Synovial Diseases of the Hip

John Clohisy

Key Points

Introduction

The hip is a synovial joint that functions as the primary link between the trunk and lower limbs, and provides bodily support and mobility in the upright position. Synovial joints are differentiated from cartilaginous and fibrous joints by the existence of capsules surrounding the articulating surfaces of the joint and the presence of lubricating synovial fluid within the capsule. The synovium is a thin, specialized tissue that lines noncartilaginous spaces within the joints (e.g., hips, knees, elbows). This tissue is a few cell layers thick and plays a major role in regulating the fluid and cellular environment within the joint.1 A highly vascular capillary system within the synovium provides joint lubricating fluid containing hyaluronan and lubricin. The synovium mediates molecular and cellular changes within the joint and protects the joint from physiologic and biomechanical stresses. Additionally, the synovium provides macrophage access to the joint.2 Activated macrophages perform several immunologic functions within the joint space and are important mediators of both joint homeostasis and certain disease states.

Primary disorders of hip synovium are relatively rare, even in a high-volume hip practice. The most common disorders include synovial chondromatosis and pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). Both of these conditions are benign tumors of synovial origin. Successful orthopedic management of these conditions is dependent on a timely diagnosis and successful removal of the primary tumor. Failed treatment and recurrent disease can be associated with articular cartilage degeneration and secondary osteoarthritis. This chapter will review the important concepts associated with diagnosing and treating these benign synovial disorders.

Synovial Chondromatosis

Overview

Synovial chondromatosis is a benign, monoarticular arthopathy that infrequently involves the hip. In fact, hips account for only 10% of diagnosed cases. Disease involving knees (50% to 65% of cases) and elbows (20% to 25%) is far more common. Males are affected twice as often as females. The disease process begins with metaplastic differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the synovial membrane of the joint. These cells mature into chondroblasts and form small nodules of cartilage in intimal layers of the synovial membrane. These nodules subsequently enlarge and detach to lie within the joint space, resulting in the formation of multiple intracapsular and extracapsular loose bodies.3 These loose bodies continue to grow in diameter via multiplying chondrocytes and may calcify in their central zones, leading to the term osteochondromatosis (Fig. 36-1).

Figure 36-1 A, Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the left hip in a 63-year-old male. The radiograph shows numerous calcific densities within the hip joint. They surround the femoral neck and are seen within the acetabular notch. The pattern of calcification is typical for cartilage, and the lesions represent osteocartilaginous bodies within the joint and synovium. B, T1-weighted coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows the thickened synovium surrounding the head and within the acetabular notch. The pattern is consistent with a primary intra-articular process. Together with the plain film, this represents synovial chondromatosis.

Villacin4 described two forms of synovial chondromatosis. The primary form of synovial chondromatosis is characterized by numerous small, round loose bodies that are uniform in size. It is not precipitated by any identifiable joint pathology and likely occurs secondary to metaplasia. Lesions are often aggressive and are associated with a high incidence of recurrence. Conversely, the secondary form is characterized by fewer, larger, more variably sized cartilaginous masses. This form is more likely to occur in the setting of preexistent osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteonecrosis, osteochondritis dissecans, neuropathic osteoarthopathy, tuberculosis, or osteochondral fracture. The underlying disease process generates chondral fragments that implant into synovium, inducing metaplastic cartilage formation.

Milgram further described synovial chondromatosis as a self-limited intrasynovial process that occurs in three phases: early, transitional, and late.5 In the early phase, only active intrasynovial disease is present, with no loose bodies. The transitional phase includes both active intrasynovial proliferation and free loose bodies. The late phase shows multiple free osteochondral bodies extruded in the joint space but no demonstrable intrasynovial disease. These phases become important in clinical decision making in determining the necessity of performing synovectomy to treat symptoms and prevent disease recurrence.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Synovial chondromatosis of the hip can be challenging to diagnose. In contrast to disease presentation in other joints (knees and elbows), signs of synovial thickening, crepitus, and palpable loose bodies usually are absent. Synovial chondromatosis of the hip most commonly presents with nonspecific and insidious symptoms such as pain, stiffness, and limitation of motion. Further complicating the diagnosis are plain radiographic images, which are normal in more than 50% of cases because tumorous lesions often are noncalcified and radiographically lucent. When clinical suspicion prompts further imaging, computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies usually identify chondral and/or osteochondral bodies in the joint. On CT, loose bodies form a soft tissue mass of water density that elevates the joint capsule. MRI may show three distinct patterns as described by Kramer and associates.6 Pattern A (12%) is described as a lobulated homogeneous intra-articular signal isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Pattern B (80%) incorporates the features of pattern A with addition of signal void foci on all pulse sequences. Last, pattern C (8%) has features of patterns A and B plus foci of lesions with peripheral low signal surrounding a central fatlike signal. The diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis can be supplemented by magnetic resonance arthrography with gadolinium contrast, which shows multiple filling defects in the joint. Biopsy remains the gold standard in diagnosis. Histopathology shows a thickened synovium with loose bodies adherent to the synovium or floating freely in the joint.

Treatment

Recommended management of synovial chondromatosis consists of surgical removal of loose bodies combined with a partial or complete synovectomy.7,8 Total excision of loose bodies is essential to optimize symptom relief and to theoretically protect the joint from additional articular cartilage damage. Historically, loose body removal was thought to be as efficacious as synovectomy for prevention of recurrence, but later studies showed a statistically lower recurrence rate with synovectomy.7,8 Nevertheless, recurrence rates from 0% to 23% have been reported after synovectomy.3,7,8

The most established treatment remains complete synovectomy via surgical dislocation of the femoral head. Full exposure of the hip is achieved only by surgical dislocation. Postel and colleagues showed in 23 patients treated with open arthrotomy (11 hips left in situ and 12 dislocated) that recurrence rate and prevention of secondary arthrosis were more favorable with dislocation.9 Lim and co-workers showed in 21 patients undergoing open arthrotomy and complete synovectomy (13 hips left in situ and 8 dislocated) that recurrence rates increased in patients treated without surgical dislocation.10 The increase in recurrence rates was believed to stem from the persistence of pathologic synovium in the depth of the acetabular fossa.

Previously, surgical dislocation carried an unknown risk of avascular necrosis (AVN); it now is safe and carries minimal risk of AVN. Specifically, the approach introduced by Ganz and associates preserves the terminal branches of the medial circumflex femoral artery and has a very low risk of osteonecrosis.11 Schoeniger and colleagues used the Ganz approach to avoid risk of osteonecrosis in eight patients with monoarticular synovial chondromatosis of the hip.8 They performed joint débridement and a modified total synovectomy via surgical hip dislocation with a trochanteric flip osteotomy. After follow-up for at least 4 years (mean, 6.5 years), no patients had recurrence of disease. Furthermore, no patients developed complications secondary to osteonecrosis of the femoral head.

Arthroscopic management of synovial chondromatosis has become more acceptable for early management of the disease. Boyer and co-workers12 showed that hip arthroscopy provided good or excellent outcomes in more than half of cases. Of 111 patients, 63 reported excellent (>75% subjective improvement) or good (>50% subjective improvement) outcomes. However, 38% of patients failed arthroscopic treatment and required open surgery. This high rate of treatment failure suggests that arthroscopic treatment has limitations in achieving complete tumor removal. The major advantage of an arthroscopic procedure is less invasive exposure of the hip joint performed without dislocation and/or trochanteric osteotomy. Nevertheless, these advantages are tempered by more restricted access to the joint and limitations with loose body removal and synovectomy. Although open procedures are better for preventing recurrence, the role of arthroscopic surgery needs to be better defined. Open procedures seem more appropriate for nonfocal disease patterns (Fig. 36-2), and arthroscopy may have a role in focal or less extensive disease patterns.

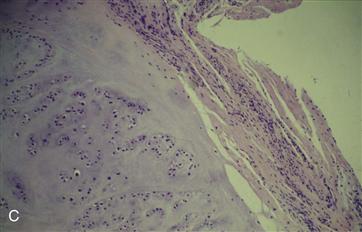

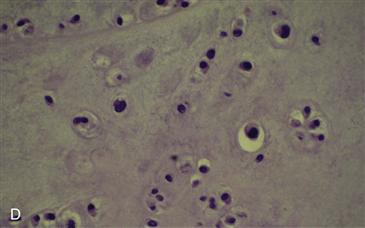

Figure 36-2 A, Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the right hip in a 61-year-old male with hip pain and stiffness. A large osteochondral body is inferior to the femoral neck, and numerous smaller osteocartilaginous lesions can be seen surrounding the femoral neck and the inferior acetabulum. B, Gross photograph of numerous osteocartilaginous loose bodies that were removed from within the joint and those embedded within the synovium. C, Low-power photomicrograph shows the edge of one of the osteochondral bodies with a benign pattern of cartilage proliferation. D, High-power photomicrograph illustrating benign chondrocytes with no nuclear atypia and abundant cartilaginous matrix.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree