas for Structuring a Seminar

• Progress from teacher-led to student-led seminars.

• Assign topics or allow students to select from a list of suggested topics.

• Give responsibility for resources to students (e.g., a bibliography and readings).

• Use guidelines for presentation format (e.g., use of audiovisuals, responsibility for facilitating discussion with entire seminar group).

Tutorials

A small group tutorial is a specific application of group work. In recent years, several of the health professions have begun advocating the central importance of problem-based learning, using a small-group tutorial as the teaching strategy aimed at solving patient cases. Essentially, each small group of generally no more than 10 students and one facilitator is a learning group. A faculty tutor assists students in moving from teacher-centered to student-centered learning.10,19 The tutor is responsible for guiding the process of learning at the meta-cognitive level; that is, the tutor helps students in thinking about their thinking as they work through the learning process.10,19,23 This type of learning group can be a very effective means for students to practice skills they will need as professionals. Using learning groups may require changes in faculty’s teaching strategies as well as major or minor curriculum revisions. Tuckman’s four stages of group development can be a helpful tool in working with small groups. (Table 3-3).

Table 3-3 Tuckman’s Four Stages of Group Development

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Forming | Information is exchanged; group members’ strengths and weaknesses are exchanged. |

| Storming | Conflict, dissatisfaction, and competition; can have interpersonal hostility; trust may be formed; group members may depart to another group. |

| Norming | Attempts are made to function by setting up rules and norms for behavior; clarity for roles and responsibilities; forming group identity. |

| Performing | Requires successful completion of the first three stages; perform at optimal level; focus on task as well as how everyone works; disagreements are accommodated within the group. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree